Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FRANCE Figure Analysis – Displacement Related to Disasters

FRANCE Figure Analysis – Displacement Related to Disasters SUMMARY OF INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT IN 2019 France suffered from several serious and deadly disasters that caused multiple new displacements and destroyed or severely damaged many houses in 2019. IDMC estimates that there were 36 disaster events which triggered more than 16,700 new displacements. The main triggers of displacement were floods, heavy rains, storms, landslides, earthquakes and wildfires. All new displacements were caused by disasters, none by conflict or violence. France had one of the highest recorded numbers of new displacements resulting from disasters in Europe. In metropolitan France, there were 32 new displacement events, 6,157 new displacements, 674 pre-emptive evacuations and more than 800 houses destroyed. Most new displacements were caused by storms and floods. The most significant displacement event in metropolitan France was an earthquake on 11 November in Ardèche which displaced more than 2,000 people. At least 2,000 people affected by the disaster were living in a situation of displacement as of 31 December 2019. The second largest displacement event took place on 23 November and led to the evacuation of 1,655 people. The most significant displacement event in France as a whole, including Oversees France, was Cyclone Belna, which in December led to the displacement of more than 10,000 people in the overseas territory of Mayotte. IDMC was only able to identify a stock figure for the number of IDPs living in France as of 31 December for one displacement event: the earthquake in Ardèche. The true figure, however, may be larger. One of the most significant challenges of monitoring displacement in the country is the lack of time series data related to the duration of displacement and the extent to which people have reached durable solutions, such as returns or resettlement. -

France Relations the Strategic Dialogue in 1998, Soon After India's Nuclear Tests, Led to India and France Entering

India – France Relations The Strategic Dialogue in 1998, soon after India’s nuclear tests, led to India and France entering into a strategic partnership encompassing security, space, defence and civil nuclear cooperation sectors. India-France relationship enjoys bipartisan support in France and has been accorded a high priority by all the Presidents of France. With the establishment of the strategic partnership, there has been significant progress in all areas of bilateral cooperation through regular high-level exchanges at the Head of State/Head of Government levels. Indo-French relations received a boost in 2015 with high level engagements and expansion of the already strong cooperation. Prime Minister Narendra Modi paid a landmark visit to France from 09-12 April, 2015. Prime Minister Modi and President of France Mr. Francois Hollande held a bilateral meeting on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly in New York in September 2015. They again met in Paris on 30 November 2015 at the Leaders’ Event of CoP-21 (21st Session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) in Paris. There has been a significant progress in bilateral relations through regular Ministerial and official visits and exchanges in strategic areas of security, defence, nuclear energy, space as well as in other areas of bilateral cooperation like science and technology, culture, education etc. France has continued to support India’s permanent membership of the UN Security Council and multilateral export control regimes like the NSG, MTCR etc. Major Visits: President of France, Mr Francois Hollande will be paying a visit to India from 24-26 January, 2016 and will be the chief guest at the 67th Republic Day Parade. -

Post-Colonial Trends of Income Inequality in the Oversears

Post-colonial Trends of Income Inequality in The Overseas Departments of France∗ Yajna Govind y Please do not circulate. Abstract The existing socioeconomic disparities in the French overseas departments are widely acknowledged. However, despite the recurrent occurrence of protests and riots in these territories, there has sparsely been an in-depth long-run economic analysis on this assertion. This study estimates the evolution of income inequality in the four old- est French colonies, now overseas departments; La R´eunion,Guadeloupe, Martinique and Guyane since their decolonisation in 1946 until recent years. It is the first long-run comparative analysis of inequality at the regional level in France and is among the few that analyses all four overseas departments together. Drawing on a new income tax dataset put together in this paper, the results reveal a somewhat inverted-U shaped curve of inequality over the period. Interestingly, the top 10% income share is consis- tently higher in the overseas departments compared to the metropolis while top 1% stabilises at the same level as the metropolis in the recent period. Finally, it is worth noting that there are differences between the four territories. Moreover, the inequal- ity trends observed hide underlying cleavages. Using administrative data, I show that there is a \metropolitan" income premium in the overseas department. Keywords: Inequality, Top incomes, France, Overseas Departments, Taxation JEL classification: D63, H20, N30 ∗Version: 29/11/2018 yPSE, INED | Contact: [email protected] 1. Introduction The prevailing socioeconomic disparities in the French overseas departments are widely acknowledged in the local political and public sphere. -

