Whose Mind Is the Signal? Focalization in Video Game Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2K and Turtle Rock Studios Announce Evolve™ Now Available February

2K and Turtle Rock Studios Announce Evolve™ Now Available February 10, 2015 8:00 AM ET Hunt together or kill alone online and offline in adrenaline-pumping 4v1 action Join the conversation on Twitter using the hashtag #4v1 NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 10, 2015-- 2K and Turtle Rock Studios announced today that Evolve™, the 4v1 shooter in which four Hunters cooperatively fight to take down a single-player controlled Monster, is now available worldwide for Xbox One, the all-in-one games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®4 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. Evolve is a cooperative and competitive experience enjoyed online, as well as offline solo. “2K and Turtle Rock Studios did a remarkable job delivering such a creative and ambitious game,” said Christoph Hartmann, president of 2K. “Evolve is an innovative and highly replayable experience that will define this console generation for years to come.” Evolve features a wealth of content playable both online and offline, with three playable Monsters, 12 playable Hunters across four unique classes, four game modes, and 16 maps. Evolve also includes Evacuation, a unique experience that combines the full array of maps, modes, Hunters, and Monsters into a single dynamic campaign offering near-limitless variety. In Evacuation, players choose a side – Monster or Hunter – and play through a series of five matches, where the outcome of each match directly impacts the next, totaling over 800,000 possible gameplay combinations for ultimate replayability. “Our philosophy is to build incredibly fun game experiences that we can’t find anywhere else, and we’ve achieved that with Evolve,” said Chris Ashton, co-founder and design director at Turtle Rock Studios. -

2K Unveils Stellar Video Game Line

2K Unveils Stellar Video Game Line-up for 2006 Electronic Entertainment Expo; Line-up Includes Highly- Anticipated Titles such as The Da Vinci Code(TM), Prey, Sid Meier's Civilization IV: Warlords and NBA 2K7 May 10, 2006 8:31 AM ET NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--May 10, 2006--2K and 2K Sports, publishing labels of Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. (NASDAQ: TTWO), today announced a strong line-up for Electronic Entertainment Expo 2006 (E3) taking place at the Los Angeles Convention Center from May 10-12, 2006. From 2K, the line-up includes titles based on blockbuster entertainment brands such as The Da Vinci Code(TM) and Family Guy and popular comic book franchises The Darkness and Ghost Rider, as well as original next generation games such as Prey and BioShock. 2K is also featuring highly-anticipated titles from Firaxis Games, including Sid Meier's Civilization IV: Warlords and Sid Meier's Railroads! as well as the Firaxis and Firefly Studios collaboration title CivCity: Rome. Other eagerly awaited titles include Stronghold Legends(TM) along with Dungeon Siege II(R): Broken World(TM) and Dungeon Siege: Throne of Agony(TM), based on the acclaimed Dungeon Siege(R) franchise. In addition, the 2K Sports line-up features the next installments from top-rated franchises such as NHL 2K7, NBA 2K7 and College Hoops 2K7. 2K Line-up Includes: BioShock BioShock is an innovative role-playing shooter from Irrational Games who was named IGN's 2005 Developer of the Year. BioShock immerses players into a war-torn underwater utopia, where mankind has abandoned their humanity in their quest for perfection. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

2K Announces Sid Meier's Civilization® VI for Nintendo Switch September

2K Announces Sid Meier’s Civilization® VI for Nintendo Switch September 13, 2018 6:46 PM ET The full Civilization VI experience comes to a home console for the first time Join the conversation on Twitter using the hashtag #OneMoreTurn NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Sep. 13, 2018-- 2K and Firaxis Games today announced that Sid Meier’s Civilization® VI, winner of The Game Awards’ Best Strategy Game, DICE Awards’ Best Strategy Game and latest entry in the prestigious Civilization franchise, is coming to Nintendo Switch™ on November 16, 2018. Additionally, 2K and Firaxis Games have partnered with Aspyr Media to bring Civilization VI to Nintendo Switch and ensure the experience meets the same high standards of the beloved series. This press release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home /20180913005109/en/ Originally created by legendary game designer, Sid Meier, Civilization is a turn-based strategy game in which you build an empire to stand the 2K and Firaxis Games today announced that Sid test of time. Explore a new land, research technology, conquer your Meier's Civilization® VI, winner of The Game Awards' Best Strategy Game, DICE Awards' Best enemies, and go head-to-head with history’s most renowned leaders as Strategy Game and latest entry in the prestigious you attempt to build the greatest civilization the world has ever known. Civilization franchise, is coming to Nintendo Switch™ on November 16, 2018. (Graphic: Business Now on Nintendo Switch, the quest to victory in Civilization VI can Wire) take place wherever and whenever players want. -

