Conservation and Open Space Element June, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revised Section 4.6 Biological Resources Draft Environmental

Revised Section 4.6 Biological Resources Draft Environmental Impact Report SCH No. 2002091081 Prepared for: City of Santa Clarita Department of Planning & Building Services 23920 Valencia Boulevard, Suite 302 Santa Clarita, California 91355 Prepared by: Impact Sciences, Inc. 30343 Canwood Street, Suite 210 Agoura Hills, California 91301 March 2004 Revised Section 4.6 Biological Resources Draft Environmental Impact Report SCH No. 2002091081 Prepared for: City of Santa Clarita Department of Planning & Building Services 23920 Valencia Boulevard, Suite 302 Santa Clarita, California 91355 Prepared by: Impact Sciences, Inc. 30343 Canwood Street, Suite 210 Agoura Hills, California 91301 March 2004 Table of Contents Volume I: Environmental Impact Report Section Page Introduction....................................................................................................................I-1 Executive Summary ......................................................................................................ES-1 1.0 Project Description....................................................................................................... 1.0-1 2.0 Environmental and Regulatory Setting......................................................................... 2.0-1 3.0 Cumulative Impact Analysis Methodology .................................................................. 3.0-1 4.0 Environmental Impact Analyses................................................................................... 4.0-1 4.1 Geotechnical Hazards.......................................................................................... -

SMMC Annual Report Fiscal Year 2019-2020

SANTA MONICA MOUNTAINS CONSERVANCY ANNUAL REPORT FISCAL YEAR 2019-2020 PROJECT ACTIVITY AND COMPREHENSIVE PLAN CERTIFICATION State of California, Gavin Newsom, Governor The Natural Resources Agency, Wade Crowfoot, Secretary Dedicated to JEROME C. DANIEL Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy and Advisory Committee Member 1983-2020 CONTENTS Mission Statement ....................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy Members .................................................... 3 Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy Advisory Committee ................................. 4 Strategic Objectives ..................................................................................................... 7 Encumbering State Funds Certification-Interest Costs .......................................... 9 Workprogram Priorities ............................................................................................ 10 River/Urban ......................................................................... See attached map Simi Hills ............................................................................... See attached map Western Rim of the Valley .................................................. See attached map Eastern Rim of the Valley ................................................... See attached map Western Santa Monica Mountains ..................................... -

Notice of Intent, Notice of Preparation, Scoping Meeting Sign-In

United States Department of Defense, et al., "Notice of Intent, Notice of Preparation, Scoping Meeting Sign-In Sheet, Scoping Meeting Request to Speak/Written Comment Forms, Scoping Meeting Transcript, and Related Comment Letters" (August 2005) 41380 Federal Register/Vol. 70, No. 137/Tuesday, July 19, 2005/Notices including suggestions for reducing this DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: burden to the General Services Questions about the proposed action Administration, FAR Secretariat (VIR), Department of the Army; Corps of and Draft EIS/EIR can be answered by 1800 F Street, NW, Room 4035, Engineers Dr, Aaron O. Allen, Corps Project Washington, DC 20405. Manager, at (805) 585-2148. Comments Intent To Prepare a Draft shall be addressed to: U.S. Army Corps FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Environmental Impact Statement! of Engineers, Los Angeles District, Jeremy Olson, Contract Policy Division, Environmental Impact Report (DEIS! Ventura Field Office, ATTN: File GSA (202) 501-3221. DEIR) for Proposed Future Permit Number 2003-01264-AOA, 2151 Actions Under Section 404 of the Clean SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Alessandro Drive, Suite 110, Ventura, Water Act for the Newhall Ranch CA 93001. Alternatively, comments can A. Purpose Specific Plan and Associated Facilities be e-mailed to: Along Portions of the Santa Clara Aaron,O.AIlen@usace,army,mil. Advance payments may be authorized River and Its Side Drainages, and under Federal contracts and Development of a Candidate SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: subcontracts, Advance payments are the Conservation Agreement with 1, Project Site and Background least preferred method of contract Assurances (CCAA) for the San Information, The Newhall Ranch site is financing and require special Fernando Valley Spineflower, in Los located in northern Los Angeles County determinations by the agency head or Angeles County, California, With the and encompasses approximately 12,000 designee. -

