A Summary of Existing Research on Low-Head Dam Removal Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1996 Military Customer Satisfaction Survey

2010 CIVIL WORKS PROGRAMS CUSTOMER SATISFACTION SURVEY July 2011 This report prepared by: Linda Peterson, CECW Survey Manager US Army Engineer District, Mobile CESAM-PM-I 109 ST Joseph St Mobile, AL 36602 Phone (251) 694-3848 CONTENTS Page Executive Summary ………………………………………………………... 1 Section 1: Introduction 1.1 Background ……………………………..…………………………..….. 3 1.2 Survey Methodology …………………..……………………………..... 4 Section 2: Results of 2010 Survey 2.1 Customer Demographics ……………………………………………… 5 2.2 Survey Items and Scales …………………………….……………...... 12 2.3 Customer Comments ……………………………….....…..………….. 15 Section 3: Comparison of Ratings by Customer Subgroups 3.1 Ratings by Respondent Classification……….…………..…..........… 19 3.2 Ratings by Business Line.………………….……….…………....…… 21 3.3 Ratings by Project Phase ………………….……………………......... 24 3.4 Ratings By Survey Year ………….……………………………...……. 26 Section 4: Summary ………….………………………..………...…….…... 29 Tables & Figures Table 1: Respondent Classification........................................................ 6 Table 2: Primary Business Lines ……..…….……….……...……..……... 8 Table 3: ‘Other’ Business Lines..…….……….………...………....……… 8 Table 4: Project Phases ………………………....………………………... 9 Table 5: Corps Divisions..…………………..……..................………....... 10 Table 6: Corps Districts…......................................................………….. 11 Table 7: Survey Scales .………...........………………....…….…….......... 13 Table 8: Item Ratings …...………..........……………………....….………. 14 Table 9: Item Comments ..………………..………..…………..…..……… 16 Table -

NGPF's 2021 State of Financial Education Report

11 ++ 2020-2021 $$ xx %% NGPF’s 2021 State of Financial == Education Report ¢¢ Who Has Access to Financial Education in America Today? In the 2020-2021 school year, nearly 7 out of 10 students across U.S. high schools had access to a standalone Personal Finance course. 2.4M (1 in 5 U.S. high school students) were guaranteed to take the course prior to graduation. GOLD STANDARD GOLD STANDARD (NATIONWIDE) (OUTSIDE GUARANTEE STATES)* In public U.S. high schools, In public U.S. high schools, 1 IN 5 1 IN 9 $$ students were guaranteed to take a students were guaranteed to take a W-4 standalone Personal Finance course standalone Personal Finance course W-4 prior to graduation. prior to graduation. STATE POLICY IMPACTS NATIONWIDE ACCESS (GOLD + SILVER STANDARD) Currently, In public U.S. high schools, = 7 IN = 7 10 states have or are implementing statewide guarantees for a standalone students have access to or are ¢ guaranteed to take a standalone ¢ Personal Finance course for all high school students. North Carolina and Mississippi Personal Finance course prior are currently implementing. to graduation. How states are guaranteeing Personal Finance for their students: In 2018, the Mississippi Department of Education Signed in 2018, North Carolina’s legislation echoes created a 1-year College & Career Readiness (CCR) neighboring state Virginia’s, by which all students take Course for the entering freshman class of the one semester of Economics and one semester of 2018-2019 school year. The course combines Personal Finance. All North Carolina high school one semester of career exploration and college students, beginning with the graduating class of 2024, transition preparation with one semester of will take a 1-year Economics and Personal Finance Personal Finance. -

I:Jlsifr.Jm COMMON: Congressmen to Be Notified: Fort Koshkonong - May (Eli) House Site Sen

