Diagnostic Survey of Mental and Substance Use Disorders in HUNT (Psykhunt)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Møteinnkalling Overhalla Formannskap

Møteinnkalling Utvalg: Overhalla formannskap Møtested: Kommunestyresalen, Adm.bygg Dato: 05.11.2019 Tidspunkt: 12:00 De faste medlemmene innkalles med dette til møtet. Den som har gyldig forfall, eller ønsker sin habilitet i enkeltsaker vurdert, melder dette så snart som mulig på e-post: [email protected]. Ved melding om forfall: Begrunnelse for forfall skal oppgis. Varamedlemmer møter etter nærmere innkalling. Per Olav Tyldum Ordfører Torunn Grønnesby Formannskapssekretær 1 Sakliste Saksnr Innhold PS 64/19 Søknad om permisjon fra verv som varamedlem til Overhalla kommunestyre - Marianne Øyesvold PS 65/19 Innspill - Egnet plassering av hurtigladepunkt i Overhalla PS 66/19 Søknad om sluttfinansiering av nytt orgel i Ranem kirke PS 67/19 Deltakelse i IKA Trøndelag IKS PS 68/19 Tilstands- og utviklingsrapport for de kommunale grunnskolene 2019. PS 69/19 Navnesak Overhalla kommune - Boligveg ved Skiljåsaunet PS 70/19 Søknad om kjøp av tilleggsareal til Svalifoten 5, eier Robert Gabrielsen og Monica Hanssen PS 71/19 Brøndbo Holding AS - Søknad om kjøp av tilleggstomt på Skage industriområde PS 72/19 Søknad om dispensasjon fra kommuneplanens arealdel og fradeling av gårdstunet på Åsheim, 1/2, eier Lars Iver Kalnes PS 73/19 Søknad om dispensasjon og fradeling av bebygd tun, Elverum, 75/5, eier Jan Olav Tømmerås PS 74/19 Søknad om dispensasjon, fradeling og makebytte mellom 12/14-Pål Tore Raabakken og 11/3 - Rune Hansen PS 75/19 Regnskaps- og virksomhetsrapport 2. tertial 2019 PS 76/19 Valg av nytt kommunestyremedlem til prosjektgruppa -

The DEER-WOOD Project North-Trøndelag County, Norway

The DEER-WOOD project North-Trøndelag county, Norway Skogeierforeninga Nord (Forest Owners’ Association, North) 1. Background – Nordic/ Scottish Collaboration. In February 1998, Inn-Trøndelag Forest Owners’ Association (I-T FOA, later merged into Forest Owners’ Association North) was asked by the Norwegian Forest Owners’ Federation (NFOF) to participate in a project on Managing deers across multiple land ownerships. The background for the question was: 1) that NFOF had taken the responsibility on behalf of Nordic Council of Ministers to establish cooperation between Scottish and Nordic units in forestry, 2) that an initiative had recently been made by Forestry Commission, Edinburgh, on a collaboration on deer management, 3) that an NPP-funding system had been established. Statistics of elk culled in Nord-Trøndelag county (N-T) show that around 1960 1500 elks were culled annually, 1970 600, since then an even growth so for the recent years the annual number culled has reached 4000 or more. In 1997 the venison value amounted to NOK mio 37, while the road side value of timber harvested was NOK mio 184 (average for the 90-es NOK mio 230). Since early 80-es N-T has had the following aim for deer management: ”The deer management should be practiced in order to obtain the highest possible level of production and of venison. At the same time eventual damage on agriculture, horticulture, forestry and traffic should be kept on an acceptable level. There is a general agreement that the management has been successful regarding raising the number of moose and their productivity. The number now is on a historically speaking high level. -

