Determinants of the Zambian Kwacha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Measurement of Zimbabwe's Hyperinflation

18485_CATO-R2(pps.):Layout 1 8/7/09 3:55 PM Page 353 On the Measurement of Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation Steve H. Hanke and Alex K. F. Kwok Zimbabwe experienced the first hyperinflation of the 21st centu- ry.1 The government terminated the reporting of official inflation sta- tistics, however, prior to the final explosive months of Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation. We demonstrate that standard economic theory can be applied to overcome this apparent insurmountable data problem. In consequence, we are able to produce the only reliable record of the second highest inflation in world history. The Rogues’ Gallery Hyperinflations have never occurred when a commodity served as money or when paper money was convertible into a commodity. The curse of hyperinflation has only reared its ugly head when the supply of money had no natural constraints and was governed by a discre- tionary paper money standard. The first hyperinflation was recorded during the French Revolution, when the monthly inflation rate peaked at 143 percent in December 1795 (Bernholz 2003: 67). More than a century elapsed before another hyperinflation occurred. Not coincidentally, the inter- Cato Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009). Copyright © Cato Institute. All rights reserved. Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics at The Johns Hopkins University and a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. Alex K. F. Kwok is a Research Associate at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise at The Johns Hopkins University. 1In this article, we adopt Phillip Cagan’s (1956) definition of hyperinflation: a price level increase of at least 50 percent per month. -

Country Codes and Currency Codes in Research Datasets Technical Report 2020-01

Country codes and currency codes in research datasets Technical Report 2020-01 Technical Report: version 1 Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre Harald Stahl Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 2 Abstract We describe the country and currency codes provided in research datasets. Keywords: country, currency, iso-3166, iso-4217 Technical Report: version 1 DOI: 10.12757/BBk.CountryCodes.01.01 Citation: Stahl, H. (2020). Country codes and currency codes in research datasets: Technical Report 2020-01 – Deutsche Bundesbank, Research Data and Service Centre. 3 Contents Special cases ......................................... 4 1 Appendix: Alpha code .................................. 6 1.1 Countries sorted by code . 6 1.2 Countries sorted by description . 11 1.3 Currencies sorted by code . 17 1.4 Currencies sorted by descriptio . 23 2 Appendix: previous numeric code ............................ 30 2.1 Countries numeric by code . 30 2.2 Countries by description . 35 Deutsche Bundesbank Research Data and Service Centre 4 Special cases From 2020 on research datasets shall provide ISO-3166 two-letter code. However, there are addi- tional codes beginning with ‘X’ that are requested by the European Commission for some statistics and the breakdown of countries may vary between datasets. For bank related data it is import- ant to have separate data for Guernsey, Jersey and Isle of Man, whereas researchers of the real economy have an interest in small territories like Ceuta and Melilla that are not always covered by ISO-3166. Countries that are treated differently in different statistics are described below. These are – United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland – France – Spain – Former Yugoslavia – Serbia United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. -

On the Measurement of Zimbabwe's Hyperinflation

18485_CATO-R2(pps.):Layout 1 8/7/09 3:55 PM Page 353 On the Measurement of Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation Steve H. Hanke and Alex K. F. Kwok Zimbabwe experienced the first hyperinflation of the 21st centu - ry. 1 The government terminated the reporting of official inflation sta - tistics, however, prior to the final explosive months of Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation. We demonstrate that standard economic theory can be applied to overcome this apparent insurmountable data problem. In consequence, we are able to produce the only reliable record of the second highest inflation in world history. The Rogues’ Gallery Hyperinflations have never occurred when a commodity served as money or when paper money was convertible into a commodity. The curse of hyperinflation has only reared its ugly head when the supply of money had no natural constraints and was governed by a discre - tionary paper money standard. The first hyperinflation was recorded during the French Revolution, when the monthly inflation rate peaked at 143 percent in December 1795 (Bernholz 2003: 67). More than a century elapsed before another hyperinflation occurred. Not coincidentally, the inter- Cato Journal, Vol. 29, No. 2 (Spring/Summer 2009). Copyright © Cato Institute. All rights reserved. Steve H. Hanke is a Professor of Applied Economics at The Johns Hopkins University and a Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. Alex K. F. Kwok is a Research Associate at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise at The Johns Hopkins University. 1In this article, we adopt Phillip Cagan’s (1956) definition of hyperinflation: a price level increase of at least 50 percent per month. -

