Intansuwandi-Backtoproduction.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JSSE Journal of Social Science Education

Journal of Social Science JSSE Education The Beutelsbach Consensus Sibylle Reinhardt “...not simply say that they are all Nazis.” Controversy in Discussions of Current Topics in German Civics Classes David Jahr, Christopher Hempel, Marcus Heinz Teaching for Transformative Experiences in History: Experiencing Controversial History Ideas Marc D. Alongi, Benjamin C. Heddy, Gale M. Sinatra Argument, Counterargument, and Integration? Patterns of Argument Reappraisal in Controversial Classroom Discussions Dorothee Gronostay Teachers’ Stories of Engaging Students in Controversial Action Projects on the Island of Ireland Majella McSharry, Mella Cusack Globalization as Continuing Colonialism – Critical Global Citizenship Education in an Unequal World Pia Mikander Turkish Social Studies Teachers’ Thoughts About the Teaching of Controversial Issues Ahmet Copur, Muammer Demirel Human Rights Education in Israel: Four Types of Good Citizenship Ayman Kamel Agbaria, Revital Katz-Pade Report on the Present Trainer Training Course of the Pestalozzi Programme (Council of Europe) “Evaluation of Transversal Attitudes, Skills and Knowledge” (Module A) Bernt Gebauer Journal of Social Science Education Volume 15, Number 2, Summer 2016 ISSN 1618–5293 Masthead Editors: Reinhold Hedtke, Bielefeld University, Faculty of Sociology Ian Davies, Department of Educational Studies, University of York Andreas Fischer, Leuphana University Lüneburg, Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences Tilman Grammes, University of Hamburg, Faculty of Educational Science Isabel Menezes, -

Imperialism & the Globalisation of Production

Imperialism & the Globalisation of Production The Earth at Night— Reverse image of satellite photos* “Instead of the conservative motto, ‘a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work!’ [...] the revolutionary watchword, ‘abolition of the wages * system!” PhD thesis John Smith, University of Sheffield, July 2010 *Karl Marx, 1865, Value, Price and Profit 1 Please contact the author with any comments, criticisms etc, at [email protected] Word Count footnotes Abstract 300 Chapter 1 18952 4635 Chapter 2 15054 3118 Chapter 3 16298 2874 Chapter 4 8747 1623 Chapter 5 11560 1352 Chapter 6 8042 1417 Chapter 7 12307 2347 Conclusion 4110 1326 Total 95370 18692 2 Contents Glossary 6 Figures and Tables 6 Acknowledgements 9 Abstract 11 Chapter 1— Globalisation and ‘New’ Imperialism 13 1.1 Neoliberal globalisation and the persistence of the North-South divide 14 Core concepts.....................................................................................................15 Theoretical development of concepts: Neoliberal globalisation—a new stage in capitalism's imperialist development.........................................................................................20 Thesis scope and research strategy ............................................................................25 1.2 Making exploitation invisible ...................................................................................29 Exploitation and super-exploitation...........................................................................31 What is the economists’ theoretical -

The Core of the Apple: Dark Value and Degrees of Monopoly in Global Commodity Chains

The Core of the Apple: Dark Value and Degrees of Monopoly in Global Commodity Chains Donald A. Clelland1 University of Tennessee (Emeritus) [email protected] Abstract The capitalist world-economy takes the form of an iceberg. The most studied part which appears above the surface is supported by a huge underlying structure that is out of sight. Unlike the iceberg, the world-economy is a dynamic system based on flows of value from the underside toward the top. These include drains of surplus (expropriated value) that take two forms: visible monetarized flows of bright value and hidden un(der)costed flows that carry dark value (the unrecorded value of cheap labor, labor reproduction and ecological externalities). Commodity chains are central mechanisms for these surplus drains in the world-economy. At each node of the chain, participants attempt to maximize their capture of bright value through wages, rent and profit. They do this by constructing differential degrees of monopoly (control of the markup between cost and sale price) and degrees of monopsony (control of markdowns of production costs). However, this process depends upon the transformation of dark value into bright value for capture. Via an examination of the Apple iPad commodity chain, I show how the bright value captured by Apple depends on the dark value extracted by its suppliers. Dark value is estimated by measurements of the value of under-payments for wage labor, reproductive labor and environmental damage in Asian countries, especially China. Surprisingly, most dark value embedded in the iPad is captured by final buyers (mostly in the core) as consumer surplus. -

