A Highly-Textual Affair: the Sylvander-Clarinda Correspondence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Letters of Robert Burns 1

The Letters of Robert Burns 1 The Letters of Robert Burns The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Letters of Robert Burns, by Robert Burns #3 in our series by Robert Burns Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. The Letters of Robert Burns 2 **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: The Letters of Robert Burns Author: Robert Burns Release Date: February, 2006 [EBook #9863] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on October 25, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LETTERS OF ROBERT BURNS *** Produced by Charles Franks, Debra Storr and PG Distributed Proofreaders BURNS'S LETTERS. THE LETTERS OF ROBERT BURNS, SELECTED AND ARRANGED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY J. -

RBWF Burns Chronicle Index

A Directory To the Articles and Features Published in “The Burns Chronicle” 1892 – 2005 Compiled by Bill Dawson A “Merry Dint” Publication 2006 The Burns Chronicle commenced publication in 1892 to fulfill the ambitions of the recently formed Burns Federation for a vehicle for “narrating the Burnsiana events of the year” and to carry important articles on Burns Clubs and the developing Federation, along with contributions from “Burnessian scholars of prominence and recognized ability.” The lasting value of the research featured in the annual publication indicated the need for an index to these, indeed the 1908 edition carried the first listings, and in 1921, Mr. Albert Douglas of Washington, USA, produced an index to volumes 1 to 30 in “the hope that it will be found useful as a key to the treasures of the Chronicle” In 1935 the Federation produced an index to 1892 – 1925 [First Series: 34 Volumes] followed by one for the Second Series 1926 – 1945. I understand that from time to time the continuation of this index has been attempted but nothing has yet made it to general publication. I have long been an avid Chronicle collector, completing my first full set many years ago and using these volumes as my first resort when researching any specific topic or interest in Burns or Burnsiana. I used the early indexes and often felt the need for a continuation of these, or indeed for a complete index in a single volume, thereby starting my labour. I developed this idea into a guide categorized by topic to aid research into particular fields. -

“Epistolary Performances”: Burns and the Arts of the Letter Kenneth Simpson

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Robert Burns and Friends Robert Burns Collections 1-1-2012 “Epistolary Performances”: Burns and the arts of the letter Kenneth Simpson Publication Info 2012, pages 58-67. © The onC tributors, 2012 All rights reserved Printed and distributed by CreateSpace https://www.createspace.com/900002089 Editorial contact address: Patrick Scott, c/o Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, University of South Carolina Libraries, 1322 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4392-7097-4 Scott, P., Simpson, K., eds. (2012). Robert Burns & Friends essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy. P. Scott & K. Simpson (Eds.). Columbia, SC: Scottish Literature Series, 2012. This Chapter is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Burns and Friends by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Epistolary Performances”: Burns and the arts of the letter1 Kenneth Simpson Scholarship increasingly identifies Burns as a multi-voiced poet, a sophisticated literary artist, and a complex human being. His letters repay scrutiny in terms of the various qualities they reveal: the reflection of the wide range of Burns’s reading, his remarkable powers of recall, and his capacity for mimicry; the diversity of voices and styles employed, indicating a considerable dramatic talent; the narrative verve and mastery of rhetoric that mark him out as the novelist manqué; and the psychological implications, in that the chameleon capacity of Burns the writer exacerbates the problems of identity of Burns the man. -

ROBERT BURNS and FRIENDS Essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows Presented to G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Robert Burns and Friends Robert Burns Collections 1-1-2012 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy Patrick G. Scott University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Kenneth Simpson See next page for additional authors Publication Info 2012, pages 1-192. © The onC tributors, 2012 All rights reserved Printed and distributed by CreateSpace https://www.createspace.com/900002089 Editorial contact address: Patrick Scott, c/o Irvin Department of Rare Books & Special Collections, University of South Carolina Libraries, 1322 Greene Street, Columbia, SC 29208, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4392-7097-4 Scott, P., Simpson, K., eds. (2012). Robert Burns & Friends essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy. P. Scott & K. Simpson (Eds.). Columbia, SC: Scottish Literature Series, 2012. This Book - Full Text is brought to you by the Robert Burns Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Robert Burns and Friends by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Author(s) Patrick G. Scott, Kenneth Simpson, Carol Mcguirk, Corey E. Andrews, R. D. S. Jack, Gerard Carruthers, Kirsteen McCue, Fred Freeman, Valentina Bold, David Robb, Douglas S. Mack, Edward J. Cowan, Marco Fazzini, Thomas Keith, and Justin Mellette This book - full text is available at Scholar Commons: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/burns_friends/1 ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. Ormiston Roy Fellows presented to G. Ross Roy G. Ross Roy as Doctor of Letters, honoris causa June 17, 2009 “The rank is but the guinea’s stamp, The Man’s the gowd for a’ that._” ROBERT BURNS AND FRIENDS essays by W. -

