Environmental Impact Assessment And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mayor Muesee Kazapua Also Said Yesterday That Madikizela-Mandela Deserves a Street to Be Named After Her

11111 Media Monitoring on Urban Development in Namibia Media Monitoring on Urban Development in Namibia is a service provided by Development Workshop Namibia (DWN), a Namibian NGO with a focus on sustainable urban development and poverty reduction. DWN is part of a world-wide network of Development Workshop (DW) organisations with centres in Canada, Angola and France, and offices in Vietnam and Burkino Faso. It was founded in the 1970s by three architect students in the UK and has been funded by non- governmental organisations, private citizens, and national and international development organisations. In Namibia, DWN’s activities focus on urban related research, effective urban planning for the urban poor, solutions to informal settlements, water & sanitation, and projects specifically targeting disadvantaged segments of the urban youth. Through 40 years of engagement on urban issues mainly in Africa and Asia, the DW network of organisations has acquired significant institutional knowledge and capacity and is well integrated in regional and international networks. The Namibian media provide an important source of information on urban development processes in the country, highlighting current events, opportunities and challenges. The media further provide insight into the different views and perceptions of a variety of actors, be it from government, non- government, private sector, and individuals that reside in Namibia’s towns and settlements. It is therefore hoped that DWN’s Media Monitoring service will provide insights into those different views, with potential use for a variety of institutions and decision-makers that work in the urban environment in Namibia. The Media Monitoring service is currently provided on a monthly basis and monitors the following newspapers: The Namibian, Republikein, Namibian Sun, New Era, Windhoek Observer, Confidente, and Informante. -

Sustainable Urban Transport Master Plan City of Windhoek

Sustainable Urban Transport Master Plan City of Windhoek Final - Main Report 1 Master Plan of City of Windhoek including Rehoboth, Okahandja and Hosea Kutako International Airport The responsibility of the project and its implementation lies with the Ministry of Works and Transport and the City of Windhoek Project Team: 1. Ministry of Works and Transport Cedric Limbo Consultancy services provided by Angeline Simana- Paulo Damien Mabengo Chris Fikunawa 2. City of Windhoek Ludwig Narib George Mujiwa Mayumbelo Clarence Rupingena Browny Mutrifa Horst Lisse Adam Eiseb 3. Polytechnic of Namibia 4. GIZ in consortium with Prof. Dr. Heinrich Semar Frederik Strompen Gregor Schmorl Immanuel Shipanga 5. Consulting Team Dipl.-Volksw. Angelika Zwicky Dr. Kenneth Odero Dr. Niklas Sieber James Scheepers Jaco de Vries Adri van de Wetering Dr. Carsten Schürmann, Prof. Dr. Werner Rothengatter Roloef Wittink Dipl.-Ing. Olaf Scholtz-Knobloch Dr. Carsten Simonis Editors: Fatima Heidersbach, Frederik Strompen Contact: Cedric Limbo Ministry of Works and Transport Head Office Building 6719 Bell St Snyman Circle Windhoek Clarence Rupingena City of Windhoek Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH P.O Box 8016 Windhoek,Namibia, www.sutp.org Cover photo: F Strompen, Young Designers Advertising Layout: Frederik Strompen Windhoek, 15/05/2013 2 Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 15 1.1. Purpose ........................................................................................................................................ -

