IN SEARCH of SPEED 2Nd Edition a Collection of “Go Fast” Theory by Peter Galloway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chesapeake Yacht Sales

FROM THE QUARTERDECK MARCH 2012 Championships at Lake Eustis. I’ve seen no The Welcome Cruisers event is results at this time. In addition, several of our scheduled for March 24th. This is the kick Cruisers have been down in the Sunshine State off gathering for the cruising season and is (despite George Sadler’s report of rain in Key expected to set the tone for events to follow. Largo). Thanks to all for carrying the FBYC We look forward to an exciting collection of burgee beyond our home waters. outings including some activities planned around the Op Sail venture in the summer of Registration for Junior Week began on 2012. Feb. 1st. Beginning Opti was at the limit of capacity within 42 hours of going live on the Those of us involved in FBYC Board website. Other aspects of our Junior program meetings have witnessed some changes for are in high demand as well. Race teams are this year. I’m specifically referring to the filling or have filled and the numbers for Opti conference call system we have put in place. The Ullman Sails Seminar “Unlocking Development Team are so high that another At the last meeting seven people were remote the Race Course” took place on Feb. 15th. coaching position for that team is justified. I’m calling in from Vermont to Florida. This system The event was very well attended. Of the 133 looking forward to Junior Week as two of my allows folks who do not live in the Richmond attendees, 50 were non-members of FBYC. -

RS100, and Thank You for Choosing an RS Product

R I G G I N G G U I D E Sail it. Live it. Love it. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. COMMISSIONING 2.1 Preparation 2.2 Rigging the Mast 2.3 Stepping the Mast 2.4 Rigging the Boom 2.5 Hoisting the Mainsail 2.6 Rigging the Gennaker 2.7 Attaching sail numbers 2.8 Completion 3. SAILING HINTS 3.1 Tacking 3.2 Gybing (mainsail only) 3.3 Sailing With the Assymetric Spinnaker 4. TUNING GUIDE 5. MAINTENANCE 5.1 Boat care 5.2 Foil care 5.3 Spar care, and access to bowsprit. 5.4 Sail care 6. WARRANTY 7. APPENDIX 7.1 Useful Websites and Recommended Reading 7.2 Three Essential Knots All terms highlighted in blue throughout the Manual can be found in the Glossary of Terms Warnings, Top Tips, and Important Information are displayed in a yellow box. 1. INTRODUCTION Congratulations on the purchase of your new RS100, and thank you for choosing an RS product. We are confident that you will have many hours of great sailing and racing in this truly excellent design. The RS100 is an exciting boat to sail and offers fantastic performance. This manual has been compiled to help you to gain the maximum enjoyment from your RS100, in a safe manner. It contains details of the craft, the equipment supplied or fitted, its systems, and information on its safe operation and maintenance. Please read this manual carefully and be sure that you understand its contents before using your RS100. This manual will not instruct you in boating safety or seamanship. -

Yachts Yachting Magazine NACRA F18 Infusion Test.Pdf

TEST INFUSION Nacra INFUSION S N A V E Y M E R E J O T O H P Y The Infusion made its debut in top level competition at & Eurocat in May. Jeremy Evans goes flying on the very latest Formula 18. Y T ny new racing boat is judged by its although the Dutch guys racing the top Infusions results. At their first major regatta — were clearly pretty good as well. Eurocat in Carnac in early May, ranked This is the third new Formula 18 cat produced by E A alongside the F18 World championship Nacra in 10 years. They started with the Inter 18 in and Round Texel as a top grade event — Nacra 1996, designed by Gino Morrelli and Pete Melvin S Infusions finished second, third and sixth in a fleet based in the USA. It was quick, but having the of 142 Formula 18. Why not first? The simple main beam and rig so unusually far forward made answer is that Darren Bundock and Glenn Ashby, it tricky downwind. Five years later, the Inter 18 T who won Eurocat in a Hobie Tiger are currently was superseded by a new Nacra F18 designed by the most hard-to-beat cat racers in the world, Alain Comyn. It was quick and popular, but could L YACHTS AND YACHTING 35 S N A V E Y M E R E J S O T O H P Above The Infusion’s ‘gybing’ daggerboards have a thicker trailing edge at the top, allowing them to twist in their cases and provide extra lift upwind. -

