Dance: the Universal Language of Storytellers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg

Cal Performances Presents Program Friday, May 1, 2009, 8pm Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg Saturday, May 2, 2009, 8pm Artistic Director Sunday, May 3, 2009, 3pm Boris Eifman, Zellerbach Hall Soloists Maria Abashova, Elena Kuzmina, Natalia Povorozniuk, Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg Anastassia Sitnikova, Nina Zmievets Boris Eifman, Artistic Director Yuri Ananyan, Dmitry Fisher, Oleg Gabyshev, Andrey Kasyanenko, Ivan Kozlov, Oleg Markov, Yuri Smekalov Company Marina Burtseva, Valentina Vasilieva, Polina Gorbunova, Svetlana Golovkina, Alina Gornaya, Diana Danchenko, Ekaterina Zhigalova, Evgenia Zodbaeva, Sofia Elistratova, Elena Kotik, Yulia Kobzar, Alexandra Kuzmich, Marianna Krivenko, Marianna Marina, Alina Petrova, Natalia Pozdniakova, Victoria Silantyeva, Natalia Smirnova, Agata Smorodina, Alina Solonskaya, Oksana Tverdokhlebova, Lina Choe Sergey Barabanov, Sergey Biserov, Maxim Gerasimov, Pavel Gorbachev, Anatoly Grudzinsky, Vasil Dautov, Kirill Efremov, Sergey Zimin, Mikhail Ivankov, Alexander Ivanov, Andrey Ivanov, Aleksandr Ivlev, Stanislav Kultin, Anton Labunskas, Dmitry Lunev, Alexander Melkaev, Batyr Niyazov, Ilya Osipov, Artur Petrov, Igor Polyakov, Roman Solovyov Ardani Artists Management, Inc., is the exclusive North American management for Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg. Valentin Baranovsky Valentin Onegin (West Coast Premiere) Choreography by Boris Eifman Ballet in Two Acts Inspired by Alexander Pushkin’s novel, Eugene Onegin Music by Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky and Alexander Sitkovetsky Cal Performances’ 2008–2009 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo Bank. 6 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 7 Program Cast Friday, May 1, 2009, 8pm Onegin Saturday, May 2, 2009, 8pm Sunday, May 3, 2009, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Onegin music Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893) Variations on a Rococo Theme in A major, Op. 33 (1876) Suite No. 3 in G major, Op. -

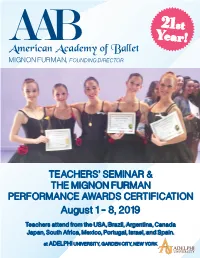

The Mignon Furman Performance Awards 1000S of Dancers!

21st AAB Year! American Academy of Ballet MIGNON FURMAN, FOUNDING DIRECTOR TEACHERS’ SEMINAR & THE MIGNON FUR MAN PERFORMANCE AWARDS CERTIFICATION August 1 – 8, 2019 Teachers attend from the USA, Brazil, Argentina, Canada Japan, South Africa, Mexico, Portugal, Israel, and Spain. at ADELPHI UNIVERSITY, GARDEN CITY, NEW YORK REASONS TO ATTEND THE SEMINAR Mignon Furman 10 AND THE PERFORMANCE AWARDS Founder of the AAB, Teacher, Choreographer, Educationist. CERTIFICATION EVERYTHING MOVES FORWARD. “ THEREFORE, I RECOMMEND: ith her talents, courage, and determination KEEP IN TOUCH WITH YOUR ART. to give definition to her vision for ballet PERFORMANCE AWARDS — AGRIPPINA VAGANOVA, ” Weducation, Mignon Furman founded the American and “Steps” programs. Most wonderful programs for “BASIC PRINCIPLES OF CLASSICAL BALLET” (1934) Academy of Ballet: It soon became the premier teachers and their dancers. (View the brochures on Summer School in the United States. our website.) he composed the Performance Awards S which are taught all over the USA, and are an CERTIFICATION : international phenomenon, praised by teachers Become a certified Performance Awards teacher. in the USA and in many other countries. The Hang your diploma in your studio. success of the Performance Awards is due to Mignon’s choreography: She was a superb choreographer. Her many compositions are FOUR DANCES : free of cliché. They have logic, harmony, style, To teach in your school. (See page 5.) and intrinsic beauty. OBSERVE : Our distinguished argot Fonteyn, a friend of Mignon, gave faculty teaching our Summer School dancers. her invaluable advice, during several You have the option of taking the classes. Mdiscussions about the technical, and artistic aspects of classical ballet. -

