Brian Burke: "An Analysis of the Rhetorical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

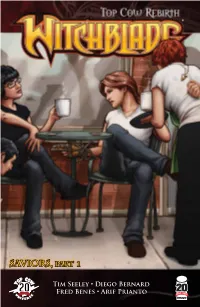

Saviors, PART 1

® Saviors, PART 1 Tim Seeley • Diego Bernard 201992 - 2012 Fred Benes • Arif Prianto Previously In Tim Seeley • writer Diego Bernard • penciller Cover A • John Tyler Christopher Fred Benes • inker Cover B • Diego Bernard, Fred Benes, SAVIORS, Pt. 1 Arif Prianto • colorists & Arif Prianto Troy Peteri • letterer Bryan Rountree, Matt Hawkins, & Filip Sablik • editors Witchblade created by Marc Silvestri, David Wohl, Brian Haberlin, & Michael Turner WITCHBLADE® ISSUE 158. JULY 2012. FIRST PRINTING Published by Image Comics Inc. Office of Publication: 2134 Allston Way, Second Floor, Berkeley, CA For Top Cow Productions, Inc. 94704. $2.99 US. WITCHBLADE® 2012 Top Cow Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. “Witchblade,” the Witchblade logos, and the likenesses of all featured Marc Silvestri - CEO characters (human or otherwise) featured herein are registered trademarks of Top Cow Productions, Inc. Image Comics and the Image Comics logo are Matt Hawkins - President and COO trademarks of Image Comics Inc. The characters, events, and stories in this Bryan Rountree – Managing Editor publication are entirely fictional. Any resemblance to actual persons (living or Elena Salcedo – Director of Operations dead), events, institutions, or locales, without satiric intent, is coincidental. No Betsy Gonia - Production Assistant portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the express written permission of Top Cow Productions, Inc. Printed in the U.S.A. For information regarding the CPSIA on this printed material call: 203-595-3636 and provide reference # RICH – 448584. “The challenge is Trying To capTure imaginaTion wiTh lines. BuT when iT works, comics can Be amazing.” Jason howarD ExpEriEncE crEativity Image Comics® and its logos are registered trademarks of Image Comics, Inc. -

Body Bags One Shot (1 Shot) Rock'n

H MAVDS IRON MAN ARMOR DIGEST collects VARIOUS, $9 H MAVDS FF SPACED CREW DIGEST collects #37-40, $9 H MMW INV. IRON MAN V. 5 HC H YOUNG X-MEN V. 1 TPB collects #2-13, $55 collects #1-5, $15 H MMW GA ALL WINNERS V. 3 HC H AVENGERS INT V. 2 K I A TPB Body Bags One Shot (1 shot) collects #9-14, $60 collects #7-13 & ANN 1, $20 JASON PEARSON The wait is over! The highly anticipated and much debated return of H MMW DAREDEVIL V. 5 HC H ULTIMATE HUMAN TPB JASON PEARSON’s signature creation is here! Mack takes a job that should be easy collects #42-53 & NBE #4, $55 collects #1-4, $16 money, but leave it to his daughter Panda to screw it all to hell. Trapped on top of a sky- H MMW GA CAP AMERICA V. 3 HC H scraper, surrounded by dozens of well-armed men aiming for the kill…and our ‘heroes’ down DD BY MILLER JANSEN V. 1 TPB to one last bullet. The most exciting BODY BAGS story ever will definitely end with a bang! collects #9-12, $60 collects #158-172 & MORE, $30 H AST X-MEN V. 2 HC H NEW XMEN MORRION ULT V. 3 TPB Rock’N’Roll (1 shot) collects #13-24 & GS #1, $35 collects #142-154, $35 story FÁBIO MOON & GABRIEL BÁ art & cover FÁBIO MOON, GABRIEL BÁ, BRUNO H MYTHOS HC H XMEN 1ST CLASS BAND O’ BROS TP D’ANGELO & KAKO Romeo and Kelsie just want to go home, but life has other plans. -

