UBCMJ Volume 10 Issue 2 | Spring 2019 Contents VOLUME 10 ISSUE 2 | Spring 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

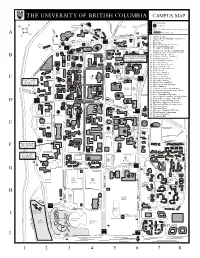

University of British Columbia Campus Map

THEUNIVERSITYOFBRITISHCOLUMBIA CAMPUSMAP L VisitorParking: 7 e P Parkades g e P TicketDispenserorMeterParkingLots n GREEN Pedestrianzone A COLLEGE d MUSEUMOF ANTHROPOLOGY 1.AquaticCentre 25 2.Angus(Henry)Building(Commerce) 3.AsianCentre P GATE Duke 3 Hall 4.Bookstore Norman 28 ROSE P GARDEN 5.BrockHall(StudentServices) Mackenzie GATE PARKADE Carr 6.BuchananBuilding(Arts) Hall House 4 8 7.CecilGreenParkHouse 36 ROSE GARDEN Carey 8.ChanCentreforthePerformingArts 17 Hall 34 9.ChoiBldg(Inst.ofAsianResearch) 20 22 10.CICSR/ComputerScience D B Belkin WALTERGAGERESIDENCE 11.ComputerScienceBuilding 15 Art P St.Andrews &CONFERENCECENTRE 12 .ContinuingStudies Gallery C E Housing 9 5959StudentUnionBlvd. 13.FirstNationsLonghouse A 14 .ForestryBuilding Nitobe 6 3 Buchanan 15 .FredericWoodTheatre P 26 21 B Memorial Tower 16.GeographyBuilding Garden NORTH P 5 PARKADE 17.GraduateStudentCentre FRASER P 18.HebbTheatre RIVER 19.HenningsBuilding PARKADE 20 .InternationalHouse KOERNER MAIN 21 .LasserreBuilding C 24 LIBRARY LIBRARY GATE 22.Law(Curtis)Building 13 16 2 PLACEVANIER 32 23.MacMillanBuilding RESDENCE 24.MathematicsBuilding 1935LowerMall 33 25.MuseumofAuthropology STUDENT 26.MusicBui lding 11 UNION MacInnes 27.OsborneCentre(Gymnasium) 19 BUILDING Field P TREKKERS 28.Parking&CampusSecurityOffices RESTAURANT 29.PonderosaBuilding 18 Chemistry 30.ScarfeBuilding(Education) 29 2 1 31.SocialWork,Schoolof(JackBellBldg) 31 32.StudentRecreationCentre(SRC) GATE BUS LOOP 33.StudentUnionBuilding(SUB) D 6 P 39 34.Theology,VancouverSchoolof 35.ThunderbirdWinterSportsCentre St.John’s 4 College 36. UniversityCentre 12 30 40 37.UniversityVillage GATE 38.VancouverHospital(UBCSite) P 1 39.WarMemorialGymnasium WEST 40.WesbrookBuilding PARKADE 41.Woodward/IRC 41 E REGENT COLLEGE University 37 Village CEMELabs P P HEALTH Barn SCIENCES 38 Coffee PARKADE Shop GATE 7 RITSUMEIKAN- 23 F UBCHOUSE 6450AgronomyRd. -

Curriculum Vitae Derryck H Smith, M.D

Curriculum Vitae Derryck H Smith, M.D. F.R.C.P. (C) EDUCATION 1. University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario B.Sc. Chemistry 1970 2. University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario Medical Doctor 1974 3. Internship: Ottawa General Hospital 1974 – 1975 4. Psychiatry Residency: University of British Columbia Completed 1984 5. Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians & Surgeons of Canada Psychiatry 1985 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENT Clinical Professor Emeritus, Department of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia CURRENT POSITIONS 1. Private Practice 2. Member, Division of Child and Adolescent and Forensic Psychiatry, UBC 3. Honorary Staff, BC Children’s Hospital 4. Consultant to Oak Group, Boston, Massachusetts USA AREAS OF PRACTICE AND EXPERTISE 1. Civil litigation, personal injury claims 2. Traumatic Brain Injury - children, teens & adults 3. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder – children, teens & adults 4. Disability assessments - including adjudication of disputed claims PEER REVIEW FOR ACADEMIC JOURNALS 1. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2. Brain Injury 3. International Journal of Obesity 4. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 5. Advisory Board, International Brain Research Foundation 6. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 7. Pharmaceutical Medicine 8. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 9. Journal of the American Medical Association TEACHING & SCHOLARLY PRESENTATIONS Lectures (Abbreviated List since 2000) 1. The Advantages of a Medical Care System with Multiple Sources of Funding. Presented at Eldercollege at Capilano College, April 27th 2000 2. Lecture: Efficient Interventions to Alter Behaviour in Children, 8th Annual Paediatric and Adolescent Refresher for General Practitioners, Sheraton Wall Centre Hotel, Vancouver BC, May 5th 2000 Updated: April 2017 Page 1 of 19 Curriculum Vitae Derryck H. -