Environmental Management Plan: - July 2020

FEBRUARY 2020 REPORT NUMBER: APP001063 ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGE MENT PLAN: FOR DULUX NAMIBIA’S WATER-BASED PAINT MANUFACTURING FACILITY ON ERF 2, NUBU INDUSTRIAL PARK, WINDHOEK PROPONENT: CONSULTANT: JF PAINTS (PTY) LTD. URBAN DYNAMICS AFRICA (PTY) LTD. P. O. BOX 11568 P. O. BOX 20837 WINDHOEK WINDHOEK NAMIBIA NAMIBIA SUBMISSION: REFERENCE: 1190 MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT FORESTRY ENQUIRIES: HEIDRI BINDEMANN-NEL AND TOURISM PRIVATE BAG 13306 Tel: +264-61-240300 WINDHOEK Fax: +264-61-240309 NAMIBIA DULUX NAMIBIA -ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN: - JULY 2020 PREPARED BY URBAN DYNAMICS AFRICA PTY (LTD) i DULUX NAMIBIA -ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN: - JULY 2020 GENERAL LOCATION DESCRIPTION OF THE DEVELOPMENT AREA: DESCRIPTOR: LOCATION SPECIFICS: ACTIVITIES: Land Use and Development Activities REGISTRATION DIVISION: K REGION: Khomas Region LOCAL AUTHORITY: Municipality of Windhoek (City of Windhoek) Fall Within: The City of Windhoek's Townlands NEAREST TOWNS / CITY: Windhoek LAND USE: Industrial HOMESTEADS/STRUCTURES: None HISTORICAL RESOURCE LISTINGS: None CEMETERY: None ENVIRONMENTAL SIGNIFICANT AREA: None ERF 2, NUBU INDUSTRIAL PARK PROJECT SITE SIZE 4 149 Sqm LATITUDE: -22. 46066 S, LONGITUDE: 17.077314 E PREPARED BY URBAN DYNAMICS AFRICA PTY (LTD) ii DULUX NAMIBIA -ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN: - JULY 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 2 RESPONSIBILITIES ................................................................................................................... -

Integrated Annual Report

INTEGRATED ANNUAL REPORT ’20 ORYX is a property loan stock company listed on the Namibian Stock Exchange (NSX) in the Financial Our 2020 performance at a glance IFC Real Estate sector. We are directly invested in property Oryx’s evolution 1 mainly in Namibia and have an How we compiled this report 2 investment in Croatia. This is our Integrated Annual Report What is important to know about Oryx 3 for the financial year ended What impacts our business 10 30 June 2020. Where we are going 16 Our leadership’s review of 2020 18 CONTENTS How we support our communities 33 How we practise good governance 36 How we reward performance 57 Appendices to the Integrated Annual Report 64 Annual Financial Statements 70 FEEDBACK Unitholder information and notice of AGM 150 Oryx is committed to improving its reporting, aligned Glossary 163 with best practice. Please provide any feedback and questions to [email protected]. Corporate information as at the date of this report 164 OUR 2020 PERFORMANCE AT A GLANCE Total distribution Property portfolio Market capitalisation 69.75 (cents per unit (cpu)) N$1.528 N$2.914 value (2019: N$1.704 billion) CPU (2019: 150.00) Bn Bn (2019: N$2.914 billion) Net asset value Net rental Gearing ratio N$1.912 (NAV) income growth 2.0% 39.1% (2019: 34.9%) Bn (2019: N$2.043 billion) (2019: 12%) Overall weighted Interest cover ratio Vacancy rate average cost of 2.3 (excluding interest (excluding 5.83% funding on linked debentures) 5.40% residentials) (2019: 9.2%1) times (2019: 2.96 times) (2019: 3.20%) 1 Excludes Euro loan. -

EPL Contacts__03 March 2021 093529

License Code Responsible License Status Date Applied Date Granted Date Expires Commodities Map References Area Parties Contact Details Office Type Communication Party Postal Address Physical Address Telephone Email Address 2101 EPL Pending 31 August 27 April 1995 26 April 2014 PS Namibia,Karas,Karasbu 2869.8107 Northbank Diamonds Northbank Diamonds 061-240956/7 Renewal 1994 rg; V Ha (Pty) Limited (100%) (Pty) Limited 2229 EPL Pending 15 January 24 March 1999 21 February BRM, PM Namibia,Karas,Luderitz 8785.7000 Skorpion Mining Company Skorpion Mining P/Bag 2003, Rosh Pinah, 26 Km North of 061- 241740 Renewal 1999 2021 ; N; 2716 Ha (Pty) Ltd. (100%) Company (Pty) Ltd. //Karas, 9000, Namibia Roshpinah C13 Rd, Rosh Pinah, //Karas, 9000, Namibia 2410 EPL Pending 15 June 2012 15 September 05 May 2021 BRM, IM, PM, P Namibia,B, 35622.7147 B2Gold Namibia (Pty) Ltd B2Gold Namibia (Pty) P.O Box 80363, 20 Nachtigal Street, 26461295870 Lhoffmann@b2g Renewal 1997 Otjozondjupa,Grootfo Ha Ltd Olympia, Windhoek, Ausspannplatz, 0 old.com ntein; 1917, 2016, Khomas, 9000, Namibia Windhoek, Khomas, 2017 9000, Namibia 2491 EPL Active 25 January 07 April 1997 18 September PS 26071.3576 Togethe Quando Mining 2013 2020 Ha (Pty) Ltd (100%) 2616 EPL Active 30 August 27 September 30 November BRM, PM Namibia,Karas,Luderitz 15060.0113 PE Minerals (Namibia) PE Minerals (Namibia) PO Box 4750, 3rd Floor, Mandume Park 26461260153 coen@wayconam 2013 2000 2021 ; N; 2716 Ha (Pty) Ltd (100%) (Pty) Ltd Windhoek, Khomas, Building, c/o Teinert & .com 9000, Namibia Dr Kulz Streets, Windhoek, Khomas, 9000, Namibia 2902 EPL Pending 02 February 18 April 2001 19 February BRM, PM Namibia,Erongo,Swak 1866.5747 Namib Lead and Zinc Namib Lead and Zinc 26464426250 Renewal 2001 2021 opmund; G; 2214A Ha Mining (Pty) Ltd (100%) Mining (Pty) Ltd 3138 EPL Pending 24 November 20 April 2004 19 April 2021 BRM, IM, Nf, PM Namibia,Erongo,Swak 24196.7483 Swakop Uranium (Pty) Swakop Uranium (Pty) P. -

