The Celtic Harp at Stonehenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume II

7+( &(/7,& (1&<&/23(',$ 92/80( ,, . T H E C E L T I C E N C Y C L O P E D I A © HARRY MOUNTAIN VOLUME II UPUBLISH.COM 1998 Parkland, Florida, USA The Celtic Encyclopedia © 1997 Harry Mountain Individuals are encouraged to use the information in this book for discussion and scholarly research. The contents may be stored electronically or in hardcopy. However, the contents of this book may not be republished or redistributed in any form or format without the prior written permission of Harry Mountain. This is version 1.0 (1998) It is advisable to keep proof of purchase for future use. Harry Mountain can be reached via e-mail: [email protected] postal: Harry Mountain Apartado 2021, 3810 Aveiro, PORTUGAL Internet: http://www.CeltSite.com UPUBLISH.COM 1998 UPUBLISH.COM is a division of Dissertation.com ISBN: 1-58112-889-4 (set) ISBN: 1-58112-890-8 (vol. I) ISBN: 1-58112-891-6 (vol. II) ISBN: 1-58112-892-4 (vol. III) ISBN: 1-58112-893-2 (vol. IV) ISBN: 1-58112-894-0 (vol. V) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mountain, Harry, 1947– The Celtic encyclopedia / Harry Mountain. – Version 1.0 p. 1392 cm. Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-58112-889-4 (set). -– ISBN 1-58112-890-8 (v. 1). -- ISBN 1-58112-891-6 (v. 2). –- ISBN 1-58112-892-4 (v. 3). –- ISBN 1-58112-893-2 (v. 4). –- ISBN 1-58112-894-0 (v. 5). Celts—Encyclopedias. I. Title. D70.M67 1998-06-28 909’.04916—dc21 98-20788 CIP The Celtic Encyclopedia is dedicated to Rosemary who made all things possible . -

Savannah Scottish Games & Highland Gathering

47th ANNUAL CHARLESTON SCOTTISH GAMES-USSE-0424 November 2, 2019 Boone Hall Plantation, Mount Pleasant, SC Judge: Fiona Connell Piper: Josh Adams 1. Highland Dance Competition will conform to SOBHD standards. The adjudicator’s decision is final. 2. Pre-Premier will be divided according to entries received. Medals and trophies will be awarded. Medals only in Primary. 3. Premier age groups will be divided according to entries received. Cash prizes will be awarded as follows: Group 1 Awards 1st $25.00, 2nd $15.00, 3rd $10.00, 4th $5.00 Group 2 Awards 1st $30.00, 2nd $20.00, 3rd $15.00, 4th $8.00 Group 3 Awards 1st $50.00, 2nd $40.00, 3rd $30.00, 4th $15.00 4. Trophies will be awarded in each group. Most Promising Beginner and Most Promising Novice 5. Dancer of the Day: 4 step Fling will be danced by Premier dancer who placed 1st in any dance. Primary, Beginner and Novice Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 9:00 AM- Competition to begin at 9:30 AM Beginner Steps Novice Steps Primary Steps 1. Highland Fling 4 5. Highland Fling 4 9. 16 Pas de Basque 2. Sword Dance 2&1 6. Sword Dance 2&1 10. 6 Pas de Basque & 4 High Cuts 3. Seann Triubhas 3&1 7. Seann Triubhas 3&1 11. Highland Fling 4 4. 1/2 Tulloch 8. 1/2 Tulloch 12. Sword Dance 2&1 Intermediate and Premier Registration: Saturday, November 2, 2019, 12:30 PM- Competition to begin at 1:00 PM Intermediate Premier 15 Jig 3&1 20 Hornpipe 4 16 Hornpipe 4 21 Jig 3&1 17 Highland Fling 4 22. -