Equinox Manual

Racing Manual V1.2 January 2014 Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 3 The Boat ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Positions on a Sigma 38 ................................................................................................................. 4 Points of Sail .................................................................................................................................. 5 Tacking a boat ............................................................................................................................... 6 Gybing a boat ................................................................................................................................ 7 Essential knots all sailors should know ............................................................................................... 8 Bowline ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Cleat Knot ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Clove Hitch ................................................................................................................................... 8 Reef Knot...................................................................................................................................... -

Sailing Instructions

Verve Inshore Regatta Chicago Yacht Club Belmont Harbor, Chicago, IL August 24-26, 2018 SAILING INSTRUCTIONS Abbreviations [SP] Rules for which a standard penalty may be applied by the race committee without a hearing or a discretionary penalty applied by the protest committee with a hearing. [DP] Rules for which the penalties are at the discretion of the protest committee. [NP] Rules that are not grounds for a protest or request for redress by a boat. This changes RRS 60.1(a) 1 RULES 1.1 The regatta will be governed by the rules as defined in The Racing Rules of Sailing. 1.2 Appendices T and V1 shall apply. 1.3 Class rules prohibiting the use of marine band radios and cellular telephones will not apply. All keelboats are required to carry an operating VHF marine-band radio while sailing in these events. This changes International Etchells class rule C.5.2(b)(8). 1.4 Class rules prohibiting GPS navigation devices will not apply. The following conditions will apply to the use of GPS navigation devices: When class rules prohibit the use of a GPS while racing, such a device may be used provided that it will be installed in a position or covered in such a way that no data may be taken from it while sailing. Data produced by such device may be viewed only at the dock or on shore. This changes International Etchells class rule C.5.1(b) and Shields class rule 10.9. 1.5 For the J/70 class only, J/70 Class Rules Part III I.3 (Support Boats) will apply. -

Setting up Your FD to Go Sailing

FD Trim Setting up your FD to go sailing The FD is a complex and powerful dinghy and getting the boat set up correctly for the prevailing conditions makes all the difference between the boat flying along and its being a pig to sail, especially to windward. It is important, therefore, that the significant controls are readily adjustable by the helmsman whilst sailing, so that he can fine tune the rig without loosing way or control. Of course, all the usual boat turning and preparation rules apply to the FD as to any other performance dinghy. Get the centreboard and rudder vertical and in line; get the mast central and upright in the boat; make the mast a tight fit in the step and partners etc. However some aspects of the FD are a bit special so try this way of sorting boat out and getting set for the race. Set up the genoa: The most important control of an FD is the genoa halyard, controlling the mast rake. This needs the purchase of at least 24:1 led to either side of the boat for the helmsman to adjust while hiking. A courser adjustment, say 6:1, is also ideal for changing between the different clew attachment positions available in modern genoas. We use a 6:1 purchase on the back face of the mast which hooks up to the genoa halyard. One end of this goes directly to a clam-cleat for the course adjustment and this marked with a position for each clew. The other end goes to 4:1 purchase running along the boats centreline and led to each side. -

