The Determinants of Retail Tyre Price Dispersion in the Uk*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FTSE Factsheet

FTSE COMPANY REPORT Share price analysis relative to sector and index performance AA AA. General Retailers — GBP 0.25 at close 03 August 2020 Absolute Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Sector Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Index PERFORMANCE 03-Aug-2020 03-Aug-2020 03-Aug-2020 0.7 140 140 1D WTD MTD YTD 130 130 Absolute 4.6 4.6 4.6 -57.0 0.6 Rel.Sector 2.4 2.4 2.4 -48.8 120 120 Rel.Market 2.5 2.5 2.5 -46.1 110 110 0.5 100 100 VALUATION 90 0.4 90 80 Trailing Relative Price Relative Relative Price Relative 80 70 0.3 PE 1.6 70 Absolute Price (local currency) (local Price Absolute 60 EV/EBITDA 8.0 60 50 0.2 PB -ve 50 40 PCF 0.7 0.1 40 30 Div Yield 2.6 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Price/Sales 0.1 Absolute Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Net Debt/Equity - 100 90 90 Div Payout 4.6 90 80 80 ROE - 80 70 70 70 Index) Share Share Sector) Share - - 60 60 60 DESCRIPTION 50 50 50 40 40 The principal activity of the Company is providing 40 RSI RSI (Absolute) service of consumer roadside assistance. -

Full Property Address Primary Liable

Full Property Address Primary Liable party name 2019 Opening Balance Current Relief Current RV Write on/off net effect 119, Westborough, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1LP The Edinburgh Woollen Mill Ltd 35249.5 71500 4 Dnc Scaffolding, 62, Gladstone Lane, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 7BS Dnc Scaffolding Ltd 2352 4900 Ebony House, Queen Margarets Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 2YH Mj Builders Scarborough Ltd 6240 Small Business Relief England 13000 Walker & Hutton Store, Main Street, Irton, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4RH Walker & Hutton Scarborough Ltd 780 Small Business Relief England 1625 Halfords Ltd, Seamer Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO12 4DH Halfords Ltd 49300 100000 1st 2nd & 3rd Floors, 39 - 40, Queen Street, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1HQ Yorkshire Coast Workshops Ltd 10560 DISCRETIONARY RELIEF NON PROFIT MAKING 22000 Grosmont Co-Op, Front Street, Grosmont, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 5QE Grosmont Coop Society Ltd 2119.9 DISCRETIONARY RURAL RATE RELIEF 4300 Dw Engineering, Cholmley Way, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO22 4NJ At Cowen & Son Ltd 9600 20000 17, Pier Road, Whitby, North Yorkshire, YO21 3PU John Bull Confectioners Ltd 9360 19500 62 - 63, Westborough, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1TS Winn & Co (Yorkshire) Ltd 12000 25000 Des Winks Cars Ltd, Hopper Hill Road, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 3YF Des Winks [Cars] Ltd 85289 173000 1, Aberdeen Walk, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, YO11 1BA Thomas Of York Ltd 23400 48750 Waste Transfer Station, Seamer, Scarborough, North Yorkshire, -

UK Annual Report 2015 (Including the Transparency Report)

Investing to become the Clear Choice UK Annual Report 2015 (including the Transparency Report) December 2015 KPMG.com/uk Highlights Strategic report Profit before tax and Revenue members’ profit shares £1,958m £383m (2014: £1,909m) (2014: £414m) +2.6% -7% 2013 2014 2015 2013 2014 2015 Average partner Total tax payable remuneration to HMRC £623k £786m (2014: £715K) (2014: £711m) -13% +11% 2013 2014 2015 2013 2014 2015 Contribution Our people UK employees KPMG LLP Annual Report 2015 Annual Report KPMG LLP 11,652 Audit Advisory Partners Tax 617 Community support Organisations supported Audit Tax Advisory Contribution Contribution Contribution £197m £151m £308m (2014: £181m) (2014: £129m) (2014: £324m) 1,049 +9% +17% –5% (2014: 878) © 2015 KPMG LLP, a UK limited liability partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. Strategic report Contents Strategic report 4 Chairman’s statement 10 Strategy 12 Our business model 16 Financial overview 18 Audit 22 Solutions 28 International Markets and Government 32 National Markets 36 People and resources 40 Corporate Responsibility 46 Our taxes paid and collected 47 Independent limited assurance report Governance 52 Our structure and governance 54 LLP governance 58 Activities of the Audit & Risk Committee in the year 59 Activities of the Nomination & Remuneration Committee in the year KPMG in the UK is one of 60 Activities of the Ethics Committee in the year 61 Quality and risk management the largest member firms 2015 Annual Report KPMG LLP 61 Risk, potential impact and mitigations of KPMG’s global network 63 Audit quality indicators 66 Statement by the Board of KPMG LLP providing Audit, Tax and on effectiveness of internal controls and independence Advisory services. -