Southern Africa Region: Market Watch

Southern Africa Region: Market Watch Johannesburg Regional Bureau | March 2021 Issue #5 GLOBAL MARKET INFORMATION The FAO Food Price Index averaged 116 points in February 2021, 2.8 points higher than in January, marking the 9th month of consecutive rise and reaching its highest level since July 2014. The February increase was led by strong gains in the sugar and vegetable oils sub-indices, while those of cereals, dairy and meat also rose but by a lesser extent. The FAO Cereal Price Index averaged 125.7 points in February, up 1.5 points from January and 26.3 points above its February 2020 level. Among major coarse grains, international sorghum prices increased the most. International maize prices also rose, albeit by only 0.9 percent from the previous month. Maize export prices in February were up 45.5 percent from the previous year, underpinned by continued strong import demand amidst shrinking export supplies. International rice prices also edged up some more, driven by demand for lower quality Indica and Japonica rice. Source: FAO 2 SOUTH AFRICA South Africa’s maize prices remain 1 2 above average and this will affect countries that rely on it for maize imports. The South African rand has continued to strengthen against the USD in recent months (1), but since October 2020, food inflation has remained slightly elevated at 3 above 5% due to higher grain prices (2). South Africa’s maize prices took a sharp upward turn in mid-2020 and remain at above average levels (3). In February 2021 it was 8% above the 5 year average (5YA) and 17% above year prior levels. -

WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates

The WM/Refinitiv Closing Spot Rates The WM/Refinitiv Closing Exchange Rates are available on Eikon via monitor pages or RICs. To access the index page, type WMRSPOT01 and <Return> For access to the RICs, please use the following generic codes :- USDxxxFIXz=WM Use M for mid rate or omit for bid / ask rates Use USD, EUR, GBP or CHF xxx can be any of the following currencies :- Albania Lek ALL Austrian Schilling ATS Belarus Ruble BYN Belgian Franc BEF Bosnia Herzegovina Mark BAM Bulgarian Lev BGN Croatian Kuna HRK Cyprus Pound CYP Czech Koruna CZK Danish Krone DKK Estonian Kroon EEK Ecu XEU Euro EUR Finnish Markka FIM French Franc FRF Deutsche Mark DEM Greek Drachma GRD Hungarian Forint HUF Iceland Krona ISK Irish Punt IEP Italian Lira ITL Latvian Lat LVL Lithuanian Litas LTL Luxembourg Franc LUF Macedonia Denar MKD Maltese Lira MTL Moldova Leu MDL Dutch Guilder NLG Norwegian Krone NOK Polish Zloty PLN Portugese Escudo PTE Romanian Leu RON Russian Rouble RUB Slovakian Koruna SKK Slovenian Tolar SIT Spanish Peseta ESP Sterling GBP Swedish Krona SEK Swiss Franc CHF New Turkish Lira TRY Ukraine Hryvnia UAH Serbian Dinar RSD Special Drawing Rights XDR Algerian Dinar DZD Angola Kwanza AOA Bahrain Dinar BHD Botswana Pula BWP Burundi Franc BIF Central African Franc XAF Comoros Franc KMF Congo Democratic Rep. Franc CDF Cote D’Ivorie Franc XOF Egyptian Pound EGP Ethiopia Birr ETB Gambian Dalasi GMD Ghana Cedi GHS Guinea Franc GNF Israeli Shekel ILS Jordanian Dinar JOD Kenyan Schilling KES Kuwaiti Dinar KWD Lebanese Pound LBP Lesotho Loti LSL Malagasy -