Beredskapsanalyse Vannforsyning

Overhalla kommune - positiv, frisk og framsynt BEREDSKAPSANALYSE VANNFORSYNING DEL 3. ANLEGGSBESKRIVELSE, PRODUKSJON OG DISTRIBUSJON Martin Lysberg 06.01.2017 Overhalla kommune - positiv, frisk og framsynt Innhold 0. SAMMENDRAG 3 1. ANLEGGSBESKRIVELSE FOR PRODUKSJON OG DISTRIBUSJON 3 2. DRIFT DE SISTE 10 ÅR 7 3. TILTAK 10 4. EKSEMPEL PÅ VANNLEDNINGSBRUDD 12 BEREDSKAP VANNFORSYNING DEL 3 - OVERHALLA KOMMUNE 2 Overhalla kommune - positiv, frisk og framsynt 0. SAMMENDRAG At samfunnet ikke er godt nok rustet til å håndtere en vanskelig situasjon på en tilfredsstillende måte, kan ofte føre til alvorlige ulykker og svikt i samfunnsviktige systemer. Dette kan resultere i vesentlige tap både for enkeltmennesker, bedrifter og miljøet omkring oss. Som oftest er det bare enkle midler som skulle til for å hindre slike uønskede hendelser. Derfor er første skritt å danne seg et bilde over de hendelser som kan skje, samt risikoen for at situasjoner kan oppstå. I 2016 ble det gjennomført en revisjon fra Mattilsynet. I etterkant av denne ble det varslet om vedtak på noen punkter. Revisjonen ble vurdert og opp imot dagens status, og derav ses behovet for en bedre oversikt. I dette dokumentet vil følgende tema belyses: Anleggsbeskrivelse for produksjon og distribusjon konovatnet fellesvannverk. Utstyrsliste for materiell tilgjengelig i beredskapen for vannverket. Øvelsesplan for vannverket Sjekklister for aktuelle hendelser. 1 . ANLEGGSBESKRIVELSE FOR PRODUKSJON OG DISTRIBUSJON. 1.1. Systembeskrivelse 1.1.1. Generelt Denne rapporten beskriver: 1. Konovatnet fellesvannverk Vanninntak i Konovatnet, overføringsledning til Rakdalåsen renseanlegg, og Rakdalåsen renseanlegg. Ledningsnett, høydebasseng på Ryggahøgda og noen små trykkøkningsanlegg fordelt på ledningsnettet. Konovatnet fellesvannverk er interkommunalt for Overhalla og Grong kommune. -

Nye Fylkes- Og Kommunenummer - Trøndelag Fylke Stortinget Vedtok 8

Ifølge liste Deres ref Vår ref Dato 15/782-50 30.09.2016 Nye fylkes- og kommunenummer - Trøndelag fylke Stortinget vedtok 8. juni 2016 sammenslåing av Nord-Trøndelag fylke og Sør-Trøndelag fylke til Trøndelag fylke fra 1. januar 2018. Vedtaket ble fattet ved behandling av Prop. 130 LS (2015-2016) om sammenslåing av Nord-Trøndelag og Sør-Trøndelag fylker til Trøndelag fylke og endring i lov om forandring av rikets inddelingsnavn, jf. Innst. 360 S (2015-2016). Sammenslåing av fylker gjør det nødvendig å endre kommunenummer i det nye fylket, da de to første sifrene i et kommunenummer viser til fylke. Statistisk sentralbyrå (SSB) har foreslått nytt fylkesnummer for Trøndelag og nye kommunenummer for kommunene i Trøndelag som følge av fylkessammenslåingen. SSB ble bedt om å legge opp til en trygg og fremtidsrettet organisering av fylkesnummer og kommunenummer, samt å se hen til det pågående arbeidet med å legge til rette for om lag ti regioner. I dag ble det i statsråd fastsatt forskrift om nærmere regler ved sammenslåing av Nord- Trøndelag fylke og Sør-Trøndelag fylke til Trøndelag fylke. Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet fastsetter samtidig at Trøndelag fylke får fylkesnummer 50. Det er tidligere vedtatt sammenslåing av Rissa og Leksvik kommuner til Indre Fosen fra 1. januar 2018. Departementet fastsetter i tråd med forslag fra SSB at Indre Fosen får kommunenummer 5054. For de øvrige kommunene i nye Trøndelag fastslår departementet, i tråd med forslaget fra SSB, følgende nye kommunenummer: Postadresse Kontoradresse Telefon* Kommunalavdelingen Saksbehandler Postboks 8112 Dep Akersg. 59 22 24 90 90 Stein Ove Pettersen NO-0032 Oslo Org no. -

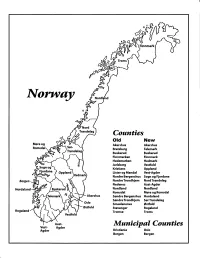

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Poststeder Nord-Trøndelag Listet Alfabetisk Med Henvisning Til Kommune

