Use of Lucilia Species for Forensic Investigations in Southern Europe S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Folk Taxonomy, Nomenclature, Medicinal and Other Uses, Folklore, and Nature Conservation Viktor Ulicsni1* , Ingvar Svanberg2 and Zsolt Molnár3

Ulicsni et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2016) 12:47 DOI 10.1186/s13002-016-0118-7 RESEARCH Open Access Folk knowledge of invertebrates in Central Europe - folk taxonomy, nomenclature, medicinal and other uses, folklore, and nature conservation Viktor Ulicsni1* , Ingvar Svanberg2 and Zsolt Molnár3 Abstract Background: There is scarce information about European folk knowledge of wild invertebrate fauna. We have documented such folk knowledge in three regions, in Romania, Slovakia and Croatia. We provide a list of folk taxa, and discuss folk biological classification and nomenclature, salient features, uses, related proverbs and sayings, and conservation. Methods: We collected data among Hungarian-speaking people practising small-scale, traditional agriculture. We studied “all” invertebrate species (species groups) potentially occurring in the vicinity of the settlements. We used photos, held semi-structured interviews, and conducted picture sorting. Results: We documented 208 invertebrate folk taxa. Many species were known which have, to our knowledge, no economic significance. 36 % of the species were known to at least half of the informants. Knowledge reliability was high, although informants were sometimes prone to exaggeration. 93 % of folk taxa had their own individual names, and 90 % of the taxa were embedded in the folk taxonomy. Twenty four species were of direct use to humans (4 medicinal, 5 consumed, 11 as bait, 2 as playthings). Completely new was the discovery that the honey stomachs of black-coloured carpenter bees (Xylocopa violacea, X. valga)were consumed. 30 taxa were associated with a proverb or used for weather forecasting, or predicting harvests. Conscious ideas about conserving invertebrates only occurred with a few taxa, but informants would generally refrain from harming firebugs (Pyrrhocoris apterus), field crickets (Gryllus campestris) and most butterflies. -

Status and Trends of the Pollinators' Population in the Country

1 Status and trends of the pollinators’ population in the country Agriculture is one of the core sectors of the economy Order Families Species of the Rep.of Moldova contributing to the gross 12%, whereas to the food Diptera Sarcophagidae Sarcophaga carnaria domestic product by about Califoridae Lucilia caesar industry the contribution amounts to 40% of the total Syrphidae Syrphus ribesii industry. The volume and the quality of the agricultural Eristalis tenax products depend directly on the pollinators’ status. Spherophoria scripta Tachinidae Tachina fera Hymenoptera Apidae Apis mellifera Spp. The most widely spread species of pollinators in the Andrenidae Andrena bucephala and Rep.of Moldova are from Hymenoptera Ord.– more over 48 SPP. 100 SPP., that the ants, bees, bumble bees, wasps Scoliidae Scolia hirta Formicidae Formica rufa belong to, are phytophage which feed on flower nectar Lasius niger and fruit juice and are social species. Coleoptera are Helicidae 45 Spp. widely spread in different terrestrial and aquatic Vespidae Katamenes arbustorum habitats. Diptera are cosmopolitan species of different Coleoptera Coccinelidae Coccinella septempunctata forms: pollinating, parasitic, predatory, saprophagous, Adalia bipunctata hemophage that easily adapt to different life Adalia quadrimaculata conditions. Harmonia axyridis Cantharidae Rhagonycha fulva Scarabeidae Cetonia aurata 2 Status and trends of the pollinators’ population in the country In the Republic of Moldova, there is a large number of invertebrate species: Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN) and Vulnerable (VU), which have been included into the 3rd Edition of the Red Book of the Republic of Moldova and are important for plants’ pollination (Annex 2, fig.2). The largest ones come from the Apidae fam. -