Stories from Early Irish History

1 ^EUNIVERJ//, ^:IOS- =s & oo 30 r>ETRr>p'S LAMENT. A Land of Heroes Stories from Early Irish History BY W. LORCAN O'BYRNE WITH SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN E. BACON BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED LONDON GLASGOW AND DUBLIN n.-a INTEODUCTION. Who the authors of these Tales were is unknown. It is generally accepted that what we now possess is the growth of family or tribal histories, which, from being transmitted down, from generation to generation, give us fair accounts of actual events. The Tales that are here given are only a few out of very many hundreds embedded in the vast quantity of Old Gaelic manuscripts hidden away in the libraries of nearly all the countries of Europe, as well as those that are treasured in the Royal Irish Academy and Trinity College, Dublin. An idea of the extent of these manuscripts may be gained by the statement of one, who perhaps had the fullest knowledge of them the late Professor O'Curry, in which he says that the portion of them (so far as they have been examined) relating to His- torical Tales would extend to upwards of 4000 pages of large size. This great mass is nearly all untrans- lated, but all the Tales that are given in this volume have already appeared in English, either in The Publications of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language] the poetical versions of The IV A LAND OF HEROES. Foray of Queen Meave, by Aubrey de Vere; Deirdre', by Dr. Robert Joyce; The Lays of the Western Gael, and The Lays of the Red Branch, by Sir Samuel Ferguson; or in the prose collection by Dr. -

Rhythm Bones Player a Newsletter of the Rhythm Bones Society Volume 10, No

Rhythm Bones Player A Newsletter of the Rhythm Bones Society Volume 10, No. 3 2008 In this Issue The Chieftains Executive Director’s Column and Rhythm As Bones Fest XII approaches we are again to live and thrive in our modern world. It's a Bones faced with the glorious possibilities of a new chance too, for rhythm bone players in the central National Tradi- Bones Fest in a new location. In the thriving part of our country to experience the camaraderie tional Country metropolis of St. Louis, in the ‗Show Me‘ state of brother and sisterhood we have all come to Music Festival of Missouri, Bones Fest XII promises to be a expect of Bones Fests. Rhythm Bones great celebration of our nation's history, with But it also represents a bit of a gamble. We're Update the bones firmly in the center of attention. We betting that we can step outside the comfort zones have an opportunity like no other, to ride the where we have held bones fests in the past, into a Dennis Riedesel great Mississippi in a River Boat, and play the completely new area and environment, and you Reports on bones under the spectacular arch of St. Louis. the membership will respond with the fervor we NTCMA But this bones Fest represents more than just have come to know from Bones Fests. We're bet- another great party, with lots of bones playing ting that the rhythm bone players who live out in History of Bones opportunity, it's a chance for us bone players to Missouri, Kansas, Illinois, Oklahoma, and Ne- in the US, Part 4 relive a part of our own history, and show the braska will be as excited about our foray into their people of Missouri that rhythm bones continue (Continued on page 2) Russ Myers’ Me- morial Update Norris Frazier Bones and the Chieftains: a Musical Partnership Obituary What must surely be the most recognizable Paddy Maloney. -

Compton Music Stage

COMPTON STAGE-Saturday, Sept. 18, FSU Upper Quad 10:20 AM Bear Hill Bluegrass Bear Hill Bluegrass takes pride in performing traditional bluegrass and gospel, while adding just the right mix of classic country and comedy to please the audience and have fun. They play the familiar bluegrass, gospel and a few country songs that everyone will recognize, done in a friendly down-home manner on stage. The audience is involved with the band and the songs throughout the show. 11:00 AM The Jesse Milnes, Emily Miller, and Becky Hill Show This Old-Time Music Trio re-envisions percussive dance as another instrument and arrange traditional old-time tunes using foot percussion as if it was a drum set. All three musicians have spent significant time in West Virginia learning from master elder musicians and dancers and their goal with this project is to respect the tradition the have steeped themselves in while pushing the boundaries of what old-time music is. 11:45 AM Ken & Brad Kolodner Quartet Regarded as one of the most influential hammered dulcimer players, Baltimore’s Ken Kolodner has performed and toured for the last ten years with his son Brad Kolodner, one of the finest practitioners of the clawhammer banjo, to perform tight and musical arrangements of original and traditional old-time music with a “creative curiosity that lets all listeners know that a passion for traditional music yet thrives in every generation (DPN).” The dynamic father-son duo pushes the boundaries of the Appalachian tradition by infusing their own brand of driving, innovative, tasteful and unique interpretations of traditional and original fiddle tunes and songs. -

