Schindler's List

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pulp Fiction © Jami Bernard the a List: the National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films, 2002

Pulp Fiction © Jami Bernard The A List: The National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films, 2002 When Quentin Tarantino traveled for the first time to Amsterdam and Paris, flush with the critical success of “Reservoir Dogs” and still piecing together the quilt of “Pulp Fiction,” he was tickled by the absence of any Quarter Pounders with Cheese on the European culinary scene, a casualty of the metric system. It was just the kind of thing that comes up among friends who are stoned or killing Harvey Keitel (left) and Quentin Tarantino attempt to resolve “The Bonnie Situation.” time. Later, when every nook and cranny Courtesy Library of Congress of “Pulp Fiction” had become quoted and quantified, this minor burger observation entered pop (something a new generation certainly related to through culture with a flourish as part of what fans call the video games, which are similarly structured). Travolta “Tarantinoverse.” gets to stare down Willis (whom he dismisses as “Punchy”), something that could only happen in a movie With its interlocking story structure, looping time frame, directed by an ardent fan of “Welcome Back Kotter.” In and electric jolts, “Pulp Fiction” uses the grammar of film each grouping, the alpha male is soon determined, and to explore the amusement park of the Tarantinoverse, a the scene involves appeasing him. (In the segment called stylized merging of the mundane with the unthinkable, “The Bonnie Situation,” for example, even the big crime all set in a 1970s time warp. Tarantino is the first of a boss is so inexplicably afraid of upsetting Bonnie, a night slacker generation to be idolized and deconstructed as nurse, that he sends in his top guy, played by Harvey Kei- much for his attitude, quirks, and knowledge of pop- tel, to keep from getting on her bad side.) culture arcana as for his output, which as of this writing has been Jack-Rabbit slim. -

Download the 2021 Milwaukee Film Festival Program Guide Here!

#MFF2021 Hello Film Fans! It’s appropriate that, for our first-ever spring Milwaukee Film Festival, the significance of the season is stronger than it’s ever been. Our world is opening up, and our thoughts are once again wandering beyond the confines of anxiety and isolation that have defined the past 14 months. Though we’re not yet to the point of safely welcoming crowds to a packed house at the Oriental Theatre, we can envision a time in the not-too-distant future when that will be happening again. In the meantime, we are incredibly pleased to bring you the 13th annual Milwaukee Film Festival, presented by Associated Bank. Though we’re still virtual, the stories shared through this year’s films have real impact. There’s something for everyone – compelling documentaries, soaring features, quirky shorts, stories from distant shores, and local treasures. When you look at our films, it’s amazing to see how the film industry – and Milwaukee Film itself – have endured through a year when nearly everything we took to be normal was suddenly out of reach. Both filmmaking and film viewing are community endeavors that compel us to gather in person. There was a time when we briefly questioned whether we’d have enough content to offer our film festivals during a pandemic. But that hasn’t been the case at all, and it’s a testament to the unstoppable nature of the creative spirit. On the cover, our bright and beautiful Festival artwork shines like the light at the end of a tunnel. -

Does Wikipedia Information Help Netflix Predictions?

2008 Seventh International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications Does Wikipedia Information Help Netflix Predictions? John Lees-Miller, Fraser Anderson, Bret Hoehn, Russell Greiner University of Alberta Department of Computing Science {leesmill, frasera, hoehn, greiner}@cs.ualberta.ca Abstract data, but it must be free for commercial use. Unfortunately, this eliminates IMDb, even though this is known to be use- We explore several ways to estimate movie similarity ful for Netflix predictions [14]. Fortunately, this does not from the free encyclopedia Wikipedia with the goal of im- prevent us from using movie information from the free en- proving our predictions for the Netflix Prize. Our system cyclopedia Wikipedia 1. first uses the content and hyperlink structure of Wikipedia Data sources such as IMDb and Yahoo! Movies are articles to identify similarities between movies. We then highly structured, making it easy to find salient movie fea- predict a user’s unknown ratings by using these similarities tures. As Wikipedia articles are much less structured, it is in conjunction with the user’s known ratings to initialize more difficult to extract useful information from them. Our matrix factorization and k-Nearest Neighbours algorithms. approach is as follows. First, we identify the Wikipedia ar- We blend these results with existing ratings-based predic- ticles corresponding to the Netflix Prize movies (Section 2). tors. Finally, we discuss our empirical results, which sug- We then estimate movie similarity by computing article gest that external Wikipedia data does not significantly im- similarity based on both article content (term and document prove the overall prediction accuracy. frequency of words in the article text; Section 3) and hyper- link structure (especially shared links; Section 4). -