A Brief Survey of the History of Forensic Entomology 15

A brief survey of the history of forensic entomology 15 Acta Biologica Benrodis 14 (2008): 15-38 A brief survey of the history of forensic entomology Ein kurzer Streifzug durch die Geschichte der forensischen Entomologie MARK BENECKE International Forensic Research & Consulting, Postfach 250411, D-50520 Köln, Germany; [email protected] Summary: The fact that insects and other arthropods contribute to the decomposition of corpses and even may help to solve killings is known for years. In China (13th century) a killer was convicted with the help of flies. Artistic contributions, e.g. from the 15th and 16th century, show corpses with “worms”, i.e. maggots. At the end of the 18th and in the beginning of the 19th century forensic doctors pointed out the significance of maggots for decomposition of corpses and soon the hour of death was determined using pupae of flies (Diptera) and larval moths (Lepidoptera) as indicators. In the eighties of the 19th century, when REINHARD and HOFMANN documented adult flies (Phoridae) on corpses during mass exhumation, case reports began to be replaced by systematic studies and entomology became an essential part of forensic medicine and criminology. At nearly the same time the French army veterinarian MÉGNIN recognized that the colonisation of corpses, namely outside the grave, takes place in predictable waves; his book “La faune des cadavres” published in 1894 is a mile stone of the forensic entomology. Canadian (JOHNSTON & VILLENEUVE) and American (MOTTER) scientists have been influenced by MÉGNIN. Since 1895 the former studied forensically important insects on non buried corpses and in 1896 and 1897 MOTTER published observations on the fauna of exhumed corpses, the state of corpses as well as the composition of earth and the time of death of corpses in the grave. -

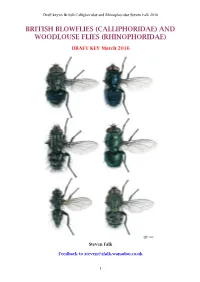

Test Key to British Blowflies (Calliphoridae) And

Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016 BRITISH BLOWFLIES (CALLIPHORIDAE) AND WOODLOUSE FLIES (RHINOPHORIDAE) DRAFT KEY March 2016 Steven Falk Feedback to [email protected] 1 Draft key to British Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae Steven Falk 2016 PREFACE This informal publication attempts to update the resources currently available for identifying the families Calliphoridae and Rhinophoridae. Prior to this, British dipterists have struggled because unless you have a copy of the Fauna Ent. Scand. volume for blowflies (Rognes, 1991), you will have been largely reliant on Van Emden's 1954 RES Handbook, which does not include all the British species (notably the common Pollenia pediculata), has very outdated nomenclature, and very outdated classification - with several calliphorids and tachinids placed within the Rhinophoridae and Eurychaeta palpalis placed in the Sarcophagidae. As well as updating keys, I have also taken the opportunity to produce new species accounts which summarise what I know of each species and act as an invitation and challenge to others to update, correct or clarify what I have written. As a result of my recent experience of producing an attractive and fairly user-friendly new guide to British bees, I have tried to replicate that approach here, incorporating lots of photos and clear, conveniently positioned diagrams. Presentation of identification literature can have a big impact on the popularity of an insect group and the accuracy of the records that result. Calliphorids and rhinophorids are fascinating flies, sometimes of considerable economic and medicinal value and deserve to be well recorded. What is more, many gaps still remain in our knowledge. -

Key for Identification of European and Mediterranean Blowflies (Diptera, Calliphoridae) of Forensic Importance Adult Flies