Department of Medicine 2009 Annual Report

Department of Medicine 2009 Annual Report The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM DR. GRAYDON MENEILLY 2 Heads & Directors 4 Administration 5 Research 7 Committee for Appointments, Reappointments, Promotion and Tenure 8 Teaching Effectiveness Committee 10 DIVISION REPORTS AIDS 11 Allergy & Immunology 20 Cardiology 23 Community Internal Medicine 36 University of British Columbia Critical Care Medicine 39 Department of Medicine 2009 Annual Report Endocrinology 44 Gastroenterology 47 Graydon S. Meneilly General Internal Medicine 53 Professor and Eric W. Hamber Chair Geriatric Medicine 60 Head, Department of Medicine, Hematology 64 Vancouver Hospital Infectious Diseases 67 Contributors Medical Oncology 69 Division Heads and Administrators Program Directors and Managers Nephrology 71 Neurology 77 Linda Rasmussen Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation 85 Director of Administration Department of Medicine Respiratory Medicine 88 Rheumatology 91 Editor Donna Combs Members at Large 97 Department of Medicine EDUCATIONAL PROGRAMS Designer Clinical Investigator Program 98 Sabina Fitzsimmons Department of Medicine Continuing Medical Education Program 103 Graduate Studies Program in Experimental Medicine 104 Cover photo Courtesy of “Tourism Vancouver” Postgraduate Education Program 109 International Health Project 111 Photography Undergraduate Education Program 113 Janis Franklin Andy Fang Photospin Departmental Strategic Directions 2009 114 Canada Research Chairs & Endowed Chairs 121 Printer RR Donnelly Research Funding 128 Publications 129 Affiliated Institutes 130 Mentoring Program 131 Honours and Awards 132 DEPARTMENT HEAD’S MESSAGE t is my pleasure to introduce the annual report of the UBC IDepartment of Medicine. 2009 was a busy and successful year despite economic challenges, and our success is a reflection of the tremendous talent and dedication of our faculty, staff, residents and students. -

4172 UBC Medicine Issue 7 Spring 2012 Optlinks V2revised.Indd

12 Southern Medical 15 An artifi cial 29 John Webb: Heart Program opens epidemic of valve replacement its doors ADHD pioneer UBC MEDICINE VOL 8 | NO 1 SPRING 2012 THE MAGAZINE OF THE UBC FACULTY OF MEDICINE Personality Transference Recovery PORT MOODY Serotonin BURNABY Gender COQUITLAM roles PITT MEADOWS Catharsis Culture shock PORT Care COQUITLAM Coping mechanisms NEW Identity WESTMINSTER Fraser River MAPLE RIDGE Fraser River Self-image EXTENDING MENTAL HEALTH TO THE SUBURBS Projection NEW RESIDENCY LURES ASPIRING AND SEASONED PSYCHIATRISTS TO FRASERAbuse HEALTH Sublimation LANGLEY Alienation Medication Psychoanalysis SURREY Crisis Cognitive DELTA Counselling behavioural Deinstitutionalization therapy Inclusion 12 14 10 FACULTY OF MEDICINE 06 UBC MEDICINE VOL. 8 | NO. 1 SPRING 2012 A publication of the University of British Columbia’s Faculty of Medicine, providing news and information for and about Message from the Vice Provost Health and Dean 03 faculty members, students, staff, alumni and friends. Focus on: The Fraser Health region Letters and suggestions are welcome. Contact Brian Kladko Extending psychiatric training – and care – to Fraser Health 04 at [email protected] A “Surrey boy” comes home 06 Editor/Writer Brian Kladko Royal Columbian: A history of clinical education 06 Contributing writers A new model for medical education – by way of Chilliwack 07 Libby Brown Anne McCulloch The Faculty of Medicine’s Fraser footprint 08 Ian McLeod Additional Research Research thriving in Fraser region 10 Melissa Carr Distribution coordinator -