POSTSTEDER NORD-TRØNDELAG LISTET ALFABETISK MED HENVISNING TIL KOMMUNE Aabogen i Foldereid ......................... Nærøy Einviken ..................................... Flatanger Aadalen i Forradalen ...................... Stjørdal Ekne .......................................... Levanger Aarfor ............................................ Nærøy Elda ........................................ Namdalseid Aasen ........................................ Levanger Elden ...................................... Namdalseid Aasenfjorden .............................. Levanger Elnan ......................................... Steinkjer Abelvær ......................................... Nærøy Elnes .............................................. Verdal Agle ................................................ Snåsa Elvalandet .................................... Namsos Alhusstrand .................................. Namsos Elvarli .......................................... Stjørdal Alstadhoug i Schognen ................. Levanger Elverlien ....................................... Stjørdal Alstadhoug ................................. Levanger Faksdal ......................................... Fosnes Appelvær........................................ Nærøy Feltpostkontor no. III ........................ Vikna Asp ............................................. Steinkjer Feltpostkontor no. III ................... Levanger Asphaugen .................................. Steinkjer Finnanger ..................................... Namsos Aunet i Leksvik .............................. -

Administrative and Statistical Areas English Version – SOSI Standard 4.0

Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 Administrative and statistical areas Norwegian Mapping Authority [email protected] Norwegian Mapping Authority June 2009 Page 1 of 191 Administrative and statistical areas English version – SOSI standard 4.0 1 Applications schema ......................................................................................................................7 1.1 Administrative units subclassification ....................................................................................7 1.1 Description ...................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 CityDistrict ................................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 CityDistrictBoundary ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.3 SubArea ................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.4 BasicDistrictUnit ....................................................................................................... 15 1.1.5 SchoolDistrict ........................................................................................................... 16 1.1.6 <<DataType>> SchoolDistrictId ............................................................................... 17 1.1.7 SchoolDistrictBoundary ........................................................................................... -

Statsbudsjettet 2020 Trøndelag 8

Statsbudsjettet 2020 Trøndelag 8. oktober 2019 Kommualdirektør Mari Mogstad 08.10.2019 Programmet for dagen TID Innhold 10.00 Velkommen ved kommunaldirektør Mari Mogstad, FMTL Kommunedialog mv v/ Trude Mathisen, FMTL Fordeling skjønnsmidler 2019 og 2020, Sigrid Hynne, FMTL 10.35 – 10.45 Pause 10.45 – 11.15 Innlegg fra Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet, statssekretær Lars Jacob Hiim 11.15 – 11.45 Innlegg fra KS, områdedirektør Interessepolitikk Helge Eide 11.45 – 12.00 Spørsmål og kommentarer til KMD og KS 12.00 – 12.25 Pause 12.25 – 12.40 Fylkesoversikt Trøndelag – tiltak i statsbudsjettet 2019 v/ Ole Tronstad, Trøndelag Fylkeskommune 12.40 – 13.00 Virkning for kommunene i Trøndelag, v/ Stule Lund, FMTL 13.50 – 14.00 Avslutning ved Fylkesstyreleder Marit Voll, KS E-post adresse for spørsmål: [email protected] Nye kommuner og ny kommunedialog Statsbudsjettkonferansen 2019 8. oktober 2019 08.10.2019 Nye kommuner • 19 kommuner blir til 9 nye kommuner fra 1.1.2020 • + Indre Fosen ny kommune fra 1.1. 2018 • 65 % av innbyggerne i fylket vil bo i en ny kommune • Kommunene har mottatt 626 mill. kr i engangstilskudd, reformstøtte, infrastrukturtilskudd, regionsentertilskudd, og overgangsordninger • Inndelingstilskuddet vil gi full kompensasjon for tap av basistilskudd og netto nedgang i distriktstilskudd som følge av sammenslåingen (15 + 5 år) • Ved utilsiktede virkninger i inntektssystemet vil det bli vurdert kompensasjon ifht. skjønnsmidler 08.10.2 019 Kommunedialogen • Nytt og større fylke. Store avstander • Felles tenkning -