Find Your Nearest Site

Find your nearest site Scotland Northern Ireland North East Isle of Man Yorkshire and the Humber North West East Midlands Wales West Midlands East of England Greater London South West South East East Midlands Site name Phone number Address Town/City Post code PRESTIGE - PROMECH GARAGE SERVICES 01664 503467 UNIT 3B ARNOLD NG5 7FJ PRESTIGE - AUTOMOTO CAR CARE CENTRE 01664 503467 33-41 HIGH ROAD BEESTON NG9 4AF STONEACRE PETERBOROUGH BOONGATE 01405 744192 FORTY ACRE ROAD BOONGATE PE1 5PS PRESTIGE - BOSTON TYRE & AUTO CENTRE 01664 503467 46 FYDELL STREET BOSTON PE21 8LF VERTU HONDA BOSTON 1 MARSH LANE BOSTON PE21 7QS NTA COALVILLE LEICS (503) 01530 834321 26 ASHBY ROAD COALVILLE LE67 3LA PRESTIGE - ANDERSON COMMERCIALS LTD 01664 503467 UNIT 7-8 SOUTH STREET COALVILLE LE67 1EU NTA CORBY NORTHANTS (495) 01536 203508 LLOYDS ROAD CORBY NN17 1AW PRESTIGE - CORBY CAR CARE CENTRE 01664 503467 3 CURIE COURTYARD CORBY NN17 5DU PRESTIGE - M & A CARS LTD 01664 503467 11 WHITTLE ROAD CORBY NN17 5DX HALFORDS GRANTHAM (677) 01476 591435 LONDON ROAD GRANTHAM NG31 6HS NTA GRANTHAM (655) 01476 575887 68 LONDON ROAD GRANTHAM NG31 6HR PRESTIGE - GRANTHAM SERVICE & MOT CENTRE 01664 503467 UNIT 1 ALMA PARK ROAD GRANTHAM NG31 9SE STONEACRE GRANTHAM 01405 744192 TOLLEMACHE ROAD SOUTH GRANTHAM NG31 7UH HALFORDS NOTTINGHAM HUCKNALL (210) 0115 963 8825 UNIT 4 CHRISTOPHER COURT HUCKNALL NG15 6EP PRESTIGE - ROMANS TYRES & EXHAUST LTD 01664 503467 11 STONEHILL HUNTINGDON PE29 6ED HALFORDS KETTERING (005) 01536 410421 TRAFALGAR ROAD KETTERING NN16 8DB PRESTIGE - SIGNATURE -

THE CARS of Will.I.Am WIN a RANGE ROVER EVOQUE with BRITAX

MAX MPG MERCEDES IDRIS ELBA & JAG XE £5K MINI COOPER FRILLY SEAT Mii THE CARS OF will.i.am WIN A RANGE ROVER EVOQUE WITH BRITAX freecarmag.co.uk 1 GET YOUR SMART FINGER OUT AND FIND THE RIGHT CAR FOR YOU Find 1000s of history checked cars near you Untitled-1 1 03/03/2015 09:14:35 Smart finger - Smart Search - 230x280.indd 1 27/02/2015 16:48 GET YOUR SMART FINGER OUT AND ISSUE 01 / 2015 FIND THE RIGHT CAR FOR YOU this week elcome to Free Car Mag. We are Wdifferent to other car magazines, not only because we are actually free, but free to think and do things differently. At Free Car Mag we are committed to bringing you stories, pictures and information that you will find genuinely useful, amusing, provocative, odd, silly and fun. Free Car Mag will tell you what’s going on in the four wheeled (and sometimes two-wheeled) world without getting all precious and pretentious about it. This is a magazine for you so we want to know what you think. Tell us what we can do better and ask us questions. Do that via our brilliant website which will also help you value a car, buy another and how to run one for less. Free Car Mag love cars and driving them, but we don’t believe it has to be complicated. No one really needs to know how to change a water pump, unless they really want to. Free Car Mag promises never to use any boring technical terms and if you spot the word crankshaft in these pages we will send you a cheque for £100. -