County of Los Angeles Emergency Survival Guide

COUNTY OF LOS ANGELES EMERGENCY SURVIVAL GUIDE FGHIJK As a resident of one of the many unincorporated areas of Los Angeles County, you are an important LMNOPQ part of emergency planning and preparedness. Unincorporated areas are not part of any city and are RSTUVX governed by the five-member Board of Supervisors of the County of Los Angeles. The Board acts as your “city council” and is responsible for establishing YBCADW policies and regulations that affect you and your neighborhood. The Board also governs the County Zabcde Departments that provide services in your area including recreation, solid waste, planning, law enforcement, fghijk fire fighting, and social programs. The County is your first responder to disasters such as flood, fire, lmnopq earthquake, civil unrest, tsunami, and terrorist attacks. rstuvE This Guide will help you to better prepare for, respond to and recover from disasters that face Los Angeles GHIJKL County. Our goal is to provide tips that assist you to be self-sufficient after a disaster. In addition to this Guide, MNOPQR we recommend that you increase your awareness of emergency situations and the skills you need to prepare your family, neighbors and your community. Become STVWXY GUIDE SURVIVAL Community Emergency Response Team (CERT) qualified BACDEF GUIDE SURVIVAL and join a local CERT Disaster Response Team. CERT Teams strengthen the ability of our communities to FGHIJK quickly recover after major disasters. LMNOPQ This guide is a starting point. For more information on preparing for disasters, please visit the website RSTUVX for the County’s Emergency Survival Program (ESP) at www.espfocus.org or call the ESP Hotline YBCADW at (213) 974-1166 to receive free information on how Zabcde to be prepared for emergencies and disasters. -

Sand Canyon Ranch Estates | SANTA CLARITA the Robott Land Hoffman COMPANY Company 1 PROPERTY OVERVIEW

Rare Approved Tract Map for High-End Product in Supply Constrained Santa Clarita Market SAND CANYON 2 to 5.74 Acre Lot Sizes Surrounded by Luxury Semi-Custom Production & Custom Homes Adjacent Neighborhood Re-Sales from $1M to $3.4M RANCH ESTATES LOS ANGELES 22 Approved Large Luxury Estate Lots NEWHALL AVE City of Santa Clarita | Los Angeles County, CA SANTA CLARITA 14 D N R CANYO PLACERITA SA N ND C Example Home Nearby ANY ON RD INFORMATIONAL PACKAGE Erik Christianson, CA BRE #01475105 THE HOFFMAN COMPANY T 949.705.0920 | [email protected] The Southern California Office RoBott Land 18881 Von Karman Avenue, Suite 150 COMPANY Hoffman Steve Botthof, CA BRE #01131793 Irvine, CA 92612 T 310.299.7574 x 101 | [email protected] Company T 949.553.2020 | F 949.553.8449 www.robottland.com Larry Roth CA BRE #01473762 Land Brokers T 310.299.7574 x 102 | larry@ robottland.com www.hoffmanland.com Realty Advisors DISCLAIMER The information contained in this offering material (“Brochure”) is furnished solely for the purpose of a review by prospective purchaser of any portion of the subject property in the City of Santa Clarita, County of Los Angeles California (“Property”) and is not to be used for any other purpose or made available to any other person without the express written consent of Scheel Dallape Inc. d/b/a The Hoffman Company Organization (“The Hoffman Company”). The material is based in part upon information obtained by The Hoffman Company from sources it deems reasonably reliable. Summaries of any documents are not intended to be comprehensive or all inclusive but rath- er only an outline of some of the provisions contained therein. -

Caltrans Team — Page 2

Inter change News and updates from a coalition of community and business leaders focused on the health and vitality of California’s transportation backbone — Interstate 5 Volume 5, No. 1 Summer 2007 On the Road to Relief ALSO INSIDE Message from the Executive Director — Page 2 Profile: The Caltrans Team — Page 2 Coalition Launches New Website — Page 5 ‘Why I-5 Is Important to Me” — Page 6 North County Project Updates — Page 8 Message from the Chairman — Page 10 www.goldenstategateway.org Phone: 661.775.0455 Fax: 661.294.8188 25709 Rye Canyon Road, Caltrans launches a study that could pave the way Suite 105 Santa Clarita, CA 91355 for an extreme Interstate 5 makeover — Story, page 3 From the Caltrans Assigns Well-Qualified Executive Director Team to I-5 Study Turning Kosinski: Project goals Money Into include increased safety, congestion relief Mobility and environmental re - By Victor Lindenheim Executive Director, sponsibility. Golden State Gateway Coalition fter the passage of the infra - xperience. Attentiveness. Expertise. structure bond proposal Leadership. These are just some of (Proposition 1B) last year, a the qualifications possessed by the Asigh of collective relief could be ECaltrans team assigned to the Interstate 5 heard from California’s voters — es - HOV and Truck Lane Study, which is ex - pecially from those of us who live pected to pave the way for much-needed and work in Southern California, improvements to the I-5 corridor in north - Ronald Kosinski and know the chronic pain of free - ern Los Angeles County. way gridlock. Heading the Caltrans team is Ronald Today, there is Kosinski, Caltrans’ deputy district director transportation projects in the Los Angeles guarded opti - for Environmental Planning, who has pro - and Ventura region. -