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Wisconsin COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Jefferson INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) i:jLSifr.jm COMMON: Congressmen to be notified: Fort Koshkonong - May (Eli) House Site Sen. William Proxmire AND/OR HISTORIC: Sen. Gaylord A. Nelson Rep. Robert W. Kastenmeier (2nd :i:iiiiiiiiiiiiiiii STREET AND NUMBER: 407 Milwaukee Avenue East CITY OR TOWN: . Fort Atkins on STATE COUNTY: Wisconsin 55 Jefferson 055 CATEGORY »/» OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) z Q District Q Building D Public Public Acquisition: n Occupied Yes: [X Restricted o 50 Site Q Structure XX Private Q In Process C8 Unoccupied Q Unrestricted D Object D Both [~~1 Being Considered g] preservation work in progress a NO u PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) ID C~| Agricultural | | Government D Pork 1 1 Transportation QQ Comments a: Q Commercial D Industrial I I Private Residence HD Other (Specify) Plans for Q Educational I I Military I I Religious Custodial adaptive us<- in progress ts> Q Entertainment I I Museum I I .Scientific OWNER'S NAME: -Pert—Atk-iffcsoa- His tor ica1 - Soc±<rty <t UJ STREET AND NUMBER: LU 409 Merchant Avenue IX) CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Fort Atkinson Wisconsin COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Jefferson County Courthouse STREET AND NUMBER: Cl TY OR TOWN: Jefferson Wisconsin TITLE OF SURVEY: Wisconsin Inventory of Historic Buildings and Sites DATE OF SURVEY: 1971 Q Federal gj state DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: State Historical Society of Wisconsin STREET AND NUMBER: 816 State Street CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Madison Wisconsin (Check One) Excellent §£] Good Q] Fair | | Deteriorated [~~| Ruins | | Unexposed CONDITION (Check One; fC/iec/c OneJ Altered Q Unaltered Moved |X1 Original Site A substantial, .sound, well-maintained 2f story Victorian house, built of cream-colored brick in<l864p the May House stands on the site^bf a portion of the original Port Koshkonong. -

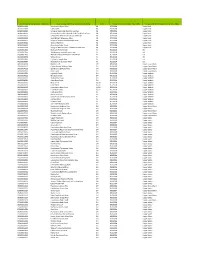

12 Digit HUC Subwatersheds in Designated 8 Digit Focus

HUC_12 (NCGC Version Date: Feb 2009) HU_12_NAME (NCGC Version Date: Feb 2009) STATES HU8 (USGS: Version Date: Nov 2008) HU_8_NAME (USGS Version Date: Nov 2008) 040302010401 Headwaters Grand River WI 07090001 Upper Rock 040302010901 Silver Creek WI 07090001 Upper Rock 040302030201 Village of Rosendale‐Fond Du Lac River WI 07090001 Upper Rock 040302030202 Sevenmile Creek‐East Branch of the Fond Du Lac River WI 07090001 Upper Rock 040400030201 Headwaters West Branch Milwaukee River WI 07090001 Upper Rock 040400030203 West Branch Milwaukee River WI 07090001 Upper Rock 040400030207 Village of Kewaskum‐Milwaukee River WI 07090001 Upper Rock 040400030301 Town of Richfield WI 07090001 Upper Rock 040400030302 Cedar Lake‐Cedar Creek WI 07090001 Upper Rock 040400030401 Village of Menomonee Falls‐Menomonee River WI 07090001 Upper Rock 040500011601 Rivir Lake‐Forker Creek IN 05120104 Eel 040500011602 Winebrenner Branch‐Carrol Creek IN 05120104 Eel 040500011604 Muncie Lake‐South Branch Elkhart River IN 05120104 Eel 041000030706 Willow Creek IN 05120104 Eel 041000030805 Ely Run‐St Joseph River IN 05120104 Eel 041000030806 Becketts Run‐St Joseph River IN 05120104 Eel 041000040101 Muddy Creek OH 05080001 Upper Great Miami 041000040102 Center Branch St Marys River OH 05080001 Upper Great Miami 041000040103 East Branch St Marys River OH 05080001 Upper Great Miami 041000040104 Kopp Creek OH 05080001 Upper Great Miami 041000040202 Eightmile Creek OH 05120101 Upper Wabash 041000040203 Blierdofer Ditch OH 05120101 Upper Wabash 041000040204 Twelvemile Creek -