Key for identification of European and Mediterranean blowflies (Diptera, Calliphoridae) of forensic importance Adult flies Krzysztof Szpila Nicolaus Copernicus University Institute of Ecology and Environmental Protection Department of Animal Ecology Key for identification of E&M blowflies, adults The list of European and Mediterranean blowflies of forensic importance Calliphora loewi Enderlein, 1903 Calliphora subalpina (Ringdahl, 1931) Calliphora vicina Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830 Calliphora vomitoria (Linnaeus, 1758) Cynomya mortuorum (Linnaeus, 1761) Chrysomya albiceps (Wiedemann, 1819) Chrysomya marginalis (Wiedemann, 1830) Chrysomya megacephala (Fabricius, 1794) Phormia regina (Meigen, 1826) Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830) Lucilia ampullacea Villeneuve, 1922 Lucilia caesar (Linnaeus, 1758) Lucilia illustris (Meigen, 1826) Lucilia sericata (Meigen, 1826) Lucilia silvarum (Meigen, 1826) 2 Key for identification of E&M blowflies, adults Key 1. – stem-vein (Fig. 4) bare above . 2 – stem-vein haired above (Fig. 4) . 3 (Chrysomyinae) 2. – thorax non-metallic, dark (Figs 90-94); lower calypter with hairs above (Figs 7, 15) . 7 (Calliphorinae) – thorax bright green metallic (Figs 100-104); lower calypter bare above (Figs 8, 13, 14) . .11 (Luciliinae) 3. – genal dilation (Fig. 2) whitish or yellowish (Figs 10-11). 4 (Chrysomya spp.) – genal dilation (Fig. 2) dark (Fig. 12) . 6 4. – anterior wing margin darkened (Fig. 9), male genitalia on figs 52-55 . Chrysomya marginalis – anterior wing margin transparent (Fig. 1) . 5 5. – anterior thoracic spiracle yellow (Fig. 10), male genitalia on figs 48-51 . Chrysomya albiceps – anterior thoracic spiracle brown (Fig. 11), male genitalia on figs 56-59 . Chrysomya megacephala 6. – upper and lower calypters bright (Fig. 13), basicosta yellow (Fig. 21) . Phormia regina – upper and lower calypters dark brown (Fig. -

Biodiversity Changes in Vegetation and Insects Following the Creation of a Wildflower Strip

Hochschule Rhein-Waal Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences Faculty of Communication and Environment Biodiversity changes in vegetation and insects following the creation of a wildflower strip A Case Study Bachelor Thesis by Johanna Marquardt Hochschule Rhein-Waal Rhine-Waal University of Applied Sciences Faculty of Communication and Environment Biodiversity changes in vegetation and insects following the creation of a wildflower strip A Case Study A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Bachelor of Science In Environment and Energy by Johanna Marquardt Matriculation Number: 23048 Supervised by Prof. Dr. Daniela Lud Prof. Dr. Petra Blitgen-Heinecke Submission Date: 22.02.2021 Abstract With the Global Climate Change, the loss of biodiversity is one of the most current and biggest crises of today and the future. The loss i.e., the decrease of biodiversity, does not only have negative effects on vegetation and animals, but also on humans. If nature is doing well, people are doing well. In order to counteract the loss, this bachelor thesis attempts to increase plant and insect biodiversity at a specific location with insect-friendly seed mixtures and by measuring the change using comparison areas. Accordingly, the two research questions were addressed: (1) "How does plant-biodiversity change in the backyard and front yard on the seed mixture plot compared to plant-biodiversity in the backyard and front yard next to the seed mixture plot?" and (2) "How does insect-biodiversity change in the backyard and front yard on the seed mixture plot compared to insect-biodiversity in the backyard and front yard next to the seed mixture plot?" To answer these research questions and to obtain more suitable data, a wildflower strip was established in the backyard and one in the front yard, each with an adjacent reference field, to ensure equal environmental conditions and to detect changes in flora and fauna. -

An Assessment of the Sanitary Importance of Sixteen Blowfly Species

Acta rerum naturalium 3: 29–36, 2007 ISSN 1803-1587 An assessment of the sanitary importance of sixteen blowfl y species (Diptera: Calliphoridae) Hodnocení zdravotního významu šestnácti druhů bzučivkovitých (Diptera: Calliphoridae) OLDŘICH ARNOŠT FISCHER Boří 3, CZ – 644 00 Brno-Útěchov; e-mail: o.a.fi [email protected] Abstract: A total 3857 imagos of blowfl ies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) originating from 30 localities in South Moravia (Czech Republic) were cap- tured from 1999 to 2006 to be classifi ed by the awarding of points in terms of their potential for the transmission of causative agents of infectious diseases of man and animals (degree of danger). Sixteen species of Calliphoridae obtained points for visiting of municipal waste, carcasses or meat baits, faeces of animals or human stool and rooms or stables. Calliphora loewi Enderlein, 1903, Cynomya mortuorum (Linnaeus, 1761) and Lucilia pilosiventris Kramer, 1910 were assessed as non-dangerous, because they did not win any points. C. uralensis Villeneuve, 1922, Chrysomya albiceps Wiedemann, 1819, L. ampullacea Villeneuve, 1922, L. regalis (Meigen, 1826) and L. richardsi Collin, 1926 were assessed as potentially dangerous (1–5 points). Calliphora vomitoria (Linnaeus, 1758), Phormia regina (Meigen, 1826) and Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830) were assessed as dangerous (6–9 points). C. vicina (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830), L. caesar (Linnaeus, 1758), L. illustris (Meigen, 1826), L. sericata (Meigen, 1826) and L. silvarum (Meigen, 1826) were assessed as very dangerous (10–20 points). The most dangerous blowfl y, C. vicina, received 20 points, because it occurred at 21 (70 %) of the 30 localities under study. Key words: insect vectors, synanthropy of fl ies, Moravia, Czech Republic. -