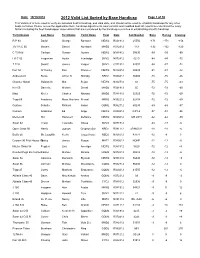

2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap Page 1 of 30 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Design Last Name First Name Yacht Name Fleet Date Sail Number Base Racing Cruising R P 90 David George Rambler NEW2 R021912 25556 -171 -171 -156 J/V I R C 66 Meyers Daniel Numbers MHD2 R012912 119 -132 -132 -120 C T M 66 Carlson Gustav Aurora NEW2 N081412 50095 -99 -99 -90 I R C 52 Fragomen Austin Interlodge SMV2 N072412 5210 -84 -84 -72 T P 52 Swartz James Vesper SMV2 C071912 52007 -84 -87 -72 Farr 50 O' Hanley Ron Privateer NEW2 N072412 50009 -81 -81 -72 Andrews 68 Burke Arthur D Shindig NBD2 R060412 55655 -75 -75 -66 Chantier Naval Goldsmith Mat Sejaa NEW2 N042712 03 -75 -75 -63 Ker 55 Damelio Michael Denali MHD2 R031912 55 -72 -72 -60 Maxi Kiefer Charles Nirvana MHD2 R041812 32323 -72 -72 -60 Tripp 65 Academy Mass Maritime Prevail MRN2 N032212 62408 -72 -72 -60 Custom Schotte Richard Isobel GOM2 R062712 60295 -69 -69 -57 Custom Anderson Ed Angel NEW2 R020312 CAY-2 -57 -51 -36 Merlen 49 Hill Hammett Defiance NEW2 N020812 IVB 4915 -42 -42 -30 Swan 62 Tharp Twanette Glisse SMV2 N071912 -24 -18 -6 Open Class 50 Harris Joseph Gryphon Soloz NBD2 -

Tech Book 2001 Larger Type

Technicalities 2000 Published & Copyright © 2001 by the Santana 20 Class Association Editors: Chris Winnard and Andrew Kerr Published by John Franklin, Class Secretary Publication Design and Prepress by: G2 Marketing Services 1790 Lemming Avenue Eugene, OR 97401 541-344-1979 Technicalities 2000 Table of Contents Getting Started Hoist and Ramp Launching & Retrieving ..............Ralph Taylor ............................................1 Regatta Preparation 5 Tricks to Pull Out of Your Sailbag This Season ......................................Chic Parsons & Dale Waagmeester ....3 Santana 20 Training....................................................Chic Parsons & Dale Waagmeester ....5 Practice Makes Perfect: Growing the Team ..........Andrew Kerr ..........................................5 Regatta Preparation ....................................................Andrew Kerr ..........................................8 Tuning by Feel and Sight ..........................................Lance Purdy ............................................9 Deck Layout Tips If Light is Fast, Lighter is Faster ............................Phillip Infelise ......................................12 Santana 20 Console Setup ........................................Ralph Taylor ..........................................15 Santana 20 Sailing Techniques Smile, the Wind is Howling ......................................Bob Pattison..........................................18 Bill Does Steering ......................................................Bill Jenkins ............................................20 -

Snipe Tuning Guide

Snipe Tuning Guide For any question you may have on tuning your Snipe for speed, contact our experts: Alex Camet 619-226-1415 [email protected] Chris Snow 619-226-1415 [email protected] Eric Heim 619-224-1414 [email protected] Eonedesign.com Follow North Sails on... Snipe Tuning Guide NORTH SAILS Rev. P0526 Dear Snipe sailor: the hull. Pay special attention to the area corrosion. You want to always wet sand around the bailer. the centerboard before sailing unless it is Thank you for choosing North Sails for anodized. your Snipe. As Snipe sailors ourselves we Most top sailors sharpen the last 4-5’ truly share your enthusiasm for this great of the chines and the intersection of the You may want to consider cutting out boat and the worldwide camaraderie transom and hull in the back of the boat. some of the board in the top of the board that Snipe sailors share. We wish you This allows the water to clear away from where it stays inside the boat when many happy seasons of racing your boat the hull more smoothly and promotes down all the way. This makes the board and hope that whenever you have any planning quicker when the breeze is up. lighter and less work for the crew to lift. questions about making your boat go fast Overweight boats can shave off a few that you will give us a call. We are always THE MAST pounds here by cutting away some of pushing to make our sails faster, longer The mast and its tuning are probably the the top of the board. -