GMO Trust Semiannual Report August 31, 2020

GMO Trust Semiannual Report August 31, 2020 Climate Change Fund Cyclical Focus Fund Emerging Domestic Opportunities Fund Emerging Markets Fund International Equity Fund Quality Fund Resources Fund Risk Premium Fund Tax-Managed International Equities Fund U.S. Equity Fund U.S. Small Cap Value Fund Beginning on January 1, 2021, as permitted by regulations adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission, GMO expects that paper copies of each Fund’s annual and semiannual reports to shareholders will no longer be sent by mail, unless you specifically request paper copies of the reports by writing or calling GMO Shareholder Services at the address or phone number below or by contacting your financial intermediary, such as a broker or agent. Instead, reports will be available on a website, and you will be notified by mail each time a report is posted and provided with a website link to access the report. If you already elected to receive shareholder reports electronically, you will not be affected by this change and you need not take any action. If you are a direct investor, you may elect to receive shareholder reports and other communications from the Fund electronically by contacting GMO Shareholder Services or if you own your shares through a financial intermediary, you may contact your financial intermediary. Beginning January 1, 2019, you may elect to receive all future reports in paper free of charge. If you invest through a financial intermediary, you can contact your financial intermediary to request to continue to receive paper copies of your shareholder reports or you can follow instructions included with this disclosure. -

Annual Investment Report 2015-2016

South Carolina Retirement System Investment Commission 2015-2016 Annual Investment Report Photos courtesy of the Governor’s Office and the SC National Guard. South Carolina Retirement System Investment Commission Annual Investment Report Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2016 Capitol Center 1201 Main Street, Suite 1510 Columbia, SC 29201 Edward Giobbe, MBA Chair For the period July 1, 2014 - June 30, 2016 Table of Contents Chair Report .....................................................................................................1 Consultant’s Letter ............................................................................................3 Overview ...........................................................................................................5 Commission ......................................................................................................6 Policy Allocation ...............................................................................................9 Manager Returns (Net of Fees) .......................................................................10 Securities Lending ..........................................................................................14 Expenses ..........................................................................................................15 Risk ..................................................................................................................17 Appendix Appendix A: Summary Schedule of Assets and Derivatives .....................19 Appendix B: Cash & -

To Let / for Sale Offices / Industrial / Technology 10,000 - 500,000 Sq Ft

JUNCTION 6 - M5 WR4 0AD TO LET / FOR SALE OFFICES / INDUSTRIAL / TECHNOLOGY 10,000 - 500,000 SQ FT www.worcestersix.co.uk A development by WORCESTER SIX OVERVIEW Worcester Six provides an unrivalled opportunity across the West Midlands for new, sustainable buildings that will enable businesses to thrive in a world-class location. When complete, Worcester Six will provide circa 1.5m sq ft of employment floor space in a unique business environment and now benefits from over 700,000 sq ft having been delivered or committed across the scheme. The quality of life in Worcestershire makes relocation very attractive with a rich historical and natural heritage, world-class sporting and cultural attractions and top performing schools. M54 A34 Leicester A41 Wolverhampton A6 A5 A449 Dudley M6 A458 Birmingham M1 M6 A442 A45 M5 M42 Coventry A441 A34 Kidderminster A38 Rugby A14 STRATEGICALLY A448 M42 Bromsgrove A46 M45 A423 A435 A449 Redditch Warwick M5 PLACED M40 6 A46 Worcester A44 7 A5 Worcester 6 A46 A44 Evesham A429 A449 A46 M50 M5 A44 Cheltenham Gloucester A48 M40 A40 Oxford DRIVE TIMES M42 (Junction 1) 11 miles 13 mins Bristol 63 miles 63 mins M40 (Junction 16) 24 miles 23 mins London 128 miles 157 mins M6 (Junction 8) 30 miles 37 mins Birmingham International Airport 32 miles 38 mins Birmingham 25 miles 35 mins Jaguar Land Rover (Solihull) 31 miles 43 mins INDICATIVE M5, JCT 6 FUTURE DEVELOPMENT SPECIFICATION Unit 5A COMPLETED BUILDINGS ACCOMMODATION 2 2 2 Commercial ft Office ft Total ft Unit 5B Unit 1A (B1) - 37,975 37,975 Build to suit units are available, tailored to Unit 1B 56,400 - 56,400 your business needs, in a secure, managed and Unit 2A Cornelius landscaped setting. -

