University of Birmingham a Re-Evaluation of Colonel Benjamin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fort Concho Historical Trail

FORT CONCHO HISTORICAL TRAIL Brought to you by Concho Valley Council Boy Scouts of America FORT CONCHO HISTORICAL TRAIL Fort Concho was established on December 4, 1867, after the army had to abandon Fort Chadbourne (located north of what is now Bronte, Texas) for lack of good water. The new fort was located at the junction of the North and South Concho Rivers. The fort consisted of some forty buildings and was constructed of native limestone. Fort Concho was closed in June 1889 after having served this area for some twenty-two years. Today, the fort is a National Historical Landmark. The Fort Concho Historical Trail takes you not only through this Fort, but also along some of the streets of the settlement of Santa Angela, now San Angelo that was developed to serve the needs of the men who were stationed at the Fort. In 1870, a trader and promoter named Bart DeWitt bought 320 acres of land for $1.00 an acre, marked off town lots and offered them for sale. The town of Santa Angela grew from just a few people to the thriving city it is today. On the trail you will take downtown, you will see some of the old buildings of this early community as well as some of the other historical areas along the Concho River. The Concho River was named from the mussel shells found in the river. THOSE ELIGIBLE TO HIKE THE TRAIL All members of the Boy Scouts of America, the Girl Scouts USA and all adults, parents and Scouters who go with them, are eligible to hike the trail and earn the Fort Concho Historical Trail Patch if they follow the trail requirements as listed. -

D. G. & D. A. Sanford

University of Oklahoma College of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 4-5-1878 D. G. & D. A. Sanford. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/indianserialset Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation H.R. Rep. No. 465, 45th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1878) This House Report is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian and Alaskan Native Documents in the Congressional Serial Set: 1817-1899 by an authorized administrator of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 45TH CONGREss, } HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. REPORT 2d Session. { No. 465. D. G. & D. A. SANFORD. APRIL 5, 1878.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole Honse and ordered to be printed. Mr. MORGAN, from the Committee on Indian Affairs, submitted the fol lowing REPORT: [To accompany bill H. R. 4241.] The Committee on Indian Affairs, to whom was referred the petition for the relief of D. G. & D. A. Sanford, report: That Messrs. D. G. & D. A. Sanford have been engaged for years as cattle-drivers, and on or about the 12th day of June, 1872, they started from ~he county of San Saba, in Texas, with 2, 782 head of cattle for California. They also had with them 38 horses and mules, 4 yoke of oxen, and 2 wagons, which contained their provisions and outfit. -

'The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid Into Alabama'

H-Indiana McMullen on Willett, 'The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid into Alabama' Review published on Monday, May 1, 2000 Robert L. Willett, Jr. The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid into Alabama. Carmel: Guild Press of Indiana, 1999. 232 pp. $18.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-57860-025-0. Reviewed by Glenn L. McMullen (Curator of Manuscripts and Archives, Indiana Historical Society) Published on H-Indiana (May, 2000) A Union Cavalry Raid Steeped in Misfortune Robert L. Willett's The Lightning Mule Brigade is the first book-length treatment of Indiana Colonel Abel D. Streight's Independent Provisional Brigade and its three-week raid in spring 1863 through Northern Alabama to Rome, Georgia. The raid, the goal of which was to cut Confederate railroad lines between Atlanta and Chattanooga, was, in Willett's words, a "tragi-comic war episode" (8). The comic aspects stemmed from the fact that the raiding force was largely infantry, mounted not on horses but on fractious mules, anything but lightning-like, justified by military authorities as necessary to take it through the Alabama mountains. Willett's well-written and often moving narrative shifts between the forces of the two Union commanders (Streight and Brig. Gen. Grenville Dodge) and two Confederate commanders (Col. Phillip Roddey and Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest) who were central to the story, staying in one camp for a while, then moving to another. The result is a highly textured and complex, but enjoyable, narrative. Abel Streight, who had no formal military training, was proprietor of the Railroad City Publishing Company and the New Lumber Yard in Indianapolis when the war began. -

