Palaestra-FINAL-PUBLICATION.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chesapeake Yacht Sales

FROM THE QUARTERDECK MARCH 2012 Championships at Lake Eustis. I’ve seen no The Welcome Cruisers event is results at this time. In addition, several of our scheduled for March 24th. This is the kick Cruisers have been down in the Sunshine State off gathering for the cruising season and is (despite George Sadler’s report of rain in Key expected to set the tone for events to follow. Largo). Thanks to all for carrying the FBYC We look forward to an exciting collection of burgee beyond our home waters. outings including some activities planned around the Op Sail venture in the summer of Registration for Junior Week began on 2012. Feb. 1st. Beginning Opti was at the limit of capacity within 42 hours of going live on the Those of us involved in FBYC Board website. Other aspects of our Junior program meetings have witnessed some changes for are in high demand as well. Race teams are this year. I’m specifically referring to the filling or have filled and the numbers for Opti conference call system we have put in place. The Ullman Sails Seminar “Unlocking Development Team are so high that another At the last meeting seven people were remote the Race Course” took place on Feb. 15th. coaching position for that team is justified. I’m calling in from Vermont to Florida. This system The event was very well attended. Of the 133 looking forward to Junior Week as two of my allows folks who do not live in the Richmond attendees, 50 were non-members of FBYC. -

RS100, and Thank You for Choosing an RS Product

R I G G I N G G U I D E Sail it. Live it. Love it. CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. COMMISSIONING 2.1 Preparation 2.2 Rigging the Mast 2.3 Stepping the Mast 2.4 Rigging the Boom 2.5 Hoisting the Mainsail 2.6 Rigging the Gennaker 2.7 Attaching sail numbers 2.8 Completion 3. SAILING HINTS 3.1 Tacking 3.2 Gybing (mainsail only) 3.3 Sailing With the Assymetric Spinnaker 4. TUNING GUIDE 5. MAINTENANCE 5.1 Boat care 5.2 Foil care 5.3 Spar care, and access to bowsprit. 5.4 Sail care 6. WARRANTY 7. APPENDIX 7.1 Useful Websites and Recommended Reading 7.2 Three Essential Knots All terms highlighted in blue throughout the Manual can be found in the Glossary of Terms Warnings, Top Tips, and Important Information are displayed in a yellow box. 1. INTRODUCTION Congratulations on the purchase of your new RS100, and thank you for choosing an RS product. We are confident that you will have many hours of great sailing and racing in this truly excellent design. The RS100 is an exciting boat to sail and offers fantastic performance. This manual has been compiled to help you to gain the maximum enjoyment from your RS100, in a safe manner. It contains details of the craft, the equipment supplied or fitted, its systems, and information on its safe operation and maintenance. Please read this manual carefully and be sure that you understand its contents before using your RS100. This manual will not instruct you in boating safety or seamanship. -

An Introduction to Canoeing/Kayaking a Teaching Module

An Introduction to Canoeing/Kayaking A Teaching Module Iowa Department of Natural Resources Des Moines, Iowa This information is available in alternative formats by contacting the DNR at 515/725-8200 (TYY users – contact Relay Iowa, 800/735-7942) or by writing the DNR at 502 East 9th Street, Des Moines, IA 50319-0034. Equal Opportunity Federal regulations prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex or handicap. State law prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, creed, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, national origin, or disability. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to the Iowa DNR, Wallace State Office Building, 502 E. 9th Street, Des Moines, IA 50319-0034. Funding: Support for development of these materials was provided through Fish and Wildlife Restoration funding. Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................1 Objectives........................................................................................................................................1 Materials .........................................................................................................................................1 Module Overview ...........................................................................................................................1 -