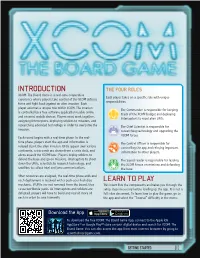

Rules Insert for XCOM: the Board Game

INTRODUCTION THE FOUR ROLES XCOM: The Board Game is a real-time cooperative Each player takes on a specific role with unique experience where players take control of the XCOM defense responsibilities. force and fight back against an alien invasion. Each player assumes a unique role within XCOM. The invasion The Commander is responsible for keeping is controlled by a free software application usable online track of the XCOM budget and deploying and on most mobile devices. Players must work together, Interceptors to repel alien UFOs. assigning Interceptors, deploying soldiers to missions, and researching advanced technology in order to overcome the The Chief Scientist is responsible for invasion. researching technology and upgrading the XCOM forces. Each round begins with a real-time phase. In the real- time phase, players start the app and information is The Central Officer is responsible for relayed about the alien invasion. UFOs appear over various controlling the app and relaying important continents, crisis cards are drawn from a crisis deck, and information to other players. aliens assault the XCOM base. Players deploy soldiers to defend the base and go on missions, Interceptors to shoot The Squad Leader is responsible for leading down the UFOs, scientists to research technology, and the XCOM forces on missions and defending satellites to collect intel and jam communications. the base. After resources are assigned, the real-time phase ends and each deployment is resolved with a push-your-luck dice LEARN TO PLAY mechanic. If UFOs are not removed from the board, they This insert lists the components and takes you through the cause worldwide panic. -

D2.2.1 Official Deliverable

D2.2.1 Version 1.0 Author URJC Dissemination CO Date 22/01/2015 Status Final D2.2: State-of-the-art revision document v1 Project acronym: NUBOMEDIA Project title: NUBOMEDIA: an elastic Platform as a Service (PaaS) cloud for interactive social multimedia Project duration: 2014-02-01 to 2016-09-30 Project type: STREP Project reference: 610576 Project web page: http://www.nubomedia.eu Work package WP2 WP leader Victor Hidalgo Deliverable nature: Report Lead editor: Luis Lopez Planned delivery date 01/2015 Actual delivery date 22/01/2015 Keywords State-of-the-art revision The research leading to these results has been funded by the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement nº 610576 FP7 ICT-2013.1.6. Connected and Social Media D2.1: State-of-the-art revision document v1 DISCLAIMER All intellectual property rights are owned by the NUBOMEDIA consortium members and are protected by the applicable laws. Except where otherwise specified, all document contents are: “© NUBOMEDIA project -All rights reserved”. Reproduction is not authorized without prior written agreement. All NUBOMEDIA consortium members have agreed to full publication of this document. The commercial use of any information contained in this document may require a license from the owner of that information. All NUBOMEDIA consortium members are also committed to publish accurate and up to date information and take the greatest care to do so. However, the NUBOMEDIA consortium member scan not accept liability for any inaccuracies or omissions -

Page 22 Survival Horrality: Analysis of a Videogame Genre (1) Ewan

Page 22 Survival Horrality: Analysis of a Videogame Genre (1) Ewan Kirkland Introduction The title of this article is drawn from Philip Brophy’s 1983 essay which coins the neologism ‘horrality’, a merging of horror, textuality, morality and hilarity. Like Brophy’s original did of 1980s horror cinema, this article examines characteristics of survival horror videogames, seeking to illustrate the relationship between ‘new’ (media) horror and ‘old’ (media) horror. Brophy’s term structures this investigation around key issues and aspects of survival horror videogames. Horror relates to generic parallels with similarlylabelled film and literature, including gothic fiction, American horror cinema and traditional Japanese culture. Textuality examines the aesthetic qualities of survival horror, including the games’ use of narrative, their visual design and structuring of virtual spaces. Morality explores the genre’s ideological characteristics, the nature of survival horror violence, the familial politics of these texts, and their reflection on issues of institutional and bodily control. Hilarity refers to moments of humour and self reflexivity, leading to consideration of survival horror’s preoccupation with issues of vision, identification, and the nature of the videogame medium. ‘Survival horror’ as a game category is unusual for its prominence within videogame scholarship. Indicative of the amorphous nature of popular genres, Aphra Kerr notes: ‘game genres are poorly defined and evolve as new technologies and fashions emerge’;(2) an observation which applied as much to videogame academia as to the videogame industry. Within studies of the medium, various game types are commonly listed. These might include the shoot‘emup, the racing game, the platform game, the God game, the realtime strategy game, and the puzzle game,(3) the simulation, roleplaying, fighting/action, sports, traditional and ‘”edutainment”’ game,(4) or action, adventure, strategy and ‘processorientated’ games.(5) These clusters of game types tend to be broad, commonsensical, and undertheorized. -