Robert Burns and a Red Red Rose Xiaozhen Liu North China Electric Power University (Baoding), Hebei 071000, China

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 311 1st International Symposium on Education, Culture and Social Sciences (ECSS 2019) Robert Burns and A Red Red Rose Xiaozhen Liu North China Electric Power University (Baoding), Hebei 071000, China. [email protected] Abstract. Robert Burns is a well-known Scottish poet and his poem A Red Red Rose prevails all over the world. This essay will first make a brief introduction of Robert Burns and make an analysis of A Red Red Rose in the aspects of language, imagery and rhetoric. Keywords: Robert Burns; A Red Red Rose; language; imagery; rhetoric. 1. Robert Burns’ Life Experience Robert Burns (25 January 1759 – 21 July 1796) is a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is one of the most famous poets of Scotland and is widely regarded as a Scottish national poet. Being considered as a pioneer of the Romantic Movement, Robert Burns became a great source of inspiration to the founders of both liberalism and socialism after his death. Most of his world-renowned works are written in a Scots dialect. And in the meantime, he produced a lot of poems in English. He was born in a peasant’s clay-built cottage, south of Ayr, in Alloway, South Ayrshire, Scotland in 1759 His father, William Burnes (1721–1784), is a self-educated tenant farmer from Dunnottar in the Mearns, and his mother, Agnes Broun (1732–1820), is the daughter of a Kirkoswald tenant farmer. Despite the poor soil and a heavy rent, his father still devoted his whole life to plough the land to support the whole family’s livelihood. -

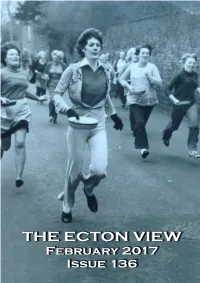

Ecton View Feb 2017

THE ECTON VIEW February 2017 Issue 136 Parish and Village Directory Parish Council Ecton Village Hall Chairman: Sally Bresnahan Bookings: Carol Armstrong 01604 403027 01604 402907 Mobile: 07515 156419 PCC Secretary Youth Club Tom Pearson Contact: Margaret Tinston 10 Ashley Way, Westone 01604 412233 Northampton, NN3 3DZ [email protected] 01604 891109 Wednesdays at Village Hall 07745 133 867 6.00-7.30 Junior Youth Club PCC Treasurer Nigel Bond Short Mat Bowls 01604 948040 Contact: Maurice Creed 01604 407864 Electoral Roll Officer Contact: Mary Dicks EGO’s 01604 407145 Contact: Patricia MacRae Borough Council 01604 402582 of Wellingborough Pre & Primary School Acting Head: Kate Cleaver Councillors 01604 409213 Jennie Bone 07771 681 964 Website Editor [email protected] Thomas Coulter-Brophy Clive Hallam [email protected] 07799 133 301 Front Cover & Photos [email protected] Many thanks to Len Fenn for this photo of Ecton Pancake Race in 1975, and Church Directory Wendy Mills for the photo of ‘Santa’ with Rector Megan. Rev Jackie Buck Church Wardens 01933 631232 Linda Richards [email protected] 01604 405888 Bell Ringers Joy Bond Contact: Jude Coulter 01604 948040 01604 408588 Ecton Church Lottery - Results for December & January 1st £50 Richard Kelly Kim Wheatman 2ⁿd £15 Natasha & Kim Wardley Richard & Alison Greenbank 3rd £10 Bev Wright Sally Meenaghan Editors Notes Welcome to Ecton 2017 and a brand new issue of The Ecton View. I know I should not be surprised but over the festive period you, the Villagers, raised a fantastic amount of money for charity. £456 for The David Cross Fund, after giving all the older people of Ecton a wonderful Christmas Lunch, raised just by signing the Ecton Christmas Card (a record, well done Denise!). -