1996 Military Customer Satisfaction Survey

2009 CIVIL WORKS PROGRAMS CUSTOMER SATISFACTION SURVEY July 2010 This report prepared by: Linda Peterson, CECW Survey Manager US Army Engineer District, Mobile CESAM-PM-I 109 ST Joseph St Mobile, AL 36602 Phone (251) 694-3848 CONTENTS Page # Executive Summary ………………………………………….……... 1 Section 1: Introduction 1.1 Background …………………………..……………..………..…. 3 1.2 Survey Methodology …………..…………………….………..... 3 Section 2: Results of 2009 Survey 2.1 Customer Demographics …………………………………….... 4 2.2 Survey Items and Scales …………………………….……....... 9 2.3 Customer Comments ……………………………….....……….. 12 Section 3: Comparison of Ratings by Customer Subgroups 3.1 Ratings by Business Line.………………….………..…….…… 16 3.2 Ratings by Project Phase ………………….……….………….. 18 3.3 Ratings By Survey Year ………….…………………………….. 20 Section 4: Summary …………….…………………...……..…….… 22 List of Tables & Figures Table 1: Primary Business Lines ……..…….……….…………..... 6 Table 2: ‘Other’ Service Areas..…….……….………...…….…….. 6 Table 3: Project Phases ………………………………………..…... 7 Table 4: Corps Divisions..……………………..............………....... 7 Table 5: Corps Districts…............................................………….. 8 Table 6: Satisfaction Scales .………...........………………….…… 9 Table 7: Item Ratings …...………...........……………………...…... 11 Table 8: Item Comments ..………………..……………..……….… 13 Table 9: Additional Comments …......…..………….…………….... 13 Table 10: Ratings by Business Line ……..………………………... 17 Table 11: Ratings by Project Phase ….………….….................... 18 Table 12: Customers by Business Line & Year…....................... -

Official Wisconsin Travel Guide 3 Northwest

TM OFFICIAL TRAVEL GUIDE Welcome Welcome to Wisconsin! As Governor it is my very special pleasure to welcome you to the great state of Wisconsin. From the Great Lakes to the mighty Mississippi Contents and the land in-between, we are home to a vast 2 Before You Begin landscape of beauty that includes woods, waters, 3 Region Map prairies, agriculture and cityscapes. In Wisconsin, 4 Northwest you will find small towns and back-roads filled with 16 Northeast charming hidden gems and deep history connected 28 East Central to nature. Our resort communities offer a relaxing 36 Central oasis while our urban cities pulse with excitement 42 Southwest 50 South Central and take fun to the next level. 64 Southeast Use this guide as your starting point to plan a 75 Index to Attractions Wisconsin getaway that will provide many fond 77 Index to Cities memories and adventures. And regardless of where 78 Tourism Contacts you choose to spend your vacation in Wisconsin, our special brand of warm hospitality is waiting for you. This publication was produced by the Enjoy! Wisconsin Department of Tourism, Stephanie Klett, Secretary. Published June, 2011 Wisconsin Department of Tourism 201 W. Washington Avenue P.O. Box 8690 Madison, WI 53707-8690 608/266-2161 800/432-8747 www.travelwisconsin.com Scott Walker Governor Before you begin... Travel How to use this guide Historical, heritage Green The Original Wisconsin Travel Guide and wildlife markers divides the state into seven color- There are nearly 500 Historical Wisconsin coded regions. If you know the region Markers placed along the state’s high- Tourism is big business in into which you’re traveling, follow the ways and byways. -