To Let / for Sale Offices / Industrial / Technology 10,000 - 500,000 Sq Ft

JUNCTION 6 - M5 WR4 0AD TO LET / FOR SALE OFFICES / INDUSTRIAL / TECHNOLOGY 10,000 - 500,000 SQ FT www.worcestersix.co.uk A development by WORCESTER SIX OVERVIEW Worcester Six provides an unrivalled opportunity across the West Midlands for new, sustainable buildings that will enable businesses to thrive in a world-class location. When complete, Worcester Six will provide circa 1.5m sq ft of employment floor space in a unique business environment and now benefits from over 700,000 sq ft having been delivered or committed across the scheme. The quality of life in Worcestershire makes relocation very attractive with a rich historical and natural heritage, world-class sporting and cultural attractions and top performing schools. M54 A34 Leicester A41 Wolverhampton A6 A5 A449 Dudley M6 A458 Birmingham M1 M6 A442 A45 M5 M42 Coventry A441 A34 Kidderminster A38 Rugby A14 STRATEGICALLY A448 M42 Bromsgrove A46 M45 A423 A435 A449 Redditch Warwick M5 PLACED M40 6 A46 Worcester A44 7 A5 Worcester 6 A46 A44 Evesham A429 A449 A46 M50 M5 A44 Cheltenham Gloucester A48 M40 A40 Oxford DRIVE TIMES M42 (Junction 1) 11 miles 13 mins Bristol 63 miles 63 mins M40 (Junction 16) 24 miles 23 mins London 128 miles 157 mins M6 (Junction 8) 30 miles 37 mins Birmingham International Airport 32 miles 38 mins Birmingham 25 miles 35 mins Jaguar Land Rover (Solihull) 31 miles 43 mins INDICATIVE M5, JCT 6 FUTURE DEVELOPMENT SPECIFICATION Uit 5A COMPLETED BUILDINGS ACCOMMODATION 2 2 2 Commercial ft Office ft Total ft Uit 5B Unit 1A (B1) - 37,975 37,975 Build to suit units are available, tailored to Unit 1B 56,400 - 56,400 your business needs, in a secure, managed and Unit 2A Cornelius landscaped setting. -

