Transfers in Contemplation of Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief Description of Federal Taxes

A BRIEF DESCRIFTION OF FEDERAL TAXES ON CORPORATIONS SINCE i86i WMUAu A. SU. ND* The cost to the federal government of financing the Civil War created a need for increased revenue, and Congress in seeking new sources tapped theretofore un- touched corporate and individual profits. The Act of July x, x862, amending the Act of August 5, x86i, is the first law under which any federal income tax was collected and is considered to be largely the basis of our present system of income taxation. The tax acts of the Civil War period contained provisions imposing graduated taxes upon the gain, profits, or income of every person2 and providing that corporate profits, whether divided or not, should be taxed to the stockholders. Certain specified corporations, such as banks, insurance companies and transportation companies, were taxed at the rate of 5%, and their stockholders were not required to include in income their pro rata share of the profits. There were several tax acts during and following the War, but a description of the Act of 1864 will serve to show the general extent of the coiporate taxes of that period. The tax or "duty" was imposed upon all persons at the rate of 5% of the amount of gains, profits and income in excess of $6oo and not in excess of $5,000, 7Y2/ of the amount in excess of $5,ooo and not in excess of -$o,ooo, and io% of the amount in excess of $Sxooo.O This tax was continued through the year x87i, but in the last two years of its existence was reduced to 2/l% upon all income. -

Ways and Means Committee's Request for the Former President's

(Slip Opinion) Ways and Means Committee’s Request for the Former President’s Tax Returns and Related Tax Information Pursuant to 26 U.S.C. § 6103(f )(1) Section 6103(f )(1) of title 26, U.S. Code, vests the congressional tax committees with a broad right to receive tax information from the Department of the Treasury. It embod- ies a long-standing judgment of the political branches that the tax committees are uniquely suited to receive such information. The committees, however, cannot compel the Executive Branch to disclose such information without satisfying the constitutional requirement that the information could serve a legitimate legislative purpose. In assessing whether requested information could serve a legitimate legislative purpose, the Executive Branch must give due weight to Congress’s status as a co-equal branch of government. Like courts, therefore, Executive Branch officials must apply a pre- sumption that Legislative Branch officials act in good faith and in furtherance of legit- imate objectives. When one of the congressional tax committees requests tax information pursuant to section 6103(f )(1), and has invoked facially valid reasons for its request, the Executive Branch should conclude that the request lacks a legitimate legislative purpose only in exceptional circumstances. The Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee has invoked sufficient reasons for requesting the former President’s tax information. Under section 6103(f )(1), Treasury must furnish the information to the Committee. July 30, 2021 MEMORANDUM OPINION FOR THE ACTING GENERAL COUNSEL DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY The Internal Revenue Code requires the Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) and the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) to keep tax returns and related information confidential, 26 U.S.C. -

Federal Income Tax Returns--Confidentiality Vs

Federal Income Tax Returns--Confidentiality vs. Public Disclosure* by Boris I. Bittker* * I. INTRODUCTION This article will examine the relationship between the individual's interest in privacy, reflected in such recent statutes as the Privacy Act of 1974, I and the public's right to know, which underlies legislation like the Freedom of Information Act. 2 The subject is of intrinsic impor tance, but it is particularly appropriate for an article in this lecture se ries, since privacy3 and disclosure4 were values of special interest to Justice Douglas. Neither the individual's right to privacy5 nor the pub lic's right to know6 is explicitly protected by the Constitution, but both do have constitutional overtones, and both are protected by various statutory provisions. Using federal income tax returns as the centerpiece of the discus sion, I propose to show how privacy and disclosure can come into con flict-a possibility that has been insufficiently recognized by the courts and the commentators. The leading treatise on political and civil rights,7 for example, treats the two subjects in separate chapters with virtually no acknowledgement that they are related, let alone that they • Copyright 1981 by Boris I. Bittker. •• Sterling Professor of Law. Yale University. This article is the modified text of a speech delivered at the Fifth Annual William O. Douglas Lecture Series. October 30. 1980. I. Pub. L. No. 93-579, § 3, 88 Stat. 1897 (amended 1975 & 1977) codified at 5 U.S.C § 552a (1976». 2. Pub. L. No. 89-554, 80 Stat. 383 (1966) (amended 1967, 1974, 1976 & 1978) (codified at 5 U.S.C § 552 (1976». -