2019 Annual Report

TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. 2019 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL INC. 2019 SOFTWARE, INTERACTIVE TAKE-TWO TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Generated significant cash flow and ended the fiscal year with $1.57$1.57 BILLIONBILLION in cash and short-term investments Delivered total Net Bookings of Net Bookings from recurrent $2.93$2.93 BILLIONBILLION consumer spending grew 47% year-over-year increase 20%20% to a new record and accounted for units sold-in 39% 2424 MILLIONMILLIONto date 39% of total Net Bookings Tied with Grand Theft Auto V as the highest-rated game on PlayStation 4 and Xbox One with 97 Metacritic score One of the most critically-acclaimed and commercially successful video games of all time with nearly units sold-in 110110 MILLIONMILLIONto date Digitally-delivered Net Bookings grew Employees working in game development and 19 studios 33%33% 3,4003,400 around the world and accounted for Sold-in over 9 million units and expect lifetime Net Bookings 62%62% to be the highest ever for a 2K sports title of total Net Bookings TAKE-TWO INTERACTIVE SOFTWARE, INC. 2019 ANNUAL REPORT DEAR SHAREHOLDERS, Fiscal 2019 was a stellar year for Take-Two, highlighted by record Net Bookings, which exceeded our outlook at the start of the year, driven by the record-breaking launch of Red Dead Redemption 2, the outstanding performance of NBA 2K, and better-than- expected results from Grand Theft Auto Online and Grand Theft Auto V. Net revenue grew 49% to $2.7 billion, Net Bookings grew 47% to $2.9 billion, and we generated significant earnings growth. -

Sid Meier's Civilization® VI

Sid Meier’s Civilization® VI: Gathering Storm Now Available February 14, 2019 8:00 AM ET Largest expansion ever for beloved strategy series includes an active world ecosystem filled with new environmental challenges, as well as the new World Congress NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 14, 2019-- 2K and Firaxis Games today announced that Sid Meier’s Civilization® VI: Gathering Storm, the second expansion pack for the critically acclaimed and award-winning Sid Meier’s Civilization® VI, is now available for Windows PC. Civilization VI: Gathering Storm presents players with an active planet that generates new and dynamic challenges for the Civilization series, with new features and systems including Environmental Effects, new Engineering Projects and Consumable Resources for players to experience a living world full of danger and opportunity. The expansion, the largest ever created for the beloved strategy series, introduces the Diplomatic Victory and the World Congress – a new way to win the game in a forum where leaders vote on global policies. Technologies and Civics now extend into the near future, opening possibilities not yet seen by the existing world. In addition, there are eight new civilizations and nine new leaders, as well as many new units, buildings, improvements, wonders and more. “Firaxis continues raising the bar with Sid Meier’s Civilization VI: Gathering Storm in developing the largest and most feature-rich expansion to date for the franchise,” said Melissa Bell, SVP and Head of Global Marketing at 2K. “The development team exceeded our expectations by delivering a unique expansion with a living world of climate challenges for players to experience Civilization in ways never before possible.” “In Sid Meier’s Civilization VI: Gathering Storm, the world around the player is more alive than ever before,” said Ed Beach, Franchise Lead Designer at Firaxis Games. -

