John Exshaw.3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Matieland to Mother City: Landscape, Identity and Place in Feature Films Set in the Cape Province, 1947-1989.”

“FROM MATIELAND TO MOTHER CITY: LANDSCAPE, IDENTITY AND PLACE IN FEATURE FILMS SET IN THE CAPE PROVINCE, 1947-1989.” EUSTACIA JEANNE RILEY Thesis Presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Historical Studies UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN December 2012 Supervisor: Vivian Bickford-Smith Table of Contents Abstract v Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 1 The Cape apartheid landscape on film 4 2 Significance and literature review 9 3 Methodology 16 3.1 Films as primary sources 16 3.2 A critical visual methodology 19 4 Thesis structure and chapter outline 21 Chapter 1: Foundational Cape landscapes in Afrikaans feature films, 1947- 1958 25 Introduction 25 Context 27 1 Afrikaner nationalism and identity in the rural Cape: Simon Beyers, Hans die Skipper and Matieland 32 1.1 Simon Beyers (1947) 34 1.2 Hans die Skipper (1953) 41 1.3 Matieland (1955) 52 2 The Mother City as a scenic metropolitan destination and military hub: Fratse in die Vloot 60 Conclusion 66 Chapter 2: Mother city/metropolis: representations of the Cape Town land- and cityscape in feature films of the 1960s 69 Introduction 69 Context 70 1 Picturesque Cape Town 76 1.1 The exotic picturesque 87 1.2 The anti-picturesque 90 1.3 A picturesque for Afrikaners 94 2 Metropolis of Tomorrow 97 2.1 Cold War modernity 102 i Conclusion 108 Chapter 3: "Just a bowl of cherries”: representations of landscape and Afrikaner identity in feature films made in the Cape Province in the 1970s 111 Introduction 111 Context 112 1 A brief survey of 1970s film landscapes 118 2 Picturesque -

Scapigliatura

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Baudelairism and Modernity in the Poetry of Scapigliatura Alessandro Cabiati PhD The University of Edinburgh 2017 Abstract In the 1860s, the Italian Scapigliati (literally ‘the dishevelled ones’) promoted a systematic refusal of traditional literary and artistic values, coupled with a nonconformist and rebellious lifestyle. The Scapigliatura movement is still under- studied, particularly outside Italy, but it plays a pivotal role in the transition from Italian Romanticism to Decadentism. One of the authors most frequently associated with Scapigliatura in terms of literary influence as well as eccentric Bohemianism is the French poet Charles Baudelaire, certainly amongst the most innovative and pioneering figures of nineteenth-century European poetry. Studies on the relationship between Baudelaire and Scapigliatura have commonly taken into account only the most explicit and superficial Baudelairian aspects of Scapigliatura’s poetry, such as the notion of aesthetic revolt against a conventional idea of beauty, which led the Scapigliati to introduce into their poetry morally shocking and unconventional subjects. -

Erenews 2020 3 1

ISSN 2531-6214 EREnews© vol. XVIII (2020) 3, 1-45 European Religious Education newsletter July - August - September 2020 Eventi, documenti, ricerche, pubblicazioni sulla gestione del fattore religioso nello spazio pubblico educativo e accademico in Europa ■ Un bollettino digitale trimestrale plurilingue ■ Editor: Flavio Pajer [email protected] EVENTS & DOCUMENTS EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS Guide on Art 2: Respect of parental rights, 2 CONSEIL DE L’EUROPE / CDH Une éducation sexuelle complète protège les enfants, 2 EUROPEAN COMMISSION Racial discrimination in education and EU equality law. Report 2020, 3 WCC-PCID Serving a wounded world in interreligious solidarity. A Christian call to reflection, 3 UNICEF-RELIGIONS FOR PEACE Launch of global multireligious Faith-in-Action Covid initiative, 3 OIEC Informe 2020 sobre la educacion catolica mundial en tiempos de crisis, 4 WORLD VALUES SURVEY ASSOCIATION European Values Study. Report 2917-2021, 4 USCIRF Releases new Report about conscientious objection, 4 PEW RESEARCH CENTER Between belief in God and morality: what connection? 4 AGENCY FOR FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS Fighting discrimination on grounds of religion and ethnicity 5 EUROPEAN WERGELAND CENTER 2019 Annual Report, 5 WORLD BANK GROUP / Education Global Practice Simulating the potential impacts of Covid, 5 AMERICAN ACADEMY OF RELIGION AAR Religious Literacy Guidelines, 2020, 6 CENTRE FOR MEDIA MONITORING APPG Religion in the Media inquiry into religious Literacy, 6 NATIONAL CHRONICLES DEUTSCHLAND / NSW Konfessionelle Kooperation in Religionsunterricht, -