Nomadland-Screenplay.Pdf

NOMADLAND Written by Chloé Zhao Based on the book by Jessica Bruder January 12, 2019 Music. Title sequence: Archival black and white photos of Empire -- One of America’s longest running mine and company towns in the Black Rock desert of Northern Nevada. The factory. Workers. Meetings in board rooms. White piles of gypsum against black mountains. Families playing at the pool. People leaving church. Grand opening of a grocery store. Faces smiling. Children playing in the yard of a grammar school. A community flourishing. Proud townsfolk posing outside the factory. Young lovers getting married. A man mowing his lawn. A young woman standing in front of her house, looking at the camera. She is FERN. Title sequence ends. The sound of heavy wind... EXT. EMPIRE - STORAGE - EVENING The metal storage door rises, revealing Fern, now in her sixties, and the snowy landscape behind her. She digs through dusty boxes and trunks, scanning for lucky items to bring with her. A stack of plates with autumn leaf patterns and a rusty camping lamp make the cut. She loads them into “Vanguard”, a white Ford cargo van, rusty and muddy, parked in the snow. Fern keeps searching when she pulls out a man’s blue work coat that’s too big for her. She holds it to her face like an old friend and breathes it in. Holding back tears. Later, she pays storage fee to GAY, seventies, the storage owner and an old-timer. They give each other a hug. GAY You take care of yourself out there. EXT. ROAD - NORTHERN NEVADA - EVENING Vanguard travels across an endless, frostbitten landscape. -

93Rd Oscars® Nominations Announced

MEDIA CONTACT Academy Publicity [email protected] March 15, 2021 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Note: Nominations press kit available here 93RD OSCARS® NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED THE OSCARS SET TO AIR LIVE, APRIL 25, 2021, ON ABC LOS ANGELES, CA – Actor-producer Priyanka Chopra Jonas and singer, songwriter and actor Nick Jonas announced the 93rd Oscars® nominations today (March 15), live from London, via a global live stream on Oscar.com, Oscars.org, the Academy’s digital platforms, an international satellite feed and broadcast media. Chopra Jonas and Jonas announced the nominees in 23 categories at 5:19 a.m. PT. For a complete list of nominees, visit the official Oscars website, www.oscar.com. Academy members from each of the 17 branches vote to determine the nominees in their respective categories – actors nominate actors, film editors nominate film editors, etc. In the Animated Feature Film and International Feature Film categories, nominees are selected by a vote of multi-branch screening committees. All voting members are eligible to select the Best Picture nominees. Active members of the Academy are eligible to vote for the winners in all 23 categories beginning Thursday, April 15, through Tuesday, April 20. To access the complete nominations press kit, visit www.oscars.org/press/press-kits. The 93rd Oscars will be held on Sunday, April 25, 2021, at Union Station Los Angeles and the Dolby® Theatre at Hollywood & Highland Center® in Hollywood, and will be televised live on ABC at 8 p.m. ET/5 p.m. PT. The Oscars also will be televised live in more than 225 countries and territories worldwide. -