September 2013

SEPTEMBER 2013: PREMIER PUBLISHERS HISTORY BOOKS Page 2-6 Page 10 INDEPENDENTS ONES TO WATCH Page 7 Page 10 NOVEL IDEAS BIFF’S BIT COMICS Page 8-9 Page 11 1 FOR $1: ABE SAPIEN #1 Mike Mignola | Scott Allie | Sebastian Fiumara NEW TITLES SHIPPING To celebrate the release of the new trade paperback collection, Dark Horse is offering Abe Sapien #1 again-for IN NOVEMBER: PREMIER $1! On the run from the B.P.R.D., a mutated Abe GHOST #1 Sapien traverses a devastated America, with monster corpses scattered around and cities Kelly Sue DeConnick | Christopher Sebela PUBLISHERS in ruin. Ghost, the hero trapped 1 FOR $1: between two worlds, STAR WARS DAWN STAR WARS LEGACY #1 fights to protect Chicago OF THE JEDI: Corinna Bechko | from extradimensional FORCE WAR #1 Gabriel Hardman demons disguised as John Ostrander | Dan Read the first chapter in humans. When a familiar Parsons | Jan Duursema the saga of Ania Solo- stranger destroys an el The fearsome Rakata Han and Leia’s great- train, Ghost makes a have invaded the Tython great-granddaughter- deal with a devil for the chance to uncover system, and war rages for only $1! She’s just her own mysterious past. The perfect issue on every world. With a girl trying to make to join this action-packed superhero title! Forcesabers in hand, her way in the galaxy, the Je’daii have aligned who comes into possession of a lightsaber NEVER ENDING #1 themselves with unlikely generals: Daegen and an Imperial communications droid-and (OF 3) (MR) Lok, the mad Je’daii, and the stranger, the discovers she has been targeted for death! Adam P. -

Pattern and Process Second Edition Monica G. Turner Robert H. Gardner

Monica G. Turner Robert H. Gardner Landscape Ecology in Theory and Practice Pattern and Process Second Edition L ANDSCAPE E COLOGY IN T HEORY AND P RACTICE M ONICA G . T URNER R OBERT H . G ARDNER LANDSCAPE ECOLOGY IN THEORY AND PRACTICE Pattern and Process Second Edition Monica G. Turner University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Zoology Madison , WI , USA Robert H. Gardner University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Frostburg, MD , USA ISBN 978-1-4939-2793-7 ISBN 978-1-4939-2794-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4939-2794-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015945952 Springer New York Heidelberg Dordrecht London © Springer-Verlag New York 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Pg. 107 Witchblade

Sample file WBTPBORv01_covers.indd 2 12/6/09 8:06 PM Witchblade created by: Marc Silvestri, David Wohl, Brian Haberlin and Michael Turner Sample file published by Top Cow Productions, Inc. Los Angeles WBTPBORv01_interiors.indd 1 12/6/09 7:49 PM Sample file WBTPBORv01_interiors.indd 2 12/6/09 7:49 PM Sample file WBTPBORv01_interiors.indd 3 12/6/09 7:49 PM For Top Cow Productions, Inc.: Marc Silvestri - Chief Executive Offi cer Matt Hawkins - President and Chief Operating Offi cer Filip Sablik - Publisher Rob Levin - VP - Editorial Mel Caylo - VP - Marketing & Sales Chaz Riggs - Graphic Design Phil Smith - Managing Editor Joshua Cozine - Assistant Editor Alyssa Phung - Controller Adrian Nicita - Webmaster Scott Newman - Production Assistant for image comics publisher: to fi nd the comic shop Erik Larsen nearest you call: executive director: 1-888-COMICBOOK ® Eric Stephenson letters for all issues in this edition by: Dennis Heisler Want more info? check out: www.topcow.com and www.topcowstore.com for news and exclusive Top Cow merchandise! For this edition For this edition Cover art by: Book Design and Layout by: Michael Turner, D-Tron Phil Smith and JD Smith Witchblade: Origins volume 1 Trade Paperback May 2008. FIRST PRINTING. ISBN: 978-1-58240-901-6 Published by Image Comics Inc. Offi ce of Publication: 1942 University Ave., Suite Sample305 Berkeley, CA 94704. $14.99 U.S.D.. Originally publishedfile in single magazine form as WITCHBLADE 1-8. Witchblade © 2008 Top Cow Productions, Inc. All rights reserved. “Witchblade,” the Witchblade logos, and the likeness of all characters (human or otherwise) featured herein are registered trademarks of Top Cow Productions, Inc. -