Universality of Jurisdiction Over War Crimes

California Law Review VOLUME XXXIII JUNE, 1945 NumBm 2 Universality of Jurisdiction Over War Crimes Willard B. Cowles* B ECAUSE of the mobility of troops in the present war and the practice of transferring troops from one front to another, it may well be that units of Gestapo, SS, or other German organizations, which have been charged with committing some of the worst war crimes, may have been moved from one front to another, perhaps as "flying squad- rons". It may also be a fact that many, even hundreds of, members of such groups have now been captured and are prisoners of war in Great Britain or the United States. Such prisoners held by Great Britain may have committed atrocities against Yugoslavs in Yugo- slavia or Greeks in Greece. German prisoners in the custody of the United States may have committed atrocities against Poles in Poland before the United States became a belligerent. Furthermore, for rea- sons not obvious, but none the less real, it may be that some countries will not wish to punish certain war criminals or that they would prefer that some such individuals be punished by other States. Again, the custodian State may wish to punish an offender itself rather than turn him over to another government even though a request for rendition has been made. Because of notions of territorial jurisdiction, it is thought by some persons that, although a State may punish war criminals for offenses committed against its own armed forces during the military opera- tions, it may not punish an offender when the victim of a criminal act was not a member of its forces, if the crime was committed in a place over which, at the time of the act, the punishing State did not have *Lt. -

The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am

American Indian Law Review Volume 35 | Number 1 1-1-2010 Values in Transition: The hirC icahua Apache from 1886-1914 John W. Ragsdale Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation John W. Ragsdale Jr., Values in Transition: The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am. Indian L. Rev. (2010), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol35/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VALUES IN TRANSITION: THE CHIRICAHUA APACHE FROM 1886-1914 John W Ragsdale, Jr.* Abstract Law confirms but seldom determines the course of a society. Values and beliefs, instead, are the true polestars, incrementally implemented by the laws, customs, and policies. The Chiricahua Apache, a tribal society of hunters, gatherers, and raiders in the mountains and deserts of the Southwest, were squeezed between the growing populations and economies of the United States and Mexico. Raiding brought response, reprisal, and ultimately confinement at the loathsome San Carlos Reservation. Though most Chiricahua submitted to the beginnings of assimilation, a number of the hardiest and least malleable did not. Periodic breakouts, wild raids through New Mexico and Arizona, and a labyrinthian, nearly impenetrable sanctuary in the Sierra Madre led the United States to an extraordinary and unprincipled overreaction. -

2011-Summer Timelines

OMENA TIMELINES Remembering Omena’s Generals and … The American Civil War Sesquicentennial A PUBLICATION OF THE OMENA HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 2011 From the Editor Jim Miller s you can see, our Timelines publica- tion has changed quite a bit. We have A taken it from an institutional “newslet- ter” to a full-blown magazine. To make this all possible, we needed to publish it annually rather than bi-annually. By doing so, we will be able to provide more information with an historical focus rather than the “news” focus. Bulletins and OHS news will be sent in multiple ways; by e-mail, through our website, published in the Leelanau Enterprise or through special mailings. We hope you like our new look! is the offi cial publication Because 2011 is the sesquicentennial year for Timelines of the Omena Historical Society (OHS), the start of the Civil War, it was only fi tting authorized by its Board of Directors and that we provide appropriately related matter published annually. for this issue. We are focusing on Omena’s three Civil War generals and other points that should Mailing address: pique your interest. P.O. Box 75 I want to take this opportunity to thank Omena, Michigan 49674 Suzie Mulligan for her hard work as the long- www.omenahistoricalsociety.com standing layout person for Timelines. Her sage Timelines advice saved me on several occasions and her Editor: Jim Miller expertise in laying out Timelines has been Historical Advisor: Joey Bensley invaluable to us. Th anks Suzie, I truly appre- Editorial Staff : Joan Blount, Kathy Miller, ciate all your help. -

REPORT: [To Accompany Bill H

45TH CONGREss, } HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. REPORT 2d Session. { No. 465. D. G. & D. A. SANFORD. APRIL 5, 1878.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole Honse and ordered to be printed. Mr. MORGAN, from the Committee on Indian Affairs, submitted the fol lowing REPORT: [To accompany bill H. R. 4241.] The Committee on Indian Affairs, to whom was referred the petition for the relief of D. G. & D. A. Sanford, report: That Messrs. D. G. & D. A. Sanford have been engaged for years as cattle-drivers, and on or about the 12th day of June, 1872, they started from ~he county of San Saba, in Texas, with 2, 782 head of cattle for California. They also had with them 38 horses and mules, 4 yoke of oxen, and 2 wagons, which contained their provisions and outfit. On · the lOth day of July they applied to Maj. John P. Hatch, com manding United States troops at Fort Concho, for a military escort across the Staked Plains. The escort was promised them on their arri val at the fort, but upon their arrival, that .officer advised them to pro ceed with ·their herd, and, as one of the petitioners swears, promised them an escort which would overtake them on· the 13th. They, under this advice, drove their herd about twelve miles and went into camp to await the arrival of the promised escort, when at about one o'clock on the morning of the 14th they were attacked by a large body of India,ns, a part of whom drove in the herders, while the others drove off the stock. -