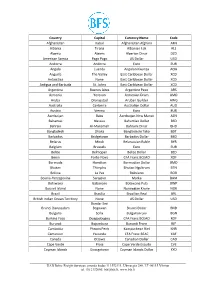

International Currency Codes

Country Capital Currency Name Code Afghanistan Kabul Afghanistan Afghani AFN Albania Tirana Albanian Lek ALL Algeria Algiers Algerian Dinar DZD American Samoa Pago Pago US Dollar USD Andorra Andorra Euro EUR Angola Luanda Angolan Kwanza AOA Anguilla The Valley East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antarctica None East Caribbean Dollar XCD Antigua and Barbuda St. Johns East Caribbean Dollar XCD Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine Peso ARS Armenia Yerevan Armenian Dram AMD Aruba Oranjestad Aruban Guilder AWG Australia Canberra Australian Dollar AUD Austria Vienna Euro EUR Azerbaijan Baku Azerbaijan New Manat AZN Bahamas Nassau Bahamian Dollar BSD Bahrain Al-Manamah Bahraini Dinar BHD Bangladesh Dhaka Bangladeshi Taka BDT Barbados Bridgetown Barbados Dollar BBD Belarus Minsk Belarussian Ruble BYR Belgium Brussels Euro EUR Belize Belmopan Belize Dollar BZD Benin Porto-Novo CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Bermuda Hamilton Bermudian Dollar BMD Bhutan Thimphu Bhutan Ngultrum BTN Bolivia La Paz Boliviano BOB Bosnia-Herzegovina Sarajevo Marka BAM Botswana Gaborone Botswana Pula BWP Bouvet Island None Norwegian Krone NOK Brazil Brasilia Brazilian Real BRL British Indian Ocean Territory None US Dollar USD Bandar Seri Brunei Darussalam Begawan Brunei Dollar BND Bulgaria Sofia Bulgarian Lev BGN Burkina Faso Ouagadougou CFA Franc BCEAO XOF Burundi Bujumbura Burundi Franc BIF Cambodia Phnom Penh Kampuchean Riel KHR Cameroon Yaounde CFA Franc BEAC XAF Canada Ottawa Canadian Dollar CAD Cape Verde Praia Cape Verde Escudo CVE Cayman Islands Georgetown Cayman Islands Dollar KYD _____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Nigerian Naira, Kenyan Shilling and Zambian Kwacha

360 Madison Ave., 17th fl. New York, NY 10017 646 289-5410 ISDA, INC., EMTA AND THE FOREIGN EXCHANGE COMMITTEE ANNOUNCE AMENDED RATE SOURCE DEFINITIONS FOR THE NIGERIAN NAIRA, KENYAN SHILLING AND ZAMBIAN KWACHA May 28, 2015. ISDA, Inc., EMTA and the Foreign Exchange Committee today jointly announced amendments to Annex A of the 1998 FX and Currency Option Definitions (the “1998 Definitions”) to amend certain rate source definitions. Effective May 28, 2015, Annex A is hereby amended to replace Sections 4.5(d)(v)(A), 4.5(d)(vii)(A) and 4.5(d)(viii)(A), each in their entirety, with the following: (d) Middle East/Africa. (v) Nigerian Naira. (A) “NGN FMDA” or “NGN01” each means that the Spot Rate for a Rate Calculation Date will be the arithmetic average of the Nigerian Naira/US Dollar bid and offer rates, expressed as the amount of Nigerian Naira per one US Dollar, for settlement in two Business Days, reported by the Financial Market Dealers Association of Nigeria, which is published at www.fmdqotc.com under the caption NIFEX by not later than 10:00 a.m., Lagos time, on the first Business Day following that Rate Calculation Date. (vii) Kenyan Shilling. (A) “KES Thomson Reuters” or “KES01” each means that the Spot Rate for a Rate Calculation Date will be the Kenyan Shilling/U.S. Dollar spot rate, expressed as the amount of Kenyan Shilling per one U.S. Dollar, for settlement in two Business Days, reported by Thomson Reuters and published on Thomson Reuters Screen KESFIX=TR Page not later than 12:00 p.m., Nairobi time, on that Rate Calculation Date. -

PDF External Sector Statistics ISO Country Codes

External Sector Statistics (ESS) System - Submission of International Transactions Page 285 of 300 and External Position Information APPENDIX 8 STANDARD CODES Appendix 8(a) List of Country and Currency Codes ISO Country and Currency Codes* Country Code Currency Code AFGHANISTAN AF Afghani AFN ÅLAND ISLANDS AX Euro EUR ALBANIA AL Lek ALL ALGERIA DZ Algerian Dinar DZD AMERICAN SAMOA AS US Dollar USD ANDORRA AD Euro EUR ANGOLA AO Kwanza AOA ANGUILLA AI East Caribbean Dollar XCD ANTARCTICA AQ No universal currency ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA AG East Caribbean Dollar XCD ARGENTINA AR Argentine Peso ARS ARMENIA AM Armenian Dram AMD ARUBA AW Aruban Florin AWG AUSTRALIA AU Australian Dollar AUD AUSTRIA AT Euro EUR AZERBAIJAN AZ Azerbaijanian Manat AZN BAHAMAS BS Bahamian Dollar BSD BAHRAIN BH Bahraini Dinar BHD BANGLADESH BD Taka BDT BARBADOS BB Barbados Dollar BBD BELARUS BY Belarussian Ruble BYR BELGIUM BE Euro EUR BELIZE BZ Belize Dollar BZD BENIN BJ CFA Franc BCEAO XOF BERMUDA BM Bermudian Dollar BMD BHUTAN BT Ngultrum BTN BHUTAN BT Indian Rupee INR BOLIVIA, PLURINATIONAL STATE OF BO Boliviano BOB BOLIVIA, PLURINATIONAL STATE OF BO Mvdol BOV BONAIRE, SINT EUSTATIUS AND SABA BQ US Dollar USD BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA BA Convertible Mark BAM BOTSWANA BW Pula BWP BOUVET ISLAND BV Norwegian Krone NOK BRAZIL BR Brazilian Real BRL BRITISH INDIAN OCEAN TERRITORY IO US Dollar USD BRUNEI DARUSSALAM BN Brunei Dollar BND BULGARIA BG Bulgarian Lev BGN BURKINA FASO BF CFA Franc BCEAO XOF BURUNDI BI Burundi Franc BIF CAMBODIA KH Riel KHR CAMEROON CM CFA Franc BEAC -