Library of the Yazoo Library Association| 310 N

Gordon Lawrence Contents: • Newspaper article • Brief encyclopedia sumnnarv Location: Vertical Flies at B.S. Ricks Memorial Library of the Yazoo Library Association| 310 N. Main Street, Yazoo City, Mississippi 39194 i/p- 4C,THE YAZOO HERALD PROFILE EDITION, SATURDAY, APRIL 24, 2004 Yazoo's Gordon: legendary Hollywood producer Spanning four decades, Lawrence Gordon n^s maintained a career as one oi the entertainment industry s most prolific and successful producers. He has been behind such timeless films as Field of Dreams," which was nominated for several Oscars, including Best Picture; the landmark action film "Die Hard" and the ultimate buddy picture, "48 Hrs." starring Eddie Murphy and Nick Nolte. Born in Yazoo City, Gordon graduated from Tulane University with a degree in business administration. Upon moving to Los Angeles in the early '60s, he went to work as executive assistant to Aaron Spelling at Four Star Television and soon became a writer and associate producer of many Spelling shows. He followed with a stint as head of West Coast talent development for ABC Television and later as an executive with Bob Banner Associates. In 1968, he joined Sam Arkoff and Jim Nicholson at American International Pictures (AIP) as vice president in charge of project development. He then moved to Screen Gems, the television division of Columbia Pictures as vice president, where he » w.w, ; helped develop the classic it television movie, "Brian's Song," as well as the first "novel for television," the adaptation of Leon Uris' "QB VII." Accepting an offer to become the first executive in the company's history to be in charge of worldwide production, Gordon returned to AIP. -

Schindler's List: Myth, Movie, and Memory the Village Voice; Mar 29, 1994~ 39, 13~ Alt-Press Watch (APW) Pg

, Schindler's List: Myth, movie, and memory The Village Voice; Mar 29, 1994~ 39, 13~ Alt-Press Watch (APW) pg. 24 -:~\ In an aEe when even children understand that the image of an event transcends the event itself, Schindler's List is obviously more than just a movie. As with Platoon more than a half dozen years ago, we are enjoined to see a film and understand-but understand what? If nothing else, Oscar night demonstrated that the existence of Schindler's List justi fies Hollywood to Hollywood. The day that Schindler's List opened, New York Times reviewer Janet Maslin declared that "Mr. Spielberg has made sure that neither he nor the Holocaust will ever be thought of in the same way again." That same week, in The Nev.' Yorker, Terrence Rafferty wrote that, with Spielberg dramatizing the liquidation of the Krak6w ghetto. "the Holocaust, 50 years removed from our contemporary con sciousness. suddenly becomes overwhelm ingly immediate, undeniable." Since then, Schindler ~~ List has been used to prove the extent of Jewish suffering-an object lesson for American school children, Nation of Islam spokespeople, and German digni '·Schindl.r'. Li.t puts me in touch wit taries alike. th.t is connected to the part of mys.lf Why does it take a Hollywood fiction to make the Holocaust "undeniable"; Is it with the event. the act of memory with true that movies have the power to perma actual participation, Spielberg himself has nently alter history? Does Schindler's List become a heroic and representative figure. refer to anything beyond itseW! From the (In a leHer sent to many members of the liberation of Auschwitz on, the representa National Society of Film Critics, he spoke tion of the Holocaust has always been un for the totality of the Jewish Holocaust: derstood as problematic. -

This Is the American Film Institute's List of the 100 Greatest Movies, Selected by AFI's Blue-Ribbon Panel of More Than 1,500 Leaders of the American Movie Community

This is the American Film Institute's list of the 100 Greatest Movies, selected by AFI's blue-ribbon panel of more than 1,500 leaders of the American movie community. 1.CITIZEN KANE (1941) 2.CASABLANCA (1942) 3.GODFATHER, THE (1972) 4.GONE WITH THE WIND (1939) 5.LAWRENCE OF ARABIA (1962) 6.WIZARD OF OZ, THE (1939) 7.GRADUATE, THE (1967) 8.ON THE WATERFRONT (1954) 9.SCHINDLER'S LIST (1993) 10.SINGIN' IN THE RAIN (1952) 11.IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE (1946) 12.SUNSET BOULEVARD (1950) 13.BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI, THE (1957) 14.SOME LIKE IT HOT (1959) 15.STAR WARS (1977) 16.ALL ABOUT EVE (1950) 17.AFRICAN QUEEN, THE (1951) 18.PSYCHO (1960) 19.CHINATOWN (1974) 20.ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO'S NEST (1975) 21.GRAPES OF WRATH, THE (1940) 22.2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968) 23.MALTESE FALCON, THE (1941) 24.RAGING BULL (1980) 25.E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL (1982) 26.DR. STRANGELOVE (1964) 27.BONNIE & CLYDE (1967) 28.APOCALYPSE NOW (1979) 29.MR. SMITH GOES TO WASHINGTON (1939) 30.TREASURE OF THE SIERRA MADRE (1948) 31.ANNIE HALL (1977) 32.GODFATHER PART II, THE (1974) 33.HIGH NOON (1952) 34.TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD (1962) 35.IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (1934) 36.MIDNIGHT COWBOY (1969) 37.BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES, THE (1946) 38.DOUBLE INDEMNITY (1944) 39.DOCTOR ZHIVAGO (1965) 40.NORTH BY NORTHWEST (1959) 41.WEST SIDE STORY (1961) 42.REAR WINDOW (1954) 43.KING KONG (1933) 44.BIRTH OF A NATION, THE (1915) 45.STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE, A (1951) 46.CLOCKWORK ORANGE, A (1971) 47.TAXI DRIVER (1976) 48.JAWS (1975) 49.SNOW WHITE & THE SEVEN DWARFS (1937) 50.BUTCH CASSIDY & THE SUNDANCE KID (1969) 51.PHILADELPHIA STORY, THE(1940) AFI is a trademark of the American Film Institute. -