Housing Index in Due Course to Provide a Comparable Sectional Property Index

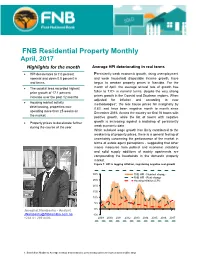

FNB Residential Property Monthly April, 2017 Highlights for the month Average HPI deteriorating in real terms HPI decelerates to 7.0 percent Persistently weak economic growth, rising unemployment nominal and down 0.8 percent in and weak household disposable income growth, have real terms. begun to weaken property prices in Namibia. For the The coastal area recorded highest month of April, the average annual rate of growth has price growth of 17.1 percent fallen to 7.0% in nominal terms, despite the very strong increase over the past 12 months prices growth in the Coastal and Southern regions. When adjusted for inflation and according to new Housing market activity methodologies¹, the real house prices fell marginally by deteriorating, properties now 0.8% and have been negative month to month since spending more than 25 weeks on December 2016. Across the country we find 16 towns with the market. positive growth, while the list of towns with negative Property prices to decelerate further growth is increasing against a backdrop of persistently during the course of the year. weak economic data. While subdued wage growth has likely contributed to the weakening of property prices, there is a general feeling of uncertainty concerning the performance of the market in terms of estate agent perceptions - suggesting that other macro measures from political and economic instability and solid supply additions of mainly apartments are compounding the headwinds in the domestic property market. Figure 1: HPI is lagging inflation, registering negative real growth 30% FNB HPI - Nominal change FNB HPI - Real change 25% Housing Inflation (CPI) 20% 15% 10% 5% Josephat Nambashu - Analyst 0% [email protected] -5% +264 61 299 8496 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 1. -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$9.00 WINDHOEK - 12 March 2021 No. 7480 Advertisements PROCEDURE FOR ADVERTISING IN 7. No liability is accepted for any delay in the publi- THE GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE cation of advertisements/notices, or for the publication of REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA such on any date other than that stipulated by the advertiser. Similarly no liability is accepted in respect of any editing, 1. The Government Gazette (Estates) containing adver- revision, omission, typographical errors or errors resulting tisements, is published on every Friday. If a Friday falls on from faint or indistinct copy. a Public Holiday, this Government Gazette is published on the preceding Thursday. 8. The advertiser will be held liable for all compensa- tion and costs arising from any action which may be insti- 2. Advertisements for publication in the Government tuted against the Government of Namibia as a result of the Gazette (Estates) must be addressed to the Government Ga- publication of a notice with or without any omission, errors, zette office, Private Bag 13302, Windhoek, or be delivered lack of clarity or in any form whatsoever. at Justitia Building, Independence Avenue, Second Floor, Room 219, Windhoek, not later than 12h00 on the ninth 9. The subscription for the Government Gazette is working day before the date of publication of this Govern- N$4,190-00 including VAT per annum, obtainable from ment Gazette in which the advertisement is to be inserted. Solitaire Press (Pty) Ltd., corner of Bonsmara and Brahman Streets, Northern Industrial Area, P.O. Box 1155, Wind- 3. -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$6.00 WINDHOEK - 7 May 2021 No. 7530 Advertisements PROCEDURE FOR ADVERTISING IN 7. No liability is accepted for any delay in the publi- THE GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE cation of advertisements/notices, or for the publication of REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA such on any date other than that stipulated by the advertiser. Similarly no liability is accepted in respect of any editing, 1. The Government Gazette (Estates) containing adver- revision, omission, typographical errors or errors resulting tisements, is published on every Friday. If a Friday falls on from faint or indistinct copy. a Public Holiday, this Government Gazette is published on the preceding Thursday. 8. The advertiser will be held liable for all compensa- tion and costs arising from any action which may be insti- 2. Advertisements for publication in the Government tuted against the Government of Namibia as a result of the Gazette (Estates) must be addressed to the Government Ga- publication of a notice with or without any omission, errors, zette office, Private Bag 13302, Windhoek, or be delivered lack of clarity or in any form whatsoever. at Justitia Building, Independence Avenue, Second Floor, Room 219, Windhoek, not later than 12h00 on the ninth 9. The subscription for the Government Gazette is working day before the date of publication of this Govern- N$4,190-00 including VAT per annum, obtainable from ment Gazette in which the advertisement is to be inserted. Solitaire Press (Pty) Ltd., corner of Bonsmara and Brahman Streets, Northern Industrial Area, P.O. Box 1155, Wind- 3. -

