The Francophone Belgian Case Study', Transnational Cinemas, 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Catalogue

LIBRARY "Something like Diaz’s equivalent "Emotionally and visually powerful" of Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville" THE HALT ANG HUPA 2019 | PHILIPPINES | SCI-FI | 278 MIN. DIRECTOR LAV DIAZ CAST PIOLO PASCUAL JOEL LAMANGAN SHAINA MAGDAYAO Manilla, 2034. As a result of massive volcanic eruptions in the Celebes Sea in 2031, Southeast Asia has literally been in the dark for the last three years, zero sunlight. Madmen control countries, communities, enclaves and new bubble cities. Cataclysmic epidemics ravage the continent. Millions have died and millions more have left. "A dreamy, dreary love story packaged "A professional, polished as a murder mystery" but overly cautious directorial debut" SUMMER OF CHANGSHA LIU YU TIAN 2019 | CHINA | CRIME | 120 MIN. DIRECTOR ZU FENG China, nowadays, in the city of Changsha. A Bin is a police detective. During the investigation of a bizarre murder case, he meets Li Xue, a surgeon. As they get to know each other, A Bin happens to be more and more attracted to this mysterious woman, while both are struggling with their own love stories and sins. Could a love affair help them find redemption? ROMULUS & ROMULUS: THE FIRST KING IL PRIMO RE 2019 | ITALY, BELGIUM | EPIC ACTION | 116 MIN. DIRECTOR MATTEO ROVERE CAST ALESSANDRO BORGHI ALESSIO LAPICE FABRIZIO RONGIONE Romulus and Remus are 18-year-old shepherds twin brothers living in peace near the Tiber river. Convinced that he is bigger than gods’ will, Remus believes he is meant to become king of the city he and his brother will found. But their tragic destiny is already written… This incredible journey will lead these two brothers to creating one of the greatest empires the world has ever seen, Rome. -

Catalogue-2018 Web W Covers.Pdf

A LOOK TO THE FUTURE 22 years in Hollywood… The COLCOA French Film this year. The French NeWave 2.0 lineup on Saturday is Festival has become a reference for many and a composed of first films written and directed by women. landmark with a non-stop growing popularity year after The Focus on a Filmmaker day will be offered to writer, year. This longevity has several reasons: the continued director, actor Mélanie Laurent and one of our panels will support of its creator, the Franco-American Cultural address the role of women in the French film industry. Fund (a unique partnership between DGA, MPA, SACEM and WGA West); the faithfulness of our audience and The future is also about new talent highlighted at sponsors; the interest of professionals (American and the festival. A large number of filmmakers invited to French filmmakers, distributors, producers, agents, COLCOA this year are newcomers. The popular compe- journalists); our unique location – the Directors Guild of tition dedicated to short films is back with a record 23 America in Hollywood – and, of course, the involvement films selected, and first films represent a significant part of a dedicated team. of the cinema selection. As in 2017, you will also be able to discover the work of new talent through our Television, Now, because of the continuing digital (r)evolution in Digital Series and Virtual Reality selections. the film and television series industry, the life of a film or series depends on people who spread the word and The future is, ultimately, about a new generation of foreign create a buzz. -

Here Was Obviously No Way to Imagine the Event Taking Place Anywhere Else

New theatre, new dates, new profile, new partners: WELCOME TO THE 23rd AND REVAMPED VERSION OF COLCOA! COLCOA’s first edition took place in April 1997, eight Finally, the high profile and exclusive 23rd program, years after the DGA theaters were inaugurated. For 22 including North American and U.S Premieres of films years we have had the privilege to premiere French from the recent Cannes and Venice Film Festivals, is films in the most prestigious theater complex in proof that COLCOA has become a major event for Hollywood. professionals in France and in Hollywood. When the Directors Guild of America (co-creator This year, our schedule has been improved in order to of COLCOA with the MPA, La Sacem and the WGA see more films during the day and have more choices West) decided to upgrade both sound and projection between different films offered in our three theatres. As systems in their main theater last year, the FACF board an example, evening screenings in the Renoir theater made the logical decision to postpone the event from will start earlier and give you the opportunity to attend April to September. The DGA building has become part screenings in other theatres after 10:00 p.m. of the festival’s DNA and there was obviously no way to imagine the event taking place anywhere else. All our popular series are back (Film Noir Series, French NeWave 2.0, After 10, World Cinema, documentaries Today, your patience is fully rewarded. First, you will and classics, Focus on a filmmaker and on a composer, rediscover your favorite festival in a very unique and TV series) as well as our educational program, exclusive way: You will be the very first audience to supported by ELMA and offered to 3,000 high school enjoy the most optimal theatrical viewing experience in students. -