National Film Registry Titles Listed Alphabetically

National Film Registry Titles Selected 1989-2017, Listed Alphabetically Year Year Title Released Inducted 3:10 to Yuma 1957 2012 The 7th Voyage of Sinbad 1958 2008 12 Angry Men 1957 2007 13 Lakes 2004 2014 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea 1916 2016 42nd Street 1933 1998 2001: A Space Odyssey 1968 1991 Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein 1948 2001 Ace in the Hole (aka Big Carnival, The) 1951 2017 Adam’s Rib 1949 1992 The Adventures of Robin Hood 1938 1995 The African Queen 1951 1994 Airplane! 1980 2010 Alien 1979 2002 All About Eve 1950 1990 All My Babies 1953 2002 All Quiet on the Western Front 1930 1990 All That Heaven Allows 1955 1995 All That Jazz 1979 2001 All the King’s Men 1949 2001 All the President’s Men 1976 2010 Allures 1961 2011 America, America 1963 2001 American Graffiti 1973 1995 An American in Paris 1951 1993 Anatomy of a Murder 1959 2012 Annie Hall 1977 1992 Antonia: A Portrait of the Woman 1974 2003 The Apartment 1960 1994 Apocalypse Now 1979 2000 Applause 1929 2006 The Asphalt Jungle 1950 2008 Atlantic City 1980 2003 The Atomic Café 1982 2016 The Augustas 1930s-1950s 2012 The Awful Truth 1937 1996 National Film Registry Titles Selected 1989-2017, Listed Alphabetically Year Year Title Released Inducted Baby Face 1933 2005 Back to the Future 1985 2007 The Bad and the Beautiful 1952 2002 Badlands 1973 1993 Ball of Fire 1941 2016 Bambi 1942 2011 The Band Wagon 1953 1995 The Bank Dick 1940 1992 The Bargain 1914 2010 The Battle of San Pietro 1945 1991 The Beau Brummels 1928 2016 Beauty and the Beast 1991 2002 Being There 1979 -