The Word Winter 2017 Draft

issue 4 - winter 2017 the WORD a newsletter for alumni and friends of the UBC English Department FROM GAME OF THRONES TO RARE MANUSCRIPTS: WHAT’S NEW IN ENGLISH Snapshots of some of the compelling new projects and initiatives in the department page 4 TWO PHD STUDENTS WIN VANIER AWARDS Szu Shen and Sheila Giffen win the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council’s top prize for PhD students page 14 CANLIT GUIDES WORKSHOP Kathryn Grafton and Laura Moss lead a new era of CanLit Guides for classroom use page 28 THE MARY QUAN LEE LEGACY Learn more about alumna Mary Quan Lee and her ongoing legacy in the English department page 38 CONTENTS 3 ALUMNI TESTIMONIAL - ALIX HAWLEY 4 SNAPSHOTS: WHAT’S NEW IN ENGLISH 5 MESSAGE FROM THE HEAD The Word is published by 6-10 FACULTY NEWS The Department of English, • new hires The University of British Columbia • honours and accomplishments www.english.ubc.ca • faculty bookshelf EDITOR & DESIGNER Dr. Lucia Lorenzi 11 POSTDOCTORAL NEWS [email protected] 12 ALUMNI TESTIMONIAL - STEPHANIE IP EDITORIAL CONSULTANT Dr. Mary Chapman [email protected] 13-19 GRADUATE NEWS • message from the graduate head: Dr. Sandra Tomc CONTRIBUTING WRITERS • Szu Shen and Sheila Giffen: vanier winners Dr. Leslie Arnovick • 2015/2016 graduates Tanya Bennett • graduate presentations & publications Dr. Siân Echard Stephen Ney: PhD graduate teaching abroad Eleanor Hoskins • Dr. Lucia Lorenzi • the prose: english graduate softball team takes 6th place Dr. Laura Moss Dr. Stephen Ney 20-23 UNDERGRADUATE NEWS Dr. Vin Nardizzi • message from the undergraduate head: Dr. -

UBC Faculty of Medicine Guidelines for Resumption of On-Site (In- Person) Education Activities in Academic Learning Spaces

UBC Faculty of Medicine Guidelines for Resumption of On-site (In- Person) Education Activities in Academic Learning Spaces Updated: July 07, 2020 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 UBC Faculty of Medicine Guiding Principles ........................................................................................ 3 3.0 Sharing of Responsibilities ................................................................................................................. 4 4.0 Reference Documents........................................................................................................................ 4 5.0 General Prevention of Exposure to COVID-19 ..................................................................................... 5 5.1 Physical Distancing ....................................................................................................................................... 5 5.2 Assess your Health Before Accessing an Academic Learning Space ............................................................ 5 5.3 Hand Hygiene ............................................................................................................................................... 6 5.4 Training ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 6.0 General Building and Learning Space Considerations -

Faculty of Medicine Is One of the Top Ranked in Canada

CAREER OPPORTUNITY Physician, Obstetrics & Gynaecology and Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility (REI) Reproductive Surgeon The UBC Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, in collaboration with Vancouver General Hospital (VGH) and University of British Columbia Hospital (UBCH), BC Women’s Hospital (BCWH) is seeking a Reproductive Endocrinologist/Suregon with expertise in Reproductive Surgery, for a Part-Time position. This opportunity is for internal candidates only. While providing excellence in Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility in their current practiice , there is an expectation of a commitment to Reproductive Surgery clinical care and research. Your practice will involve applying current research evidence and best practice standard, to deliver the highest quality of surgical care and inform provincial policies in the area of Reproductive Surgery. Your surgical time is decided upon by the surgical committee based on the current institutional stndards. You are also expected to cover Gynecology call at Vancouver General Hospital according to the current regulations. Clinical care will be provided at VGH, BCWH, UBCH or the ambulatory surgical care center (ASC). Given the dual appointment at the division and Vancouver Coastal Health system (VCH), you will report to the Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at VCH and to the division head of REI for all clinical responsibilities, administrative and HR related matters. For academic issues, you will report to the UBC Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. The position will be based within the UBC Division of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and/or the Division of Gynaecologic Reproductive Endocrinology to best resource the candidate for academic success. You will participate in educational programs of the UBC Department for undergraduate medical student teaching, post-graduate resident teaching and subspecialty fellowship teaching. -

