Ice Age Exhibit Depicts a Unique Ecosystem, a System That Has Vigorously Clung to Life Against Sometimes Insurmountable Odds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcript for Tracks in the Snow by Wong Herbert Yee (Square Fish, an Imprint of Macmillan)

Transcript for Tracks in the Snow by Wong Herbert Yee (Square Fish, an Imprint of Macmillan) Introduction (approximately 0:00 – 5:16) Hi everyone! It's Colleen from the KU Natural History Museum, and I am so excited for today's Story Book Science. I'm so excited to read the Book Tracks in the Snow. But while we wait, Because I want to give some opportunity for folks to join us, I want to ask you a question that's related to the Book. Now, when we look at the Book cover, we see the word tracks is in the title. So what are tracks? Well, tracks are markings or impressions that animals, including humans, can leave Behind. And they leave them Behind in suBstances like snow or dirt. Alright? So, these tracks can tell us about what animals are in an area. And we can use them to identify the animals. Okay? Now, what animals do you think we can identify By their tracks? We can definitely identify animals like cottontail rabBits and mallard ducks. So I have the tracks of a cottontail rabBit and a mallard duck. So I'm going to grab those. And this is the track of a cottontail rabBit. You can see it's very oval – oops – very oval in shape. And it's very long. So this is how we can identify a cottontail rabBit, looking for this really long oval shape. So I'm going to put this down. And now, we're going to look at the track of a mallard duck. -

Gyrfalcon Diet in Central West Greenland During the Nesting Period

The Condor 105:528±537 q The Cooper Ornithological Society 2003 GYRFALCON DIET IN CENTRAL WEST GREENLAND DURING THE NESTING PERIOD TRAVIS L. BOOMS1,3 AND MARK R. FULLER2 1Boise State University Raptor Research Center, 1910 University Drive, Boise, ID 83725 2USGS Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, 970 Lusk St., Boise, ID 83706 Abstract. We studied food habits of Gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus) nesting in central west Greenland in 2000 and 2001 using three sources of data: time-lapse video (3 nests), prey remains (22 nests), and regurgitated pellets (19 nests). These sources provided different information describing the diet during the nesting period. Gyrfalcons relied heavily on Rock Ptarmigan (Lagopus mutus) and arctic hares (Lepus arcticus). Combined, these species con- tributed 79±91% of the total diet, depending on the data used. Passerines were the third most important group. Prey less common in the diet included waterfowl, arctic fox pups (Alopex lagopus), shorebirds, gulls, alcids, and falcons. All Rock Ptarmigan were adults, and all but one arctic hare were young of the year. Most passerines were ¯edglings. We observed two diet shifts, ®rst from a preponderance of ptarmigan to hares in mid-June, and second to passerines in late June. The video-monitored Gyrfalcons consumed 94±110 kg of food per nest during the nestling period, higher than previously estimated. Using a combi- nation of video, prey remains, and pellets was important to accurately document Gyrfalcon diet, and we strongly recommend using time-lapse video in future diet studies to identify biases in prey remains and pellet data. Key words: camera, diet, Falco rusticolus, food habits, Greenland, Gyrfalcon, time-lapse video. -

Nesting Behavior of Female White-Tailed Ptarmigan in Colorado

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 215 Condor, 81:215-217 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1070 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF FEMALE settling on the clutches. By lifting the hens off their WHITE-TAILED PTARMIGAN nests, we learned that eggs were laid almost immedi- ately after settling. IN COLORADO After eggs were laid, the hens remained relatively inactive until they prepared to depart from the nest. Observations of six hens in 1975 indicated that they KENNETH M. GIESEN remained on the nest for longer periods as the clutch AND approached completion. One hen depositing her sec- ond egg remained on her nest for 44 min, whereas CLAIT E. BRAUN another, depositing the fifth egg of a six-egg clutch, remained on the nest more than 280 min. Three hens remained on their nests 84 to 153 min when laying Few detailed observations on behavior of nesting their second or third eggs. Spruce Grouse also show grouse have been reported. Notable exceptions are this pattern of nest attentiveness (McCourt et al. those of SchladweiIer (1968) and Maxson (1977) 1973). who studied feeding behavior and activity patterns of Before departing from the nest, the hen began to Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) in Minnesota, and peck at vegetation and place it at the rim of the McCourt et al. ( 1973) who documented nest atten- nest, or throw it over her back. This behavior lasted tiveness of Spruce Grouse (Canachites canudensis) in 34, 40 and 64 min for three hens. Vegetation was southwestern Alberta. White-tailed Ptarmigan (Lugo- deposited on the nest at the rate of 20 pieces per pus Zeucurus) have been intensively studied in Colo- minute. -

The Climate of the Last Glacial Maximum: Results from a Coupled Atmosphere-Ocean General Circulation Model Andrew B

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 104, NO. D20, PAGES 24,509–24,525, OCTOBER 27, 1999 The climate of the Last Glacial Maximum: Results from a coupled atmosphere-ocean general circulation model Andrew B. G. Bush Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada S. George H. Philander Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, Department of Geosciences, Princeton University Princeton, New Jersey Abstract. Results from a coupled atmosphere-ocean general circulation model simulation of the Last Glacial Maximum reveal annual mean continental cooling between 4Њ and 7ЊC over tropical landmasses, up to 26Њ of cooling over the Laurentide ice sheet, and a global mean temperature depression of 4.3ЊC. The simulation incorporates glacial ice sheets, glacial land surface, reduced sea level, 21 ka orbital parameters, and decreased atmospheric CO2. Glacial winds, in addition to exhibiting anticyclonic circulations over the ice sheets themselves, show a strong cyclonic circulation over the northwest Atlantic basin, enhanced easterly flow over the tropical Pacific, and enhanced westerly flow over the Indian Ocean. Changes in equatorial winds are congruous with a westward shift in tropical convection, which leaves the western Pacific much drier than today but the Indonesian archipelago much wetter. Global mean specific humidity in the glacial climate is 10% less than today. Stronger Pacific easterlies increase the tilt of the tropical thermocline, increase the speed of the Equatorial Undercurrent, and increase the westward extent of the cold tongue, thereby depressing glacial sea surface temperatures in the western tropical Pacific by ϳ5Њ–6ЊC. 1. Introduction and Broccoli, 1985a, b; Broccoli and Manabe, 1987; Broccoli and Marciniak, 1996]. -

Ducks Nesting in Enclosed Areas and Ducks in the Pool

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ducks Nesting In Enclosed Areas and Ducks in the Pool After about 25 days of incubation, the chicks will hatch. Duck migration: The mother will lead her chicks to the water within 24 Mallards often migrate unless there is sufficient food hours after hatching. Keep children and pets away and water available throughout the year. Many from the family. migrating individuals spend their winters in the Gulf Coast and fly to the Northern U.S. and Canada in the Ducks in enclosed areas and in the pool: spring. For migrating Mallards, spring migration Your yard may be providing ducks with the ideal place begins in March. In many western states, Mallards are to build a nest. You may have vegetation and water present year-round. that provides them with resources to live and build a nest in hopes they will succeed in raising a brood. Male Mallard Tim Ludwick/USFWS Female Mallard Tim Ludwick/USFWS Territory and Breeding: Breeding season varies among individuals, locations, Here, we provide you with some suggestions when and weather. Mallards begin to defend a territory ducks have decided to make your yard a temporary about 200 yards from where the nesting takes place. home. They often defend the territory to isolate the female from other males around February-mid May. Mallards What to do to discourage nesting and swimming in build their nests between March-June and breed pools: through the beginning of August. These birds can be secretive during the breeding seasons and may nest in • When you see a pair of ducks, or a female quacking places that are not easily accessible. -

The History of Ice on Earth by Michael Marshall

The history of ice on Earth By Michael Marshall Primitive humans, clad in animal skins, trekking across vast expanses of ice in a desperate search to find food. That’s the image that comes to mind when most of us think about an ice age. But in fact there have been many ice ages, most of them long before humans made their first appearance. And the familiar picture of an ice age is of a comparatively mild one: others were so severe that the entire Earth froze over, for tens or even hundreds of millions of years. In fact, the planet seems to have three main settings: “greenhouse”, when tropical temperatures extend to the polesand there are no ice sheets at all; “icehouse”, when there is some permanent ice, although its extent varies greatly; and “snowball”, in which the planet’s entire surface is frozen over. Why the ice periodically advances – and why it retreats again – is a mystery that glaciologists have only just started to unravel. Here’s our recap of all the back and forth they’re trying to explain. Snowball Earth 2.4 to 2.1 billion years ago The Huronian glaciation is the oldest ice age we know about. The Earth was just over 2 billion years old, and home only to unicellular life-forms. The early stages of the Huronian, from 2.4 to 2.3 billion years ago, seem to have been particularly severe, with the entire planet frozen over in the first “snowball Earth”. This may have been triggered by a 250-million-year lull in volcanic activity, which would have meant less carbon dioxide being pumped into the atmosphere, and a reduced greenhouse effect. -

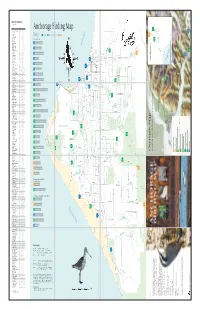

Anchorage Birding Map ❏ Common Redpoll* C C C C ❄ ❏ Hoary Redpoll R ❄ ❏ Pine Siskin* U U U U ❄ Additional References: Anchorage Audubon Society

BIRDS OF ANCHORAGE (Knik River to Portage) SPECIES SP S F W ❏ Greater White-fronted Goose U R ❏ Snow Goose U ❏ Cackling Goose R ? ❏ Canada Goose* C C C ❄ ❏ Trumpeter Swan* U r U ❏ Tundra Swan C U ❏ Gadwall* U R U ❄ ❏ Eurasian Wigeon R ❏ American Wigeon* C C C ❄ ❏ Mallard* C C C C ❄ ❏ Blue-winged Teal r r ❏ Northern Shoveler* C C C ❏ Northern Pintail* C C C r ❄ ❏ Green-winged Teal* C C C ❄ ❏ Canvasback* U U U ❏ Redhead U R R ❄ ❏ Ring-necked Duck* U U U ❄ ❏ Greater Scaup* C C C ❄ ❏ Lesser Scaup* U U U ❄ ❏ Harlequin Duck* R R R ❄ ❏ Surf Scoter R R ❏ White-winged Scoter R U ❏ Black Scoter R ❏ Long-tailed Duck* R R ❏ Bufflehead U U ❄ ❏ Common Goldeneye* C U C U ❄ ❏ Barrow’s Goldeneye* U U U U ❄ ❏ Common Merganser* c R U U ❄ ❏ Red-breasted Merganser u R ❄ ❏ Spruce Grouse* U U U U ❄ ❏ Willow Ptarmigan* C U U c ❄ ❏ Rock Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ White-tailed Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ Red-throated Loon* R R R ❏ Pacific Loon* U U U ❏ Common Loon* U R U ❏ Horned Grebe* U U C ❏ Red-necked Grebe* C C C ❏ Great Blue Heron r r ❄ ❏ Osprey* R r R ❏ Bald Eagle* C U U U ❄ ❏ Northern Harrier* C U U ❏ Sharp-shinned Hawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Northern Goshawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Red-tailed Hawk* U R U ❏ Rough-legged Hawk U R ❏ Golden Eagle* U R U ❄ ❏ American Kestrel* R R ❏ Merlin* U U U R ❄ ❏ Gyrfalcon* R ❄ ❏ Peregrine Falcon R R ❄ ❏ Sandhill Crane* C u U ❏ Black-bellied Plover R R ❏ American Golden-Plover r r ❏ Pacific Golden-Plover r r ❏ Semipalmated Plover* C C C ❏ Killdeer* R R R ❏ Spotted Sandpiper* C C C ❏ Solitary Sandpiper* u U U ❏ Wandering Tattler* u R R ❏ Greater Yellowlegs* -

"The Who Sings My Generation" (Album)

“The Who Sings My Generation”—The Who (1966) Added to the National Registry: 2008 Essay by Cary O’Dell Original album Original label The Who Founded in England in 1964, Roger Daltrey, Pete Townshend, John Entwistle, and Keith Moon are, collectively, better known as The Who. As a group on the pop-rock landscape, it’s been said that The Who occupy a rebel ground somewhere between the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, while, at the same time, proving to be innovative, iconoclastic and progressive all on their own. We can thank them for various now- standard rock affectations: the heightened level of decadence in rock (smashed guitars and exploding drum kits, among other now almost clichéd antics); making greater use of synthesizers in popular music; taking American R&B into a decidedly punk direction; and even formulating the idea of the once oxymoronic sounding “rock opera.” Almost all these elements are evident on The Who’s debut album, 1966’s “The Who Sings My Generation.” Though the band—back when they were known as The High Numbers—had a minor English hit in 1964 with the singles “I’m the Face”/”Zoot Suit,” it wouldn’t be until ’66 and the release of “My Generation” that the world got a true what’s what from The Who. “Generation,” steam- powered by its title tune and timeless lyric of “I hope I die before I get old,” “Generation” is a song cycle worthy of its inclusive name. Twelve tracks make up the album: “I Don’t Mind,” “The Good’s Gone,” “La-La-La Lies,” “Much Too Much,” “My Generation,” “The Kids Are Alright,” “Please, Please, Please,” “It’s Not True,” “The Ox,” “A Legal Matter” and “Instant Party.” Allmusic.com summarizes the album appropriately: An explosive debut, and the hardest mod pop recorded by anyone. -

(RESULTS of NATION-WIDE SURVEY) -- January 29, 1939 A

INFORMATION FOR TEE - ’ Chited StatecDepartment of Agridbe . I For Jan. 29 pspers WASHINGTON,D. C. 5,OOC,OOO BIG GM ANI- IN THE U. S. Biological Survey Beports Results of First Nation-Wide Inventory The first nation-wide attempt to determine the number of big-game animals in the United States showed more than 5 million, reports the Bureau of Biological Survey, U. S. Department of Agriculture. The survey - conducted in 1937 by the Bureau with cooperation from the National Park Service, the Boreet Service, State game and conservation commission8 and other well-informed agencies and individuals -- covered deer, elk, antelope, buffalo, moose, mountain goat, bighorn sheep, peccary, bears, caribou, and exotic European wild boars. The inventory did not include animals in captivity. Deer numbered more than 4,500,OOO. Michigan end Pennsylvania led in white- California had 450,000 tailed deer with approximately 800,000 in each State. * mule and black-tailed deer. Elk in the country totalled 165,000; moose, 13,000; antelope, 130,000; bighorn sheep, 17,000; black bear, 81,000; grizzly bear, 1,100; and buffalo, 4,100. There were 43,000 peccaries and 700 European wild boars. Data for 2 or more years, the Division of Wildlife Reeearoh of the Bureau of Biological survey points out , are required before definite conclusions can be drawn on recent trends In big-game numbers. Accounts of animal numbers published some years ego, however, provide the Division with some basis for comparison. Antelope, once thought facing extinction, incroasad about 500 percent from 1924 to 1937. The number of bighorn sheep, on the other haad, dropped from 28 000 (an estimate made by E. -