Yachts Yachting Magazine NACRA F18 Infusion Test.Pdf

TEST INFUSION Nacra INFUSION S N A V E Y M E R E J O T O H P Y The Infusion made its debut in top level competition at & Eurocat in May. Jeremy Evans goes flying on the very latest Formula 18. Y T ny new racing boat is judged by its although the Dutch guys racing the top Infusions results. At their first major regatta — were clearly pretty good as well. Eurocat in Carnac in early May, ranked This is the third new Formula 18 cat produced by E A alongside the F18 World championship Nacra in 10 years. They started with the Inter 18 in and Round Texel as a top grade event — Nacra 1996, designed by Gino Morrelli and Pete Melvin S Infusions finished second, third and sixth in a fleet based in the USA. It was quick, but having the of 142 Formula 18. Why not first? The simple main beam and rig so unusually far forward made answer is that Darren Bundock and Glenn Ashby, it tricky downwind. Five years later, the Inter 18 T who won Eurocat in a Hobie Tiger are currently was superseded by a new Nacra F18 designed by the most hard-to-beat cat racers in the world, Alain Comyn. It was quick and popular, but could L YACHTS AND YACHTING 35 S N A V E Y M E R E J S O T O H P Above The Infusion’s ‘gybing’ daggerboards have a thicker trailing edge at the top, allowing them to twist in their cases and provide extra lift upwind. -

Sailing Instructions

Verve Inshore Regatta Chicago Yacht Club Belmont Harbor, Chicago, IL August 24-26, 2018 SAILING INSTRUCTIONS Abbreviations [SP] Rules for which a standard penalty may be applied by the race committee without a hearing or a discretionary penalty applied by the protest committee with a hearing. [DP] Rules for which the penalties are at the discretion of the protest committee. [NP] Rules that are not grounds for a protest or request for redress by a boat. This changes RRS 60.1(a) 1 RULES 1.1 The regatta will be governed by the rules as defined in The Racing Rules of Sailing. 1.2 Appendices T and V1 shall apply. 1.3 Class rules prohibiting the use of marine band radios and cellular telephones will not apply. All keelboats are required to carry an operating VHF marine-band radio while sailing in these events. This changes International Etchells class rule C.5.2(b)(8). 1.4 Class rules prohibiting GPS navigation devices will not apply. The following conditions will apply to the use of GPS navigation devices: When class rules prohibit the use of a GPS while racing, such a device may be used provided that it will be installed in a position or covered in such a way that no data may be taken from it while sailing. Data produced by such device may be viewed only at the dock or on shore. This changes International Etchells class rule C.5.1(b) and Shields class rule 10.9. 1.5 For the J/70 class only, J/70 Class Rules Part III I.3 (Support Boats) will apply. -

Setting up Your FD to Go Sailing

FD Trim Setting up your FD to go sailing The FD is a complex and powerful dinghy and getting the boat set up correctly for the prevailing conditions makes all the difference between the boat flying along and its being a pig to sail, especially to windward. It is important, therefore, that the significant controls are readily adjustable by the helmsman whilst sailing, so that he can fine tune the rig without loosing way or control. Of course, all the usual boat turning and preparation rules apply to the FD as to any other performance dinghy. Get the centreboard and rudder vertical and in line; get the mast central and upright in the boat; make the mast a tight fit in the step and partners etc. However some aspects of the FD are a bit special so try this way of sorting boat out and getting set for the race. Set up the genoa: The most important control of an FD is the genoa halyard, controlling the mast rake. This needs the purchase of at least 24:1 led to either side of the boat for the helmsman to adjust while hiking. A courser adjustment, say 6:1, is also ideal for changing between the different clew attachment positions available in modern genoas. We use a 6:1 purchase on the back face of the mast which hooks up to the genoa halyard. One end of this goes directly to a clam-cleat for the course adjustment and this marked with a position for each clew. The other end goes to 4:1 purchase running along the boats centreline and led to each side. -

Nor-Onk-Rs500-Rsaero7-2021-Final-2.Pdf

NOTICE OF RACE Open Dutch Championship RS 500 and RS Aero 7 2021 And Class Championships Aero 5 and 9 organised by Zeilclub Kurenpolder (ZCK) and Aquavitesse, in conjunction with the Dutch RS 500 Class Organisation and the Dutch RS Aero Class Organisation, under the auspices of the RNWA September 18th and 19th 2021 location: the Grevelingen of Bruinisse (Netherlands) The notation ‘[NP]’ in a rule means that a boat may not protest another boat for breaking that rule. This changes RRS 60.1(a). 1 RULES 1.1 The event is governed by the rules as defined in The Racing Rules of Sailing (RRS) . The Prescriptions of the RNWA can be found at http://www.sailing.org/documents/racingrules/national_prescriptions.php. 1.2 The ‘Rules for Championships Sailing, Windsurfing and Kiteboarding ’ will apply for all races of the Open Dutch Championship RS500 and RS Aero7. (only available in Dutch). 1.3 Spare 1.4 Spare 1.5 If there is a conflict between languages the text in the English language will take precedence. 1.6 Every person on board who has his domicile in the Netherlands shall have the appropriate license. 1.7 RRS Appendix T, Arbitration, applies. 2 SAILING INSTRUCTIONS 2.1 The sailing instructions will be available after September 4th 2021 on the websites of the Class Organizations (www.rs500.nl and www.rsaero.nl) and can be downloaded. The Sailing Instructions will also be available displayed on the notice board at the Regatta Office. 3 COMMUNICATION 3.1 The online official notice board is located at: for RS500: RS500.nl/onk-2021 for RS Aero: rsaero.nl 3.2 [DP] While racing, except in an emergency, a boat shall not make voice or data transmissions and shall not receive voice or data communication that is not available to all boats. -