Gainesville Ballet Contact

Gainesville Ballet Contact: Elysabeth Muscat 7528 Old Linton Hall Road [email protected] Gainesville, VA 20155 703-753-5005 www.gainesvilleballetcompany.org FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 1, 2015 ABT BALLET STARS BOYLSTON AND WHITESIDE IN GAINESVILLE BALLET NUTCRACKER GAINESVILLE, Va. – Gainesville Ballet is excited to announce two performances of The Nutcracker on Friday, November 27, 2015 at 2 PM and 7 PM. The full-length ballet features ballet superstars, international guest dancers, the professional dancers of Gainesville Ballet Company, and the students of Gainesville Ballet School. What better way to continue the celebration of the Thanksgiving holiday weekend, than to see a beautiful, professional performance of The Nutcracker at the elegant opera house of the 1,123-seat Merchant Hall at the Hylton Performing Arts Center! Audiences who reside in Northern Virginia and beyond will have the rare opportunity to see two of American Ballet Theatre’s most exciting Principal Dancers, Isabella Boylston and James Whiteside. James Whiteside and Isabella Boylston in Giselle. Isabella Boylston was promoted to Principal Dancer at American Ballet Photo by MIRA. Theatre in 2014. She originally joined ABT as part of the Studio Company in 2005, joined the main company as an apprentice in 2006, and became a member of the corps de ballet in 2007. She was promoted to Soloist in 2011, before recently becoming Principal. Boylston began dancing at the age of three at The Boulder Ballet. At age 12, she joined the Academy of Colorado Ballet in Denver, Colorado, where she commuted two hours on a public bus to study there each day. -

Ballet West Student In-Theater Presentations

Ballet West for Children Presents Ballet and The Sleeping Beauty Dancers: Soloist Katie Critchlow, First Soloist Sayaka Ohtaki, Principal Artist Emily Adams, First Soloist Katlyn Addison, Demi-Soloist Lindsay Bond Photo by Beau Pearson Music: Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky Adapted from Original Choreography: Marius Petipa Photo: Quinn Farley Costumes: David Heuvel Dear Dance enthusiast, Ballet West is pleased that you are viewing a Ballet West for Children Presentation as a virtual learning experience. Enclosed you will find the following information concerning this performance: 1. Letter from Artistic Director, Adam Sklute. 2. Letter to the parent/guardian of the students who will be viewing. 3. Specific Information on this Performance, including information on the ballet, music, choreography, follow-up projects and other pertinent material has also been compiled for the teacher's information. 4. We report to the Utah State Board of Education each year on our educational programs, and need your help. Usually, we gather information from teachers as to how the student reacted and what they may have learned from their experience. We’d love to hear from you by filling out our short Survey Monkey listed on our virtual learning page. We don’t have a way to track who and how many people are taking advantage of this opportunity and this will help us to know how we’re doing. You can always email me directly. Thank you very much for your interest in the educational programs of Ballet West. Please call if I may provide any additional information or assistance to you and your school. I can be reached at 801-869-6911 or by email at [email protected]. -