The Dracula Film Adaptations

DRACULA IN THE DARK DRACULA IN THE DARK The Dracula Film Adaptations JAMES CRAIG HOLTE Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Number 73 Donald Palumbo, Series Adviser GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Science Fiction and Fantasy Robbe-Grillet and the Fantastic: A Collection of Essays Virginia Harger-Grinling and Tony Chadwick, editors The Dystopian Impulse in Modern Literature: Fiction as Social Criticism M. Keith Booker The Company of Camelot: Arthurian Characters in Romance and Fantasy Charlotte Spivack and Roberta Lynne Staples Science Fiction Fandom Joe Sanders, editor Philip K. Dick: Contemporary Critical Interpretations Samuel J. Umland, editor Lord Dunsany: Master of the Anglo-Irish Imagination S. T. Joshi Modes of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Twelfth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Robert A. Latham and Robert A. Collins, editors Functions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Thirteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Joe Sanders, editor Cosmic Engineers: A Study of Hard Science Fiction Gary Westfahl The Fantastic Sublime: Romanticism and Transcendence in Nineteenth-Century Children’s Fantasy Literature David Sandner Visions of the Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Fifteenth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts Allienne R. Becker, editor The Dark Fantastic: Selected Essays from the Ninth International Conference on the Fantastic in the Arts C. W. Sullivan III, editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Holte, James Craig. Dracula in the dark : the Dracula film adaptations / James Craig Holte. p. cm.—(Contributions to the study of science fiction and fantasy, ISSN 0193–6875 ; no. -

Australian Radio Series

Radio Series Collection Guide1 Australian Radio Series 1930s to 1970s A guide to ScreenSound Australia’s holdings 1 Radio Series Collection Guide2 Copyright 1998 National Film and Sound Archive All rights reserved. No reproduction without permission. First published 1998 ScreenSound Australia McCoy Circuit, Acton ACT 2600 GPO Box 2002, Canberra ACT 2601 Phone (02) 6248 2000 Fax (02) 6248 2165 E-mail: [email protected] World Wide Web: http://www.screensound.gov.au ISSN: Cover design by MA@D Communication 2 Radio Series Collection Guide3 Contents Foreword i Introduction iii How to use this guide iv How to access collection material vi Radio Series listing 1 - Reference sources Index 3 Radio Series Collection Guide4 Foreword By Richard Lane* Radio serials in Australia date back to the 1930s, when Fred and Maggie Everybody, Coronets of England, The March of Time and the inimitable Yes, What? featured on wireless sets across the nation. Many of Australia’s greatest radio serials were produced during the 1940s. Among those listed in this guide are the Sunday night one-hour plays - The Lux Radio Theatre and The Macquarie Radio Theatre (becoming the Caltex Theatre after 1947); the many Jack Davey Shows, and The Bob Dyer Show; the Colgate Palmolive variety extravaganzas, headed by Calling the Stars, The Youth Show and McCackie Mansion, which starred the outrageously funny Mo (Roy Rene). Fine drama programs produced in Sydney in the 1940s included The Library of the Air and Max Afford's serial Hagen's Circus. Among the comedy programs listed from this decade are the George Wallace Shows, and Mrs 'Obbs with its hilariously garbled language. -

Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Journeys into Perversion: Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco Glenn Ward Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex May 2011 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 3 Summary Due to their characteristic themes (such as „perverse‟ desire and monstrosity) and form (incoherence and excess), exploitation films are often celebrated as inherently subversive or transgressive. I critically assess such claims through a close reading of the films of the Spanish „sex and horror‟ specialist Jess Franco. My textual and contextual analysis shows that Franco‟s films are shaped by inter-relationships between authorship, international genre codes and the economic and ideological conditions of exploitation cinema. Within these conditions, Franco‟s treatment of „aberrant‟ and gothic desiring subjectivities appears contradictory. Contestation and critique can, for example, be found in Franco‟s portrayal of emasculated male characters, and his female vampires may offer opportunities for resistant appropriation. -

Register of Entertainers, Actors and Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa

Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuun1988_10 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Register of Entertainers, Actors And Others Who Have Performed in Apartheid South Africa Alternative title Notes and Documents - United Nations Centre Against ApartheidNo. 11/88 Author/Creator United Nations Centre against Apartheid Publisher United Nations, New York Date 1988-08-00 Resource type Reports Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1981 - 1988 Source Northwestern University Libraries Description INTRODUCTION. REGISTER OF ENTERTAINERS, ACTORS AND OTHERS WHO HAVE PERFORMED IN APARTHEID SOUTH AFRICA SINCE JANUARY 1981. -