Analysis Director Appointed Dr

Volunac 29, Number 2 January 19,1983 Analysis director appointed Dr. John S. Chase will join the University of B.C. on April 1 as director of the campus Office of Institutional Analysis. Dr. Chase is currently executive assistant to the president and director of the Office of Analytical Studies at Simon Fraser University. Dr. Chase, 45, succeeds Dr. William Tetlow, who resigned as director of the UBC office in June, 1982, to accept a position with the U.S. National Centre for Higher Education Management Systems in Boulder, Colorado. As director of the UBC office, Dr. Chase will report to Prof. Michael Shaw, UBC’s vice-president academic and provost. UBC‘s Office of Institutional Analysis provides data, information, reports and analyses to the President’s Office, the Board of Governors, Senate and other officers of the University or committees charged with developing or implementing policy on such matters as budget, enrolment, space and faculty. Dr. Chase is a graduate of the University of Michigan, where he was awarded the degrees of Bachelor of Business I Administration in accounting in 1960, Master of Arts in economics and higher education administration in 1968, and Doctor of Philosophy in higher education and administration in 1969. Prior to joining SFU in 1969, Dr. Chase Plea=- turn to page 2 See ANALYSIS Chemistty department head Larry Weiler confers with research associate Margot Alerdice. Prof. Larry Weiler, who became head is very demanding. .at least four or five year for the 88 courses we offer. Many of of UBC’s Department of Chemistry last hours is spent making ready for one hour those students, of course, are enrolled in year, inaugurates a new UBC Reports in the classroom. -

David Harriman, MD, FRCSC

David Harriman, MD, FRCSC M.D. University of British Columbia Urology Residency, University of British Columbia Abdominal Organ Transplant Fellowship, Wake Forest School of Medicine David Harriman is a fellowship trained Abdominal Organ Transplant joined UBC Faculty of Medicine as an Assistant Professor in the Department of Urologic Sciences, effective July 1, 2019. Dr. Harriman has spent 2 years in North Carolina at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, an accredited American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS) Kidney and Pancreas Fellowship, working with pioneers and innovators in the field of transplantation; Dr. Robert Stratta, Dr. Jeffrey Rogers, Dr. Alan Farney, Dr. Giuseppe Orlando and Dr. Colleen Jay. The abdominal organ transplant program at Wake Forest is fully integrated, with transplant surgeons involved in research, immunosuppression, and rejection management in close collaboration with transplant nephrology. Prior to his subspecialty training, Dr. Harriman completed his MD degree (2012) and Urology residency (2017) at the University of British Columbia. Dr. Harriman joined the Vancouver General Hospital renal transplant group, consisting of transplant surgeons (Dr. Christopher Nguan and Dr. Mark Nigro), as well as transplant nephrologists (Dr. Olwyn Johnston, Dr. James Lan and Dr. Matthew Kadatz). He will provide pre‐transplant, surgical care and post‐transplant management of this complex patient population within a multidisciplinary, team environment. He plans to remain active in all aspect of kidney and pancreas transplantation with special interests in transplantation of kidneys from marginal donors and transplantation of medically and surgically high risk recipients. Dr. Harriman will be an active member of all clinical transplant research initiatives involving the VGH renal transplant group, and will be involved in medical education, specifically surgical mentorship and developing systems to enable trainees to learn and perform to their highest level. -

4107.Med Mag Art Apr25 4/25/07 12:16 PM Page C1 UBC MEDICINE the MAGAZINE of the UBC FACULTY of MEDICINE Volume 3 Number 2 Spring/Summer 2007