Texas Forts Trail Region

CatchCatch thethe PioPionneereer SpiritSpirit estern military posts composed of wood and While millions of buffalo still roamed the Great stone structures were grouped around an Plains in the 1870s, underpinning the Plains Indian open parade ground. Buildings typically way of life, the systematic slaughter of the animals had included separate officer and enlisted troop decimated the vast southern herd in Texas by the time housing, a hospital and morgue, a bakery and the first railroads arrived in the 1880s. Buffalo bones sutler’s store (provisions), horse stables and still littered the area and railroads proved a boon to storehouses. Troops used these remote outposts to the bone trade with eastern markets for use in the launch, and recuperate from, periodic patrols across production of buttons, meal and calcium phosphate. the immense Southern Plains. The Army had other motivations. It encouraged Settlements often sprang up near forts for safety the kill-off as a way to drive Plains Indians onto and Army contract work. Many were dangerous places reservations. Comanches, Kiowas and Kiowa Apaches with desperate characters. responded with raids on settlements, wagon trains and troop movements, sometimes kidnapping individuals and stealing horses and supplies. Soldiers stationed at frontier forts launched a relentless military campaign, the Red River War of 1874–75, which eventually forced Experience the region’s dramatic the state’s last free Native Americans onto reservations in present-day Oklahoma. past through historic sites, museums and courthouses — as well as historic downtowns offering unique shopping, dining and entertainment. ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ ★★ 2 The westward push of settlements also relocated During World War II, the vast land proved perfect cattle drives bound for railheads in Kansas and beyond. -

Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010

Description of document: US Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010 Requested date: 07-August-2010 Released date: 15-August-2010 Posted date: 23-August-2010 Title of document Impersonal Names Index Listing Source of document: Commander U.S. Army Intelligence & Security Command Freedom of Information/Privacy Office ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 4552 Pike Road Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755-5995 Fax: (301) 677-2956 Note: The IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents INSCOM investigative files that are not titled with the name of a person. Each item in the IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents a file in the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository. You can ask for a copy of the file by contacting INSCOM. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. -

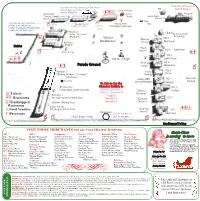

Site Guide.Pub

Gingerbread House & Discover Christmas Using your Five Senses TB Cookie Display Miss Birdie’s Tea Party Santa’s House Santa's Workshop Hut Commissary Ruffini Hospital “Frontier House” House Horse Rides Merchants Petting Zoo Train Lions Pancakes with Santa (Sat) Headquarters Stop ATM Quartermaster A Night at the Stables (Sat) Student Art Show Food Photographs with Santa Cowboy Chuckwagon Breakfast (Sun) Court Cowboy Church Service (Sun) Barracks 6 Mess Hall 6 Chapel “Sutlers’ Christmas” Entertainment & Services Merchants “Winter OQ 9 ”Mexican Rendezvous” Merchants Mess Hall 5 Barracks 5 House” Stables Exhibits ”Czech House” OQ 8 Merchants Boot Camp OQ 7 Indian Village Staff Offices ”German OQ 6 Parade Ground House” Merchants OQ 5 Barracks 2 Living (Ruins) “Buffalo Soldiers’ Christmas” Nativity Merchants Verizon/GTE OQ 4 Volunteer Base Ball Danner Museum Parking Be Sure to See the Exhibits Kettle Corn Historical Exhibits in OQ 3 + Chuck Wagon Old Fashioned Soda Officers’ Quarters 3 ”Officers’ Exhibits Officers’ Quarters 4 Tickets Christmas” Barracks 1 Hospital Restrooms Arc Light Entertainment Area Barracks 1 Volunteer OQ 2 Handicapped Historical Walking Tours Barracks 5 Check in Restrooms Visitor Center, Food Vendors Gift Shop & Information ”Victorian OQ 1 Bandstand House” Beverages Concho Cowboy Co. Merchants Chuck Wagon Camp Old St. Angela Handicapped Parking VISIT THESE MERCHANTS FOR ALL YOUR HOLIDAY SHOPPING OQ 1 OQ 9 Commissary Barracks 2 East Barracks 2 West Food Vendors Santa Claus Calico Apothecary English’s Photography Southwest Collections 1 of One John Mark Candles Amadeo Cuisine is coming to town Carmelite Hermits’ Kitchen Message in Mesquite Usborne Books & More Geese of a Feather Dorothy’s Creations Cristi & Ali Cuisine Gypsy Chix Rowdy Rose Boutique Fork It Over Majeza Jewelry Cleaner Mom’s Madness Vittle Barn Susan Kemper Art Barracks 6 Tracy’s Studio Lilla Rose Hair Heroes Long Horn Coffee Co. -