Prosperity Undermined

Prosperity Undermined The Status Quo Trade Model’s 21-Year Record of Massive U.S. Trade Deficits, Job Loss and Wage Suppression www.tradewatch.org August 2015 Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch Published August 2015 by Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch Public Citizen is a national, nonprofit consumer advocacy organization that serves as the people's voice in the nation's capital. Since our founding in 1971, we have delved into an array of areas, but our work on each issue shares an overarching goal: To ensure that all citizens are represented in the halls of power. For four decades, we have proudly championed citizen interests before Congress, the executive branch agencies and the courts. We have successfully challenged the abusive practices of the pharmaceutical, nuclear and automobile industries, and many others. We are leading the charge against undemocratic trade agreements that advance the interests of mega- corporations at the expense of citizens worldwide. As the federal government wrestles with critical issues – fallout from the global economic crisis, health care reform, climate change and so much more – Public Citizen is needed now more than ever. We are the countervailing force to corporate power. We fight on behalf of all Americans – to make sure your government works for you. We have five policy groups: our Congress Watch division, the Energy Program, Global Trade Watch, the Health Research Group and our Litigation Group. Public Citizen is a nonprofit organization that does not participate in partisan political activities or endorse any candidates for elected office. We accept no government or corporate money – we rely solely on foundation grants, publication sales and support from our 300,000 members. -

The Social Question in the Twenty-First Century:A Global View

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The Social Question in the Twenty-First Century A Global View Breman, J.; Harris, K.; Lee, C.K.; van der Linden, M. DOI 10.1525/luminos.74 Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Breman, J., Harris, K., Lee, C. K., & van der Linden, M. (Eds.) (2019). The Social Question in the Twenty-First Century: A Global View. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.74 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:10 Oct 2021 Luminos is the Open Access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. -

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY of GLOBAL LABOR ARBITRAGE Raúl

Revista Problemas del Desarrollo Volume 46, Number 183, October-December 2015 http://www.scielo.org.mx/ THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF GLOBAL LABOR ARBITRAGE Raúl Delgado Wise, David Martin 1 Date received: February 9, 2015. Date accepted: June 15, 2015 Abstract This paper analyzes the fundamental role of wage differences in the efforts undertaken by major multinational corporations to restructure their productive, trade, financial, and service strategies under the aegis of neoliberal globalization. We are especially interested in underscoring the way in which these disparities, by means of geographic relocation and the redistribution of productive processes, have become an easily accessible and apparently inexhaustible source of extraordinary earnings. This situation has given rise to the entrenchment of unequal development between central and peripheral countries and a new international division of labor characterized by the direct and indirect exportation of the most valuable commodity for capital: the labor force. Keywords: Labor arbitrage, wages, productive restructuring, labor force, capital-labor. INTRODUCTION The global labor arbitrage2 strategy currently favored by major multinational corporations has become a key factor in the restructuring of the international political economy. The neoliberal age has ushered in a new phase in the history of contemporary capitalism and imperialist rule, based on the exploitation of a cheap and flexible workforce, primarily based in peripheral countries. We therefore posit that monopolistic capital -

Economics Perils of a Different Globalization

MORGAN STANLEY EQUITY RESEARCH March 22, 2006 Investment Perspectives — US and the Americas Strategy and Economics March 20, 2006 into a segment of the global labor market that has never really known the meaning of job anxiety and stress. Blue- Economics collar workers in factories have, of course, long been on the Perils of a Different Globalization front line in facing the ups and downs of business cycles, as well as the intensification of global pressures. By contrast, Morgan Stanley & Co. Stephen S. Roach white-collar workers in services-based enterprises have not. Incorporated [email protected] That is now changing. The rules of engagement on the bat- tleground of globalization are being rewritten. The services Economics and politics are on a dangerous collision course. economy is now on the leading edge of feeling the stresses As the forces of globalization strengthen, the drumbeat of and strains of an increasingly competitive and open world protectionism is growing louder. Made in France, the Euro- economy. pean strain of protectionism reflects a newfound nationalism that strikes at the heart of pan-regional integration. Made in This is a truly extraordinary development in the continuum of America and exacerbated by fear of the “China factor,” a economic history. Economists have long dubbed services as different strain of protectionism plays to the angst of middle- “nontradables” — underscoring the time-honored proposition class US wage earners. that service providers had to be in close proximity with their customers to offer in-person delivery of expertise, advice, or Whether the threat is perceived to be from the inside (as it is assistance. -