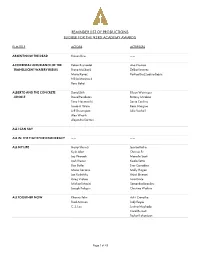

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 93Rd Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 93RD ACADEMY AWARDS FILM TITLE ACTORS ACTRESSES ABSENT NOW THE DEAD Kieran Bew —— ACCIDENTAL LUXURIANCE OF THE Rakan Rushaidat Ana Vilenica TRANSLUCENT WATERY REBUS Frano Mašković Željka Veverec Mario Kovač Pavlica Brazzoduro Bajsić Nikša Marinović Boris Bakal ALBERTO AND THE CONCRETE David Shih Eileen Weisinger JUNGLE David Pendleton Brittany Mirabilé Tony Naumovski Sonia Couling Jacob A. Ware Rami Margron Jeff Greenspan Julie Voshell Alex Wraith Alejandro Santoni ALL I CAN SAY —— —— ALL IN: THE FIGHT FOR DEMOCRACY —— —— ALL MY LIFE Harry Shum Jr Jessica Rothe Kyle Allen Chrissie Fit Jay Pharoah Marielle Scott Josh Brener Keala Settle Dan Butler Ever Carradine Mario Cantone Molly Hagan Jon Rudnitsky Anjali Bhimani Greg Vrotsos Lara Grice Michael Masini Samantha Beaulieu Joseph Poliquin Christina Watkins ALL TOGETHER NOW Rhenzy Feliz Auliʻi Cravalho Fred Armisen Judy Reyes C. S. Lee Justina Machado Carol Burnett Taylor Richardson Page 1 of 45 FILM TITLE ACTORS ACTRESSES ALONE Anthony Heald Jules Willcox Marc Menchaca AMERICAN SKIN Nate Parker Milauna Jackson Omari Hardwick Vanessa Bell Calloway Beau Knapp AnnaLynne McCord Theo Rossi Sierra Capri Shane Paul McGhie Mo McRae Tony Espinosa Michael Warren Allius Barnes Wolfgang Bodison AMMONITE James McArdle Kate Winslet Alec Secareanu Saoirse Ronan Gemma Jones Fiona Shaw AND THEN WE DANCED Levan Gelbakhiani Ana Javakhishvili Bachi Valishvili ANOTHER ROUND Mads Mikkelsen —— ANTEBELLUM —— Janelle Monáe ANTON Nikita Shlanchak Natalia Ryumina Regimantas -

PULP FICTION - a CULT MOVIE? Written by Sven Winnefeld

PULP FICTION - A CULT MOVIE? written by Sven Winnefeld Friedrich Dessauer Gymnasium Aschaffenburg Schuljahr 2004/2006 Facharbeit im Leistungskurs Englisch Thema: "Pulp Fiction - a cult movie?" Verfasser: Sven Winnefeld Tag der Abgabe: 27. Januar 2006 Bewertung: 14 Punkte Note: 1 1 Table of Contents Introduction 4 1 What is a cult movie? 4 1.1 Definition 4 1.2 The history of cult films 5 2 Pulp Fiction 6 2.1 Plot 7 2.1.1 Non-chronological order 7 2.1.2 Correct time sequence 8 2.2 Trivia and theories 10 2.2.1 Little details 10 2.2.2 Emerging questions 11 2.2.3 The mysterious briefcase 12 2.3 Moral standards 13 2.3.1 The banality of murder 13 2.3.2 Redemption 14 2.3.3 Loyalty 15 2.4 Style 15 2.4.1 Dialogue 15 2.4.2 The "Tarantino Universe" 16 Conclusion 18 Bibliography 19 Contact 19 2 cult / k lt / n. 1. a. A religion or religious sect generally considered to be extremist or false, with its followers often living in an unconventional manner under the guidance of an authoritarian, charismatic leader. b. The followers of such a religion or sect. 2. A system or community of religious worship and ritual. 3. The formal means of expressing religious reverence; religious ceremony and ritual. 4. A usually nonscientific method or regimen claimed by its originator to have exclusive or exceptional power in curing a particular disease. 5. a. Obsessive, especially faddish, devotion to or veneration for a person, principle, or thing. -

Entered Film List

ENTERED FILMS LIST 2020/21 The films listed are those which have been entered by film distributors and producers. Every endeavour has been made to ensure that these listings are as accurate as possible. 1. Best Film Entries A list of films which have been entered into Best Film. This list also indicates whether the film has been entered into any of the following categories Director Original or Adapted Screenplay Casting Cinematography Costume Design Editing Make Up & Hair Original Score Production Design Special Visual Effects (SVFX) Sound 2. Performance categories A list of performers entered into the four Acting categories (by film) 3. Animated Film entries 4. Documentary entries 5. Film Not in the English Language entries 6. Outstanding British Film entries 1. BEST FILM ENTRIES Director Screenplay Cast Cinematography Cost Editing Up Make Original Design P SVFX Sound rod ume Design ume ing uction Title Score & Hair & 23 Walks Yes Original 76 Days Yes Yes Yes About Endlessness Yes Original Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes African Apocalypse Yes Yes Yes All In: The Fight For Democracy Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Ammonite Yes Original Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes And Then We Danced Yes Original Yes Another Round Yes Original Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Apples Yes Original Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Archive Yes Original Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Around the Sun Yes Original Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Asia Yes Original Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Assassins Yes Yes The Assistant Yes Original Yes Athlete A Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Atlantis