I Volume 1 | Issue 2 | September 2010

Volume 1 | Issue 2 | September 2010 i back cover table of contents next LAYOUT: INTERACTIVE DESIGN: Laurie Wilson, PAVMultimedia E-MAIL: [email protected] WWW.USAFA.EDU Volume 1 | Issue 2 | September 2010 ii back cover table of contents next Table of Contents Editorial: A Military Service Perspective Regarding the Integration of Character and Leadership Col Joseph E. Sanders and Lt Col Douglas R. Lindsay United States Air Force Academy page 3 Interview: Lt Gen Michael C. Gould, Superintendent of Cadets United States Air Force Academy page 7 Articles: Moral Development: The West Point Way Lt Col Michael E. Turner, Maj Chad W. DeBos and Lt Col (Ret) Francis C. Licameli United States Military Academy page 11 Honor and Character Capt Reed Bonadonna United States Merchant Marine Academy page 25 Leadership & Character at the United States Air Force Academy Lt Col (Ret) R. Jeffrey Jackson, Lt Col Douglas R. Lindsay and Maj Shane Coyne United States Air Force Academy page 37 Leadership Education and Development (LEAD) at the United States Naval Academy Capt Mark Adamshick United States Naval Academy page 51 Collaborating on Character…the SACCA Story Stephen A. Shambach and Dr. Robert J. Jackson United States Air Force Academy page 59 Interview: Dr. Ervin J. Rokke United States Air Force Academy page 67 Reflections: Developing Leaders of Character CMSgt John T. Salzman, Command Chief Master Sergeant United States Air Force Academy page 75 Becoming a Leader C1C Joshua Matthews United States Air Force Academy page 77 Volume 1 | Issue 2 | September 2010 1 back cover table of contents next Volume 1 | Issue 2 | September 2010 2 back cover table of contents next EDITORIAL A Military Service Perspective Regarding the Integration of Character and Leadership Douglas R. -

It Was Sheer Genius for the UK Firm Core Design to Create a Sleek

Gender and Videogames: the political valency of Lara Croft Maja Mikula, University of Technology Sydney The Face: Is Lara a feminist icon or a sexist fantasy? Toby Gard: Neither and a bit of both. Lara was designed to be a tough, self-reliant, intelligent woman. She confounds all the sexist cliches apart from the fact that she’s got an unbelievable figure. Strong, independent women are the perfect fantasy girls – the untouchable is always the most desirable. (Interview with Lara’s creator Toby Gard in The Face magazine, June 1997) Lara Croft is a fictional character: a widely popular videogame1 superwoman and recently also the protagonist of the blockbuster film Lara Croft: Tomb Raider (2001). Her body is excessively feminine - her breasts are massive and very pert, her waist is tiny, her hips are rounded and she wears extremely tight clothing. She is also physically strong, can fight and shoot, has incredible gymnastic abilities and is a best selling writer. Germaine Greer does not like Lara Croft. In her latest book, The Whole Woman (1999), Greer has unequivocally condemned the enforcement of artificial and oppressive ideals of femininity through pop icons such as the Barbie Doll. Lara Croft, whose ‘femaleness’ is clearly shaped by a desire to embody male sexual fantasies, is the antithesis of Greer’s ‘whole woman’; Greer calls her a: ‘sergeant-major with balloons stuffed up his shirt […] She’s a distorted, sexually ambiguous, male fantasy. Whatever these characters are, they’re not real women’ (Jones, 2001). 1 She may not be a 'real woman', but on the other hand Lara is clearly a 'positive image' for women, as Linda Artel and Susan Wengraf defined the term in 1976: The primary aim of [annotated guide] Positive Images was to evaluate media materials from a feminist perspective. -

Hearing on China's Shifting Economic Realities and Implications for the United States Hearing Before the U.S.-China Economic An

HEARING ON CHINA'S SHIFTING ECONOMIC REALITIES AND IMPLICATIONS FOR THE UNITED STATES HEARING BEFORE THE U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 24, 2016 Printed for use of the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: www.uscc.gov UNITED STATES-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION WASHINGTON: 2016 ii U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION HON. DENNIS C. SHEA, Chairman CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW, Vice Chairman Commissioners: PETER BROOKES HON. JAMES TALENT ROBIN CLEVELAND DR. KATHERINE C. TOB IN HON. BYRON L. DORGAN MICHAEL R. WESSEL JEFFREY L. FIEDLER DR. LARRY M. WORTZEL HON. CARTE P. GOODWIN MICHAEL R. DANIS, Executive Director The Commission was created on October 30, 2000 by the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act for 2001 § 1238, Public Law No. 106-398, 114 STAT. 1654A-334 (2000) (codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7002 (2001), as amended by the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for 2002 § 645 (regarding employment status of staff) & § 648 (regarding changing annual report due date from March to June), Public Law No. 107-67, 115 STAT. 514 (Nov. 12, 2001); as amended by Division P of the “Consolidated Appropriations Resolution, 2003,” Pub L. No. 108-7 (Feb. 20, 2003) (regarding Commission name change, terms of Commissioners, and responsibilities of the Commission); as amended by Public Law No. 109- 108 (H.R. 2862) (Nov. 22, 2005) (regarding responsibilities of Commission and applicability of FACA); as amended by Division J of the “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008,” Public Law Nol. -