GLOBAL TRENDS: PARADOX of PROGRESS Feedback from Over 2,500 People Around the World from All Walks of Life

GLOBAL TRENDS PARADOX OF PROGRESS A publication of the National Intelligence Council JANUARY 2017 NIC 2017-001 ISBN 978-0-16-093614-2 To view electronic version: www.dni.gov/nic/globaltrends TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter From the Chairman of the vi National Intelligence Council ix The Future Summarized 1 The Map of the Future 5 Trends Transforming the Global Landscape 29 Near Future: Tensions Are Rising Three Scenarios for the Distant Future: 45 Islands, Orbits, Communities What the Scenarios Teach Us: Fostering 63 Opportunities Through Resilience 70 Methodological Note 72 Glossary 74 Acknowledgements ANNEXES 85 The Next Five Years by Region 159 Key Global Trends v Letter from the Chairman of the National LetterIntelligence from the Council Chairman of the National Intelligence Council OF N R A O TI T C O E N R A I L D I N E T H E T L F L I O G E E C N I C F F E O Thinking about the future is vital but hard. Crises keep intruding, making it all but impossible to look beyond daily headlines to what lies over the horizon. In those circumstances, thinking “outside the box,” to use the cliché, too often loses out to keeping up with the inbox. That is why every four years the National Intelligence Council (NIC) undertakes a major assessment of the forces and choices shaping the world before us over the next two decades. This version, the sixth in the series, is titled, “Global Trends: The Paradox of Progress,” and we are proud of it. -

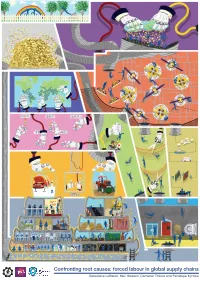

Confronting Root Causes: Forced Labour in Global Supply Chains

Confronting root causes: forced labour in global supply chains Genevieve LeBaron, Neil Howard, Cameron Thibos and Penelope Kyritsis Confronting root causes: forced labour in global supply chains Genevieve LeBaron, Neil Howard, Cameron Thibos and Penelope Kyritsis This collection was published in 2018 by openDemocracy and the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI), University of Sheffield under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 licence. Publication layout and design: Cameron Thibos Illustrations: Carys Boughton (www.carysboughton.com) ABOUT BTS Beyond Trafficking and Slavery (BTS) is an independent marketplace of ideas that uses evidence-based advocacy to tackle the political, economic, and social root causes of global exploitation, vulnerability and forced labour. It provides original analysis and specialised knowledge on these issues with the rigour of academic scholarship, the clarity of journalism, and the immediacy of political activism. BTS is housed within openDemocracy, a UK-based digital commons dedicated to converting trailblazing thinking into lasting, meaningful change. ABOUT SPERI The Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI) at the University of Sheffield brings together leading international researchers, policy-makers, journalists and opinion formers to develop new ways of thinking about the economic and political challenges formed by the current combination of financial crisis, shifting economic power and environmental threat. SPERI’s goal is to shape and lead the debate on how to build a sustainable recovery and a sustainable political economy for the long-term. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Genevieve LeBaron is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Politics at the University of Sheffield, Chair of the Yale University Working Group on Modern Slavery, and a UK ESRC Future Research Leaders Fellow. -