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-09-2 Volume 35 Number 2 April - June 2009

MIPB April - June 2009 PB 34-O9-2 Operations in OEF Afghanistan FROM THE EDITOR In this issue, three articles offer perspectives on operations in Afghanistan. Captain Nenchek dis- cusses the philosophy of the evolving insurgent “syndicates,” who are working together to resist the changes and ideas the Coalition Forces bring to Afghanistan. Captain Beall relates his experiences in employing Human Intelligence Collection Teams at the company level in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Lieutenant Colonel Lawson provides a look into the balancing act U.S. Army chaplains as non-com- batants in Afghanistan are involved in with regards to Information Operations. Colonel Reyes discusses his experiences as the MNF-I C2 CIOC Chief, detailing the problems and solutions to streamlining the intelligence effort. First Lieutenant Winwood relates her experiences in integrating intelligence support into psychological operations. From a doctrinal standpoint, Lieutenant Colonels McDonough and Conway review the evolution of priority intelligence requirements from a combined operations/intelligence view. Mr. Jack Kem dis- cusses the constructs of assessment during operations–measures of effectiveness and measures of per- formance, common discussion threads in several articles in this issue. George Van Otten sheds light on a little known issue on our southern border, that of the illegal im- migration and smuggling activities which use the Tohono O’odham Reservation as a corridor and offers some solutions for combined agency involvement and training to stem the flow. Included in this issue is nomination information for the CSM Doug Russell Award as well as a biogra- phy of the 2009 winner. Our website is at https://icon.army.mil/ If your unit or agency would like to receive MIPB at no cost, please email [email protected] and include a physical address and quantity desired or call the Editor at 520.5358.0956/DSN 879.0956. -

FOR the RECORDS Common Legal Doctrine in the Colonial and Early United States

VOL. 11, NO. 9 — SEPTEMBER 2019 From the dower release in a deed acknowledgement in Frederick Co., Maryland: “Louisa wife of the said John Weaver being examined apart From her said husband relinquished her right of Dower to the said Lott or portion of ground and Acknowledged that she did freely and Willingly without being Induced thereto by coercion of her said Husband or for Fear of his Displeasure.” Source: Frederick County, Maryland. Liber K: 109. John Weaver to Michael Hare, 24th October 1775. Office of Recorder of Deeds, Frederick County, Maryland. Adopted from English common law, coverture was the FOR THE RECORDS common legal doctrine in the colonial and early United States. Depending on the colony (state or territory), the “Freely and without coercion”— practice adopted a more strict (Massachusetts), progres- Deed records under coverture sive (middle colonies) or conservative (southern colonies) approach to the rights of a feme covert and her right to “Coverture” (sometimes spelled “couverture”) was a legal property. doctrine whereby a married woman’s status as “feme cov- ert” (a married woman) removed her rights and obligations The southern colonies “accepted the existence of coer- and transferred them to her husband. This legal principle cion” while “effectively … [keeping] women in a subser- created records that can reveal information about ancestors vient position”1 by developing overprotective laws that and uncover clues that can break through brick walls. treated femes covert as helpless. These colonies empha- sized precision in record keeping ensuring the certainty of Background land title. A feme covert had no rights to own property, litigate, own a business.