Etude Des Interactions Entre L'entomofaune Et Un Cadavre

COMMUNAUTE FRANCAISE DE BELGIQUE ACADEMIE UNIVERSITAIRE WALLONIE-EUROPE UNIVERSITE DE LIEGE – GEMBLOUX AGRO-BIO TECH Etude des interactions entre l’entomofaune et un cadavre: approches biologique, comportementale et chémo-écologique du coléoptère nécrophage, Thanatophilus sinuatus Fabricius (Col., Silphidae) Jessica DEKEIRSSCHIETER Essai présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de docteur en sciences agronomiques et ingénierie biologique Promoteurs: Prof. Eric Haubruge Prof. Georges Lognay 2012 -2- -3- Copyright. Aux termes de la loi belge du 30 juin 1994, sur le droit d'auteur et les droits voisins, seul l'auteur a le droit de reproduire partiellement ou complètement cet ouvrage de quelque façon et forme que ce soit ou d'en autoriser la reproduction partielle ou complète de quelque manière et sous quelque forme que ce soit. Toute photocopie ou reproduction sous autre forme est donc faite en violation de la dite loi et de des modifications ultérieures -4- Dekeirsschieter Jessica (2012). Etude des interactions entre l’entomofaune et un cadavre: approches biologique, comportementale et chémo-écologique du coléoptère nécrophage, Thanatophilus sinuatus Fabricius (Col., Silphidae) (thèse de doctorat). Gembloux, Belgique, Université de Liege, Gembloux Agro- Bio Tech, 277 p., 28 tabl., 47 fig. Résumé – La décomposition d’un corps entraîne des changements physiques et biochimiques importants, le cadavre va émettre des odeurs attractives pour certaines espèces et d’autres moins attractives. Au sein des écosystèmes terrestres tempérés, les insectes sont généralement les principaux organismes qui colonisent un corps selon une séquence plus ou moins prédictive. Ces insectes nécrophages et/ou nécrophiles, principalement des Diptères et des Coléoptères, utilisent le micro- habitat créé par le cadavre comme un substrat nourricier, un site de reproduction, un refuge ou encore comme un territoire de chasse. -

Promoting Pollinators Along the Area 9 Road Network

Inspiring change for Important Invertebrate Areas in the UK 11th September 2014 Susan Thompson - Grants & Trusts Officer Saving the small things that run the planet Steven Falk March 2017 1 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction and background .................................................................................................... 4 Site selection ............................................................................................................................. 4 Methods .................................................................................................................................. 10 Results ..................................................................................................................................... 16 Total number of pollinators recorded ............................................................................ 16 Most frequent pollinators .............................................................................................. 17 Most abundant pollinators ............................................................................................. 18 Total flowers recorded ................................................................................................... 18 Most frequent flowers ................................................................................................... -

Forensically Important Calliphoridae (Diptera) Associated with Animal and Human Decomposition in the Czech Republic: Preliminary Results