RESTORING the LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E

COPYRIGHT © 2017 VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW ASSOCIATION RESTORING THE LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E. Hickman* & Gerald Kerska† Should Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents be eligible for pre-enforcement judicial review? The D.C. Circuit’s 2015 decision in Florida Bankers Ass’n v. U.S. Department of the Treasury puts its interpretation of the Anti-Injunction Act at odds with both general administrative law norms in favor of pre-enforcement review of final agency action and also the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the nearly identical Tax Injunction Act. A 2017 federal district court decision in Chamber of Commerce v. IRS, appealable to the Fifth Circuit, interprets the Anti-Injunction Act differently and could lead to a circuit split regarding pre-enforcement judicial review of Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents. Other cases interpreting the Anti-Injunction Act more generally are fragmented and inconsistent. In an effort to gain greater understanding of the Anti-Injunction Act and its role in tax administration, this Article looks back to the Anti- Injunction Act’s origin in 1867 as part of Civil War–era revenue legislation and the evolution of both tax administrative practices and Anti-Injunction Act jurisprudence since that time. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1684 I. A JURISPRUDENTIAL MESS, AND WHY IT MATTERS ...................... 1688 A. Exploring the Doctrinal Tensions.......................................... 1690 1. Confused Anti-Injunction Act Jurisprudence .................. 1691 2. The Administrative Procedure Act’s Presumption of Reviewability ................................................................... 1704 3. The Tax Injunction Act .................................................... 1707 B. Why the Conflict Matters ....................................................... 1712 * Distinguished McKnight University Professor and Harlan Albert Rogers Professor in Law, University of Minnesota Law School. -

Federal Register

> 11TTTO& ' FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 3 \ 1934 NUMBER 141 i/AHTED^ W a sh in gton , T h u rsd a y, J u ly 21, 1938 Rules, Regulations, Orders his hand and caused the seal of the De CONTENTS partment of Agriculture to be affixed in the city of Washington, District of Co RULES, REGULATIONS, ORDERS TITLE 7—AGRICULTURE lumbia, this 19th day of July, 1938. T itle 7—A griculture: [ seal! M. L. W ilson, Agricultural Adjustment Ad AGRICULTURAL ADJUSTMENT Acting Secretary of Agriculture. ADMINISTRATION ministration: Page [F. R. Doc. 38-2079; Filed, July 20,1938; Fresh prunes grown in Uma P roclamation W ith Respect to B ase 9:32 a. m.] tilla County, Oreg., Walla P eriod to be U sed for P urpose of Walla and Columbia M arketing A greement and O rder Counties, Wash.: R egulating H andling of F resh P runes Base period for marketing G rown in U matilla County in State Order R egulating the H andling in In agreement and order__1779 of Oregon, and W alla W alla and terstate and Foreign Commerce, and Order regulating handling Columbia Counties in State of W ash Such H andling as D irectly Burdens, in interstate, etc., com ington Obstructs or Affects I nterstate or F oreign Commerce of Fresh P runes merce_________________ 1779 By virtue of the authority vested in G rown in U matilla County in State Mainland cane sugar area the Secretary of Agriculture by the terms of Oregon and W alla W alla and Co ferais, determination of and provisions of Public Act No. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................... ix Introductory Notes to Tables ................................................................. xi Chapter A: Selected Economic Statistics ............................................... 1 A1. Resident Population of the United States ............................................................................3 A2. Resident Population by State ..............................................................................................4 A3. Number of Households in the United States .......................................................................6 A4. Total Population by Age Group............................................................................................7 A5. Total Population by Age Group, Percentages .......................................................................8 A6. Civilian Labor Force by Employment Status .......................................................................9 A7. Gross Domestic Product, Net National Product, and National Income ...................................................................................................10 A8. Gross Domestic Product by Component ..........................................................................11 A9. State Gross Domestic Product...........................................................................................12 A10. Selected Economic Measures, Rates of Change...............................................................14 -

The Revenue Act of 1924: Publicity, Tax Cuts, Response

The Revenue Act of 1924: Publicity, Tax Cuts, Response Daniel Marcin∗ March 25, 2014 Abstract The elasticity of taxable income (ETI) with respect to the marginal net-of-tax rate is an estimate of the aggregate response to tax rate changes. It is estimated without attributing cause to avoidance, evasion, or changes in economic growth. Historical ETI estimates in the public nance literature often rely on assumptions about income dynamics. A provision in the Revenue Act of 1924 for publicity of income tax returns allowed major newspapers to run lists of names, addresses, and tax payments in their pages. From these records, I constructed a dataset of very high income taxpayers. Over 10,000 individuals can be easily matched between the two years. In addition, the Revenue Act of 1924 sharply cut marginal tax rates. These changes can be used to estimate the ETI without distribution or rank preservation assumptions. Preliminary estimates indicate a positive ETI around 0.3 to 0.6, consistent with previous research. ∗Acknowledgements: Paul Rhode, David Albouy, Martha Bailey, and Josh Hausman for serving on my committee, seminar participants at Michigan, the Midwest Economics Association, the Economics and Busi- ness History Society, the World Cliometric Congress, and Nic Duquette for various helpful comments. Fund- ing: SRA, OTPR, Rackham, EHA, MITRE 1 I wish it to be understood that I have not the slightest prejudice against multi-millionaires. I like them. But I always feel this way when I meet one of them: You have made millionsgood; that means you have something in you. I wish you would show it. -