Svbordinate Lodges, I.O.O.F

DIRECTORY OF SVBORDINATE LODGES, I.O.O.F. Class HS5ia. Book . T^S Copyright N° COPYRIGHT DEPOSIT DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF THOMAS WILDEY THE FOUNDER OF THE NDEPENDENT ORDER OF ODD FELLOWS ON THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA PRICE, $1.SO NET ^5?is^-^^^ DIRECTORY Subordinate lodges OF THE INDEPENDENT ORDER OF ODD FELLOWS ON THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA COMPILED AND, PUBLISHED BY GEORGE H. FULLER. GRAND SECRETARY. OF MASSACHUSETTS. THE GRAND LODGe! I. O. O. FM S15 TREMONT STREET. BOSTON 1913 Copyright. 1913. by George H. Fuller THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Caustic-Claflin Company, Printers harvard Square Cambridge, Massachusetts ©CJ.A347588 It PREFACE THIS book contains the name, number and location of approximately 17,500 Subordinate Lodges of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows on the Conti- nent of North America, revised to March 20, 1913. The copy was furnished by the Grand Secretaries of the fifty- six Grand Lodges in the United States of America and Dominion of Canada. It is the purpose of the Directory to aid lodges in com- municating one with another. A message transmitted by mail as first-class matter, bearing the name, number and location of any lodge, will be delivered without additional address on the part of the writer. For example, a letter addressed to California Lodge, No. 1, I.O.O.F., San Fran- cisco, California, will be delivered to said lodge, the Post- master at San Francisco supplying the necessary informa- tion as to post-office box or street address of the lodge or Recording Secretary thereof. -

Corn Moon Migrations: Ho-Chunk Belonging, Removal, and Return in the Early Nineteenth-Century Western Great Lakes

Corn Moon Migrations: Ho-Chunk Belonging, Removal, and Return in the Early Nineteenth-Century Western Great Lakes By Libby Rose Tronnes A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN MADISON 2017 Date of final oral examination: 12/13/2017 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Susan L. Johnson, Professor, History William Cronon, Professor, History John Hall, Associate Professor, History Stephen Kantrowitz, Professor, History Larry Nesper, Professor, Anthropology and American Indian Studies ProQuest Number:10690192 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10690192 Published by ProQuest LLC ( 2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 © Copyright Libby Rose Tronnes 2017 All Rights Reserved i Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………….ii Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………..vi List of Figures …………………………………………………………………………..………viii -

When You're Having Fun, We're Having Fun

WHEN YOU’RE HAVING FUN, WE’RE HAVING FUN. 2016-17 WISCONSIN FALL/WINTER EVENT GUIDE 53 Apostle Islands, Bayfield Brown Deer Golf Course, Milwaukee WELCOME! Welcome to the great state of Wisconsin! As the days get warmer, the fun also heats up in Wisconsin. Our state offers so many fun things to do year-round. From music festivals to art fairs, water parks to Native American pow-wows, we know you’ll find lots to do during your visit. With more than 500 events, this guide offers the perfect starting point to build your own Wisconsin adventure. Regardless of where you choose to spend your vacation in Wisconsin, our special brand of warm Midwestern hospi- Charter Fishing, Racine tality is waiting for you. Enjoy your time in Wisconsin! Scott Walker s Governor Lambeau Field, Green Bay EAA AirVenture, Oshkosh Contents 2 APRIL EVENT 6 MAY EVENTS 12 JUNE EVENTS 20 JULY EVENTS 28 AUGUST EVENTS 34 SEPTEMBER EVENTS 43 ONGOING EVENTS 45 EXHIBITS 46 PERFORMING ARTS 49 TOURISM CONTACTS 53 STATE REGIONS: MAP AN EVENT Region Key: Events are labeled by their locations within the state. Use the map to find your event! NORTHWEST – NW NORTHEAST – NE CENTRAL – C SOUTHWEST – SW EAST CENTRAL – EC o TravelWisconsin.com SOUTH CENTRAL – SC Travelers discover their own SOUTHEAST – SE fun at TravelWisconsin.com. State Capitol, Madison In addition to exciting videos and exclusive content, at TravelWisconsin.com or call 800-432-8747 these features will help Order Guides guide the way. 1 Event Guide Browse 6 Campground Directory more than a thousand of The Wisconsin Association Wisconsin’s top events with of Campground Owners Fall Color Report: Plan your this guide’s two annual provides this guide of the trip to view the hues of autumn editions—spring/summer and state’s private campgrounds, with weekly updates on foliage fall/winter. -