Lijst 554 USD-DCD

$ DCD CODES!!!! LIST: FAX/MODEM/E-MAIL: may 24 2021 PREVIEWS DISK: may 26 2021 [email protected] for News, Specials and Reorders Visit WWW.PEPCOMICS.NL PEP COMICS DUE DATE: DCD WETH. DEN OUDESTRAAT 10 FAX: 24 mei 5706 ST HELMOND ONLINE: 24 mei TEL +31 (0)492-472760 SHIPPING: ($) FAX +31 (0)492-472761 juli/augustus #554 ********************************** DCD0060 Ordinary Gods #1 3.99 A *** DIAMOND COMIC DISTR. ******* DCD0061 [M] Cowl Principles/Pow TPB Vol.01 9.99 A ********************************** DCD0062 [M] Cowl The Greater Go TPB Vol.02 14.99 A DCD0063 [M] Dead Hand Cold War TPB Vol.01 16.99 A DCD SALES TOOLS page 026 DCD0064 [M] Hadrians Wall TPB 19.99 A DCD0001 Previews July 2021 #394 5.00 D DCD0065 Syphon (3) #1 3.99 A DCD0002 Marvel Previews J EXTRA Vol.05 #13 1.25 D DCD0066 [M] Chu #6 3.99 A DCD0003 Previews July 2021 Customer O #394 0.25 D DCD0067 [M] Chew TPB Vol.01 9.99 A DCD0004 Previews July 2021 Cust EXTRA #394 0.50 D DCD0068 [M] Chew International TPB Vol.02 12.99 A DCD0006 Previews July 2021 Reta EXTRA #394 2.08 D DCD0069 [M] Chew Just Desserts TPB Vol.03 12.99 A DCD0007 Game Trade Magazine #257 0.00 N DCD0070 [M] Chew Flambe TPB Vol.04 12.99 A DCD0008 Game Trade Magazine EXTRA #257 0.58 N DCD0071 [M] Chew Major League C TPB Vol.05 12.99 A IMAGE COMICS page 042 DCD0072 [M] Chew Space Cakes TPB Vol.06 14.99 A DCD0009 [M] Mom Mother/Madness A Ra (3) #1 5.99 A DCD0073 [M] Chew Bad Apples TPB Vol.07 12.99 A DCD0010 Blackbird TPB Vol.01 16.99 A DCD0074 [M] Chew Family Recipes TPB Vol.08 12.99 A DCD0011 Skyward My Low -

Guia Image Con Dibujos

Es La Hora De Las Tortas Guia De Escucha del Podcast Especial Image I Precalentamiento. * Ah, los orígenes. * Cuanto friqui reunido... * Los artículos de Image. * Cambalache. La Historia. * Dolmen 233. Ojo, este enlace va a una tienda. No es publicidad encubierta ni nos dan nada. * Enlaces para ir abriendo boca. * The Walking Dead. * Premios Eisner. Actualizados hasta 2006. Y aquí actualizado hasta 2014. Y por supuesto, su Web oficial. * Vertigo. * Toma pronunciación :-). * Epic Comics. * Malibú Comics. * Larry Stroman.Y el guionista.Y el cómic. Los Fundadores. * Todd McFarlane. * Erik Larsen. * Rob Liefeld. * Marc Silvestri. * Jim Lee. * Whilce Portacio. * Jim Valentino. Los estudios de Image. * Todd McFarlane Productions. * Highbrow Entertainment. * Extreme Studios. Luego Maximum Press. Y aún más luego Awesome comics. ;-). * Top Cow Productions. * Wildstorm Productions. De donde saldrán Homage, Clifhanger y ABC Comics. * ShadowLine. * Image Inc. * Skybound Entertainment. La “Edad Oscura”. * El Capitán América y sus Tet... * The Authority. * Michael Turner. * Cliffhanger. Títulos. * Scott Campbell. Y sus chicas ( y un Hellboy que no sabemos qué está haciendo ahí :-)). * Robert Kirkman. Y más. * Eric Stephenson. * E d Brubaker. * The Walking Dead. La serie de la tele. * Sobre la peli esa de chicos que cuidan vacas y seres venidos de otro planeta. * Brian Wood. * Rising Stars. * Sex Criminals. * El Manifiesto del Viejo Bastardo. * Terry Moore. No confundir :-). * The Image Revolution. * De anuncios, vaqueros y dibujantes. Las series. * Spawn. Spawn número 10. Las demandas. Sam and Twitch, de Bendis. Y las portadas, de Ashley Wood. Vertebreaker. Wanda. Y de la peli. Y alguna portada. Y de la serie animada, of course. * Sav age Dragon . -