Board Agenda and Report Packet

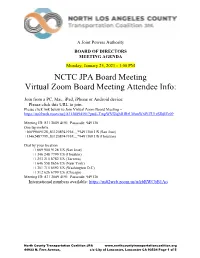

A Joint Powers Authority BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING AGENDA Monday, January 25, 2021 - 1:00 PM NCTC JPA Board Meeting Virtual Zoom Board Meeting Attendee Info: Join from a PC, Mac, iPad, iPhone or Android device: Please click this URL to join. Please click link below to Join Virtual Zoom Board Meeting – https://us02web.zoom.us/j/83120894191?pwd=TmpWVGlqMHRzU0hmWnlYZU1zSDdlZz09 Meeting ID: 831 2089 4191 Passcode: 949130 One tap mobile +16699009128,,83120894191#,,,,*949130# US (San Jose) +13462487799,,83120894191#,,,,*949130# US (Houston) Dial by your location +1 669 900 9128 US (San Jose) +1 346 248 7799 US (Houston) +1 253 215 8782 US (Tacoma) +1 646 558 8656 US (New York) +1 301 715 8592 US (Washington D.C) +1 312 626 6799 US (Chicago) Meeting ID: 831 2089 4191 Passcode: 949130 International numbers available: https://us02web.zoom.us/u/kbRWCbB1Ao North County Transportation Coalition JPA www.northcountytransportationcoalition.org 44933 N. Fern Avenue, c/o City of Lancaster, Lancaster CA 93534 Page 1 of 5 NCTC JPA BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD MEMBERS Chair, Supervisor Kathryn Barger, 5th Supervisorial District, County of Los Angeles Mark Pestrella, Director of Public Works, County of Los Angeles Victor Lindenheim, County of Los Angeles Austin Bishop, Council Member, City of Palmdale Laura Bettencourt, Council Member, City of Palmdale Bart Avery, City of Palmdale Marvin Crist, Vice Mayor, City of Lancaster Kenneth Mann, Council Member, City of Lancaster Jason Caudle, City Manager, City of Lancaster Marsha McLean, Council Member, City of Santa Clarita Robert Newman, Director of Public Works, City of Santa Clarita Vacant, City of Santa Clarita EX-OFFICIO BOARD MEMBERS Macy Neshati, Antelope Valley Transit Authority Adrian Aguilar, Santa Clarita Transit BOARD MEMBER ALTERNATES Dave Perry, County of Los Angeles Juan Carrillo, Council Member, City of Palmdale Mike Hennawy, City of Santa Clarita NCTC JPA STAFF Executive Director: Arthur V. -

The Heritage Junction Dispatch a Publication of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society

The Heritage Junction Dispatch A Publication of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society Volume 36, Issue 4 July August 2010 Calendar President’s Message by Alan Pollack Monday, July 26 idden beneath the “Big Four” entrepreneurs of the Central the Interstate Pacific Railroad (Crocker, Leland Stanford, Board of Directors Meeting H 6:30 PM Saugus Station 5-Highway 14 Mark Hopkins, and Collis Huntington) set Saturday, August 1 interchange in the their sights on connecting Northern and Newhall Pass lies Southern California via the Southern Pacific Deadline for the March-April Dispatch a tunnel portal, Railroad. They began buying out smaller one of the great railroads in California, including the San Monday, August 23 historic treasures Francisco and San Jose Railroad, run by the Board of Directors Meeting of Los Angeles. On future founder of Newhall, California, Henry 6:30 PM Saugus Station September 5, 1876, Mayo Newhall. The railroad builders decided Charles Crocker on a route stretching from San Francisco drove in a golden spike at Lang Station in south through California’s Central Valley, Soledad Canyon to celebrate the completion then penetrating the Tehachapi mountains Check www.scvhistory.org for of the Southern Pacific Railroad in California. through the Tehachapi Pass (in which they other upcoming events. This monumental day would not have been built the famous Tehachapi Loop), then possible were it not for the completion of south through the Mojave Desert passing the San Fernando Railroad Tunnel by a crew through what are now the town of Mojave of about 1000 Chinese workers (and 500 and the cities of Lancaster and Palmdale, others) in the summer of 1876. -