ISSN 1211-3026 Čas. Slez. Muz. Opava (A), 62: 255-266, 2013 DOI: 10.2478/cszma-2013-0024 Forensically important Calliphoridae (Diptera) associated with animal and human decomposition in the Czech Republic: preliminary results Hana Šuláková & Miroslav Barták Forensically important Calliphoridae (Diptera) associated with animal and human decomposition in the Czech Republic: preliminary results. – Čas. Slez. Muz. Opava (A), 62: 255-266, 2013. Abstract: Two studies to establish standards of sampling of entomological evidence for crime scene technicians and forensic experts in the Czech Republic were pursued in years 2011 to 2013. During experiments, pigs (Sus scrofa f. domestica Linnaeus, 1758) were used as models for human bodies and important data about succession of decomposition of large carcasses were also obtained. Altogether 21 species of Calliphoridae were collected, of which ten are classified as forensically important: Lucilia caesar (Linnaeus, 1758), Calliphora vicina Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830, Phormia regina (Meigen, 1826), Protophormia terraenovae (Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830), Lucilia illustris (Meigen, 1826), Lucilia ampullacea Villeneuve, 1922, Calliphora vomitoria (Linnaeus, 1758), Lucilia sericata (Meigen, 1826), Lucilia silvarum (Meigen, 1826), and Cynomya mortuorum (Linnaeus, 1761). The next eleven species belonged to genera Bellardia Robineau-Desvoidy, 1836, Melinda Robineau- Desvoidy, 1830, Onesia Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830, and Pollenia Robineau-Desvoidy, 1830; the blow flies associated with earthworms and snails, and their role in decomposition is discussed. Finally, our results stated that a pyramidal trap along with pitfall traps and rearing of larvae from the carcass are suitable tool for successional studies of forensically important invertebrates. Key words: Diptera, Calliphoridae, decomposition, forensic entomology, pyramidal trap Introduction Forensic entomology is a particular field of criminalistics which is based on knowledge of invertebrate fauna succession on cadavers. -

The State of Germany's Biodiversity for Food And

COUNTRY REPORTS THE STATE OF GERMANY’S BIODIVERSITY FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE This country report has been prepared by the national authorities as a contribution to the FAO publication, The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture. The report is being made available by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as requested by the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the content of this document is entirely the responsibility of the authors, and does not necessarily represent the views of FAO, or its Members. The designations employed and the presentation of material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Country Report Germany The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture 28.10.2015 Guidelines for the preparation of the Country Reports for The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture TABLE OF CONTENT List of abbreviations and acronyms AbL German Small Farmers' Association ADT German Animal Breeders Federation AECM Agri-environment-climate measures AEM Agri-environment -

An Introduction to the Immature Stages of British Flies

Royal Entomological Society HANDBOOKS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF BRITISH INSECTS To purchase current handbooks and to download out-of-print parts visit: http://www.royensoc.co.uk/publications/index.htm This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License. Copyright © Royal Entomological Society 2013 Handbooks for the Identification of British Insects Vol. 10, Part 14 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE IMMATURE STAGES OF BRITISH FLIES DIPTERA LARVAE, WITH NOTES ON EGGS, PUP ARIA AND PUPAE K. G. V. Smith ROYAL ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON Handbooks for the Vol. 10, Part 14 Identification of British Insects Editors: W. R. Dolling & R. R. Askew AN INTRODUCTION TO THE IMMATURE STAGES OF BRITISH FLIES DIPTERA LARVAE, WITH NOTES ON EGGS, PUPARIA AND PUPAE By K. G. V. SMITH Department of Entomology British Museum (Natural History) London SW7 5BD 1989 ROYAL ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON The aim of the Handbooks is to provide illustrated identification keys to the insects of Britain, together with concise morphological, biological and distributional information. Each handbook should serve both as an introduction to a particular group of insects and as an identification manual. Details of handbooks currently available can be obtained from Publications Sales, British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD. Cover illustration: egg of Muscidae; larva (lateral) of Lonchaea (Lonchaeidae); floating puparium of Elgiva rufa (Panzer) (Sciomyzidae). To Vera, my wife, with thanks for sharing my interest in insects World List abbreviation: Handbk /dent. Br./nsects. © Royal Entomological Society of London, 1989 First published 1989 by the British Museum (Natural History), Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD.