Using Predator Exclosures to Protect Ground Nests from Red Fox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcript for Tracks in the Snow by Wong Herbert Yee (Square Fish, an Imprint of Macmillan)

Transcript for Tracks in the Snow by Wong Herbert Yee (Square Fish, an Imprint of Macmillan) Introduction (approximately 0:00 – 5:16) Hi everyone! It's Colleen from the KU Natural History Museum, and I am so excited for today's Story Book Science. I'm so excited to read the Book Tracks in the Snow. But while we wait, Because I want to give some opportunity for folks to join us, I want to ask you a question that's related to the Book. Now, when we look at the Book cover, we see the word tracks is in the title. So what are tracks? Well, tracks are markings or impressions that animals, including humans, can leave Behind. And they leave them Behind in suBstances like snow or dirt. Alright? So, these tracks can tell us about what animals are in an area. And we can use them to identify the animals. Okay? Now, what animals do you think we can identify By their tracks? We can definitely identify animals like cottontail rabBits and mallard ducks. So I have the tracks of a cottontail rabBit and a mallard duck. So I'm going to grab those. And this is the track of a cottontail rabBit. You can see it's very oval – oops – very oval in shape. And it's very long. So this is how we can identify a cottontail rabBit, looking for this really long oval shape. So I'm going to put this down. And now, we're going to look at the track of a mallard duck. -

Ducks Nesting in Enclosed Areas and Ducks in the Pool

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ducks Nesting In Enclosed Areas and Ducks in the Pool After about 25 days of incubation, the chicks will hatch. Duck migration: The mother will lead her chicks to the water within 24 Mallards often migrate unless there is sufficient food hours after hatching. Keep children and pets away and water available throughout the year. Many from the family. migrating individuals spend their winters in the Gulf Coast and fly to the Northern U.S. and Canada in the Ducks in enclosed areas and in the pool: spring. For migrating Mallards, spring migration Your yard may be providing ducks with the ideal place begins in March. In many western states, Mallards are to build a nest. You may have vegetation and water present year-round. that provides them with resources to live and build a nest in hopes they will succeed in raising a brood. Male Mallard Tim Ludwick/USFWS Female Mallard Tim Ludwick/USFWS Territory and Breeding: Breeding season varies among individuals, locations, Here, we provide you with some suggestions when and weather. Mallards begin to defend a territory ducks have decided to make your yard a temporary about 200 yards from where the nesting takes place. home. They often defend the territory to isolate the female from other males around February-mid May. Mallards What to do to discourage nesting and swimming in build their nests between March-June and breed pools: through the beginning of August. These birds can be secretive during the breeding seasons and may nest in • When you see a pair of ducks, or a female quacking places that are not easily accessible. -

4-H-993-W, Wildlife Habitat Evaluation Food Flash Cards

Purdue extension 4-H-993-W Wildlife Habitat Evaluation Food Flash Cards Authors: Natalie Carroll, Professor, Youth Development right, it goes in the “fast” pile. If it takes a little and Agricultural Education longer, put the card in the “medium” pile. And if Brian Miller, Director, Illinois–Indiana Sea Grant College the learner does not know, put the card in the “no” Program Photos by the authors, unless otherwise noted. pile. Concentrate follow-up study efforts on the “medium” and “no” piles. These flash cards can help youth learn about the foods that wildlife eat. This will help them assign THE CONTEST individual food items to the appropriate food When youth attend the WHEP Career Development categories and identify which wildlife species Event (CDE), actual food specimens—not eat those foods during the Foods Activity of the pictures—will be displayed on a table (see Wildlife Habitat Evaluation Program (WHEP) Figure 1). Participants need to identify which contest. While there may be some disagreement food category is represented by the specimen. about which wildlife eat foods from the category Participants will write this food category on the top represented by the picture, the authors feel that the of the score sheet (Scantron sheet, see Figure 2) and species listed give a good representation. then mark the appropriate boxes that represent the wildlife species which eat this category of food. The Use the following pages to make flash cards by same species are listed on the flash cards, making it cutting along the dotted lines, then fold the papers much easier for the students to learn this material. -

Bobcats/Town Forest

artford onservation ommission H C C The Hartford Conservation Commission (HCC) invites you to The HCC became custodians of the Hartford Town Forest enjoy a hidden jewel, the Hartford Town Forest. What makes it (HTF) in 1997. We strive to balance three forestry so special? It is one of the largest parcels of undeveloped land objectives: in Hartford and is home to numerous animals from secretive amphibians to large mammals; even wide-ranging bear and • Forest Products: to sustainably grow and harvest moose pass through the forest. trees while respecting the natural communities • WildliFe: to provide and enhance diverse habitats for The Hartford Town Forest is a 423-acre parcel that abuts the native wildlife C 142-acre Hurricane Forest Wildlife Refuge (HFWR). Both • recreation: to promote recreation that will a) parcels are almost entirely forested and collectively contain ensure all users’ safety, and b) ‘tread lightly’ on the three old reservoirs, several miles of recreational trails, seasonal forest and its wildlife and permanent streams, varied topography, and diverse wildlife This newsletter focuses on the HTF. We’ll review what the O habitats. The Parks and Recreation Commission oversees the HFWR, with its recreation and wildlife protection focus. The HCC is doing to manage the HTF and what we can all do to HCC manages the more remote Hartford Town Forest. be good stewards of this special place. N 2010 HCC EvEnts CalEndar April 17, Saturday Vernal Pool Walk, 10:00 a.m. — noon, Hartford Town Forest* April 22, Thursday Earth Day, Kim Royar (VT Fish and Wildlife) Lecture on Bobcats and the Linking Lands Alliance S presents its Wildlife Habitat Map, 7 p.m., Vermont Institute of Natural Science (VINS), Quechee April 24–May 1 Green-Up Hartford Days, green-up bags available at Municipal Office* May 1, Saturday Green-Up Day/Arbor Day Celebration, 9:00 a.m. -

Tribal Wildlife Grant Final Report Makah Cougar and Bobcat Research Grant: F12AP00260

Tribal Wildlife Grant Final Report Makah Cougar and Bobcat Research Grant: F12AP00260 Prepared by: Shannon Murphie and Rob McCoy 1 INTRODUCTION Mountain lions or cougars (Puma concolor) and bobcats (Lynx rufus) are both native mammals of the family Felidae. Mountain lions are large solitary cats with the greatest range of any large wild terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere (Iriarte et al. 1990). Bobcats are also solitary cats that range from southern Canada to northern Mexico, including most of the continental United States. Both species are predators and as such play a prominent role in Native American mythology and culture due to their perceived attributes such as grace, strength, eyesight, and hunting ability. Similar to other Native American Tribes, predators have played a key role in the culture and ceremonies of the Makah people. Gray wolves (Canis lupus), black bear (Ursus americanus), cougars, and bobcats all are important components of Makah culture both historically and in contemporary times. For example, black bears and gray wolves both represented important clans in Makah history. Gray wolves exhibited cooperative behavior that provided guidelines for human behavior and “Klukwalle,” or wolf ritual, was a secret society that required a 6 day initiation period (G. Arnold, personal communication). Wolf hides were also used in dance and costume regalia. Bear hides were worn by men of status (Chapman 1994) and as regalia during whale hunts (G. Ray, personal communication). Cougars and bobcats play a smaller, but still important role in Makah history and contemporary culture. During naming ceremonies a Makah name is given which best reflects an individual, often an animal such as the mountain lion is used as it represents intelligence and power. -

2019 Waterfowl Population Status Survey

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Waterfowl Population Status, 2019 Waterfowl Population Status, 2019 August 19, 2019 In the United States the process of establishing hunting regulations for waterfowl is conducted annually. This process involves a number of scheduled meetings in which information regarding the status of waterfowl is presented to individuals within the agencies responsible for setting hunting regulations. In addition, the proposed regulations are published in the Federal Register to allow public comment. This report includes the most current breeding population and production information available for waterfowl in North America and is a result of cooperative eforts by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS), various state and provincial conservation agencies, and private conservation organizations. In addition to providing current information on the status of populations, this report is intended to aid the development of waterfowl harvest regulations in the United States for the 2020–2021 hunting season. i Acknowledgments Waterfowl Population and Habitat Information: The information contained in this report is the result of the eforts of numerous individuals and organizations. Principal contributors include the Canadian Wildlife Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, state wildlife conservation agencies, provincial conservation agencies from Canada, and Direcci´on General de Conservaci´on Ecol´ogica de los Recursos Naturales, Mexico. In addition, several conservation organizations, other state and federal agencies, universities, and private individuals provided information or cooperated in survey activities. Appendix A.1 provides a list of individuals responsible for the collection and compilation of data for the “Status of Ducks” section of this report. -

Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge P.O

Yukon Delta Carved by Water Ducks are three times as numerous as geese. Greater scaup, oldsquaw, and pintail are the most abundant species while common scoter, green winged teal, National The most powerful influence of the Yukon Delta terrain mallard, and wigeon are common. Less numerous are is the scouring and building action of water. The Yukon the spectacled and common eiders whose habitat is River carves its way over 2,300 miles to the Bering Sea confined to a narrow coastal zone and the open sea. Wildlife through mountains, foothills, forestland, and tundra. Two hundred miles to the south, the Kuskokwim River also reaches the sea. A centuries-long process, the An estimated 100 million shore and waterbirds Plant Life waters of these two longest rivers in Alaska form a giant representing over 50 species use the Delta for nesting, delta between their mouths. resting, and foraging during migration. These include During the short summer the area bursts into life. There Refuge gulls, jaegars, cranes, loons, grebes, plovers, snipe, are hundreds of species of plants on the refuge, many godwits, sandpipers and the rare bristle-thighed curlew. blooming in splashes of color. Most of the land is The Nulato Hills rise abruptly from the north bank of Dense concentrations of kittiwakes and murres, lesser carpeted by a moist spongy layer of tundra. Permafrost, the Yukon River. The 1.3 million acre Andreafsky numbers of puffins, auklets, guillemots, and cormorants a layer of permanently frozen soil, lies just beneath the Wilderness is located within these hills. The wilderness are found in seabird rookeries along the rocky shores of tundra. -

Sex-Specific Differences in Winter Distribution Patterns of Canvasbacks

Condor, 82:4061116 @ The Cooper Ornithological Society 1980 SEX-SPECIFIC DIFFERENCES IN WINTER DISTRIBUTION PATTERNS OF CANVASBACKS JAMES D. NICHOLS AND G. MICHAEL HARAMIS ABSTRACT.-Winter band recovery distributions of North American Can- vasbacks (Aythya walisineria) suggested that males and females exhibit com- parable degrees of fidelity to general wintering areas. Of birds banded during the winter, the proportion of males was found to be higher in northern than in southern areas. Winter band recovery distributions of birds banded in particular areas during the summer were found to differ significantly between sexes, with females being recovered farther south. Factors that may have affected the evolution of sex-specific wintering distributions include: (1) pos- sible reproductive benefits derived by males who winter in the north and thus reach northerly breeding areas early; (2) sexual dimorphism in body size, which may render the smaller females especially susceptible to periods of inclement weather and food shortages; and (3) interactions between sexes in which males may control food supply when food is scarce. Two lines of evidence from field data on Canvasbacks in the Chesapeake Bay suggest the existence of competition between males and females. First, Canvasbacks trapped during winter in smaller bodies of water tended to have higher pro- portions of females and weigh less than birds trapped in large open bodies of water. Second, analysis of aerial photographs of wintering rafts of Canvas- backs showed patterns of intersexual segregation, with females being found more frequently on peripheral areas of rafts. Lack (1954, 1966) and Fretwell (1972) have ratios of North American waterfowl vary suggested that “limitation” of temperate geographically during the winter. -

American Black Duck Facts

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service American Black Duck Facts Identification Male and female black ducks are similar to female mallards in appearance, but black ducks are darker overall, and have a dark tail. The male has a greenish-yellow bill, and the female’s bill is dark olive. In flight, they have a purple wing-patch on the upper-wing with no white edges. Their silvery-white under-wing linings contrast sharply with these ducks’ dark © Lang Elliot bodies. American Black Duck Life History American black ducks breed in a variety of wetland habitats, from salt marshes to beaver ponds, river islands, and boreal bogs. They winter in salt water along the coasts, but also in a variety of freshwater areas inland, like Cayuga Lake. Black ducks are dabbling ducks, tipping their bodies—head down, tail up— into shallow water to feed. They eat seeds, roots, stems, grain, aquatic © Doug Racine plants and insects, crustaceans, mollusks, and Hen Mallard Duck some small fish. Black duck nests are built on dirt mounds, hidden by vegetation, made of grass and weed stems, and lined with down. After incubation of the eggs, the male black duck does not participate in nesting. Female black ducks lay about 9 eggs, with a range of 7 to 12, and incubates them for 26 to 29 days. Nestlings leave the nest within hours of hatching and remain with their mother until they can fly, at about 60 days. Black Duck X Mallard Hybrid U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service American Black Duck Facts Migration and Wintering Black ducks are most common in the Atlantic and Mississippi flyways, with more numbers along the Atlantic coast. -