The International Flying Dutchman Class Book

THE INTERNATIONAL FLYING DUTCHMAN CLASS BOOK www.sailfd.org 1 2 Preface and acknowledgements for the “FLYING DUTCHMAN CLASS BOOK” by Alberto Barenghi, IFDCO President The Class Book is a basic and elegant instrument to show and testify the FD history, the Class life and all the people who have contributed to the development and the promotion of the “ultimate sailing dinghy”. Its contents show the development, charm and beauty of FD sailing; with a review of events, trophies, results and the role past champions . Included are the IFDCO Foundation Rules and its byelaws which describe how the structure of the Class operate . Moreover, 2002 was the 50th Anniversary of the FD birth: 50 years of technical deve- lopment, success and fame all over the world and of Class life is a particular event. This new edition of the Class Book is a good chance to celebrate the jubilee, to represent the FD evolution and the future prospects in the third millennium. The Class Book intends to charm and induce us to know and to be involved in the Class life. Please, let me assent to remember and to express my admiration for Conrad Gulcher: if we sail, love FD and enjoyed for more than 50 years, it is because Conrad conceived such a wonderful dinghy and realized his dream, launching FD in 1952. Conrad, looked to the future with an excellent far-sightedness, conceived a “high-perfor- mance dinghy”, which still represents a model of technologic development, fashionable 3 water-line, low minimum hull weight and performance . Conrad ‘s approach to a continuing development of FD, with regard to materials, fitting and rigging evolution, was basic for the FD success. -

J/22 Sailing MANUAL

J/22 Sailing MANUAL UCI SAILING PROGRAM Written by: Joyce Ibbetson Robert Koll Mary Thornton David Camerini Illustrations by: Sally Valarine and Knowlton Shore Copyright 2013 All Rights Reserved UCI J/22 Sailing Manual 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction to the J/22 ......................................................... 3 How to use this manual ..................................................................... Background Information .................................................................... Getting to Know Your Boat ................................................................ Preparation and Rigging ..................................................................... 2. Sailing Well .......................................................................... 17 Points of Sail ....................................................................................... Skipper Responsibility ........................................................................ Basics of Sail Trim ............................................................................... Sailing Maneuvers .............................................................................. Sail Shape ........................................................................................... Understanding the Wind.................................................................... Weather and Lee Helm ...................................................................... Heavy Weather Sailing ...................................................................... -

Palaestra-FINAL-PUBLICATION.Pdf

Forum of Sport, Physical Education, and Recreation for Those With Disabilities PALAESTRA Wheelchair Rugby: “Really Believe in Yourself and You Can Reach Your Goals” page 20 www.Palaestra.com Vol. 27, No. 3 | Fall 2013 Therapy on the Water Universal Access Sailing at Boston’s Community Boating Gary C. du Moulin Genzyme Marcin Kunicki Charles Zechel Community Boating Inc. Introduction Sailing and Disability: A Philosophy for Therapy While the sport is less well known as a therapeutic activity, Since 1946, the mission of Community Boating, Inc. (CBI), sailing engenders all the physical and psychological components the nation’s oldest community sailing organization, has been the important to the rehabilitative process (McCurdy,1991; Burke, advancement of the sport of sailing by minimizing economic and 2010). The benefits of this therapeutic and recreational reha- physical obstacles. In addition, CBI enhances the community by bilitative activity can offer the experience of adventure, mobil- offering access to sailing as a vehicle to empower its members ity, and freedom. Improvement in motor skills and coordination, to develop independence and self-confidence, improve communi- self-confidence, and pride through accomplishment are but a few cation and, foster teamwork. Members also acquire a deeper un- of the goals that can be achieved (Hough & Paisley, 2008; Groff, derstanding of community spirit and the power of volunteerism. Lundberg, & Zabriskie, 2009; Burke, 2010). Instead of acting Founded in 2006, in cooperation with the Massachusetts Depart- as the passive beneficiaries of sailing activities, people with dis- ment of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), the Executive Office abilities can be direct participants where social interaction and of Public and Private Partnerships, and the corporate sponsorship teamwork are promoted in the environment of a sailboat’s cock- of Genzyme, a biotechnology company the Universal Access Pro- pit.