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

The Trecento Lute

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title The Trecento Lute Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1kh2f9kn Author Minamino, Hiroyuki Publication Date 2019 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Trecento Lute1 Hiroyuki Minamino ABSTRACT From the initial stage of its cultivation in Italy in the late thirteenth century, the lute was regarded as a noble instrument among various types of the trecento musical instruments, favored by both the upper-class amateurs and professional court giullari, participated in the ensemble of other bas instruments such as the fiddle or gittern, accompanied the singers, and provided music for the dancers. Indeed, its delicate sound was more suitable in the inner chambers of courts and the quiet gardens of bourgeois villas than in the uproarious battle fields and the busy streets of towns. KEYWORDS Lute, Trecento, Italy, Bas instrument, Giullari any studies on the origin of the lute begin with ancient Mesopota- mian, Egyptian, Greek, or Roman musical instruments that carry a fingerboard (either long or short) over which various numbers M 2 of strings stretch. The Arabic ud, first widely introduced into Europe by the Moors during their conquest of Spain in the eighth century, has been suggest- ed to be the direct ancestor of the lute. If this is the case, not much is known about when, where, and how the European lute evolved from the ud. The presence of Arabs in the Iberian Peninsula and their cultivation of musical instruments during the middle ages suggest that a variety of instruments were made by Arab craftsmen in Spain. -

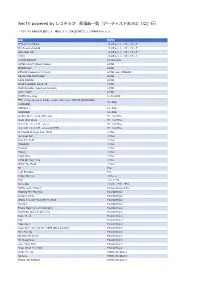

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

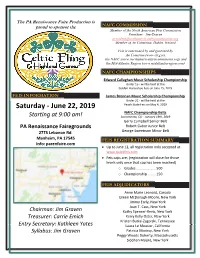

June 22, 2019

The PA Renaissance Faire Production is proud to sponsor the NAFC COMMISSION Member of the North American Feis Commission President: Jim Graven [email protected] Member of An Coimisiun, Dublin, Ireland Feis is sanctioned by and governed by An Comisiun (www.clrg.ie), the NAFC (www.northamericanfeiscommission.org) and the Mid-Atlantic Region (www.midatlanticregion.com) NAFC CHAMPIONSHIPS Edward Callaghan Music Scholarship Championship Under 15 - will be held at the Golden Horseshoe Feis on June 15, 2019 FEIS INFORMATION James Brennan Music Scholarship Championship Under 21 - will be held at the Peach State Feis on May 4, 2019 Saturday - June 22, 2019 NAFC Championship Belts Starting at 9:00 am! Sacramento, CA - January 19th, 2019 Gerry Campbell Senior Belt PA Renaissance Fairegrounds Robert Gabor Junior Belt 2775 Lebanon Rd. George Sweetnam Minor Belt Manheim, PA 17545 FEIS REGISTRATION SUMMARY Info: parenfaire.com Up to June 12, all registration only accepted at www.quickfeis.com Feis caps are: (registration will close for those levels only once that cap has been reached) o Grades ..................... 500 o Championship ......... 150 FEIS ADJUDICATORS Anne Marie Leonard, Canada Eileen McDonagh-Moore, New York Jimmy Early, New York Joan T. Cass, New York Chairman: Jim Graven Kathy Spencer-Revis, New York Treasurer: Carrie Emich Kerry Kelly Oster, New York Kristen Butke-Zagorski, Tennessee Entry Secretary: Kathleen Yates Laura Le Meusier, California Syllabus: Jim Graven Patricia Morissy, New York Peggy Woods Doherty, Massachusetts Siobhan Moore, New York COMPETITION FEES CELTIC FLING FEIS FESTIVAL Feis Admission includes ONE day ticket to the festival Competition Fees FEES (you can purchase a second day ticket at registration) Solo Dancing / TR / Sets / Non-Dance Kick-off concert on Friday featuring great performers! $ 10 Bring your appetite and enjoy delicious foods and (per competitor and per dance) refreshing wines, ales & ciders while listening to the live Preliminary Championship music! Gates open at 4PM. -