Arctic Map.Lay

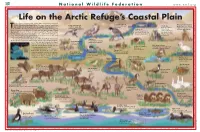

National Wildlife Federation www.nwf.org Longnose Sucker • Brown Bear • Moose • Barren Ground Caribou • Musk-ox • Polar Bear • Wolf • Arctic Fox • Wolverine • Land Otter • Arctic Ground Squirrel • Collared Lemming • Brown Lemming • Tundra Vole • Red-throated Loon • Tundra Swan • Black Brant • Canada Goose • Mallard • American Pintail • Green-winged Teal • American Wigeon • Greater Scaup • Oldsquaw • Common Eider • King Eider • Surf Scoter • Rough-legged Hawk • Golden Eagle • Gyrfalcon • Peregrine Falcon • Merlin • Willow Ptarmigan • Rock Ptarmigan • Semipalmated Plover • Lesser Golden Plover • Black-bellied Plover • Ruddy Turnstone • Snipe • Whimbrel • Pectoral Sandpiper • Least Sandpiper Life on the Arctic Refuge’s Coastal Plain hose in favor of opening the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil drilling often call the region “barren,” and it can Peregrine falcon Arctic ground squirrel Long-tailed jaeger appear that way at first glance. But look again. The plain boasts the Nests on cliffs and Arctic fox Builds dens on low hills, T Feeds on eggs and river bluffs greatest wildlife diversity on Alaska’s northern coast, with denning polar Dens in coastal ridges and pingos where small birds bears, a year-round population of musk-oxen and many dozens of bird Lake trout hills, stream soils are well drained species—including vast numbers of migratory waterfowl. The refuge’s best Lives in larger lakes, banks and pingos known symbol is the 150,000-strong Porcupine caribou herd (named for a in foothills, that do not (mounds created freeze to the bottom by pressure under river), which migrates to the coastal plain every summer to feed, calve and permafrost) seek ocean breezes for relief from mosquitoes. -

Hy – Fly Game Hatcheries

HY – FLY GAME HATCHERIES Breeder Health Programme Presented by Alan Pearson BVM&S DPVM MRCVS. Outline of the Paper • History of the Practice • History of Hy – Fly • The Impetus for recent developments • Vaccination • Other Disease Controls • Conclusions Lanes Vet Group •Formed in 2006 by merging two existing practices •A mixed practice with 16 Vets •A total staff of over 50 people •3 sites •The business sections include •Companion Animal •Farm Animal •Avian •Export •Meat Hygiene •Teaching The Avian Section is run by Mr Pearson & Mr Thompson Who have practiced Poultry medicine for 15 years •Hy – Fly Game Hatcheries •Is the largest Game Hatchery in the UK and probably in Europe •Founded in 1963 by Mr Wilf Holden. •In 1983 Raymond [Wilf’s son] laid the foundations of the modern business • The business has grown every year and last year hatched 4.65 million birds in 18 weeks •35,000 breeding pheasants •18,000 breeding Mallard •13,000 breeding pairs of Partridge •90% of the breeding stock is home reared •The only Commercial breeder of Pure Japanese Green Pheasants in the UK Location Location Location Location Location Location Location The English System Most birds are reared from either Day Old or from 8 weeks by the Gamekeeper Birds are shot on driven shoots with the birds reared on the shoots we do not operate the ‘place to take system’ that you have in the US. Most birds from Hy-Fly leave as either Day–olds or as reared Poults Hy Fly rear up to 100,000 pheasants for replacement and reared bird sales The same system applies to both the Mallard and Partridge The Impetus There have been several factors influencing our programme to improve breeder health and they are as follows:- •Increased production per bird •Increased fertility •To improve our competitiveness •The Salmonella outbreak •To improve chick quality and robustness • A desire to be a groundbreaking business. -

An Evaluation of Captive-Reared Mallard Releases in Virginia

AN EVALUATION OF CAPTIVE-REARED MALLARD RELEASES IN VIRGINIA Prepared by DGIF Mallard Release Committee July 2007 Table of Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY II. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND III. CONCERNS REGARDING CAPTIVE-REARED MALLARD RELEASES A. Diseases Avian Influenza Duck Viral Enteritis Botulism Avian Cholera B. GENETIC DIVERSITY AND HYBRIDIZATION C. CONFOUNDING WATERFOWL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMS Aerial Waterfowl Surveys Waterfowl Breeding Population Surveys Banding Programs Harvest Surveys D. LAW ENFORCEMENT ISSUES E. ADMINISTRATIVE ISSUES F. ECOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL CONCERNS Nuisance issues Impact to waterfowl habitat IV. Illegal Releases V. DEFINITIONS, LAWS AND REGULATIONS PERTAINING TO THE RELEASE OF CAPTIVE- REARED MALLARDS VI. CONCLUSION APPENDIX A GEOGRAPHIC LOCATIONS OF MRA IN VIRGINIA AN EVALUATION OF CAPTIVE-REARED MALLARD RELEASES IN VIRGINIA I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This paper is a review of the practice of releasing captive-reared mallards on shooting preserves in Virginia and will be used by the Department of Game & Inland Fisheries (VDGIF) in evaluating this activity. This review details the potential problems associated with the release of captive-reared mallards. The issues have been well documented and include: disease risks to wild waterfowl and the domestic poultry industry, genetic mixing with wild mallard ducks and hybridization with black ducks, difficulties in surveying and assessing wild duck populations for management and regulatory purposes, ambiguities in wildlife law enforcement concerning live decoys and baiting regulations, and effects on habitats and the ecological community. These factors, along with the costs of controlling disease outbreaks and nuisance duck problems, far outweigh the short-term benefits that mallard release programs offer to a very small percentage of Virginia’s waterfowl hunters.