Hellsing Free Download

Hellsing free download click here to download Hellsing Episode List. Watch Full Episodes of Hellsing at Soul-Anime. Hellsing is the best website to watch Hellsing!!! download or watch full episodes for free. Watch Full Episodes of Hellsing Subbed at Soul-Anime. Hellsing Ultimate 9 website to watch Hellsing Subbed!!! download or watch full episodes for free. Watch Hellsing Ultimate Episode 4 English Dub, Sub Full Movie, Episodes - KissAnime. Watch and Download Free Anime Streaming Online Kiss Anime. Watch Hellsing Ultimate Episode 10 English Dub, Sub Full Movie, Episodes - KissAnime. Watch and Download Free Anime Streaming Online Kiss Anime. Hellsing Ultimate Ova Background For Free Download. Hellsing Ultimate Abridged quotes >>> it's funny bc he was talking about the frikin nazi in this scene. hellsing ringtones for mobile phones - most downloaded last month - Free download on Zedge. Download Hellsing volume (manga) www.doorway.ru NOTE: The songs on the "Shuffle Day To Day EP" are in extra high mp3 quality ( kbs/s and 44 KHz) so the file is pretty big ( mb)! But we think it's worth it! download free! DOWNLOAD LINK ===> www.doorway.ru Transcript of cor ova hellsing ultimate download free! www.doorway.ru Download Hellsing Ultimate Uncensored Bluray [BD] p MB | p MB MKV Soulreaperzone | Free Mini MKV Anime Direct Downloads. English. Book 1 of 10 in the Hellsing - in English (Dark Horse Manga) Series . Don't have a Kindle? Get your Kindle here, or download a FREE Kindle Reading App. In , it was announced that Geneon, along with the co-operation and blessing of Hellsing creator Kohta Hirano, would produce an OVA series based on the. -

Of Titles (PDF)

Alphabetical index of titles in the John Larpent Plays The Huntington Library, San Marino, California This alphabetical list covers LA 1-2399; the unidentified items, LA 2400-2502, are arranged alphabetically in the finding aid itself. Title Play number Abou Hassan 1637 Aboard and at Home. See King's Bench, The 1143 Absent Apothecary, The 1758 Absent Man, The (Bickerstaffe's) 280 Absent Man, The (Hull's) 239 Abudah 2087 Accomplish'd Maid, The 256 Account of the Wonders of Derbyshire, An. See Wonders of Derbyshire, The 465 Accusation 1905 Aci e Galatea 1059 Acting Mad 2184 Actor of All Work, The 1983 Actress of All Work, The 2002, 2070 Address. Anxious to pay my heartfelt homage here, 1439 Address. by Mr. Quick Riding on an Elephant 652 Address. Deserted Daughters, are but rarely found, 1290 Address. Farewell [for Mrs. H. Johnston] 1454 Address. Farewell, Spoken by Mrs. Bannister 957 Address. for Opening the New Theatre, Drury Lane 2309 Address. for the Theatre Royal Drury Lane 1358 Address. Impatient for renoun-all hope and fear, 1428 Address. Introductory 911 Address. Occasional, for the Opening of Drury Lane Theatre 1827 Address. Occasional, for the Opening of the Hay Market Theatre 2234 Address. Occasional. In early days, by fond ambition led, 1296 Address. Occasional. In this bright Court is merit fairly tried, 740 Address. Occasional, Intended to Be Spoken on Thursday, March 16th 1572 Address. Occasional. On Opening the Hay Marker Theatre 873 Address. Occasional. On Opening the New Theatre Royal 1590 Address. Occasional. So oft has Pegasus been doom'd to trial, 806 Address. -