Environmental Scoping, Impact Assessment and Management Plan for Building Works to Alleviate Congestion at Hosea Kutako International Airport, Khomas Region, Namibia

ENVIRONMENTAL SCOPING, IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR BUILDING WORKS TO ALLEVIATE CONGESTION AT HOSEA KUTAKO INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT, KHOMAS REGION, NAMIBIA 06 December 2019 Prepared by: Prepared for: On behalf of: CONTACT DETAILS Mr Jan-Hendrik Engelbrecht Director Nexus Building Contractors (Pty) Ltd P.O. Box 150 Outjo Namibia Tel: +264 67 313770 Fax: +264 67 313768 E-mail: [email protected] Mr Scott Richards Project Manager Lithon Project Consultants (Pty) Ltd P.O. Box 40902 Ausspannplatz Windhoek Namibia Tel: +264 61 250278 Fax: +264 61 250279 E-mail: [email protected] Mr Bisey /Uirab Chief Executive Officer Namibia Airports Company P.O. Box 23061 Windhoek Namibia Tel: +264 61 2955001 Fax: +264 61 2955022 E-mail: [email protected] Dr Lima Maartens LM Environmental Consulting P.O. Box 1284 Windhoek Namibia Tel: +264 61 255750 Fax: 088 61 9004 E-mail: [email protected] Declaration: LM Environmental Consulting is an independent consulting firm with no interest in the project which is the subject matter hereof other than to fulfil the contract between the client and the consultant for delivery of specialised services as stipulated in the terms of reference. Limitation of liability: LM Environmental Consulting accept no responsibility or liability in respect of losses, damages or costs suffered or incurred, directly or indirectly, under or in connection with this report to the extent that such losses, damages, and costs are due to information provided to LM Environmental Consulting for purposes of this report that is subsequently found to be inaccurate, misleading or incomplete, or due to the acts or omissions of any person other than ourselves. -