Co-Operation Between the European Union and the Republic of Zambia

Version 25 Sep 2007 Co-operation between The European Union and The Republic of Zambia Joint Annual Report1 2006 Annual report on the implementation of the ACP-EU Conventions and other co- operation activities 1 Prepared jointly by the NAO and the Head of Delegation on the basis of the Annex 4, Article 5 of the Cotonou Partnership Agreement 1 Version 25 Sep 2007 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS: ABC African Banking Corporation ACIS Advance Cargo Information System ACP African, Caribbean, Pacific Group of States ADB African Development Bank AGOA African Growth and Opportunity Act AIDS Acquired Immuned Deficiency Syndrome ARSO African Regional Standards Organisation ARVs Anti-Retroviral Drugs ASIP Agricultural Sector Investment Programme ASS African Sub-Saharan zone ATI African Trade Insurance AU African Union AWP Annual Work Plan BIS Backbone Information System BoP Balance of Payment BESSIP Basic Education Sub-Sector Programme BoZ Bank of Zambia BWI Bretton Woods Institutions CARITAS Catholic Health Initiatives CAFOD Catholic Fund for Overseas Development CBoH Central Board of Health CDE Centre for the Development of Entreprise CLA Community Livestock Auxiliaries COMESA Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa CP Cooperating Partners CRS Catholic Relief Service CSP Country Support Paper DANIDA Danish International Development Authority DFID Department for International Development DNR Department of National Registration DRC Democratic Republic of Congo EBZ Export Board of Zambia EC European Commission ECHO European Commission Humanitarian Aid -

Salary Scales for Africa

Africa Click on the country name to be directed to its salary scale. Angola . 03 Central African Republic . 10 Ethiopia . 17 Benin . 04 Chad . 11 Gabon . 18 Botswana . 05 Comoros . 12 Gambia . 19 Burkina Faso . 06 Congo . 13 Ghana . 20 Burundi . 07 Cote D’Ivoire . 14 Guinea-Bissau . 21 Cameroon . 08 Democratic Republic of Congo . 15 Guinea . 22 Cape Verde . 09 Equatorial Guinea . 16 Kenya . 23 1 Africa Click on the country name to be directed to its salary scale. Lesotho . 24 Niger . 32 Sudan . 40 Liberia . 25 Nigeria . 33 Tanzania . 41 Madagascar . 26 Rwanda . 34 Togo . 42 Malawi . 27 Sao Tome et Principe . 35 Uganda . 43 Mali . 28 Senegal . 36 Zambia . 44 Mauritania . 29 Sierra Leone . 37 Zimbabwe . 45 Mauritius . 30 South Africa . 38 Mozambique . 31 South Sudan . 39 2 FY22 Net Salary Scales, Angola Effective Date Region Country Name Grade Level Minimum Midpoint Maximum Currency Currency Name 07/01/2021 Africa Region ANGOLA GI USD United States Dollars 07/01/2021 Africa Region ANGOLA GH 211,310 301,870 392,430 USD United States Dollars 07/01/2021 Africa Region ANGOLA GG 150,790 215,420 280,050 USD United States Dollars 07/01/2021 Africa Region ANGOLA GF 109,110 155,870 202,630 USD United States Dollars 07/01/2021 Africa Region ANGOLA GE 74,360 106,230 138,100 USD United States Dollars 07/01/2021 Africa Region ANGOLA GD 52,020 74,310 96,600 USD United States Dollars 07/01/2021 Africa Region ANGOLA GC 40,580 57,970 75,360 USD United States Dollars 07/01/2021 Africa Region ANGOLA GB 31,630 45,190 58,750 USD United States Dollars 07/01/2021 Africa Region ANGOLA GA 23,280 33,260 43,240 USD United States Dollars 07/01/2021 Africa Region ANGOLA G1 19,120 27,310 35,500 USD United States Dollars 3 FY22 Net Salary Scales, Benin Effective Date Region Country Name Grade Level Minimum Midpoint Maximum Currency Currency Name 07/01/2021 Africa Region BENIN GI XOF C.F.A. -

