Oui a La Biennale De São Paulo Dec 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020

Sabbatical Leave Report 2019 – 2020 James MacDevitt, M.A. Associate Professor of Art History and Visual & Cultural Studies Director, Cerritos College Art Gallery Department of Art and Design Fine Arts and Communications Division Cerritos College January 2021 Table of Contents Title Page i Table of Contents ii Sabbatical Leave Application iii Statement of Purpose 35 Objectives and Outcomes 36 OER Textbook: Disciplinary Entanglements 36 Getty PST Art x Science x LA Research Grant Application 37 Conference Presentation: Just Futures 38 Academic Publication: Algorithmic Culture 38 Service and Practical Application 39 Concluding Statement 40 Appendix List (A-E) 41 A. Disciplinary Entanglements | Table of Contents 42 B. Disciplinary Entanglements | Screenshots 70 C. Getty PST Art x Science x LA | Research Grant Application 78 D. Algorithmic Culture | Book and Chapter Details 101 E. Just Futures | Conference and Presentation Details 103 2 SABBATICAL LEAVE APPLICATION TO: Dr. Rick Miranda, Jr., Vice President of Academic Affairs FROM: James MacDevitt, Associate Professor of Visual & Cultural Studies DATE: October 30, 2018 SUBJECT: Request for Sabbatical Leave for the 2019-20 School Year I. REQUEST FOR SABBATICAL LEAVE. I am requesting a 100% sabbatical leave for the 2019-2020 academic year. Employed as a fulltime faculty member at Cerritos College since August 2005, I have never requested sabbatical leave during the past thirteen years of service. II. PURPOSE OF LEAVE Scientific advancements and technological capabilities, most notably within the last few decades, have evolved at ever-accelerating rates. Artists, like everyone else, now live in a contemporary world completely restructured by recent phenomena such as satellite imagery, augmented reality, digital surveillance, mass extinctions, artificial intelligence, prosthetic limbs, climate change, big data, genetic modification, drone warfare, biometrics, computer viruses, and social media (and that’s by no means meant to be an all-inclusive list). -

PREFACE DE PIERRE RESTANY Au Terme D'un

PREFACE DE PIERRE RESTANY Au terme d©un parcours déjà vieux de plus de 30 ans et que je me suis attaché à suivre depuis le début de son émergence, ma réflexion sur le travail de Fred Forest s©est opérée à plusieurs niveaux. Chaque constat a été pour moi l©occasion de mesurer l©envergure conceptuelle de la notion d©art à travers sa projection directe sur la trame vitale du tissu social. C©est toujours l©artiste en Forest qui m©a permis d©apprécier, par rapport à la pulsion expressive collective, l©évolution du domaine conceptuel de l©esthétique. C©est en effet un seul et même artiste, Fred Forest, qui est passé de l©art sociologique à l©anthropologie télématique, en passant par l©esthétique de la communication. Fred Forest est apparu sur le panora- ma expansif de ce questionnement artistique au moment où l©Occident vivait le symptôme avant-coureur d©un changement radical de société et du système de production, c©est-à-dire en mai 1968. C©est à ce moment- là que le rapport art-communication a changé à la fois de vitesse et d©amplitude. La communication, en fait, a acquis une nouvelle conscience de son territoire artistique, des droits et du devoir qui en ré- sultaient : sa vertu critique et sa vertu d©éveil en ce qui concerne les cri- tères humains et humanistes de la transmission d©un message gratifiant dans sa vérité et non plus dans sa beauté. Cette réflexion sur le caractère profondément humain et poétique de l©ensemble des dispositifs et des méthodes d©intervention sur le social était, bien évidemment, dans l©air du temps au début des années 70 et elle a constitué le moment fort des activités du collectif d©art sociologique qui a rassemblé Hervé Fisher, Fred Forest et Jean-Marc Thénot. -

To Save Philosophy in a Universe of Technical Images

FLUSSER STUDIES 22 Baruch Gottlieb To Save Philosophy in a Universe of Technical Images “Linguistic communication, both in the spoken and written world, are no longer capable of transmitting the thoughts and concepts which we have concerning the world. It has been clear for several centuries now that, if we want to understand the world, it is not sufficient to describe it by words. It is necessary to calculate the world. So that science has had ever more recurrence to numbers, which are images of thoughts. For instance, “2” is the ideogram for the concept “pair” or “couple”. Now, this ideographic code, which is the code of numbers, has been developed, in a very refined way, lately, by computers. Numbers are being transcoded into digital codes and digital codes are, themselves, being transcoded into synthetic images. So it is my firm belief, that if you want to have a clear and distinct communication of your concepts, you have to use synthetic images, no longer words. And this is a veritable revolution in thinking” (Flusser 2010: 36)1 The invention of the photograph is a pivotal moment in Vilém Flusser's history of humanity. What is so special, so transformative about the discovery of photography? With Flusser, it is often helpful to tap back into etymology and look again at the words ‘photos’ (φωτός: light) and ‘graphein’ (γράφειν: writing). For Flusser, the photograph is a technical or synthetic image, an image that is programmed and projected from the scientific knowledge, which generated the chemical processes and materials where the image appears. -