Protokoll Namdalstinget 04.11.19

Møteprotokoll Utvalg: Namdalstinget Møtested: Norveg, Rørvik Dato: 04.11.2019 Tidspunkt: Fra 10:00 til 14:30 Faste medlemmer som møtte: Navn Funksjon Representerer Olav Jørgen Bjørkås Flatanger Lars Haagensen Flatanger Turid Kjendlie Flatanger Borgny Grande Grong Erlend Fiskum Grong Audun Fiskum Grong Linda Renate Linmo Grong Oddny Lysberg Grong Hege Nordheim-Viken Høylandet Jo Arne Kjøglum Høylandet Sverre Lilleberrre Høylandet Rita Rosendal Høylandet Rune Kristian Grongstad Høylandet Mona Hellesø Høylandet Tommy Tørring Høylandet Elisabeth Helmersen Leka Mari-Anne Hoff Leka Steinar Tørriseng Leka Per Helge Johansen Leka Arnhild Holstad Namsos Kjersti Tommelstad Namsos Gina Holmen Berre Namsos Grete Lervik Namsos Bjørn Helmersen Namsos Baard S. Kristiansen Namsos Anette Liseter Namsos Steinar Lyngstad Namsos Sissel Stormo Holtan Namsos Amund Lein Namsos Stian Brekkvassmo Namsskogan Borgund Torseth Namsskogan Heidi Brekkvassmo Namsskogan Elisabeth Bjørhusdal Namsskogan Amund Hellesø Nærøysund Mildrid Finnehaug Nærøysund Ingunn L. Lysø Nærøysund Terje Settenøy Nærøysund Espen Lauritzen Nærøysund Anette Laugen Nærøysund Marit Dille Nærøysund Tordis Fjær Solbakk Nærøysund John Einar Høvik Osen Egil Arve Johannessen Osen May-Britt Strand Ness Osen Håvard Strand Osen Line Stein Osen Johan Tetlien Sellæg Overhalla Hege Kristin Kværnø Saugen Overhalla Siv Åse Strømhylden Overhalla Jo Morten Aunet Overhalla Kai Terje Dretvik Overhalla May Storøy Overhalla Hans Oskar Devik Røyrvik Bodil Haukø Røyrvik Bertil Jønsson Røyrvik Hilde Staldvik Røyrvik -

Velkommen Til Frøya Og Hitra

Velkommen til Frøya og Hitra Fakta – Frøya og Hitra • Frøya – den fremste øya • Hitra • 76 meter over havet • Befolkning: 5 088 (1.kv 2020) • 5400 små og store øyer, holmer og skjær • 231 km2 landareal • Pendling – ut: 429, inn: 516 • 2255 km kystlinje (2,7 % av Norges • 2 260 eneboliger kystlinje) • 1 927 fritidsboliger • Befolkning: 5 166 (1.kv 2020) • Pendling – ut: 390, inn: 660 • 1 990 eneboliger • 1 070 fritidsboliger Befolkningsutvikling Sysselsetting Prosentvis endring i antall sysselsatte 4.kvartal 2008 til 4. kvartal 2018 Utvikling i befolkning og sysselsetting i kommunene i Trøndelag 40,0 % Vekst befolkning Vekst befolkning Nedgang arbeidsplasser Vekst arbeidsplasser 30,0 % Skaun Frøya 20,0 % Stjørdal Trondheim Malvik Melhus Hitra Vikna Levanger Orkdal 2019 (prosent) 2019(prosent) 10,0 % Klæbu Bjugn - Steinkjer Overhalla Verdal Ørland Frosta Midtre Gauldal Oppdal Namsos Åfjord Selbu Nærøy Inderøy Røros Grong Hemne Snillfjord Meldal 0,0 % Indre Fosen Agdenes Holtålen Høylandet Meråker Leka Rindal Flatanger Røyrvik Snåsa Roan Lierne Rennebu Namsskogan Osen Tydal Namdalseid -10,0 % Fosnes Endring Endring befolkning 2009 Verran -20,0 % Nedgang befolkning Nedgang befolkning Nedgang arbeidsplasser Vekst arbeidsplasser -30,0 % -20,0 % -10,0 % 0,0 % 10,0 % 20,0 % 30,0 % Endring sysselsetting 4.kvartal 2008-4. kvartal 2018 (prosent) Næringsliv • Hitra og Frøya står for: • ca. 51 % av eksporten av fisk fra Trøndelag • ca. 33 % av vareeksporten fra Trøndelag • ca. 18 % av den totale eksporten fra Trøndelag Helhetlig ROS • Risikokatalysatorer En risikokatalysator er en hendelse som kan påvirke en annen hendelse (som inntreffer samtidig) slik at konsekvensene av denne forsterkes. (..) Parallelle hendelser vil derfor kunne påvirke beredskapsevnen til kommunen opp mot kapasitet på ressursene. -