August 14, 2007

September 23, 2020 Dear Dancers and Parents, We now have approval to film the Nutcracker on the Russell stage! The filming dates are Friday, Saturday, Sunday, November 20-22. Each class will be filmed by appointment, for an hour. Every dancer will be in a mask. We will color coordinate these. We will give you that schedule asap, but please go ahead and save those dates on your calendar. No overlapping of classes on the filming dates. We have to film before Thanksgiving because our college students will not be back on campus after Thanksgiving. On the day of filming, each class may have ONE adult only, in mask, present in the audience to watch that class or dance film, in the back of Russell, or in the balcony, socially distanced. DVDs will be sold of the Nutcracker. The cast list will be posted on Monday at Miller and Chappell studio! It will also be posted on our dance web site. Remember we are cutting some dances this year, and shortening the bigger scenes of Party Scene, Kingdom of Sweets, Mice and Soldier, and the Finale due to limiting dancers on stage to 21. The rehearsal schedule will be posted on Monday as well! This is your information letter about ordering Nutcracker costumes. We are using the SAME costumes as last year. Remember to order a size up so that they may be worn in the spring concert in May!! (Creative Movement will have a different costume in the spring concert). Please order UP if in any doubt!! There are size charts by the pictures as well. -

Dorothy O'shea Overbey

Dorothy O’Shea Overbey 917-434-6958 [email protected] 1507 East 14th Street,, Austin, TX, 78702 rednightfallproductions.com dorothyoshea.com Current/Ongoing Projects, 2020 CRONE - THE VIRTUAL REALITY FILM, 2017-2020 Producer, Writer, Director, Choreographer. Crone is a hybrid: part dance film, part fashion film, part music film that uses orchestral music, visual art and dance to tell a story of transformation. Fueled by a desire to help dance, music, and all performing arts reach new audiences, Crone will be shot with 360 degree capture technology to create a Virtual Reality film. A cross-media project, Crone will also be made as a traditional film for release to festival and theaters, and a live-performance version of the work was presented by University of Texas Department of Theatre and Dance in November 2017. Crone received grant support from the City of Austin Cultural Funding Division. CRONE TEASER/TRAILER Producer, Production Designer, Writer, Director, Choreographer. In collaboration with composer Sam Lipman and Emmy-winning Producer Whitney Rowlett. Teaser/trailer to raise funds for the upcoming film. Choreography/Production/Performance History VIRTUAL COLOR FIELD - FILM COLLABORATION WITH AUSTIN CAMERATA, RELEASED APRIL 30, 2020 Film Producer. A collaboration between Red Nightfall Productions and Austin Camerata featuring five string musicians and five dancers filming their collaborations while quarantined during the time of COVID-19. Dancers hailing from a diverse range of dance traditions (Heels Technique, Tap Dance, Contemporary Ballet, Modern Dance, Dance Theatre) interpret the music of Johann Sebastian Bach while exploring themes of connection in a time of social distancing. VENTANA BALLET SPRING 2020 SEASON - LEAP - FEBRUARY 2020, FIRST STREET STUDIO THEATER, AUSTIN TEXAS Artistic Advisor and Choreographer, setting new works and performing with Ventana Ballet. -

Concert Hour Ballet

19 20 SEASON Concert Hour Ballet CANADA’S ROYAL WINNIPEG BALLET SCHOOL 380 GRAHAM AVENUE WINNIPEG, MB, CANADA | R3C 4K2 T 204.957.3467 E [email protected] W RWB.ORG/SCHOOL @RWBSCHOOL #RWBSAUDITIONS RWB.ORG/CONCERTHOUR PHOTO ROYAL WINNIPEG BALLET SCHOOL PROFESSIONAL DIVISION STUDENTS, BY KRISTEN SAWATZKY CONCERT HOUR STUDY GUIDE | 1 Be Transported For 60 minutes in your school Michelle Blais : PHOTO Concert Hour Ballet, a one-hour narrated dance performance, Concert Hour Ballet is an opportunity provides the perfect introduction to a variety of dance forms for everyone in your school community and an engaging springboard for further study and exploration. to sit back, relax, and be amazed. Performances may include jazz, modern, and other dance forms in addition to classical ballet. Concert Hour Ballet offers Bringing the pure athleticism, grace, and artistry of ballet a rare opportunity to see dancers up close. right into your school, the senior dancers in the RWB School Ballet Academic Program will entertain students and staff Let this be the experience that calls your students to go alike. Concert Hour Ballet is an opportunity for the RWB out and see more dance performances or even try dance School’s dancers to share their passion, hard work and for themselves! dedication as young artists. DID YOU KNOW … ? Whether touring the world’s stages, visiting schools, offering challenging dance classes for all experience levels, or performing The word ‘ballet’ refers to a specific dance technique that has Ballet in the Park each summer, the RWB consistently delivers evolved over the last 350 years. -

Shanna Zordell (Executive Assistant), 563-663-2120 - [email protected] Download This Media Kit in Printable PDF Format

! FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 21, 2018 Contact: Shanna Zordell (Executive Assistant), 563-663-2120 - [email protected] Download this media kit in printable PDF format. Among this year’s Momentum works: Matthew Lovegood’s French Songs (left); Erika Overturff’s Connemara; and Overturff’s Rhapsody in Blue. More full-resolution photos... NEW BRAND, NEW DANCERS, NEW WORKS IN AMERICAN MIDWEST BALLET'S MOMENTUM OMAHA — The freshly rebranded American Midwest Ballet — formerly known as Ballet Nebraska — will open its ninth season in October with a fresh crop of works, artistic director Erika Overturff said. “Our mixed repertory program, Momentum, has been a must-see since our earliest seasons, because it showcases the exciting range of dance as an expressive art,” Overturff said. “For its first American Midwest Ballet edition, we're mixing some past favorites with works that will be new experiences for our audiences.” Headlining the selection is Overturff's Rhapsody in Blue, to the iconic music of George Gershwin. “When I choreographed it, I listened to the music many times until I knew all of the rhythms and notes by heart,” Overturff said. “The music is so expressive; within one piece it conveys so many different moods. It is flirty, jazzy, big and bold, whiny and sad, sweeping and romantic, daring and quick – lots of personality! “I see the dancers as a personification of the musical notes themselves, as if they floated out of the instruments and onto the stage for us to see.” ! Among the program’s other highlights are three guest works: Frank Chaves’ sultry, flirtatious At Last, is a duet set to lyrics sung by the incomparable Etta James. -

National Ballet of Canada Agreement (NBCA)

NBCA begins July 1, 2019 | terminates June 30, 2022 2019 - 2022 NATIONAL BALLET OF CANADA AGREEMENT OF CANADA BALLET NATIONAL Table of Contents PREAMBLE 1 1:00 ARTISTS COVERED 1 1:01 Recognition of Equity ------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 1:02 Independent Contractor --------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 2:00 MEMBERSHIP IN EQUITY 1 2:01 Artists in Good Standing--------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 2:02 Membership------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 3:00 APPLICATION OF THE AGREEMENT 1 3:01 Application of the Agreement -------------------------------------------------------------- 1 3:02 Parties Bound by Agreement -------------------------------------------------------------- 2 4:00 INITIATION FEES AND DUES 2 4:01 Deduction and Remittance ----------------------------------------------------------------- 2 5:00 ADMITTANCE OF EQUITY REPRESENTATIVE ON ENGAGER’S PREMISES 2 5:01 Access to Workplace and Notification --------------------------------------------------- 2 6:00 THE COMMUNICATIONS COMMITTEE 2 6:01 Establishment and Purpose ---------------------------------------------------------------- 2 6:02 Procedure --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 (A) Composition ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 3 (B) Absences ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 (C) -

Curriculum Overview Level 3 Ballet Curriculum Overview | Level 3

CURRICULUM OVERVIEW LEVEL 3 BALLET CURRICULUM OVERVIEW | LEVEL 3 CURRICULUM Level 3 Ballet Together’s Level 3 Curriculum serves as a guide for dance instructors around the world to teach their students the building blocks of ballet. The curriculum for this level is selected to gradually introduce new movements and vocabulary so students can feel confident progressing through each class and quarter term. Dance instructors are advised to use the curriculum overview provided as a guide to build their own weekly or monthly syllabus, depending on the frequency of the classes offered. The Ballet Together Teacher Training & Certificate will work more in depth with instructors one-on-one to give them the tools to build their own syllabus documents to serve their own dance schools and students. For more information or to get involved, contact the BT Global Team at: http://www.ballettogether.com/. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION…………………………………….Page 3 CURRICULUM……….……………………………….Page 4 RECOMMENDED STRETCHES…………………….Page 6 RECOMMENDED VARIATIONS…………………….Page 6 BALLET CLASS MUSIC TRACKS…………..……….Page 7 Page 2 Copyright © 2020 Ballet Together - All Rights Reserved. BALLET CURRICULUM OVERVIEW | LEVEL 3 INTRODUCTION Level 3 The Ballet Together Global Team has put together a few guiding points to help dance instructors feel prepared to use this curriculum document successfully. They are as follows: ● AGE + EXPERIENCE RECOMMENDATIONS ○ AGES: 12+ years old or Intermediate Adult Ballet student. ■ 1-3 years of prior ballet experience required. ■ Appropriate for both men and women. ○ CLASS FREQUENCY: Classes should be held 3-4 times per week for a 1-hour and 30-minute time period. ● 12-WEEK QUARTER TERMS ○ Each level is divided into three 12-week (or 3 months) quarter terms. -