Britannia Yacht Club New Member's Guide Your Cottage in the City!

Britannia Yacht Club New Member’s Guide Your Cottage in the City! Britannia Yacht Club 2777 Cassels St. Ottawa, Ontario K2B 6N6 613 828-5167 [email protected] www.byc.ca www.facebook.com/BYCOttawa @BYCTweet Britannia_Yacht_Club Welcome New BYC Member! Your new membership at the Britannia Yacht Club is highly valued and your fellow members, staff and Board of Directors want you to feel very welcome and comfortable as quickly as possible. As with all new things, it does take time to find your way around. Hopefully, this New Member’s Guide answers the most frequently asked questions about the Club, its services, regulations, procedures, etiquette, etc. If there is something that is not covered in this guide, please do not hesitate to direct any questions to the General Manager, Paul Moore, or our office staff, myself or other members of the Board of Directors (see contacts in the guide), or, perhaps more expediently on matters of general information, just ask a fellow member. It is important that you thoroughly enjoy being a member of Britannia Yacht Club, so that no matter the main reason for you joining – whether it be sailing, boating, tennis or social activity – the club will be “your cottage in the city” where you can spend many long days of enjoyment, recreation and relaxation. See you at the club. Sincerely, Rob Braden Commodore Britannia Yacht Club [email protected] Krista Kiiffner Director of Membership Britannia Yacht Club [email protected] Britannia Yacht Club New Member’s Guide Table of Contents 1. ABOUT BRITANNIA YACHT CLUB ..................................................... -

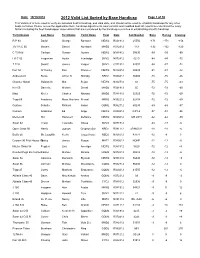

2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap Page 1 of 30 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Design Last Name First Name Yacht Name Fleet Date Sail Number Base Racing Cruising R P 90 David George Rambler NEW2 R021912 25556 -171 -171 -156 J/V I R C 66 Meyers Daniel Numbers MHD2 R012912 119 -132 -132 -120 C T M 66 Carlson Gustav Aurora NEW2 N081412 50095 -99 -99 -90 I R C 52 Fragomen Austin Interlodge SMV2 N072412 5210 -84 -84 -72 T P 52 Swartz James Vesper SMV2 C071912 52007 -84 -87 -72 Farr 50 O' Hanley Ron Privateer NEW2 N072412 50009 -81 -81 -72 Andrews 68 Burke Arthur D Shindig NBD2 R060412 55655 -75 -75 -66 Chantier Naval Goldsmith Mat Sejaa NEW2 N042712 03 -75 -75 -63 Ker 55 Damelio Michael Denali MHD2 R031912 55 -72 -72 -60 Maxi Kiefer Charles Nirvana MHD2 R041812 32323 -72 -72 -60 Tripp 65 Academy Mass Maritime Prevail MRN2 N032212 62408 -72 -72 -60 Custom Schotte Richard Isobel GOM2 R062712 60295 -69 -69 -57 Custom Anderson Ed Angel NEW2 R020312 CAY-2 -57 -51 -36 Merlen 49 Hill Hammett Defiance NEW2 N020812 IVB 4915 -42 -42 -30 Swan 62 Tharp Twanette Glisse SMV2 N071912 -24 -18 -6 Open Class 50 Harris Joseph Gryphon Soloz NBD2 -