8-Replart8ecolede Vie.Doc 1.Pdf

Dans la société du futur, le véritable moteur de la culture vivante devrait être l’art sous toutes les formes actives, susceptibles de con- trebalancer le poids et l’emprise d’une technologie toujours plus prégnante et envahissante. C’est à partir des écoles d’art et de leurs impulsions créatives que peut s’organiser un enseignement « social », ou encore, pour mieux le définir, « sociocritique ». Un enseignement destiné à restaurer ce qu’on peut appeler : la qualité de vie et une écologie de l'esprit ! Et, au-delà de la qualité de vie, un enseigne- ment visant à redonner, à chacun et à tous, le sens de l’harmonie et de valeurs esthétiques authentiquement vécues. Ce projet suppose de « repenser » profondément l’enseignement de l’art, de réaména- ger la nature de ses contenus, et surtout de lui donner une mission qui lui attribue un rôle déterminant dans la construction de la société à venir. Une société qui, compte tenu des évolutions des mentalités et des niveaux de vie, aspirera, de plus en plus, à privilégier les ver- tus du sens et la qualité de vie, sur la consommation. Il importe, en priorité, que l’école d’art se prémunisse contre toutes les formes d’académismes, que ce soient celles du passé comme celles du pré- sent. Ces dernières, plus pernicieuses encore, car elles se présentent avec toutes les séductions du moment, parées du label « tendance ». Un label devenu irrésistible en matière de suivisme grégaire. Les productions des étudiants des écoles d’art, pour leur grande majorité font preuve d’une désolante répétition de formes et d’un confor- misme consternant. -

Missing in Action: Agency and Meaning in Interactive Art1 Kristine Stiles and Edward A. Shanken

Missing In Action: Agency and Meaning In Interactive Art 1 Kristine Stiles and Edward A. Shanken A legend of interactivity Cynthia Mailman fell through the roof of a garage on which she was dancing as a participant in Al Hansen’s “Hall Street Happening” (1963). Bleeding and hurt, she screamed for help but initially no one came to her rescue; participants and viewers alike presumed her action was part of the happening and ignored her pleas for assistance. Writing about the event several years later, Hansen (1965: 17) remarked, I ran out into the warm midnight-Brooklyn slum street and looked up and down each way—my first impulse was to hitchhike to Mexico and forget the whole thing. Then an ambulance and the police arrived…It was a fine bit of mayhem and quite abstract. (Hansen 1965: 17) For better or worse, only a few happenings resembled Hansen’s “Hall Street Happening” in its obliteration of the tangible, objective difference between aesthetic and ordinary events, artist and spectator. This slippage is one reason why Allan Kaprow abandoned happenings less than a decade after theorizing them in the mid-1950s. Even though the aims he outlined for happenings included keeping “the line between art and life…as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible,” and “eliminat[ing] audiences entirely,” Kaprow found that audiences were culturally unprepared to interact responsibly in constructing a work of art (Kaprow 1965, reprinted in Stiles & Selz 1996, pp. 709, 713; Kaprow 1966). While little has changed in the public’s capacity to interact in art or life, fostering audience agency remains a utopian activist goal for many artists and is presented as an ineluctable formal quality of digital multimedia. -

Abstracts 2012

100TH ANNUAL CONFERENCE L O S A N G E L E S FEBRUARY 22–25, 2012 ABSTRACTS ABSTRACTS 2012 100th Annual Conference, Los Angeles Wednesday, February 22–Saturday, February 25, 2012 50 Broadway, 21st Floor New York, NY 10004 www.collegeart.org College Art Association 50 Broadway, 21st Floor New York, NY 10004 www.collegeart.org Copyright © 2012 College Art Association All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Sessions are listed alphabetically according to the name of the chair. Abstracts 2012 is produced on a very abbreviated schedule. Although every effort is made to avoid defects, information in this book is subject to change. CAA regrets any editorial errors or omissions. We extend our special thanks to the CAA Annual Conference Committee members responsible for the 2012 program: Sue Gollifer, University of Brighton, vice president for Annual Conference, chair; Sharon Matt Atkins, Brooklyn Museum of Art; Peter Barnet, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Brian Bishop, Framingham State University; Connie Cortez, Texas Tech University; Ken Gonzales-Day, Scripps College; and Sabina Ott, Columbia College Chicago. Regional Representatives: Stephanie Barron, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and Margaret Lazzari, University of Southern California. We also thank all the volunteers and staff members who made the conference possible. Cover: Photograph provided by Security Pacific National Bank Collection, Los Angeles Public Library. Design: Ellen Nygaard CAA2012 FEBRUARY 22–25 3 Contents CAA International Committee 11 Concerning the Spiritual in Art: Kandinsky’s 19 Confrontation in Global Art History: Past/Present; Pride/ Radical Work at 100 Prejudice Surrounding Art and Artists Chairs: Susan J. -