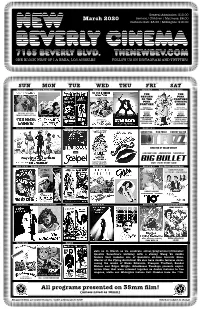

Newbev202003 FRONT

General Admission: $12.00 March 2020 Seniors / Children / Matinees: $8.00 NEW Cartoon Club: $8.00 / Midnights: $10.00 BEVERLY cinema 7165 BEVERLY BLVD. THENEWBEV.COM ONE BLOCK WEST OF LA BREA, LOS ANGELES FOLLOW US ON INSTAGRAM AND TWITTER! SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT March 1 & 2 Directed by Randal Kleiser March 3 March 4 & 5 March 6 & 7 Blake Edwards / Peter Sellers THE THE RETURN PINK OF THE PANTHER PINK STRIKES PANTHER AGAIN DIRECTED BY DIRECTED BY BLAKE EDWARDS BLAKE EDWARDS STARRING STARRING BROOKE SHIELDS PETER PETER CHRISTOPHER ATKINS SELLERS SELLERS CHRISTOPHER HERBERT LOM JOHN HUSTON’S PLUMMER COLIN BLAKELY CATHERINE SCHELL LEONARD ROSSITER HERBERT LOM LESLEY-ANNE DOWN March 8 & 9 Directed by Blake Edwards March 10 March 11 & 12 March 13 & 14 SIMON PEGG NICK FROST TIMOTHY DALTON DIRECTED BY EDGAR WRIGHT PLUS! BIGLAU CHING-WAN BULLET JORDAN CHAN THERESA LEE UGO TOGNAZZI MICHEL SERRAULT DIRECTED BY BENNY CHAN March 15 & 16 Barbara Stanwyck Double Feature March 17 March 18 & 19 March 20 & 21 Blake Edwards / Dudley Moore DUDLEY MOORE AMY IRVING ANN REINKING DUDLEY MOORE JULIE ANDREWS BO DEREK March 22 & 23 Directed by François Truffaut March 24 March 25 & 26 March 27 & 28 Quentin’s Birthday Double Feature JIMMY WANG YU Written, Directed by, and Starring Written & Directed by JIMMY WANG YU LO WEI March 29 & 30 March 31 Join us in March as we celebrate owner/programmer/fi lmmaker Quentin Tarantino’s birthday with a Jimmy Wang Yu double IB Tech Print feature that includes one of Quentin’s all-time favorite fi lms, IB Tech Print Master of the Flying Guillotine! We also have double features show- casing the works of Blake Edwards, François Truff aut, Randal Kleiser and Edgar Wright. -

Language and the Construction of Power and Knowledge in Vampire Fiction

A “Truth Like This”: Language and the Construction of Power and Knowledge in Vampire Fiction Jutta Schulze Hannover, Germany Abstract : The paper examines the relationship between power, knowledge, and language in Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight from the vantage point of discourses on vampirism. Based on Michel Foucault’s notion of power as a localized, ubiquitous, and heterogeneous set of social strategies, it discusses the constitutive role of language in the construction of power relationships, focusing on gender and sexual relationships in both novels. In Dracula , the patriarchal system functions as a dominant discourse which prescribes legitimate sexual relations for women, while vampirism threatens this order by pointing out its gaps and inconsistencies. Revealing the ‘in-between’ of this order’s dichotomous relations, the rupture of its supposed coherence and ‘naturalness’ manifests itself through the notion of desire. Desire shares important features with language, as it is characterized by difference and deferral. Despite its appearance as an alternative social order, the interplay between power, knowledge, and language in Twilight suggests similar restrictions to female sexuality. This discourse on vampirism and sexuality is constructed by Edward and Bella, but is decisively mediated through Bella’s narrative voice. Their collaboration establishes a relationship of power which casts Bella in a state of weakness and submissiveness but also shows how language and knowledge may transform power relationships. ampires have captivated the attention of readers, writers, and critics for centuries. As literary figures, vampires fascinate due to the powerful but subtle Vmanner in which they reflect upon a particular societal order—its precepts, prohibitions, and fears—and thus make visible the cultural and social dynamics in relation to the individual subject. -

Spiel's Noch Einmal, Ennio! Zu Besuch Bei Maestro Morricone in Der

Spiel's noch einmal, Ennio! Zu Besuch bei Maestro Morricone in der "ewigen Stadt" Von Marc Hairapetian Ennio Morricone & THE SPIRIT aka Marc Hairapetian (Foto: Vo Nguyen Kieu Oanh für SPIRIT - EIN LÄCHELN IM STURM) In Rom kommt in der allgemeinen Gunst zuerst der Papst Franziskus, gleich danach aber Ennio Morricone. Ehrfürchtig fragt einen der Hotelier: "Erwartet Sie wirklich morgen der Maestro bei sich zu Hause?" Klassiker des Italowesterns wie "Zwei glorreiche Halunken" (1966), "Spiel mir das Lied vom Tod" (1968) oder "Leichen pflastern seinen Weg" (ebenfalls 1968) sind untrennbar mit seinen innovativ-coolen Kompositionen verbunden. Dabei machen die Soundtracks für dieses Genre nur einen Bruchteil seines gewaltigen Gesamtwerks aus, das auch nicht-filmmusikalische, avantgardistische Aufnahmen des Anton-Webern-Verehrers beinhaltet. Der am 10. November 1928 im römischen Stadtteil Trastevere geborene ehemalige Trompeter hat für annähernd alle bedeutenden Regisseure der letzten sechs Jahrzehnte Scores geschrieben und sogar Popbands wie auch Vertreter der Clubszene mit seinen unorthodoxen, mitunter durchaus tanzbaren Klängen inspiriert. Nur selten gibt er Interviews und erst recht nicht in seinem Anwesen im Herzen der "ewigen Stadt", das in seiner Pracht fast einem Palazzo gleicht und neben Morricone und seiner Frau von uniformierten Bediensteten bevölkert wird. Ausnahmen bestätigen die Regel: Diesmal lud das vielleicht größte Genie der Filmmusik Marc Hairapetian an einem spätsommerlich heißen Septembertag zu einem Hausbesuch ein. Der schmächtige