FRANCE May 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: French Republic

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: France, May 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: FRANCE May 2007 COUNTRY Formal Name: French Republic (République Française). Short Form: France. Term for Citizen(s): Frenchman/Frenchwoman. Adjective: French. Capital: Paris. Major Cities: The country’s capital Paris, the only French city Click to Enlarge Image with more than 1 million inhabitants, has a population of 2,142,800 in the city proper (as of 2004) and 11,330,700 in the metropolitan area (2003 estimate). Greater metropolitan Paris encompasses more than 15 percent of the country’s total population. The second largest city is Marseille, a major Mediterranean seaport, with about 795,600 inhabitants. Other major cities include Lyon, an industrial center in east-central France, with 468,300 inhabitants, and the second largest metropolitan area in France, with 1,665,700 people. Further important cities include: Toulouse, 426,700, a manufacturing and European aviation center in southwestern France; Nice, 339,000, a resort city on the French Riviera; Nantes, 276,200, a seaport and shipbuilding center on the Atlantic coast; Strasbourg, 273,100, the principal French port on the Rhine River and a seat of the European parliament (in addition to Brussels); Montpellier, 244,700, a commercial and manufacturing city in southern France; and Bordeaux, 229,500, a major seaport in southwestern France and the principal exporting center for key French vineyard regions. According to the 1999 decadal census, more than 25 additional French cities had populations surpassing 100,000. Independence: July 14, Bastille Day, is France’s national holiday. Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1); Easter Monday (variable date in March or April); Labor Day (May 1); Ascension Day (Thursday, 40 days after Easter); World War II Victory Day (May 8); Bastille Day (July 14); Assumption (August 15); All Saints’ Day (November 1); Armistice Day (November 11); and Christmas Day (December 25). -

France in the South Pacific Power and Politics

France in the South Pacific Power and Politics France in the South Pacific Power and Politics Denise Fisher Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fisher, Denise, author. Title: France in the South Pacific : power and politics / Denise Fisher. ISBN: 9781922144942 (paperback) 9781922144959 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: France--Foreign relations--Oceania. Oceania--Foreign relations--France. France--Foreign relations--New Caledonia. New Caledonia--Foreign relations--France. Dewey Number: 327.44095 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2013 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii List of maps, figures and tables . ix Glossary and acronyms . xi Maps . xix Introduction . 1 Part I — France in the Pacific to the 1990s 1. The French Pacific presence to World War II . 13 2. France manages independence demands and nuclear testing 1945–1990s . 47 3 . Regional diplomatic offensive 1980s–1990s . 89 Part II — France in the Pacific: 1990s to present 4. New Caledonia: Implementation of the Noumea Accord and political evolution from 1998 . 99 5. French Polynesia: Autonomy or independence? . 179 6. France’s engagement in the region from the 1990s: France, its collectivities, the European Union and the region . -

Sugar and the Edge of France, 1800-1860

Droits and Frontières: Sugar and the Edge of France, 1800-1860 Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Yarrington, Jonna M. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 23:07:45 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/316894 DROITS AND FRONTIÈRES: SUGAR AND THE EDGE OF FRANCE, 1800-1860 by Jonna M. Yarrington ____________________________ A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2014 2 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that an accurate acknowledgment of the source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

School Divisions and Inequalities in Funding, Access to Schools and Staffing Patrice Caro