Burns Chronicle 1909

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1909 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Colin Harris The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com PRICE : JANUARY, 1909. ONE SHlLLINO~SIXPENCE . PRIN TeD BY PUBLISHED BY THE SlJ,RNS fEDERATION, J. MAXWELL & SON, KtLMAR N QC K ., DUMFRIES. KILMARNOCK t· Burns monum~nt. •~' STATUE, LIBRARY, AND JY\.USEUJY\.. " --- VISITED by thousands froin all parts of the W orl~. A verit able Shrine, , of the" Immortal Bard." The Monument occupies a commanding position in the Kay Park. From..the top a most extensive and interesting view of the surrounding Land of Burns can be obtained. The magnificent Marble' Statue of the Poet, from the chisel of W. G. Stevenson, A.R.S.A., Edinburgh, is admitted to be the finest in the Wodd. The Museum contains many relics and mementoes of the Poet's Life, and the most valuable and interesting collection of the original MSS. in existence, among which are the following:- _J Tam 0' 8hanter. The Death and Dyln' Words 0' Poor Cotter's Saturday NIB'ht. Mallle. The Twa Dogs. Poor Mallle's EleD· The Holy Fair. Lassie wI' the Lint-white Locks. Address to the DelL Last May a Braw Wooer oam' doon dohn Barleyoom. the La"g Clen. 800tch Drink. Holy Wlllle's Prayer. The Author's Earnest Cry" prajer. Epistle to a Young Friend. Address to d. 8mlth. Lament of Mary Queen of Scots. -

Burns Chronicle 2012

Burns Chronicle Summer 2012 Making Teacakes for your Thomas Tunnock Ltd., 34 Old Mill Road, Uddingston G71 7HH Tel: 01698 813551 Fax: 01698 815691 01387 262960 Tel: Printers, Dumfries. Email: [email protected] the enjoyment www.tunnock.co.uk Solway Offset Solway Offset 22208_OTM 297x210 1205.indd 1 12/05/2011 14:18 High quality fine wool neck tie THE BURNS FEDERATION1885 – 1985. James A Mackay. A comprehensive account of the history of the Burns Federation, published for the centenary. James Mackay traces the origins and development of the Burns movement over the years since the death of Robert Burns in 1796, with special reference to the Burns Federation. Manufactured in lightweight “Reiver” worsted wool Fourteen chapters covering in depth all aspects of Burns by Lochcarron appreciation and the Federation with detailed appendices. RRP £15.95, The Robert Burns World Federation From the Federation Office at the modest price of President 2011 - 2012, RBWF price £10.00Jim Shields £7.50 plus post and packaging. Burns Chronicle Summer 2012 SUMMER 2012 Contents Editorial ..............................................................................................................................2 No 7 in our series 20th C Burns Scholars, Robert D Thornton. Patrick Scott, University of South Carolina ..........................................................................3 Hamilton Paul: A Forgotten Hero. Clark McGinn .............................................................8 News of our Built Heritage ..............................................................................................13 -

Burns Chronicle 1995

Robert BurnsLimited World Federation Limited www.rbwf.org.uk 1995 The digital conversion of this Burns Chronicle was sponsored by Mrs Helen Morrison The digital conversion service was provided by DDSR Document Scanning by permission of the Robert Burns World Federation Limited to whom all Copyright title belongs. www.DDSR.com BURNS CHRONICLE INCORPORATING "THE BURNSIAN" BICENTENARY of DEATH DECEMBER 1995 VOL. 4 (NEW SERIES) NUMBER 3 BURNS COUNTRY TOURING SOVEREIGN Chauffeur Drive The story of Scotland's National Poet Robert Burns is woven into the Ayrshire countryside which he knew so well. Burns Country holds a warm welcome for visitors, and at SOVEREIGN we offer a touring service tailored to your particular requirements. Whether a Burns expert, an enthusiast, or just curious to find out more about the legend - allow us to help make your visit a memorable one. Please call or write for our brochure and tariff SOVEREIGN Chauffeur Drive, Carrick Cottage, 15 Main Street, Dundonald, Ayrshire. KA2 9HF, Scotland, UK. Telephone: 44 1563850971 Fax: 44 1563850660 (UK Code 01563) Other Services: Airport/ Hotel transfers, Evening Hire, Executive Travel, Touring throughout Scotland and Northern England, SPecial Interest Tours (Castles, Historic Homes) . Members - AYRSHIRE TOURIST BOARD Partners - Catherine and William McKinlay BURNS CHRONICLE INCORPORATING "THE BURNSIAN" Contents DECEMBER 1995 Dumfries Commemoration .................................... 5 Burns's Neighbours in Dumfries ......................... 15 NUMBER 3 How We Licked 'Em ........ .. ....... .. ...... .. ................... 24 The Cheltenham Connection ........................ ..... .. 28 VOL. 5 Robert Burns -A Reverie and a Reminiscence ... 32 My Sketchbook ...................................................... 34 Coilsfield "The Castle 0' Montgomerie" ............ 36 The Passions of Robert Burns .............. ..... .... ... .... 43 Roger Quin, Scotland's Tramp Poet ........ -