Michael Turner, Michael Turner

http://www.dynamiteentertainment.com/cgi-bin/solicitations.pl 1. MERCENARIES #1 Price: $3.99 Rating: Teen+ Covers: Michael Turner, Michael Turner - 50/50 Connecting Covers! Writer: Brian Reed Penciller: Edgar Salazar Colorist: TBD Genre: ACTION/ADVENTURE Awards: None Publication Date: OCTOBER, 2007 Format: Comic Book Rights: WW Age range: 13-24 The best-selling video game from Pandemic Studios is the next new DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT comic book event! Get ready to join up with the MERCENARIES! Mercenaries the game has revolutionized the world of 3rd-person action-shooters by putting players in the middle of real world combat with the kind of freedom only a mercenary has. And now DYNAMITE'S MERCENARIES places you in the middle of the action! Featuring two connecting pieces of cover art by red-hot artist Michael Turner, a stellar script from Mercenaries writer Brian (Ms. Marvel, Red Sonja) Reed and art from Dynamite up-n-comer Edgar Salazar, MERCENARIES #1 puts you into the middle of the Mercenaries next adventure. Retailer Incentives: #1 FOR EVERY 15 COPIES ORDERED AND RECEIVED, RETAILERS WILL RECEIVE A TURNER VIRGIN COVER AT NET COST. #2 FOR EVERY 35 COPIES ORDERED AND RECEIVED, RETAILERS WILL RECEIVE A TURNER SKETCH COVER AT NET COST. http://www.dynamiteentertainment.com/cgi-bin/solicitations.pl (1 of 21) [7/20/2007 5:18:27 PM] http://www.dynamiteentertainment.com/cgi-bin/solicitations.pl 2. MERCENARIES #1 - FOIL COVER Price: $29.99 The best-selling video game from Pandemic Studios is the next new DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT comic book event! Get ready to join up with the MERCENARIES! Mercenaries the game has revolutionized the world of 3rd- person action-shooters by putting players in the middle of real world combat with the kind of freedom only a mercenary has. -

While Investigating a Series of Murders, New

While investigating a series of murders, New York City Police Detective Sara Pezzini is drawn to a mysterious “Tournament” at the abandoned Rialto Theatre where criminals are vying to posess a powerful weapon. On that fateful night, Pezzini’s life is forever changed when she becomes the latest in a line of female bearers of an ancient and mystical artifct – The Witchblade. Go back to the beginning and discover Sara’s first encounters with the Witchblade gauntlet, Kenneth Irons, Jackie Estacado, and Ian Nottingham. The Witchblade Collected Edition includes the first 19 issues, the first 4 issues of Tales of the Witchblade, as well as The Darkness Family Ties crossover issues 9 and 10. 1 $29.99 US ISBN: 978-1-5343-1564-8 SUPERHERO RATED MSample / MATURE file Witchblade Created by Marc Silvestri, David Wohl, Brian Haberlin, and Michael Turner Sample file Published by Top Cow Productions, Inc. Los Angeles Cover art by Michael Turner First edition book design and layout by Vincent Valentine For Top Cow Productions, Inc. Marc Silvestri - CEO Matt Hawkins - President & COO Elena Salcedo - Vice President of Operations Sample file Vincent Valentine - Lead Production Artist Henry Barajas - Director of Operations Dylan Gray - Marketing Director Production by Tricia Ramos IMAGE COMICS, INC. • Robert Kirkman: Chief Operating Officer • Erik Larsen: Chief Financial Officer • Todd McFarlane: President • Marc Silvestri: Chief Executive Officer • Jim Valentino: Vice President • Eric Stephenson: Publisher / Chief Creative Officer • Jeff Boison: Director of Publishing Planning & Book Trade Sales • Chris Ross: Director of Digital Services • Jeff Stang: Director of Direct Market Sales • Kat Salazar: Director of PR & Marketing • Drew Gill: Cover Editor • Heather Doornink: Production Director • Nicole Lapalme: Controller • IMAGECOMICS.COM THE COMPLETE WITCHBLADE, VOL.