4-H-993-W, Wildlife Habitat Evaluation Food Flash Cards

Purdue extension 4-H-993-W Wildlife Habitat Evaluation Food Flash Cards Authors: Natalie Carroll, Professor, Youth Development right, it goes in the “fast” pile. If it takes a little and Agricultural Education longer, put the card in the “medium” pile. And if Brian Miller, Director, Illinois–Indiana Sea Grant College the learner does not know, put the card in the “no” Program Photos by the authors, unless otherwise noted. pile. Concentrate follow-up study efforts on the “medium” and “no” piles. These flash cards can help youth learn about the foods that wildlife eat. This will help them assign THE CONTEST individual food items to the appropriate food When youth attend the WHEP Career Development categories and identify which wildlife species Event (CDE), actual food specimens—not eat those foods during the Foods Activity of the pictures—will be displayed on a table (see Wildlife Habitat Evaluation Program (WHEP) Figure 1). Participants need to identify which contest. While there may be some disagreement food category is represented by the specimen. about which wildlife eat foods from the category Participants will write this food category on the top represented by the picture, the authors feel that the of the score sheet (Scantron sheet, see Figure 2) and species listed give a good representation. then mark the appropriate boxes that represent the wildlife species which eat this category of food. The Use the following pages to make flash cards by same species are listed on the flash cards, making it cutting along the dotted lines, then fold the papers much easier for the students to learn this material. -

Europe's Huntable Birds a Review of Status and Conservation Priorities

FACE - EUROPEAN FEDERATIONEurope’s FOR Huntable HUNTING Birds A Review AND CONSERVATIONof Status and Conservation Priorities Europe’s Huntable Birds A Review of Status and Conservation Priorities December 2020 1 European Federation for Hunting and Conservation (FACE) Established in 1977, FACE represents the interests of Europe’s 7 million hunters, as an international non-profit-making non-governmental organisation. Its members are comprised of the national hunters’ associations from 37 European countries including the EU-27. FACE upholds the principle of sustainable use and in this regard its members have a deep interest in the conservation and improvement of the quality of the European environment. See: www.face.eu Reference Sibille S., Griffin, C. and Scallan, D. (2020) Europe’s Huntable Birds: A Review of Status and Conservation Priorities. European Federation for Hunting and Conservation (FACE). https://www.face.eu/ 2 Europe’s Huntable Birds A Review of Status and Conservation Priorities Executive summary Context Non-Annex species show the highest proportion of ‘secure’ status and the lowest of ‘threatened’ status. Taking all wild birds into account, The EU State of Nature report (2020) provides results of the national the situation has deteriorated from the 2008-2012 to the 2013-2018 reporting under the Birds and Habitats directives (2013 to 2018), and a assessments. wider assessment of Europe’s biodiversity. For FACE, the findings are of key importance as they provide a timely health check on the status of In the State of Nature report (2020), ‘agriculture’ is the most frequently huntable birds listed in Annex II of the Birds Directive. -

Pleistocene Mammals from Extinction Cave, Belize

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Pleistocene Mammals From Extinction Cave, Belize Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2018-0178.R3 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 04-May-2019 Author: Complete List of Authors: Churcher, C.S.; University of Toronto, Zoology Central America, Pleistocene, Fauna, Vertebrate Palaeontology, Keyword: Limestone cave Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Not applicableDraft (regular submission) Issue? : https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjes-pubs Page 1 of 43 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 1 PLEISTOCENE MAMMALS FROM EXTINCTION CAVE, BELIZE 2 by C.S. CHURCHER1 Draft 1Department of Zoology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario Canada M5S 2C6 and 322-240 Dallas Rd., Victoria, British Columbia, Canada V8V 4X9 (corresponding address): e-mail [email protected] https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjes-pubs Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 43 2 4 5 ABSTRACT. A small mammalian fauna is recorded from Extinction Cave (also called Sibun 6 Cave), east of Belmopan, on the Sibun River, Belize, Central America. The animals recognized 7 are armadillo (†Dasypus bellus), American lion (†Panthera atrox), jaguar (P. onca), puma or 8 mountain lion (Puma concolor), Florida spectacled bear (†Tremarctos floridanus), javelina or 9 collared peccary (Pecari tajacu), llama (Camelidae indet., ?†Palaeolama mirifica), red brocket 10 deer (Mazama americana), bison (Bison sp.) and Mexican half-ass (†Equus conversidens), and 11 sabre-tooth cat († Smilodon fatalis) may also be represented (‘†’ indicates an extinct taxon). 12 Bear and bison are absent from the region today. The bison record is one of the more southernly 13 known. The bear record is almost the mostDraft westerly known and a first for Central America.