The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 6Th Edition

B Bab Ballads, a collection of humorous ballads by W. S. lated by J. Harland in 1929 and most of his work is ^Gilbert (who was called 'Bab' as a child by his parents), available in English translation. first published in Fun, 1866-71. They appeared in Babylon, an old ballad, the plot of which is known 'to volume form as Bab Ballads (1869); More Bab Ballads all branches of the Scandinavian race', of three sisters, (1873); Fifty Bab Ballads (1877). to each of whom in turn an outlaw proposes the alternative of becoming a 'rank robber's wife' or death. Babbitt, a novel by S. *Lewis. The first two chose death and are killed by the outlaw. The third threatens the vengeance of her brother 'Baby BABBITT, Irving (1865-1933), American critic and Lon'. This is the outlaw himself, who thus discovers professor at Harvard, born in Ohio. He was, with Paul that he has unwittingly murdered his own sisters, and Elmer More (1864-1937), a leader of the New Hu thereupon takes his own life. The ballad is in *Child's manism, a philosophical and critical movement of the collection (1883-98). 1920s which fiercely criticized *Romanticism, stress ing the value of reason and restraint. His works include BACH, German family of musicians, of which Johann The New Laokoon (1910), Rousseau and Romanticism Sebastian (1685-1750) has become a central figure in (1919), and Democracy and Leadership (1924). T. S. British musical appreciation since a revival of interest *Eliot, who described himself as having once been a in the early 19th cent, led by Samuel Wesley (1766- disciple, grew to find Babbitt's concept of humanism 1837, son of C. -

The Romantic Letters of Rabbie

George Scott Wilkie Robert Burns His Life In His Letters A Virtual Autobiography A Chronology of Robert Burns 1757 Marriage of William Burnes (1721 – 84) at Clochnahill Farm, Dunnottar, Kincardineshire) to Agnes Broun (1732 – 1820) at Craigenton, Kirkoswald) at Maybole, Ayrshire (15 December). 1759 Birth of Robert Burns at Alloway (25 January) 1760 Gilbert (brother) born. 1762 Agnes (sister) born. (1762 – 1834) 1764 Anabella (sister) born.(1764 – 1832) 1765 Robert and Gilbert are sent to John Murdoch's school at Alloway. 1766 William Burnes rents Mount Oliphant Farm, near Alloway and moves his family there (25 May). 1767 Birth of William Burns (brother) 1767 – 1790). 1768 John Murdoch closes the Alloway school, leaving the Burns brothers to be educated at home by their father. 1769 Birth of John Burns (brother). (1769 – 1785) 1770 Robert and Gilbert assist their father in labouring and farming duties. 1771 Birth of Isabella Burns (sister) (1771 – 1858). 1772 Robert and Gilbert attend Dalrymple Parish School during the summer, but having to go on alternate weeks as one is needed to assist on the farm. 1773 Robert studies grammar and French with John Murdoch for three weeks at Ayr 1774 Robert becomes the principal labourer on his father's farm and writes Handsome Nell in praise of Nellie Kilpatrick. 1777 He joins a dancing class, much to his father's horror. William Burnes moves the family from Mount Oliphant to Lochlea (25 May). Burns spends the summer on the smuggling coast of Kirkoswald and attends school there. 1780 With Gilbert and six other young men, Robert forms the Tarbolton Bachelor's Club. -

Considering Moore's Irish Melodies in Relation to the Songs of Robert

MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Traditions of song: Considering Moore’s Irish Melodies in relation to the songs of Robert Burns Rooney, Sheila Award date: 2020 Awarding institution: Queen's University Belfast Link to publication Terms of use All those accessing thesis content in Queen’s University Belfast Research Portal are subject to the following terms and conditions of use • Copyright is subject to the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, or as modified by any successor legislation • Copyright and moral rights for thesis content are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners • A copy of a thesis may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research/study without the need for permission or charge • Distribution or reproduction of thesis content in any format is not permitted without the permission of the copyright holder • When citing this work, full bibliographic details should be supplied, including the author, title, awarding institution and date of thesis Take down policy A thesis can be removed from the Research Portal if there has been a breach of copyright, or a similarly robust reason. If you believe this document breaches copyright, or there is sufficient cause to take down, please contact us, citing details. Email: [email protected] Supplementary materials Where possible, we endeavour to provide supplementary materials to theses. This may include video, audio and other types of files. We endeavour to capture all content and upload as part of the Pure record for each thesis. Note, it may not be possible in all instances to convert analogue formats to usable digital formats for some supplementary materials.