4107.Med Mag_art_Apr25 4/25/07 12:16 PM Page c1 UBC MEDICINE THE MAGAZINE OF THE UBC FACULTY OF MEDICINE Volume 3 Number 2 Spring/Summer 2007 Who Are These People AND WHAT ARE THEY DOING AT ART COLLEGE? Telling Tales THE DOCTOR IS IN . THE STORYTELLING BUSINESS 13 From the Dalai Lama to the Opera THE INNOVATIVE INSTITUTE OF MENTAL HEALTH 16 Medical Alumni News 21 4107.Med Mag_art_Apr25 4/25/07 12:16 PM Page c2 T HE D REAM H EALER— An Operatic Partnership of Art and Medicine 18 On stage at the Chan Centre, foreground (L) Music’s Nancy Hermiston with Psychiatry’s Athanasios Zis; (R) Allan Young, Institute of Mental Health, with librettist Don Mowatt and composer Lloyd Burritt. 4107.Med Mag_art_Apr25 4/25/07 12:16 PM Page 1 6 In This Issue UBC MEDICINE MAGAZINE DEPARTMENTS is published twice a year by the Faculty of Medicine at the University of British Columbia. It provides news 2 Letters and information for and about faculty members, students, staff, alumni and friends. 3 The Dean’s Page: The Art of Medicine 4 Submissions and suggestions are welcome. 6 Flash: News from . Contact [email protected]. Letters are published at the editor’s discretion 12 Point of View: What Is It about the Arts? and may be edited for length. Volume 3 Number 2 Spring/Summer 2007 PROFILES Editor-in-Chief (Acting) 4 What Are You Doing After Work? Dr. Dorothy Shaw, Senior Associate Dean, Faculty Affairs A physiotherapist and a cardiologist take a left turn into art and art college—or is it the right turn? Editor/Managing Editor 10 Miro Kinch Editorial Advisory Committee 10 Remembering Dr. -

Annual Report 2015 | 2016 TABLE of CONTENTS OVERVIEW of the DEPARTMENT of MEDICINE Heads and Directors

UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE Annual Report 2015 | 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW OF THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE Heads and Directors.................................................................... 2 Committees................................................................................... 3 Administration.............................................................................. 11 RESEARCH Activities....................................................................................... 12 Research Metrics and Highlights............................................ 12 EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Accomplishments and Highlights........................................... 13 DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE Undergraduate Medical Education Program (UGME)....... 13 Annual Report 2015 | 2016 Postgraduate Medical Education Program (PGME)........... 13 Experimental Medicine.............................................................. 16 Dr. Graydon S. Meneilly, MD, FRCPC, MACP DIVISION REPORTS Professor and Eric W. Hamber Chair AIDS................................................................................................ 17 Head, UBC Department of Medicine Allergy and Immunology.......................................................... 20 Physician-in-Chief & Head, Cardiology.................................................................................... 22 Community Internal Medicine................................................ 25 Department of Medicine Critical Care Medicine.............................................................. -

Weihong Song, MD, Phd (宋伟宏)

T H E U N I V E R S I T Y O F B R I T I S H C O L U M B I A Weihong Song, MD, PhD (宋伟宏) Fellow of the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences Jack Brown and Family Professor and Canada Research Chair in Alzheimer’s Disease Senior Advisor to UBC President on China Associate Director, Institute of Mental Health Director, Basic Neuroscience Division, Department of Psychiatry Director, UBC Townsend Family Laboratories Department of Psychiatry, The University of British Columbia 2255 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z3, Canada Tel: 604-822-8019, Fax: 604-822-7756, Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.neuroscience.ubc.ca/song.htm Professional Experience 2017- Senior Advisor to the President on China 2015- Associate Director, Institute of Mental Health 2015- Director, Basic Neuroscience Division, Department of Psychiatry 2012- Canada Research Chair in Alzheimer’s Disease (Tier 1) 2010- Professor (with tenure) 2009-2016 Special Advisor to the President on China 2008- Director, UBC Townsend Family Laboratories 2001- Jack Brown and Family Professorship & Chair in Alzheimer's Disease 2002-2012 Canada Research Chair in Alzheimer’s Disease (Tier 2) 2006-2010 Associate Professor (with tenure), 2004-2008 Postdoctoral Coordinator for Faculty of Medicine 2001-2006 Assistant Professor (tenure track) Department of Psychiatry/Brain Research Center The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada 1999-2001 Instructor 1996-1999 Postdoctoral Research Fellow (Supervisor: Bruce A. Yankner, MD, PhD) Department of Neurology Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA 1988-1990 Chief Psychiatrist and Lecturer of Psychiatry 1986-1988 Chief Resident Doctor and Assistant Professor of Psychiatry 1983-1986 Psychiatry Residency Department of Psychiatry and Institute of Mental Health The First Affiliated Hospital West China University of Medical Sciences, Chengdu, China Education 1993-1996 Ph.D., Program of Medical Neurobiology (Supervisor: Debomoy K.