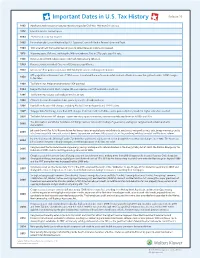

Important Dates in U.S. Tax History Release 16

Release 16 Important Dates in U.S. Tax History 1862 Abraham Lincoln enacts emergency measure to pay for Civil War: Minimum 3% tax rate. 1872 Lincoln’s income tax law lapses. 1894 2% federal income tax enacted. 1895 Income tax ruled unconstitutional by U.S. Supreme Court in Pollack v. Farmer’s Loan and Trust. 1909 16th amendment that authorizes Congress to collect taxes on income is proposed. 1913 Wyoming casts 37th vote, ratifying the 16th amendment. One in 271 people pays 1% rate. 1926 Revenue Act of 1926 reduces taxes: Too much money being collected. 1939 Revenue statutes codified. One out of 32 citizens pays 4% rate. 1943 One out of three people pays taxes. Withholding on salaries and wages introduced. 875-page Internal Revenue Code of 1954 passes. Considered the most monumental overhaul of federal income tax system to date. 3,000 changes 1954 to tax rules. 1969 Tax Reform Act: Major amendments to 1954 overhaul. 1984 Reagan Tax Reform Act: Most complex bill ever, requires over 180 technical corrections. 1986 Tax Reform Act reduces tax brackets from five or two. 1993 Clinton’s Revenue Reconciliation Act passes by one Vice Presidential vote. 1996 Four bills make over 700 changes, including Medical Savings Accounts and SIMPLE plans. 1997 Taxpayer Relief Act brings more than 800 changes. Child tax credit, Roth IRAs, capital gains reduction, breaks for higher education enacted. 2001 Tax Relief Act creates 441 changes. Lowers tax rates, repeals estate tax, increases contribution limits on 401(k)s and IRAs. The Job Creation and Worker Assistance Act brings business tax relief, including a 5-year net operating loss carryback and extends and adds 2002 depreciation. -

Era/President Foreign Policy Domestic Policy Time Period America: Pre-European -Settlement Patterns: Most Indian Tribes Had Separate Gender Roles

AP US History Review Sheet by Carrie Filipetti and Helen Yang (©2005) Era/President Foreign Policy Domestic Policy Time Period America: Pre-European -Settlement Patterns: Most Indian tribes had separate gender roles. Small, semi permanent settlements. Settled near rivers. Some societies large and complex, such as the Pueblos (irrigation), Mayas (Yucatan Contact Peninsula), and Aztecs/Incas (Central Mex./Peru): established trade, vast empires, religion, calendars, and made scientific discoveries. Iroquois: developed political confederacy, called League of the Iroquois. Defended them against attacks from Americans and Euros during 17 & 18 hundreds. Age of Exploration -Background of Exploration: Improvements in Technology: Renaissance, began using gunpowder, sailing compass, improvements in shipbuilding/mapmaking. 1450- Printing Press. European religious conflicts: Roman Catholic Church threatened by Ottoman (Islamic) Turks. Catholic victory in Spain (1492): Isabella and Ferdinand United. Defeated Moors of Granada. Protestant revolt: everyone Protestant/Catholic wanted to be first to spread ideas of God to Africa, Asia. Expanding Trade: Trade route from Venice and Constantinople blocked in 1453 (controlled by Ottoman Turks, demanded high tax). Had to find new trade route to Asia. First: a way around Africa, discovered by Prince Henry (Portugal): Opened a sea route around South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. 1498—Portuguese Vasco da Gama: first euro to reach India by Prince Henry’s route. Developing Nation-States in Spain, Portugal, France, England, Netherlands. Used them to find riches/spread religion. -Columbus: Funded by Spanish. Sailed from Canary Islands to Bahamas. Brought first interaction with Whites and Indians for long-time period. Led to Columbus Exchange: Indians gave Euros: Beans, corn, sweet potato, tomato, reg. -