School divisions and inequalities in funding, access to schools and staffing Patrice Caro To cite this version: Patrice Caro. School divisions and inequalities in funding, access to schools and staffing. Pierre Champollion. Territorialization of education. Trend or necessity, ISTE, 2020. halshs-02780825 HAL Id: halshs-02780825 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02780825 Submitted on 4 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Chapter 1 School divisions and inequalities in funding, access to schools and staffing 1.1 Summary The French education system produces its own inequalities, in addition to those generated by the demographic, economic, cultural and social context in which it operates. How many different versions of France appear when we analyze the inequalities in the distribution of both financial and human resources by the different levels of the State and by the various local authorities, as well as the inequalities in physical accessibility (roads, for example) to high schools? Can we talk about divisions concerning -

Catholic Missionaries and the Colonial State in French Algeria, 1830-1914

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 Civilizing Settlers: Catholic Missionaries and the Colonial State in French Algeria, 1830-1914 Kyle Francis Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/558 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] CIVILIZING SETTLERS: CATHOLIC MISSIONARIES AND THE COLONIAL STATE IN FRENCH ALGERIA, 1830-1914 by KYLE FRANCIS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 © 2015 KYLE FRANCIS All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor David Troyansky ______________________ _________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor Helena Rosenblatt ______________________ _________________________________________ Date Executive Officer Professor Dagmar Herzog Professor Clifford Rosenberg Professor Megan Vaughan Professor Judith Surkis Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract CIVILIZING SETTLERS: CATHOLIC MISSIONARIES AND THE COLONIAL STATE IN FRENCH ALGERIA, 1830-1914 by Kyle Francis Advisor: Professor David Troyansky This dissertation argues that between 1830 and 1914, with increasing intensity over time, French Catholic missionaries sowed divisions among the European population of French Algeria. The French government initially welcomed missionaries to cater to religiously devout Spanish, Italian, and Maltese settlers in Algeria and to foster their loyalty to the colonial state. -

Evaluating Sustainable Development by Composite Index: Evidence from French Departments

sustainability Article Evaluating Sustainable Development by Composite Index: Evidence from French Departments Jean Bonnet 1 , Eva Coll-Martínez 2,* and Patricia Renou-Maissant 3 1 SEGGAT-CREM, Normandy University, 14032 Caen CEDEX, France; [email protected] 2 LEREPS, Sciences Po Toulouse, 31042 Toulouse CEDEX, France 3 EconomiX, Paris Nanterre University, 92001 Nanterre, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Since the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals by the United Nations, sustain- ability has been a key priority for European governments. While previous studies have investigated the associations between indicators of sustainable development, few have directly considered a multidimensional approach to assess and compare the performance of regions in terms of sustainable development. As such, a comprehensive assessment of regional sustainable performance is thus still needed. In this paper, the concept of sustainability relies on the construction of six composite indices (environment and natural resources, energy transition, sustainable mobility, economic dynamism, social cohesion and solidarity, and governance and citizenship) with the aim to provide an evaluation framework for empirically comparing the performance of the 96 metropolitan French Departments. Each dimension is explored by spatial autocorrelation analysis and Hierarchical Ascending Classifi- cation (HAC) to classify French Departments providing five different regional profiles of sustainable development. The findings make it possible to identify the strengths and weaknesses of the depart- ments in the implementation of sustainable development. This approach provides the bases for a systematic monitoring of sustainable development policies at the regional scale. Citation: Bonnet, J.; Coll-Martínez, Keywords: sustainable development; composite index; cluster analysis; spatial autocorrelation E.; Renou-Maissant, P. -