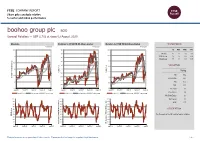

FTSE Factsheet

FTSE COMPANY REPORT Share price analysis relative to sector and index performance boohoo group plc BOO General Retailers — GBP 2.703 at close 03 August 2020 Absolute Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Sector Relative to FTSE UK All-Share Index PERFORMANCE 03-Aug-2020 03-Aug-2020 03-Aug-2020 4.5 190 220 1D WTD MTD YTD 180 Absolute 3.6 3.6 3.6 -9.3 200 4 Rel.Sector 1.4 1.4 1.4 8.0 170 Rel.Market 1.5 1.5 1.5 13.7 160 180 3.5 150 VALUATION 160 3 140 Trailing 140 Relative Price Relative Relative Price Relative 130 2.5 PE 75.6 120 Absolute Price (local currency) (local Price Absolute 120 EV/EBITDA 39.0 110 2 100 PB 15.5 100 PCF 41.1 1.5 90 80 Div Yield 0.0 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Price/Sales 3.9 Absolute Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Relative Price 4-wk mov.avg. 13-wk mov.avg. Net Debt/Equity 0.1 100 100 100 Div Payout 0.0 90 90 90 ROE 22.7 80 80 80 70 70 Index) Share 70 Share Sector) Share - - 60 60 60 DESCRIPTION 50 50 50 40 40 40 The Company is the UK`s online fashion retailers. RSI RSI (Absolute) 30 30 30 20 20 20 10 10 10 RSI (Relative to FTSE UKFTSE All to RSI (Relative RSI (Relative to FTSE UKFTSE All to RSI (Relative 0 0 0 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Aug-2019 Nov-2019 Feb-2020 May-2020 Aug-2020 Past performance is no guarantee of future results. -

M Funds Quarterly Holdings 3.31.2020*

M International Equity Fund 31-Mar-20 CUSIP SECURITY NAME SHARES MARKET VALUE % OF TOTAL ASSETS 233203421 DFA Emerging Markets Core Equity P 2,263,150 35,237,238.84 24.59% 712387901 Nestle SA, Registered 22,264 2,294,710.93 1.60% 711038901 Roche Holding AG 4,932 1,603,462.36 1.12% 690064001 Toyota Motor Corp. 22,300 1,342,499.45 0.94% 710306903 Novartis AG, Registered 13,215 1,092,154.20 0.76% 079805909 BP Plc 202,870 863,043.67 0.60% 780087953 Royal Bank of Canada 12,100 749,489.80 0.52% ACI07GG13 Novo Nordisk A/S, Class B 12,082 728,803.67 0.51% B15C55900 Total SA 18,666 723,857.50 0.51% 098952906 AstraZeneca Plc 7,627 681,305.26 0.48% 406141903 LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton S 1,684 625,092.87 0.44% 682150008 Sony Corp. 10,500 624,153.63 0.44% B03MLX903 Royal Dutch Shell Plc, Class A 35,072 613,753.12 0.43% 618549901 CSL, Ltd. 3,152 571,782.15 0.40% ACI02GTQ9 ASML Holding NV 2,066 549,061.02 0.38% B4TX8S909 AIA Group, Ltd. 60,200 541,577.35 0.38% 677062903 SoftBank Group Corp. 15,400 539,261.93 0.38% 621503002 Commonwealth Bank of Australia 13,861 523,563.51 0.37% 092528900 GlaxoSmithKline Plc 26,092 489,416.83 0.34% 891160954 Toronto-Dominion Bank (The) 11,126 473,011.14 0.33% B1527V903 Unilever NV 9,584 472,203.46 0.33% 624899902 KDDI Corp. -

Agenda Item 10

Agenda Item 10 Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council Report to Cabinet Member for Neighbourhoods and Housing 13th July 2007 Highways Direct Orders, Contracts and Select List for the Supply of Specialist Vehicles and Plant 1. Summary Statement 1.1 The Council’s Standing Orders relating to contracts were revised in July 2002 to accord with the models provided by the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) also published in July 2002. 1.2 Under the revised orders, for purchases/services of £1,101 to £40,000, if at least three quotations cannot be obtained approval must be obtained from the appropriate Chief Officer and the matter reported to the appropriate Cabinet Member at his/her next public decision making session (Cabinet Advisory Team). 1.3 For purchases/services of £40,000 and below £100,000 where four tenders are not to be invited, the approval of the appropriate Chief Officer, must be obtained, in consultation with the appropriate Cabinet Member, and the matter reported to the Cabinet Member at his/her next public decision making session (Cabinet Advisory Team). 1.4 There is also a requirement to report back to the Cabinet Member on any contracts awarded in excess of £40,000. 1.5 Details of those orders and contracts are listed in Appendix A. 1.6 Following the expiry of the existing tenders, a review of the Council’s provision for the supply of vehicles and plant was undertaken by the Purchasing Services Office and Fleet Management and Maintenance. 1.7 In conjunction with other local authorities, the Council has joined ‘The Procurement Partnership’ which is a purchasing consortium.