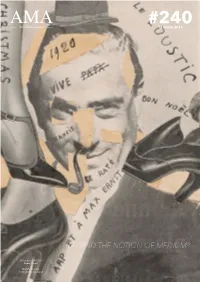

Beyond the Notion of Medium?

#240 18 march 2016 BEYOND THE NOTION OF MEDIUM? Tableau Rastadada (1920) Francis Picabia MoMA, New York © 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich #240 • 18 MARCH 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS P. 5 P.11 BEYOND THE NOTION OF MEDIUM? TOP STORIES P.14 P.16 P.20 MUSEUMS CARINE FOL GALLERIES P.21 P.26 P.27 GALERIE DES DATA MODERNES ARTISTS NIELE TORONI P.33 P.34 AUCTION FAIRS AND FESTIVALS 2 This document is for the exclusive use of Art Media Agency’s clients. Do not distribute. Subscribe for free. 10TH ANNIVERSARY THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON CONTEMPORARY DRAWING IN FRANCE CARREAU DU TEMPLE AUDITORIUM Under the chairmanship of Fabrice Hergott, director of Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris. International speakers. WEDNESDAY, MARCH 30TH THURSDAY MARCH 31TH 10am – 10.30am: Opening 10am – 11am: Drawing and its market 10.30am – 11.30am: Drawing and its collection 11.30am – 12.30am: Drawing and its teaching 11.45am – 12.30am: Artist interview 12.30am – 1pm: Drawing and its teaching, artist interview 1.30pm – 2.30pm: Drawing and its venues 2pm – 3pm: Drawing and its researches I: analysis and interpretation 3pm – 4pm: Drawing and its limits 4.30pm – 5.30pm : Drawing and its exhibition 3.30pm – 4.30pm: Drawing and its researches II: subject and territory 6pm – 6.30pm: Artist interview 5pm – 5.30pm: Artist interview 7pm – 8pm: Drawing and its conservation 6pm – 7pm: Drawing and its collectors Artists, collectors and art world professional Collection, exhibition, creation, conservation, teaching, art market ... two days to debate on drawing Free access upon fair’s tickets presentation, reservations recommended (access on the limit of available seats) Program and contributors: www •drawingnowparis•com AP sympo GB (210x297).indd 1 09/03/16 11:52 BEYOND THE NOTION OF MEDIUM? ince 20 February, the Vancouver Art Gallery has been hosting the biggest exhibition in its history: “MashUp: The Birth Of Modern Culture” — open until 12 June 2016. -

Fred Forest : Catalogue Raisonné (1963-2008)

UNIVERSITÉ DE PICARDIE/AMIENS – JULES VERNE ÉCOLE DOCTORALE EN SCIENCES HUMAINES ET SOCIALES THÈSE DE DOCTORAT D’HISTOIRE DE L’ART ISABELLE LASSIGNARDIE FRED FOREST : CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ (1963-2008) COMMENTAIRE SOUS LA DIRECTION DE LAURENCE BERTRAND DORLÉAC SOUTENANCE : 26 MARS 2010 FACULTE DES ARTS, UPJV, AMIENS MEMBRES DU JURY: LAURENCE BERTRAND DORLÉAC LESZEK BROGOWSKI FRANCOISE COBLENCE ÉVELYNE TOUSSAINT 1 ISABELLE LASSIGNARDIE FRED FOREST : CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ (1963-2008) COMMENTAIRE 2 Résumé Cette thèse est une étude de l’œuvre de l’artiste Fred Forest à travers le catalogue raisonné de ses travaux réalisés entre 1963 à 2008. Il s’agit de saisir les divers aspects pratiques et théoriques déployés par l’artiste : dans le cadre d’un art dit sociologique prenant le quotidien et l’ordinaire comme matériau d’observation, terrains d’action et d’animation ; par la formulation d’une esthétique de la communication dont l’objectif est la mise en évidence des médiums et technologies employées ; dans l’usage des médias de masse et des moyens de communication et de diffusion de l’information comme supports des œuvres ; de l’événement et de la communication comme parties intégrantes de la démarche artistique ; à travers les notions de participation et d’implication des récepteurs dans les dispositifs des œuvres. Mots clés : Fred Forest ; art contemporain ; art sociologique (mouvement) ; esthétique de la communication ; communication ; médias de masse ; internet ; télématique ; télécommunications ; presse ; art participatif ; participation ; esthétique relationnelle. Thesis abstract This thesis is a study of the artistic productions of Fred Forest through the comprehensive catalogue of his work from 1963 to 2008. -