Arranged Mafia Marriage Chapter 1 BPOV I Feel Like I Am Always Running from Someone

Arranged Mafia Marriage Chapter 1 BPOV I feel like I am always running from someone. I can feel their eyes watching me. My name is Bella Swan; I am 16 years old and a sophomore in high school. My father is Charlie Swan is Mafia lord and his best friend Carlisle Cullen is his partner in crime who I have heard a lot about over the years. My mother is Renee Swan she is definitely one the sweetest mother's in the world but she can be your worst nightmare if you get on her bad side. I have four older siblings Sam, Jacob, Rose, and Alice. I am the baby of the family which also means I get the most unwanted attention and my siblings have a hard time accepting that I'm not a little girl anymore, I am almost an adult. My ex-boyfriend Chris was murdered when I was 15 years old. He was definitely the sweetest boyfriend you could have, I loved him and wanted to marry him in the future, but that will never happen with him. Many people want me for my families' money, but he wanted me for who I was. The mafia life is what I grew up with living in New York; I learned you can't trust anyone outside of the family except for the Cullen's. I also didn't trust people because of what I had dealt with the past sixteen years. Which brings me here in Chicago at Mr. Cullen's house, my father announced to me last week that I was arranged to be married to Mr. -

News from Around the Region Geraldine Elliott, Director North

Geraldine Elliott, Director North Central Region, AHS 753 Crestwood Dr. Waukesha, WI 53188 262.547.8539 [email protected] A tax-exempt non-profit corporation founded in 1962 Greetings to All Harpists in the North Central Region. I am honored to be your Regional Director at this exciting time in the life of the American Harp Society. Please let me know how I can facilitate communications between and among harpists in the Region. This Newsletter is one means of spreading the word among all the chapters in the Region, but it comes only once a year. There will be a second, email-only, message in the spring, so it is vitally important that we have accurate email addresses for all harpists. We send this newsletter to let you know about harp-happenings that are closer and less expensive (some are even free!) than the National meetings that are coming up. Please let me know of new items that arise so I can include them in the spring email blast. And donʼt forget to send me your accurate email address. THE AMERICAN HARP SOCIETY 9TH SUMMER INSTITUTE AND 19TH NATIONAL COMPETITION JUNE 19-23, 2011 THE LYON AND HEALY AWARDS JUNE 18-19, 2011 DENTON, TX (DALLAS/FT. WORTH AREA) WWW.MUSIC.UNT.EDU/HARP The University of North Texas welcomes the American Harp Society to enjoy a wonderful week. All events will be geared towards students and will include master classes, workshops, ensemble performances and viewing of historic harps. Performances will feature harpists of the Southwest and Emily Mitchell, guest artist and Heidi Van Hoesen Gorton, the AHS Concert Artist, and Michael Colgrass will be guest clinician. -

The Roman Virtues

An Introduction to the Roman Deities Hunc Notate: The cultural organization, the Roman Republic: Res publica Romana, and authors have produced this text for educational purposes. The Res publica Romana is dedicated to the restoration of ancient Roman culture within the modern day. It is our belief that the Roman virtues must be central to any cultural restoration as they formed the foundation of Romanitas in antiquity and still serve as central to western civilization today. This text is offered free of charge, and we give permission for its use for private purposes. You may not offer this publication for sale or produce a financial gain from its distribution. We invite you to share this document freely online and elsewhere. However, if you do share this document we ask that you do so in an unaltered form and clearly give credit to the Roman Republic: Res publica Romana and provide a link to: www.RomanRepublic.org 1 Roman Republic: Res publica Romana| RomanRepublic.org An Introduction to the Roman Deities The existence of the gods is a helpful thing; so let us believe in them. Let us offer wine and incense on ancient altars. The gods do not live in a state of quiet repose, like sleep. Divine power is all around us - Publius Ovidius Naso Dedicated to anyone who desires to build a relationship with the Gods and Goddesses of Rome and to my friends Publius Iunius Brutus & Lucia Hostilia Scaura 2 Roman Republic: Res publica Romana| RomanRepublic.org An Introduction to the Roman Deities Who are the Roman Gods and Goddesses? Since the prehistoric period humans have pondered the nature of the gods.