FOR the RECORDS Researching Alsace and Lorraine

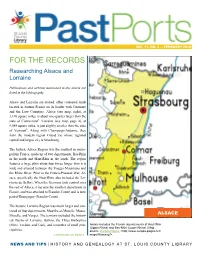

VOL. 11, NO. 2 — FEBRUARY 2018 FOR THE RECORDS Researching Alsace and Lorraine Publications and websites mentioned in this article are listed in the bibliography. Alsace and Lorraine are storied, often contested lands located in eastern France on its border with Germany and the Low Countries. Alsace (see map, right), at 3,196 square miles, is about one-quarter larger than the state of Connecticut1. Lorraine (see map, page 4), at 9,089 square miles, is just slightly smaller than the state of Vermont2. Along with Champaign-Ardenne, they form the modern region Grand Est whose regional capital and largest city is Strasbourg. The historic Alsace Region was the smallest in metro- politan France, made up of two departments, Bas-Rhin in the north and Haut-Rhin in the south. The region features a large plain about four times longer than it is wide and situated between the Vosges Mountains and the Rhine River. Prior to the Franco-Prussian War, Al- sace, specifically the Haut-Rhin, also included the Ter- ritoire de Belfort. When the Germans took control over the rest of Alsace, it became the smallest department in France, and was attached to Franche-Comté and is now part of Bourgogne- Franche-Comté. The historic Lorraine Region was much larger and con- sisted of four departments, Meurthe-et-Moselle, Meuse, Moselle, and Vosges. The territory included the histori- ALSACE cal Duchy of Lorraine, Barrois, the Three Bishoprics (Metz, Verdun, and Toul), and a number of small prin- Alsace includes the French départements of Haut-Rhin (Upper Rhine) and Bas-Rhin (Lower Rhine) | Map cipalities. -

Chapter Four

Decentralisation in France between Capacity and Constraint Alistair Cole (Cardiff University, Wales - UK) and Romain Pasquier (Institute of Political Studies, Rennes, France). Paper presented to the Political Studies Association’s Annual Conference, Cardiff 25-27 March 2013 This paper is an early output of the Leverhulme Trust’s International Network on Territorial Governance in western Europe: between Capacity and Convergence (IN - 2012-109). We thank the Trust for its support. 101 Based on vigorous cultural and political assimilationist policies (via the army, the education system and the national language), the Jacobin ideal of the “nation state”, according to which the nation is a product of the (democratic) state, has been seriously challenged these last decades (Pasquier 2012). The French state, like other European nation-states, has been confronted for some years by the dual pressure of European integration and the growing desire for autonomy on the part of sub-national political communities. As a result of the decentralisation laws of 1982-83, the evolution of EU policies and, more generally, the increasing globalization of the overall economic context, the central administrative organs of the French state have lost their monopoly on political initiative (Le Galès 1999). The French state is increasingly exposed to new economic, social and cultural logics. The growing power of local and regional authorities in the public policy process is one of the most striking features of the erosion of the Jacobin myth of the unity and indivisibility of the Republic. It provides the main object of analysis for this paper. The paper provides an overview of some of the salient features of France’s complex pattern of local and regional governance. -

France in the South Pacific Power and Politics

France in the South Pacific Power and Politics France in the South Pacific Power and Politics Denise Fisher Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fisher, Denise, author. Title: France in the South Pacific : power and politics / Denise Fisher. ISBN: 9781922144942 (paperback) 9781922144959 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: France--Foreign relations--Oceania. Oceania--Foreign relations--France. France--Foreign relations--New Caledonia. New Caledonia--Foreign relations--France. Dewey Number: 327.44095 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2013 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii List of maps, figures and tables . ix Glossary and acronyms . xi Maps . xix Introduction . 1 Part I — France in the Pacific to the 1990s 1. The French Pacific presence to World War II . 13 2. France manages independence demands and nuclear testing 1945–1990s . 47 3 . Regional diplomatic offensive 1980s–1990s . 89 Part II — France in the Pacific: 1990s to present 4. New Caledonia: Implementation of the Noumea Accord and political evolution from 1998 . 99 5. French Polynesia: Autonomy or independence? . 179 6. France’s engagement in the region from the 1990s: France, its collectivities, the European Union and the region .