AGI Markets Monitor: African Equity Markets Gain, Sovereign Bonds Face Pressure, and Most Currencies Decline Against the Dollar July 2018 Update

AGI Markets Monitor: African equity markets gain, sovereign bonds face pressure, and most currencies decline against the dollar July 2018 update Amadou Sy & Amy Copley The Africa Growth Initiative (AGI) Markets Monitor aims to provide up-to-date financial market and foreign exchange analysis for Africa watchers with a wide range of economic, business, and financial interests in the continent. Following the previous updates in 2016 and 2017, the July 2018 update continues tracking the diverse performances of African financial and foreign exchange markets through the first half of 2018 (2018 H1) and provides a summary of developments throughout 2017. We offer our main findings on key events influencing the region’s economies: rising energy prices, gains in certain African equity markets, a reversal in sovereign bond sentiment, and declines in dollar terms for most of the region’s currencies. Key trends in 2018 H1 Commodity markets: Energy and agricultural prices rose in 2018 H1, but metal prices fell slightly. In particular, throughout 2017 and 2018 H1, energy prices continued to recover from the 2014 slump, which adversely affected macroeconomic conditions in oil-exporting countries such as Angola, Cameroon, Chad, Gabon, Nigeria, and the Republic of the Congo. Strengthening oil prices—which have risen from a monthly averages of $54 per barrel in January 2017 to $73 per barrel in May 2018—have eased some of the fiscal pressure on these countries. Equity markets: In 2018 H1, the MSCI Emerging Frontier Markets in Africa (excluding South Africa) Index overperformed the emerging markets benchmark while several African equity markets—including Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria—continued to rally after noteworthy performances in 2017. -

Daily Foreign Exchange Rates Monday, 01 April 2019

Daily Foreign Exchange Rates Monday, 01 April 2019 CURR T/T BUYING CHEQUES BANK NOTES SELLING MID-RATE CURRENCY NAME USD 14.2000 14.1760 14.1657 14.5500 14.3750 U.S. DOLLAR GBP 18.4714 18.4359 18.4239 19.0154 18.7434 BRITISH POUND CAD 0.0949 0.0953 0.0954 0.0909 0.0929 CANADIAN DOLLAR SCR 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.9089 0.4544 SEYCHELLES RUPEE CHF 0.0712 0.0715 0.0716 0.0675 0.0693 SWISS FRANC SEK 0.6588 0.6601 0.6607 0.6313 0.6450 SWEDISH KRONA NOK 0.6148 0.6161 0.6167 0.5817 0.5982 NORWEGIAN KRONE DKK 0.4732 0.4742 0.4746 0.4521 0.4626 DANISH KRONE JPY 7.9190 7.9326 7.9385 7.5416 7.7303 JAPANESE YEN NZD 0.1055 0.1059 0.1063 0.0981 0.1018 NEW ZEALAND DOLLAR AUD 0.1005 0.1010 0.1017 0.0948 0.0976 AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR HKD 0.5591 0.5601 0.5607 0.5327 0.5459 HONG KONG DOLLAR MWK 52.0810 52.2148 52.8237 49.4391 50.7600 MALAWI KWACHA SGD 0.0973 0.0976 0.0978 0.0912 0.0942 SINGAPORE DOLLAR BWP 0.7713 0.7726 0.7766 0.6832 0.7272 BOTSWANA PULA SZL 1.0000 1.0000 1.0000 1.0000 1.0000 SWAZI LILANGENI MUR 2.5025 2.5176 2.5285 2.3204 2.4114 MAURITIUS RUPEE KES 7.3803 7.5280 7.5856 6.5430 6.9616 KENYAN SHILLING LSL 1.0000 1.0000 1.0000 1.0000 1.0000 LESOTHO LOTI INR 4.9278 4.9451 4.9525 4.7003 4.8140 INDIAN RUPEE NAD 1.0000 1.0000 1.0000 1.0000 1.0000 NAMIBIAN DOLLAR EUR 15.8955 15.8615 15.8472 16.3993 16.1474 EURO ILS 0.2596 0.2601 0.2687 0.2448 0.2522 ISRAELI SHEKEL THB 2.3852 2.3988 2.4116 2.0254 2.2053 THAI BAHT CNY 0.4790 0.0000 0.4979 0.4536 0.4663 CHINESE YUAN AED 0.2619 0.0000 0.2724 0.2492 0.2555 UAE DIRHAM GHS 0.0000 0.0000 0.0000 0.3735 0.1867