Perpetuating Inequality by Taxing Wealth

Fordham Law Review Volume 84 Issue 6 Article 2 2016 Perpetuating Inequality by Taxing Wealth Goldburn P. Maynard Jr. Brandeis School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation Goldburn P. Maynard Jr., Perpetuating Inequality by Taxing Wealth, 84 Fordham L. Rev. 2429 (2016). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol84/iss6/2 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERPETUATING INEQUALITY BY TAXING WEALTH Goldburn P. Maynard Jr.* INTRODUCTION In the decade since Michael Graetz and Ian Shapiro wrote the definitive account of the death tax repeal saga of the late 1990s and early 2000s, Death by a Thousand Cuts: The Fight Over Taxing Inherited Wealth,1 the federal estate tax has proven to be surprisingly resilient. After a one-year hiatus and a two-year temporary reprieve, the levy was made permanent again in 2013.2 At a time when wealth inequality is a topic of major concern, the federal estate tax remains the only levy that is meant specifically to combat the concentration of wealth in the hands of the few. It is also the most progressive part of the tax system, as its burden is borne by the wealthiest Americans. The survival of the estate tax seemingly fits into America’s newfound interest in fighting wealth inequality. -

An Examination of Tax Law and Supply-Side Economics: Creed of Greed Or Opportunity for All

North Dakota Law Review Volume 72 Number 3 Article 10 1996 An Examination of Tax Law and Supply-Side Economics: Creed of Greed or Opportunity for All Marc G. Worthy Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Worthy, Marc G. (1996) "An Examination of Tax Law and Supply-Side Economics: Creed of Greed or Opportunity for All," North Dakota Law Review: Vol. 72 : No. 3 , Article 10. Available at: https://commons.und.edu/ndlr/vol72/iss3/10 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Dakota Law Review by an authorized editor of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EXAMINATION OF TAX LAW AND SUPPLY-SIDE ECONOMICS: CREED OF GREED OR OPPORTUNITY FOR ALL? I. INTRODUCTION Since American Patriots proclaimed their opposition to the oppres- sive colonial rule of King George III with the rallying cry of "no taxation without representation,"' the debate over taxation, in whatever form and in the fullness of time, has run like a thread from revolutionary times to the present. 2 Indeed, this debate is often characterized by radically different views 3 of the role of taxation in a civilized society.4 In the twentieth century, the philosophies of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Ronald W. Reagan aptly demonstrate this polemic. 5 President Roosevelt, perhaps the greatest figure in American politics in the twenti- eth century, believed that taxes were the unavoidable price one must pay to live in a free society. -

Percentage Depletion for Oil–A Policy Issue

INDIANA LAW JOURNAL Volume 30 SUMMER 1955 Number 4 PERCENTAGE DEPLETION FOR OIL-A POLICY ISSUE HARROP A. FREEMAN* Although it has always been recognized that lawyers were "policy makers"' and that, on the solid foundation of training in jurisprudence, principles of law, and tools of the trade, law school graduates were ex- pected to guide public or private clients in policy choices, 2 Yale Law School has more recently urged that policy formation be made the pole-star of the academic curriculum.' But, when such suggestions are made, we are forcefully reminded that we lack adequate material for such study, and. at no point is this more true than in the study of taxation.4 Yet, professors * Professor of Law, Cornell University Law School. 1. BROWN, LAWYERS, LAW SCHOOLS AND THE PUBLIC SERVICE (1948); Frey, Some Thoughts of Law Teaching and the Social Sciences, 82 U. OF PA. L. REV. 463 (1934) ; Harno, The Correlation of Law and College Subjects, 5 Am. L. SCHOOL REV. 85 (1923). 2. Brown, op. cit. supra note 1; CARDOZO, THE NATURE OF THE JUDICIAL PROCESS (1932); FRANK, COURTS ON TRIAL 240 (1949); FULLER, THE LAW IN QUEST OF ITSELF (1940); HOLMES, The Profession of the Law, The Use of Law Schools, and Law and the Courts in COLLECTED LEGAL PAPERS (1920). 3. McDoUGAL AND HABER, PROPERTY, WEALTH, LAND: ALLOCATION, PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT (1948) ; Hale, Economics and Law in THE SOCIAL SCIENCES AND THEIR INTERRELATIONS, C. 12 (Ogburn and Goldenweiser eds. 1927); RoSTOw, A NATIONAL POLICY FOR THE OIL INDUSTRY (1948) and other publications of Yale University Seminar on National Policy.