Møteinnkalling

Møteinnkalling Utvalg: Fellesnemnda Indre Fosen kommune Møtested: Leksvik kommunehus, kommunestyresalen Møtedato: 27.10.2016 Tid: 12:00 Forfall meldes til Servicekontorene i kommunene som sørger for innkalling av varamedlemmer. Varamedlemmer møter kun ved spesiell innkalling. Innkalling er sendt til: Navn Funksjon Representerer Steinar Saghaug Leder LE-H Bjørnar Buhaug Medlem LE-SP Ove Vollan Ordfører RI-HØ Camilla Sollie Finsmyr Medlem LE-SP Liv Darell Medlem RI-SP Linda Renate Lutdal Medlem LE-H Bjørn Vangen Medlem RI-HØ Maria Husby Gjølgali Medlem RI-AP Per Kristian Skjærvik Medlem RI-AP Knut Ola Vang Medlem LE-AP Merethe Kopreitan Dahl Medlem LE-AP Rannveig Skansen Medlem LE-SV Line Marie Rosvold Abel Medlem LE-V Tormod Overland Medlem RI-FRP Reidar Gullesen Medlem RI-V Harald Fagervold Medlem RI-PP Jon Normann Tviberg Medlem LE-KRF Vegard Heide Medlem RI-MDG Kurt Håvard Myrabakk Medlem LE-FRP Per Brovold Medlem RI-SV Odd - Arne Sakseid Medlem RI-KRF Drøftingssaker: - Politisk organisering i 2017 - Hvordan bør Fosen Helse IKS utvikles? Strategiprosess. Innledning v/ daglig leder Leena Stenkløv Orienteringssaker: - Ansettelse ledergruppe v/ prosjektleder Vigdis Bolås - Primærsykehus, mulige samarbeidsformer v/ Bjørn Ståle Aalberg og Hilde Anhanger Karlsen - IKT i Indre Fosen kommune v/ Bjørn Ståle Aalberg og Robert Karlsen - Rapportering prosjektbudsjett v/ prosjektleder Vigdis Bolås - Rapportering arbeidsgruppene v/ ledere politiske arbeidsgrupper og prosjektleder -1- Info prosjektleder Info leder og nestleder i fellesnemnda Steinar -

The Effects of SND's Financial Support for Businesses

THE EFFECTS OF SND’s FINANCIAL SUPPORT FOR BUSINESSES Follow-up study in 2004 of companies which received SND financing in 2000 by Einar Lier Madsen Bjørn Brastad NF Report No. 3/2005 ISBN: 82-7321-522-9 ISSN: 0805-4460 N-8049 BODØ, Norway Tel.: 75 51 76 00 Telefax: 75 51 72 34 REFERENCE PAGE - This report may also be ordered by e-mail from [email protected] Title Publicly accessible: NF Report No.: The effects of SND’s financial support for Yes 3/2005 businesses ISBN ISSN Follow-up study in 2004 of companies which 82-7321-522-9 0805-4460 received SND financing in 2000 Number of pages Date: and attachments: 181 August 2004 Authors Project Manager (signature): Einar Lier Madsen Einar Lier Madsen Bjørn Brastad Research Manager: Elisabet Ljunggren Project Client 70 01 07 Follow-up Study 2004 The Norwegian Ministry of Trade and Industry, the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development, the Ministry of Fisheries, the Ministry of Agriculture and Food and Innovation Norway (formerly The Norwegian Industrial and Regional Development Fund (SND)) Client’s Representative Lars Hagen/Gry E. Monsen Summary This document presents a follow-up UKey wordsU study of the participants in the preliminary study in 2001 (the 2000 group) and is based on Regional policy interviews carried out in 2004 with 807 Innovation Norway (the Norwegian Industrial and companies of various types and in various Regional Development Fund (SND)) industries throughout Norway. The main Financial support for businesses emphasis of the follow-up study is on clarifying the following