License Contacts

License Contacts License Code Responsible License Status Date Applied Date Granted Date Expires Commodities Map References Area Parties Contact Details Office Type Communication Party Postal Address Physical Address Telephone Email Address 51522 14/2/2/1/2/ MC Pending 01 April 2017 31 March 2019 BRM Namibia,J, K, 16.8153 Ha Onganja Mining Company Renewal Khomas,Windhoek; (Pty) Ltd (100%) Otjozondjupa,Okahan dja 51523 14/2/2/1/2/ MC Pending 01 April 2017 31 March 2019 BRM Namibia,J, K, 18.1577 Ha Onganja Mining Company Renewal Khomas,Windhoek; (Pty) Ltd (100%) Otjozondjupa,Okahan dja 52604 14/2/2/1/2/ MC Pending 01 April 1994 31 March 2013 DS Picture Stone (Pty) Ltd Renewal (100%) 52605 14/2/2/1/2/ MC Pending 01 April 1994 31 March 2013 DS Picture Stone (Pty) Ltd Picture Stone (Pty) Ltd 0027-11-477- Renewal (100%) 6296 53182 14/2/2/1/2/ MC Active 01 April 1974 20 June 2021 SPS Namibia,Hardap,Malta 7.3312 Ha Daniel Matheus Laufs hohe; P Truter (100%) 53979 14/2/2/1/2/ MC Pending 01 April 2017 31 March 2019 BRM Namibia,K, 17.3954 Ha Robert Guy Carr (100%) Renewal Khomas,Windhoek 55669 14/2/2/1/2/ MC Active 22 March 1983 14 June 2020 IM Namibia Mineral Development Company (Pty) Ltd (100%) 55926 14/2/2/1/2/ MC Active 22 March 1983 14 June 2020 IM Namibia Mineral Development Company (Pty) Ltd (100%) 55927 14/2/2/1/2/ MC Active 22 March 1983 14 June 2020 IM Namibia Mineral Namibia Mineral PO Box 24046, 28 Heinitzburg Street, 237055 [email protected] Development Company Development Company Windhoek, Khomas, Windhoek, Khomas, m.na (Pty) Ltd (100%) -

The Windhoek Structure Plan

THE WINDHOEK STRUCTURE PLAN WINDHOEK MUNICIPALITY OCTOBER 1996 THE WINDHOEK STRUCTURE PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Town Planning Goals 2. Council's Vision 3. Objectives 4. Background to the City 5. The City Centre 6. Water Supply 7. Population Growth 8. Urbanisation 9. Municipal Area & Area of Expansion 10. Influence of Land Transport Routes 11. Linear Pattern 12. Common Trend 13. Benefits of the Linear Model 14. The Choice 15. Business Enterprise Locations 16. Retail Hierarchy 17. Guidelines for Suburban Business Development 18. Public Transport 19. Infrastructure 20. Housing 21. Sustainable Development 22. Recreation and the Environment 23. Rural Periphery 24. Finance 25. Regional Extension 26. Summary of Significant Statements 27. Structure for Strategies 28. Council Resolution 29. References PLANS Plan 1: Windhoek-Okahandja Urban Corridor Plan 2: Windhoek Guide Plan P/1700/S Rev.4 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Simple Sustainability Criteria ASSOCIATED DOCUMENTS 1. Development Potential of the Northern Peri-urban Areas of Windhoek (Brakwater) 2. 1993 Update of the Greater Windhoek Transportation Study 1. TOWN PLANNING GOALS Town Planning has as a general goal the aim of promoting the continued co-ordinated and harmonious development of Windhoek in such a way as will most effectively tend to promote health, safety, order, amenity, convenience and general welfare, as well as efficiency and cost effectiveness in the process of development, the attraction of new investment and the improvement of communications. To contribute its part towards the mission of Council, this report seeks to anticipate and draw Council's attention to trends and changes in urban development which may need to be addressed and to advise Council on plans and guidelines which may be recommended to handle the physical planning of land use and urbanisation. -

A Publication Of

HOUSING Property Diary https://twitter.com/TheNamibian A Publication of https://www.facebook.com/TheNamibianNewspaper 28 February 2017 2 Housing & Property Diary Serenity at Omakondo bricks introduces smart build • CHARMAINE and how they can help us NGATJIHEUE to achieve our goals,” said Jericho Heights Nghoshi. MAKONDO Nghoshi said their task is OST people lead such busy lives that all Bricks has not only to make bricks but they want is time away from the hustle and introduced a also to venture into different bustle of their reality. Onew product called the products that supplement MWell, many people are craving for a holiday early Omakondo smart build brickmaking. in the year not realising that your home can be your meant to assist low-income “Our chain of products holiday. earners who want to build include designing business Against this backdrop, newly built Jericho Heights affordable housing. plans for our customers, Omakondo bricks staff members busy at work. Photo contributed. situated at Elisenheim, brings serenity and peace Tomas Nghoshi, guiding them in their whilst providing ample security. managing member construction projects, build lasting structures seeks to provide quality those who seek them,” he Sited close to Brakwater, an area that is 10km on of Omakondo bricks making bricks and ensuring like the great wall of service to its customers. said. the outskirts of Windhoek, one’s desire to be away reiterated that Omakondo that the structures are China or the pyramids of The company serves The company has from the reality in the city is a short drive away with Bricks will be able to assist durable.