Adoration Fr-Nl-En

PRESENTE / PRESENTEERT ADORATION un film de / een film van Fabrice du Welz avec / met Thomas Gioria, Fantine Harduin, Benoît Poelvoorde, Laurent Lucas, Peter Van den Begin, Charlotte Vandermeersch, Anaël Snoek, Gwendolyn Gourvenec FESTIVAL DE LOCARNO 2019 – PIAZZA GRANDE FIFF 2019 – COMPETITION : Prix d’interprétation pour Fantine Harduin & Thomas Gioria SITGES FESTIVAL 2019 - OFICIAL FANTÀSTIC COMPETICIÓN : Special Jury Prize - Best Photography - Manu Dacosse - Special Mention of the Jury for Thomas Gioria & Fantine Harduin Méliès d'Argent (award given to the best European fantastic genre feature film) FESTIVAL DU NOUVEAU CINEMA MONTREAL 2019 BFI LONDON 2019 © Kris Dewitte Belgique, France / België, Frankrijk – 2019 – DCP – Couleur/Kleur – 2.35 – 5.1 VO FR avec ST NL / FR OV met NL OT - 98’ Distribution / Distributie : IMAGINE SORTIE NATIONALE RELEASE 15/01/2020 T : 02 331 64 31 / M Tinne Bral : 0499 25 25 43 photos / foto's : http://press.imaginefilm.be press : THE PR FACTORY Marie-France Dupagne : [email protected] & Barbara Van Lombeek : [email protected] SYNOPSIS FR ADORATION, c’est l’histoire de Paul, un jeune garçon solitaire de 14 ans. Sa mère est femme de ménage dans une clinique psychiatrique. Son père les a quittés il y a déjà très longtemps. Une nouvelle patiente arrive à la clinique. Elle s’appelle Gloria, une adolescente trouble et solaire. Paul va en tomber amoureux fou et s’enfuir avec elle, loin du monde des adultes… NL ADORATION is het verhaal van Paul, een 14-jarige dromer. Zijn moeder is werkvrouw in een psychiatrisch ziekenhuis. Zijn vader is lang geleden uit hun leven verdwenen. -

Le PRIX De La JEUNESSE Au Festival De Cannes - Repères Historiques

Le PRIX de la JEUNESSE Au festival de Cannes - Repères historiques Document mis à jour le 9 janvier 2021 Nota Comme leur nom l’indique, ces fiches « Repères historiques » sont l’indication chronologique des principaux faits marquants liés au sujet traité. Elles ne visent pas à être des analyses approfondies. Leur objectif est simplement de donner au lecteur des indications de bases, en lui permettant, s’il le désire, d’aller « plus loin ». Dans le cas précis, il s’agit d’un témoignage d’acteur, « source d’information primaire », susceptible d’être utilisée par des historiens et chercheurs, avec d’autres sources, le cas échéant. En 2013, le prix de la Jeunesse n’a pas été reconduit par le ministère. Plan I - Historique et modalités - De la dimension locale à une dimension européenne • De 1982 à 1988 • De 1989 à 2002 II - Une reconnaissance croissante au sein d’une manifestation internationale • De 2003 à 2009 • De 2010 à 2013, un changement de nature III - L’organisation IV - L’encadrement des jeunes • Comment rendre les jeunes acteurs du projet ? • Comment relier un travail éducatif à une approche du monde professionnel ? • Comment intégrer une dimension européenne ? V - Partenariat et éducation populaire • Les projections au quartier Ranguin • Les sélections parallèles, une éducation au regard VI - Communication VII - Évaluation et conclusion VIII - Palmarès %%%% Prix de la Jeunesse - Festival de Cannes 1 CHMJS La volonté de proposer un événement pour les jeunes pendant le festival de Cannes, re- connu comme le plus important festival de cinéma au monde, revient à Edwige Avice, ministre de la Jeunesse et des Sports de 1981 à 1984, l’idée d’un prix décerné par un jury de jeunes lui ayant été suggérée par Frédéric Mitterrand. -

Cinéma JACQUES BREL

cinéma JACQUES BREL PROGRAMME02/16 1 place de l’Hôtel de Ville 95140 - Garges-lès-Gonesse [email protected] rel 01 34 53 32 26 Cinéma Jacques B T ARDS OP TON CINÉMA CHOCOLA ARRÊTE Comédie Un film de Roschdy Zem Western Un film de Diane Kurys France, 2014, 1 h 50 LES 8Un SAfilm Lde Quentin Tarantino France, 2015, 1 h 30 Avec Omar Sy, Laurent Borel, États-Unis, 2 h 50, 2015 VO & VF Avec Sylvie Testud, Josiane Balasko, Avec Bruce Dern, Zoe Bell, Du cirque au théâtre, de l’anonymat à Sybille démarre l’écriture de son la gloire, l’incroyable destin du clown Quelques années après la Guerre premier film. Actrice reconnue, elle va Chocolat, premier artiste noir de la de Sécession, le chasseur de primes passer pour la première fois de l’autre scène française. John Ruth, conduit sa prisonnière Daisy côté de la caméra. Domergue se faire pendre. ANISH GIRL LES SAISONS Un film de Jacques Perrin THE D Drame Comédie & Jacques Cluzaud Un film de Tom Hooper ENCOREUn HEUREUX film de Benoît Graffin Documentaire États-Unis, 2015, 2 h, VO France, 2015, 1 h 30 France, 2015, 1 h 35 Avec Eddie Redmayne, Amber Heard Avec Sandrine Kiberlain, Edouard Baer Jacques Perrin et Jacques Cluzaud L’histoire d’amour de Gerda et Lili reviennent pour ce nouvel opus sur Wegener, artiste danoise connue Marie est un peu fatiguée de des terres plus familières. comme la première personne à avoir l’insouciance de son mari Sam, cadre subi une chirurgie de réattribution sup au chômage depuis 2 ans. -

François Cluzet in 11.6

Pan-Européenne Presents In Association with Wild Bunch François Cluzet in 11.6 A film by Philippe Godeau Starring Bouli Lanners and Corinne Masiero Written by Agnès de Sacy and Philippe Godeau Loosely based on Alice Géraud "Toni 11.6 Histoire du convoyeur" 1h42 - Dolby SRD - Scope - Visa n°133.508 High definition pictures and press kit can be downloaded from www.wildbunch.biz SYNOPSIS Toni Musulin. Security guard. Porsche owner. Loner. Enigma. An ordinary man seeking revenge for humiliation at the hands of his bosses. A man with a slow-burning hatred of the system. And the man behind "the heist of the century". Q&A with Philippe Godeau After ONE FOR THE ROAD, how did you decide to make a film about this one-of-a-kind €11.6 million heist? From the very beginning, what mattered to me wasn't so much the heist as the story of that man who'd been an armoured car guard for ten years with no police record, and who one day decided to take action. How come this punctual, hard- working, seemingly perfect, lonely employee, who kept his distance from unions, ended up pulling off the heist of the century and went to the other side? With the screenwriter Agnès de Sacy, this was our driving force. What was it that drove him to take action? We did a lot of research, we visited the premises, and we met some of his co-workers, some of his acquaintances, his lawyers… What about the real Toni Musulin? Did you actually meet him? I didn't. -

Joachim Lafosse Bérénice Bejo Cédric Kahn

LES FILMS DU WORSO AND VERSUS PRODUCTION PRESENT BÉRÉNICE BEJO CÉDRIC KAHN A FILM BY JOACHIM LAFOSSE Les films du Worso and Versus production present A FILM BY JOACHIM LAFOSSE WITH BÉRÉNICE BEJO AND CÉDRIC KAHN 100MIN - BELGIUM/FRANCE - 2016 - SCOPE - 5.1 INTERNATIONAL PRESS ALIBI COMMUNICATIONS INTERNATIONAL SALES Brigitta PORTIER In Cannes: Unifrance – Village International 5, rue Darcet French mobile: +33 6 28 96 81 65 (from May10th) 75017 Paris International mobile: +32 4 77 98 25 84 Phone: +33 1 44 69 59 59 [email protected] Press materials available for download on www.le-pacte.com SYNOPSIS After 15 years of living together, Marie and Boris decide to get a divorce. Marie had bought the house in which they live with their two daughters, but it was Boris who had completely renovated it. Since he cannot afford to find another place to live, they must continue to share it. When all is said and done, neither of the two is willing to give up. We sense that the two girls are quite disrupted by the situation. At the same time, they give INTERVIEW WITH the impression that they are quite comprehensive regarding the very strict rules imposed by Marie on Boris, just like they’re comprehensive regarding the father’s transgressions: “It’s not JOACHIM LAFOSSE his day”, Jade will tell Margaux, so as to explain the embarrassment which follows Boris’s presence in the house on a Wednesday afternoon. Marie seems to sets all the rules. She’s in charge. Boris does not have a say, but in a way this situation allows What triggered the idea of the film? How did you write it? him to set his own rule. -

Long Métrage Feature Film

LONG MÉTRAGE FEATURE FILM Hiver | 2020 | Winter CENTRE DU CINÉMA ET DE L’AUDIOVISUEL WALLONIE BRUXELLES IMAGES MINISTÈRE DE LA FÉDÉRATION WALLONIE-BRUXELLES SERVICE GÉNÉRAL DE L’AUDIOVISUEL ET DES MÉDIAS CENTRE DU CINÉMA ET DE L’AUDIOVISUEL PROMOTION EN BELGIQUE Boulevard Léopold II 44 - B-1080 Bruxelles T +32 (0)2 413 22 44 [email protected] www.centreducinema.be WALLONIE BRUXELLES IMAGES PROMOTION INTERNATIONALE Place Flagey 18 - B-1050 Bruxelles T +32 (0)2 223 23 04 [email protected] www.wbimages.be LONG MÉTRAGE ÉDITEUR RESPONSABLE Frédéric Delcor - Secrétaire Général Boulevard Léopold II 44 - B-1080 Bruxelles PUBLICATION Février / February 2020 COUVERTURE / COVER Jumbo de Zoé Wittock Production : Kwassa Films © Caroline Fauvet LONG MÉTRAGE FEATURE FILM Hiver | 2020 | Winter CENTRE DU CINÉMA ET DE L’AUDIOVISUEL WALLONIE BRUXELLES IMAGES SOMMAIRE CONTENT ADORABLES................................ SOLANGE CICUREL .......................... 4 ADORATION ................................ FABRICE DU WELZ ........................... 5 ANIMALS .................................. NABIL BEN YADIR ............................ 6 APRÈS LA FIN .............................. FRANÇOIS HIEN ............................. 7 BULA ...................................... BORIS BAUM ............................... 8 DES HOMMES .............................. LUCAS BELVAUX ............................. 9 FILLES DE JOIE ............................. FRÉDÉRIC FONTEYNE & ANNE PAULICEVICH ...... 10 FILS DE PLOUC ............................. LENNY GUIT & HARPO GUIT -

Activity Results for 2015

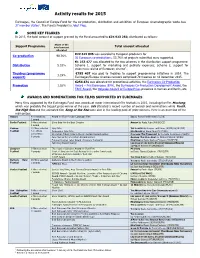

Activity results for 2015 Eurimages, the Council of Europe Fund for the co-production, distribution and exhibition of European cinematographic works has 37 member states1. The Fund’s President is Jobst Plog. SOME KEY FIGURES In 2015, the total amount of support granted by the Fund amounted to €24 923 250, distributed as follows: Share of the Support Programme total amount Total amount allocated allocated €22 619 895 was awarded to European producers for Co-production 90.76% 92 European co-productions. 55.76% of projects submitted were supported. €1 253 477 was allocated to the two schemes in the distribution support programme: Distribution 5.03% Scheme 1, support for marketing and publicity expenses; Scheme 2, support for awareness raising of European cinema2. Theatres (programme €795 407 was paid to theatres to support programming initiatives in 2014. The 3.19% support) Eurimages/Europa Cinemas network comprised 70 theatres on 31 December 2015. €254 471 was allocated for promotional activities, the Eurimages Co-Production Promotion 1.02% Award – Prix Eurimages (EFA), the Eurimages Co-Production Development Award, the FACE Award, the Odyssée-Council of Europe Prize, presence in Cannes and Berlin, etc. AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS FOR FILMS SUPPORTED BY EURIMAGES Many films supported by the Eurimages Fund won awards at major international film festivals in 2015, including the film Mustang, which was probably the biggest prize-winner of the year. Ida attracted a record number of awards and nominations while Youth, the High Sun and the animated film Song of the Sea were also in the leading pack of prize-winners. -

2011-Catalogue.Pdf

>> Le Festival existegrâceausoutiende/ Le Festival PARTENAIRES The Festival receives supportfrom receives The Festival SPONSORS 1 192 > INDEX 175 > ACTIONS VERS LES PUBLICS 179 > RENCONTRES 167 > AUTRES PROGRAMMATIONS 105 > HOMMAGES ET RÉTROSPECTIVES 19 > SELECTION OFFICIELLE 01 > LE FESTIVAL PARTENAIRES SPONSORS LE FESTIVAL >> Le Festival remercie / The Festival would like to thank Académie de Nantes • ACOR • Andégave communication • Arte • Artothèque • Atmosphères Production • Bibliothèque Universitaire d’Angers • Bureau d’Accueil des Tournages des Pays de la Loire • Capricci • Films Centre national de danse contemporaine • Centre Hospitalier Universitaire • Cinéma Parlant • CCO - Abbaye de Fontevraud • Commission Supérieure Technique • Ecole Supérieure des Beaux-Arts • Ecole Supérieure des Pays de la Loire • Ecran Total • Eden Solutions • Elacom • Esra Bretagne • Fé2A • Filminger • France 2 • France Culture • Keolis Angers Cotra • Forum des Images • Ford Rent Angers • Héliotrope • Imprimerie Setig Palussière • Inspection Académique de Maine-et-Loire • Institut municipal d’Angers • JC Decaux • La fémis • Les Films du camion • Les Vitrines d’Angers • Musées d’Angers • Nouveau Théâtre d’Angers • OPCAL • Pôle emploi Spectacle • SCEREN – CDDP de Maine-et-Loire • Tacc Kinoton • Université d’Angers • Université Catholique de l’Ouest Ambassade de France à Berlin • Ambassade de France en République tchèque • Ambassade de France en Russie • Ambassade d’Espagne à Paris • British Council • Centre culturel Français Alexandre Dumas de Tbilissi • -

Long Métrage Feature Film

LONG MÉTRAGE FEATURE FILM 02/2018 CENTRE DU CINÉMA ET DE L’AUDIOVISUEL WALLONIE-BRUXELLES IMAGES MINISTÈRE DE LA FÉDÉRATION WALLONIE-BRUXELLES SERVICE GÉNÉRAL DE L’AUDIOVISUEL ET DES MÉDIAS CENTRE DU CINÉMA ET DE L’AUDIOVISUEL PROMOTION EN BELGIQUE Boulevard Léopold II 44 - B-1080 Bruxelles T +32 (0)2 413 22 44 Thierry Vandersanden - Directeur [email protected] www.centreducinema.be WALLONIE BRUXELLES IMAGES PROMOTION INTERNATIONALE Place Flagey 18 - B-1050 Bruxelles T +32 (0)2 223 23 04 [email protected] - www.wbimages.be Éric Franssen - Directeur LONG MÉTRAGE [email protected] ÉDITEUR RESPONSABLE Frédéric Delcor - Secrétaire Général Boulevard Léopold II 44 - B-1080 Bruxelles COUVERTURE / COVER DUELLES de Olivier Masset-Depasse Production : Versus production © G.Chekaiban LONG MÉTRAGE FEATURE FILM 02/2018 CENTRE DU CINÉMA ET DE L’AUDIOVISUEL WALLONIE-BRUXELLES IMAGES SOMMAIRE CONTENTS BITTER FLOWERS . OLIVIER MEYS . 6 CARNIVORES . JÉRÉMIE & YANNICK RÉNIER . 7 CAVALE . VIRGINIE GOURMEL . 8 CONTINUER . JOACHIM LAFOSSE . 9 DEMAIN DÈS L’AUBE . DELPHINE NOELS . 10 DOUBLEPLUSUNGOOD . MARCO LAGUNA . 11 DRÔLE DE PÈRE . AMÉLIE VAN ELMBT . 12 DUELLES . OLIVIER MASSET-DEPASSE . 13 ESCAPADA . SARAH HIRTT . 14 FOR A HAPPY LIFE . DIMITRI LINDER & SALIMA GLAMINE . 15 LAISSEZ BRONZER LES CADAVRES . BRUNO FORZANI & HÉLÈNE CATTET . 16 MÉPRISES . BERNARD DECLERCQ . 17 NOS BATAILLES . GUILLAUME SENEZ . 18 PART SAUVAGE (LA) . GUÉRIN VAN DE VORST . 19 PIVOINE (LA) . JOAQUIN BRETON . 20 POLINA . OLIAS BARCO . 21 ROI DE LA VALLÉE (LE) . OLIVIER RINGER & YVES RINGER . 22 SEULE À MON MARIAGE . MARTA BERGMAN . 23 SUICIDE D'EMMA PEETERS (LE) . NICOLE PALO . 24 THE MERCY OF THE JUNGLE . JOËL KAREKEZI .