Summer Ballet Intensive Is Led by an Choreographer – Having Created International Faculty

Faculty – Instructors Guest Instructors HERE PLACE PLACE STAMP STAMP ANNA-MARIE HOLMES ELDIYAR DANIYAROV Ballet Former Artistic Director of Boston Ballet and Program Director, Jacob’s Pillow, Kyrgyzstan native Eldiyar has a degree in Teaching and New York. Choreography from the National Academy of Art. Before joining Atlantic Ballet Theatre in 2012 he was a principal dancer with several companies including the prestigious Eifman Ballet of St. Petersburg. Artistic director, choreographer, master teacher, and celebrated ballerina, Anna-Marie Holmes is an internationally acclaimed dance luminary. Former Artistic Director of Boston Ballet and Head of the Ballet Program for Jacob’s Pillow, New York, she was the first North YURIKO DIYANOVA Ballet American invited to perform with the Kirov Ballet in Russia, and also appeared with leading classical companies Yuriko left a career as a classical in Canada, England, Germany, Netherlands, and others. soloist in Japan to join Atlantic Her stagings of the Russian classic ballets are in the Ballet Theatre in 2003. A repertoires of leading ballet companies worldwide, and prizewinner at several ballet she is a master coach of principals and soloists in competitions, she has an companies such as American Ballet Theatre and English extensive classical repertoire National Ballet. Holmes is a recipient of the prestigious SUMMER which includes principal and Dance Magazine Award and an Emmy Award for her soloist roles. staging of Le Corsaire for American Ballet Theatre's PBS Great Performances. BALLET INTENSIVE ALLEN KAEJA WITH Co-Artistic Director, Kaeja INTERNATIONAL Contact Us: d’Dance, Kaeja Elevations, Partnering and Contemporary Atlantic Ballet Theatre Dance Teacher. -

August 14, 2007

August 18, 2021 Dear Dancers and Parents, This is your information letter about ordering Nutcracker costumes. Costume Orders are due FRIDAY, September 17th! Check size charts! Do not rely on Amelia or the instructor to tell you what size to order! You are responsible for the size you order for your dancer. There are three ways to order your costume. 1. Online: You may order costumes online at the following website: https://www.gcsu.edu/ce/community-dance-continuing-and-professional-education 2. By Phone: Please call 478-445-5277, Monday-Friday, 8 a.m.-5 p.m. Payment by credit card can be accepted. Please confirm the correct costume and size from your e-mailed receipt. 3. In Person: Please visit 100 Chappell Hall at Georgia College, Continuing Education registration office to pay by cash, check, or card during regular business hours. Remember to order a size up so that they may be worn in the spring concert in May!! (Creative Movement will have a different costume in the spring concert). Please order UP if in any doubt!! Pictures of the costumes are on the bulletin boards by the dance studios. There are size charts by the pictures as well. The cast list will be posted at both Milledgeville dance studios very soon. Nutcracker Costumes 2021 Creative Movement - Baby Mice Cost: $72.00. Sizes: XSC- XXLC. Pink tights and pink ballet shoes. Pink tights, pink ballet shoes for girls. Black ballet shoes for boys. We will draw on whiskers. Adult/Teen Beginning Ballet - Adult Mice We have these. Sizes: Adult small, med., lg.