Globalization, Employment, and Economic Development: a Briefing Paper

June 23, 2004 Globalization, Employment, and Economic Development: A Briefing Paper Gary Gereffi (Duke University) Timothy J. Sturgeon (Industrial Performance Center, MIT) Sloan Workshop Series in Industry Studies Rockport, Massachusetts, June 14-16, 2004 The Great Global Job Shift A cover story in the February 3, 2003 issue of Business Week highlighted the impact of global outsourcing over the past several decades on the quality and quantity of jobs in both developed and developing countries (Engardio, Bernstein, and Kripalani, 2003). The first wave of global outsourcing began in the 1960s and 1970s with the exodus of production jobs in shoes, clothing, cheap electronics, and toys. After that, routine service work, like credit-card receipt processing, airline reservations, and the writing of basic software code began to move offshore. Today, the computerization of work, the Internet, and high-speed private data networks have allowed a wide range of “knowledge work” to become more footloose. Global outsourcing reveals many of the key features of contemporary globalization: it deals with international competitiveness in a way that underscores the growing interdependence of developed and developing countries; a huge part of the debate centers around jobs, wages, and skills in different parts of the world; and there is a useful focus on how the chain of activities is organized across firms and country boundaries, and where in the chain value and employment is created. There are enormous political as well as economic stakes in how global outsourcing plays itself out in the coming years, particularly as well-endowed and strategically positioned economies increase their participation in global value chains. -

Confronting Root Causes: Forced Labour in Global Supply Chains

Confronting root causes: forced labour in global supply chains Genevieve LeBaron, Neil Howard, Cameron Thibos and Penelope Kyritsis Confronting root causes: forced labour in global supply chains Genevieve LeBaron, Neil Howard, Cameron !ibos and Penelope Kyritsis This collection was published in 2018 by openDemocracy and the She!eld Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI), University of She!eld under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 licence. Publication layout and design: Cameron Thibos Illustrations: Carys Boughton (www.carysboughton.com) ABOUT BTS Beyond Tra!cking and Slavery (BTS) is an independent marketplace of ideas that uses evidence-based advocacy to tackle the political, economic, and social root causes of global exploitation, vulnerability and forced labour. It provides original analysis and specialised knowledge on these issues with the rigour of academic scholarship, the clarity of journalism, and the immediacy of political activism. BTS is housed within openDemocracy, a UK-based digital commons dedicated to converting trailblazing thinking into lasting, meaningful change. ABOUT SPERI The She!eld Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI) at the University of She!eld brings together leading international researchers, policy-makers, journalists and opinion formers to develop new ways of thinking about the economic and political challenges formed by the current combination of "nancial crisis, shifting economic power and environmental threat. SPERI’s goal is to shape and lead the debate on how to build a sustainable recovery and a sustainable political economy for the long-term. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Genevieve LeBaron is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Politics at the University of She!eld, Chair of the Yale University Working Group on Modern Slavery, and a UK ESRC Future Research Leaders Fellow. -

The Jobs Question by Paul Craig Roberts Published August 1, 2004

The Washington Times www.washingtontimes.com The jobs question By Paul Craig Roberts Published August 1, 2004 In the current economic recovery, low-pay, low-skill jobs account for twice the normal job growth, reports Stephen Roach, chief economist for Morgan Stanley (New York Times, July 22). Mr. Roach attributes the low quality of new U.S. jobs to globalization: "Under unrelenting pressure to cut costs, American companies are now replacing high-wage workers here with like quality, low-wage workers abroad. With new information technologies allowing products and now knowledge-based services to flow more easily cross borders, global labor arbitrage is likely to be an enduring feature of the economy. What are we going to do about it?," he asks. So long as most economists and elected officials remain in total denial, we are unlikely to do anything about it. Desirous of demonstrating globalization is creating more U.S. jobs than it is destroying, normally sound economists are making fundamental analytical and empirical errors. For example, Matthew J. Slaughter, a professor at Dartmouth, recently concluded that over 1991-2001, "For every one job that U.S. multinationals created abroad in their foreign affiliates they created nearly two U.S. jobs in their parent operations." This would be good news, if true. Unfortunately, in measuring the growth of U.S. multinational employment Mr. Slaughter did not take into account the two biggest forces driving multinational employment during that period. Multinational employment grew because multinationals acquired many existing smaller firms and many firms became multinational by establishing foreign operations for the first time.