18289-18323 Sierra Hwy Santa Clarita, Ca 91387

FEB TO SEPT 2021 6 Mos. No Mortgage Pmt on SBA Loans OFFERING MEMORANDUM | LISTING PRICE: $3,900,000 18289-18323 SIERRA HWY SANTA CLARITA, CA 91387 OWNER-USER MEDICAL OFFICE CONVERSION OPPORTUNITY This Memorandum (“Offering Memorandum”) has been prepared by Hudson Commercial Partners, Inc. based on information that was furnished to us by sources we deem to be reliable. No warranty or representation is made to the accuracy thereof; subject to correction of errors, omissions, change of price, prior sale, or withdrawal from market without notice. This Memorandum is being delivered to a limited number of parties who may be interested in and capable of purchasing the Property. By its acceptance hereof, each recipient agrees that it will not copy, reproduce or distribute to others this Memorandum in whole or in part, at any time, without the prior written consent of Hudson Commercial Partners, Inc., and it will keep permanently confidential all information contained herein not already public and will use this Confidential Memorandum only for the purpose of evaluating the possible acquisition of the Property. This Memorandum does not purport to provide a complete or fully accurate summary of the Property or any of the documents related thereto, nor does it purport to be all-inclusive or to contain all of the information, which prospective buyers may need, or desire. All financial projections are based on assumptions relating to the general economy, competition and other factors beyond the control of the Owner and, therefore, are subject to material variation. This Memorandum does not constitute an indication that there has been no change in the business or affairs of the Property or the Owner since the date of preparation of this Memorandum. -

Plan Santa Clarita 2020 Newsletter 2015

Santa Clarita Public Safety Building and Creating Community Enhancing Economic Vitality Community Beautication Sustaining Public Infrastructure Proactive, Transparent and Responsive Government Services The City will keep Santa Clarita as one of the nation’s safest communities by providing high The City will build vital infrastructure and provide services and programs that enrich a growing The City will strengthen and grow the Santa Clarita economy by fostering economic The City will create and maintain an aesthetically and visually pleasing community, which The City will maintain the safety, quality and value of our public infrastructure, which will be The City will provide the highest quality municipal services consistent with the values in our City To Our Valuable City Employees: quality public safety services and facilities and preserving the integrity of neighborhoods, and diverse community, which will be accomplished in the following ways: development, lm and tourism, and provide business friendly services that result in quality will be accomplished in the following ways: accomplished in the following ways: Philosophy Statement, which will be accomplished in the following ways: Vision, anticipation and prioritization are essential elements in preparing for a successful which will be accomplished in the following ways: jobs, increased retail activity and the attraction of new investments, which will be 1. Work with the Senior Center to support the construction of the new Santa Clarita Valley Senior Center. Vision, anticipation and prioritization are essential elements in preparing for a successful future and to future and to ensure the City of Santa Clarita continues to provide superior municipal accomplished in the following ways: 1. -

WSCP Public Workshop Jan 28 2021 Summary

Water Shortage Contingency Plan Public Workshop January 28, 2021 SUMMARY Contents 1. Background ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Objectives ...................................................................................................................................................................... 1 3. When and Where........................................................................................................................................................ 1 4. Notifications and Outreach .................................................................................................................................... 2 5. Public Workshop ......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Workshop Format ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 Community Input ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 6. Online Input Form ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Appendix A. Presentation Slides B. Workshop Outreach 1. Background Santa Clarita Valley -

City of Santa Clarita General Plan Circulation

City of Santa Clarita General Plan Circulation CIRCULATION ELEMENT June, 2011 PART 1: BACKGROUND AND CIRCULATION ISSUES A. Purpose and Intent of the Circulation Element The Santa Clarita Valley’s circulation system provides vital connections linking neighborhoods, services, and employment centers throughout the community and the region. A comprehensive transportation network of roadways, multi-use trails and bike paths, bus transit, and commuter rail provides mobility options to Valley residents and businesses. Planning for the ultimate location and capacity of circulation improvements will also enhance economic strength and quality of life in the Valley. The Circulation Element plans for the continued development of efficient, cost-effective and comprehensive transportation systems that are consistent with regional plans, local needs, and the Valley’s community character. The Circulation Element complements and supports the Land Use Element, insofar as a cohesive land use pattern cannot be achieved without adequate circulation. The Circulation Element identifies and promotes a variety of techniques for improving mobility that go beyond planning for construction of new streets and highways. These techniques include: development of alternative travel modes and support facilities; increased efficiency and capacity of existing systems through management strategies; and coordination of land use planning with transportation planning by promoting concentrated, mixed-use development near transit facilities. B. Background The California Government Code describes conditions and data that must be researched, analyzed, and discussed in a Circulation Element. Section 65302(b) states that the general plan shall include the general location and extent of existing and proposed major thoroughfares, transportation routes, terminals and other local public utilities and facilities.