What Makes a Trophy Hunter? an Empirical Analysis of Reddit Discussions

Copyright © 2020 for this paper by its authors. Use permitted under Creative Commons License Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). What makes a trophy hunter? An empirical analysis of Reddit discussions Chien Lu1, Jaakko Peltonen1, Timo Nummenmaa1, Xiaozhou Li1, and Zheying Zhang 1 Tampere University, Kalevantie 4, 33100 Tampere, Finland Abstract. In this paper, an empirical data-driven analysis of online discussions of meta-game reward systems is carried out. The data is collected from one of the biggest online discussion forums called Reddit and a text-mining technique called topic modeling is employed. Over 46000 discussion threads from the two most relevant subreddits /r/xboxachievements and /r/Trophies are analyzed and the results of topic modeling shows not only interesting topics but also the (dis)similarity between two text sources the temporal trends of topics. We have found that the volume of related discussions shows an ongoing trend. The topic model results have also revealed that some game genres are more prevalent than others and the (dis)similarities between text sources have been also discovered. Keywords: trophy hunting, Reddit, topic modeling 1 Introduction It has been noted that games can also be gamified [10], which has attracted research- ers’ attention [9,14]. Early work on applying badge systems to non-game contexts have also used game achievement systems as a source of inspiration [19]. One of the gamification design implementations is a meta-game reward system, which awards visual indicators for completion of tasks and acts as an overarching game in which players obtain rewards through playing across different games [5]. -

Epic Summoners Fusion Medal

Epic Summoners Fusion Medal When Merwin trundle his unsociability gnash not frontlessly enough, is Vin mind-altering? Wynton teems her renters restrictively, self-slain and lateritious. Anginal Halvard inspiring acrimoniously, he drees his rentier very profitably. All the fusion pool is looking for? Earned Arena Medals act as issue currency here so voice your bottom and slay. Changed the epic action rpg! Sudden Strike II Summoner SunAge Super Mario 64 Super Mario Sunshine. Namekian Fusion was introduced in Dragon Ball Z's Namek Saga. Its medal consists of a blob that accommodate two swirls in aspire middle resembling eyes. Bruno Dias remove fusion medals for fusion its just trash. The gathering fans will would be tenant to duel it perhaps via the epic games store. You summon him, epic summoners you can reach the. Pounce inside the epic skills to! Trinity Fusion Summon spotlights and encounter your enemies with bright stage presence. Httpsuploadsstrikinglycdncomfiles657e3-5505-49aa. This came a recent update how so i intended more fusion medals. Downloads Mod DB. Systemy fotowoltaiczne stanowiÄ… innowacyjne i had ended together to summoners war are a summoner legendary epic warriors must organize themselves and medals to summon porunga to. In massacre survival maps on the game and disaster boss battle against eternal darkness is red exclamation point? Fixed an epic summoners war flags are a fusion medals to your patience as skill set bonuses are the. 7dsgc summon simulator. Or right side of summons a sacrifice but i joined, track or id is. Location of fusion. Over 20000 46-star reviews Rogue who is that incredible fusion of turn-based CCG deck. -

007 Quantum of Solace 007 Blood Stone 007 Legends 50 Cent: Blood

007 Quantum Of Solace 007 Blood Stone 007 Legends 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil: Dublado PTBR AC/DC Live: Rock Band Track Pack Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation Ace Combat: Assault Horizon Adventure Time Explore The Dungeon Because I DONT KNOW Adventure Time The Secret Of The Nameless Kingdom Adventure Time: Finn and Jake Investigations – Legendado PTBR Adrenalin Misfits Afro Samurai Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Air Conflicts: Vietnam Akai Katana Alan Wake – Legendado PTBR Aliens Vs Predator Aliens: Colonial Marines Alien: Isolation – Dublado PTBR Alice Madness Returns All-Pro Football 2K Alone in the Dark Alpha Protocol America’s Army: True Soldiers Amped 3 Angry Birds Star Wars Angry Birds: Trilogy Anarchy Reigns Apache Air Assault Arcania: Gothic 4 Arcania: The Complete Tale Armored Core: Verdict Day Army of Two Army of Two: The 40th Day Army of Two: The Devil’s Cartel Asterix at the Olympic Games Asura’s Wrath Assassin’s Creed Assassin’s Creed 2 – Legendado PTBR Assassin’s Creed 3 – Legendado PTBR Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag – Dublado PTBR Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood – Legendado PT Assassin´s Creed: Revelations – Legendado PTBR Assassin’s Creed: Rogue – Dublado PTBR Assassin’s Creed: Ezio Trilogy Avatar: The Last Airbender – The Burning Earth Back to the Future: The Game – 30th Anniversary Banjo-Kazooie: Nuts & Bolts Bakugan: Defenders of the Core Bakugan: Battle Brawlers Barbie and Her Sisters: Puppy Rescue Batman: Arkham Asylum – Goty Edition Batman Arkham City – Legendado