A History of Jefferson Barracks, 1826-1860. Byron Bertrand Banta Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1981 A History of Jefferson Barracks, 1826-1860. Byron Bertrand Banta Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Banta, Byron Bertrand Jr, "A History of Jefferson Barracks, 1826-1860." (1981). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3626. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3626 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

2015-2016 Wisconsin Blue Book: Chapter 8

STATISTICS: HISTORY 675 HIGHLIGHTS OF HISTORY IN WISCONSIN History — On May 29, 1848, Wisconsin became the 30th state in the Union, but the state’s written history dates back more than 300 years to the time when the French first encountered the diverse Native Americans who lived here. In 1634, the French explorer Jean Nicolet landed at Green Bay, reportedly becoming the first European to visit Wisconsin. The French ceded the area to Great Britain in 1763, and it became part of the United States in 1783. First organized under the Northwest Ordinance, the area was part of various territories until creation of the Wisconsin Territory in 1836. Since statehood, Wisconsin has been a wheat farming area, a lumbering frontier, and a preeminent dairy state. Tourism has grown in importance, and industry has concentrated in the eastern and southeastern part of the state. Politically, the state has enjoyed a reputation for honest, efficient government. It is known as the birthplace of the Republican Party and the home of Robert M. La Follette, Sr., founder of the progressive movement. Political Balance — After being primarily a one-party state for most of its existence, with the Republican and Progressive Parties dominating during portions of the state’s first century, Wisconsin has become a politically competitive state in recent decades. The Republicans gained majority control in both houses in the 1995 Legislature, an advantage they last held during the 1969 session. Since then, control of the senate has changed several times. In 2009, the Democrats gained control of both houses for the first time since 1993; both houses returned to Republican control in 2011. -

Around the Library – Fall 2019

All AGES TWEENS Chocolate Fever Saturday, September 14, 2:00-3:30 p.m. For ages 6-13. Celebrate FALL 2019 ALL PROGRAMS ARE FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC NEW! NEW! International Chocolate Day! Play games, test your chocolate A publication of Beloit Public Library, supported in part by Friends at Beloit Public Library (FABL). Chess Club LEGO Club knowledge, vote on your 4th Saturday, 2:00 p.m. 1st Monday, 6:30-7:30 p.m. favorite chocolate bar, and September 28 | October 26 | November 30 October 7 | November 4 concoct and enjoy a fun treat. Come play a game of chess, learn the basics, or Build as a team or work on your own creation. All Music @ 605 watch others. Chess sets will be provided, but blocks are provided! Bring a camera to capture Sponsored by the BPL Foundation feel free to bring your own. Instructors will be the creations. LEGOS and Duplos cannot be The Dark Doesn’t available. For ages 8 and up. taken home. Scare Me First Brigade Band Saturday, October 12, Friday, September 13, 7:00-8:30 p.m. 2:00-3:00 p.m. This band MAKES HISTORY COME ALIVE with period brass Read for Fines Drop-In Family Historical For ages 8-13. Bring your music performed on antique instruments. Attired in uniforms All Year Long flashlight and your bravest Get a Card, Get a Prize and gowns, the musicians, color guard, and costumed ladies Reduce overdue fines by $1 for Game Day Impressions take you back to that turbulent era known as the Civil War.