Welcome to Byc

WELCOME TO BYC For over 130 years, Britannia Yacht club has provided a quick and easy escape from urban Ottawa into lakeside cottage country that is just fifteen minutes from downtown. Located on the most scenic site in Ottawa at the eastern end of Lac Deschênes, Britannia Yacht Club is the gateway to 45 km of continuous sailing along the Ottawa River. The combination of BYC's recreational facilities and clubhouse services provides all the amenities of lake-side cottage living without having to leave the city. Members of all ages can enjoy sailing, tennis, swimming, childrens' programs and other outdoor activities as well as great opportunities and events for socializing. We have a long history of producing outstanding sailors. Our nationally acclaimed junior sailing program (Learn to Sail) is certified by the Sail Canada (the Canadian Yachting Association) and is structured to nurture skills, self-discipline and personal achievement in a fun environment. BYC has Reciprocal Privileges with other clubs across Canada and the United States so members can enjoy other facilities when they travel. There are a number of different membership categories and mooring rates with flexible payment plans are available. We welcome all new members to our club! Call the office 613-828-5167 or email [email protected] for more information. If you are a new member, please see the Membership Guide; Click Here: https://byc.ca/join See past issues of the club newsletter ~ ‘Full & By’; Click Here: https://byc.ca/members-area/full-by Take a virtual tour of the club house and grounds; Click Here: http://www.byc.ca/images/BYC-HD.mp4 Once again, Welcome to your Cottage in the City!! Britannia Yacht Club, 2777 Cassels Street, Ottawa, ON K2B 6N6 | 613-828-5167 | [email protected] For a great social life we’re the place to be! There’s something for everyone at BYC! Call the office to get on the email list to Fun Events ensure you don’t miss out! In addition, check the; ‘Full&By’ Fitness Newsletter, Website, Facebook, bulletin boards, posters, Tennis and Sailing News Flyers. -

The Keystone State's Official Boating Magazine I

4., • The Keystone State's Official Boating Magazine i Too often a weekend outing turns to tragedy because a well- meaning father or friend decides to take "all the kids" for a boat ride, or several fishing buddies go out in a small flat- bottomed boat. In a great number of boating accidents it is found that the very simplest safety precautions were ignored. Lack of PFDs and overloading frequently set the stage for boating fatalities. Sadly, our larger group of boaters frequently overlooks the problem of boating safety. Boaters in this broad group are owners of small boats, often sportsmen. This is not to say that most of these folks are not safe boaters, but the figures show that sportsmen in this group in Pennsylvania regularly head the list of boating fatalities. There are more of them on the waterways and they probably make more frequent trips afloat than others. Thus, on a per capita or per-hour-of-boating basis, they may not actually deserve the top spot on the fatality list. Still, this reasoning does not save lives and that is what is WHO HAS BOATING important. ACCIDENTS? Most boating accidents happen in what is generally regarded as nice weather. Many tragedies happen on clear, warm days with light or no wind. However, almost half of all accidents involving fatalities occur in water less than 60 degrees. A great percentage of these fatal accidents involved individuals fishing or hunting from a john boat, canoe, or some other small craft. Not surprising is that victims of this type of boating accident die not because of the impact of the collision or the burns of a fire or explosion, but because they drown. -

Sail Share MEMBER & SAFETY INFORMATION

Sail Share MEMBER & SAFETY INFORMATION Please Print Clearly Name: _______________________________________________________________ Address: _____________________________________________________________ City: __________________ Prov: _____________ Postal Code: _________________ Phone: [Cell]_________________________ [Other]___________________________ Email: ______________________________________________________________ Date of Birth (YYYY-MM-DD): __________________________________________ PROGRAM ENROLLED IN (please circle): Club: NSC BYC Sail Share: Big Boat Small Boats Sail Share Level: Level 1 Level 2 Level 3 Sail Share Qualification: Skipper Partner Crew EMERGENCY CONTACT Name: ____________________________________ Relation: __________________ Phone: [Cell]_________________________ [Other]___________________________ Are there any medical problems/conditions we should be aware of?: YES NO If yes, please elaborate: _________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Do you have any allergies? YES NO If yes, please elaborate: _________________________________________________ Swimming ability: STRONG AVERAGE WEAK NON-SWIMMER Please note: The information provided is confidential. V. 2019-09 Sail Share Member Acknowledgement & Waiver This must be signed by all members of the Sail Share program and must be accompanied by a completed safety form!! ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I hereby acknowledge receipt of the Sail Share information package provided by Advantage Boating Inc. and agree to