Fred Forest 12 July - 28 August 2017 Fred Forest

COMMUNICATIONS AND PARTNERSHIPS DEPARTMENT PRESS KIT FRED FOREST 12 JULY - 28 AUGUST 2017 FRED FOREST #ExpoFredForest FRED FOREST 12 JULY - 28 AUGUST 2017 17 july 2017 SUMMARY communication and partnerships department 75191 Paris cedex 04 1. PREss RELEASE PAGE 3 director Benoît Parayre 2. AN INTRODUCTION BY CURATOR ALICIA KNOCK PAGE 4 telephone 00 33 (0)1 44 78 12 87 email 3. THE EXHIBITION PAGE 6 [email protected] press officer 4. INTERVIEW WITH FRED FOREST PAGE 9 Dorothée Mireux telephone 00 33 (0)1 44 78 46 60 5. VISUALS AVAILABLE FOR THE PREss PAGE 10 email [email protected] 6. PRACTICAL INFORMATIONS PAGE 14 www.centrepompidou.fr #ExpoFredForest 17 july 2017 PRESS RELEASE communication and partnerships department 75191 Paris cedex 04 FRED FOREST director 12 JULY - 28 AUGUST 2017 Benoît Parayre telephone FORUM, LEVEL -1 00 33 (0)1 44 78 12 87 email This exhibition takes “media-man” Fred Forest’s notion of “territory” as a guiding theme [email protected] to survey the fifty-year career of this pioneer of a participatory, sociological art. It opens press officer with Territoire du m² artistique, a work created in 1977, the year of the Centre Pompidou’s Dorothée Mireux foundation, before going on to explore the development of Forest’s work from the early telephone “screen-paintings” and “blanks to be filled” to his critical media performances. 00 33 (0)1 44 78 46 60 email [email protected] The territories Forest engages with are many, from the filled space of painting and the media to the voids he sets about creating, from the flow of the media to the bounded institution, www.centrepompidou.fr from local scale to planetary utopia, from the land at Anserville - his property and work of art - Fred Forest to territories virtual or invisible. -

Contemporary Art As “Immatériaux”

Contemporary Art as “Immatériaux”: Yesterday and Today Francesca Gallo In1985astoday,thehistoricalandcriticalinterestofLes Immatériaux lies,in myopinion,inthewayitopposedthetrendtowardsthetriumphoftraditional valuesthatmarkedthe1980s.Thiswasadecadeinwhich,inboththepolitical andculturalarenas,theWesternworldwitnessedthegradualadvanceand dominanceofconservativepositions,withthegreatsuccessofareturnto thevariousformsofpainting:Transavanguardia,NeueWilde,NewExpres- sionism,andsoon.Les Immatériauxshouldbeunderstoodasakindof“Man- ifestoofTechnophilicPostmodernism”,ofwhichJean-FrançoisLyotardwasan interpreter. WhileLyotardlefthisstamponLes Immatériauxespeciallythroughthework hedidontheexhibitionasamedium–theorganizationanddisplay,the soundtrack,thecatalogue,etc.,aretheveryareasinwhichonecansense thehandofthephilosopher1–,fortheselectionoftheworks,Lyotardoften reliedonspecialists(suchasAlainSayagforthephotography,orBernard Blistèneforfinearts).Indeed,afterstudyingthedocumentsinthearchives oftheCentrePompidou,2onecanunderstandthatthecollaborationwiththe NationalMuseumofModernArt(theartdepartmentoftheCentrePompidou, 1 Cf.RosalindKrauss,“Lemuséesansmurdupostmodernisme”,Cahiers du MNAM,no. 17–18(1986):152–158;ReesaGreenberg,BruceW.Ferguson,SandyNairne(eds),Thinking about Exhibition (London&NewYork:Routledge,1996); JeanDavallon,L’exposition à l’oeuvre (Harmattan:Paris,2000). 2 IdedicatedmyPhDtoLes ImmatériauxandLyotard’sinterestincontemporaryart.See FrancescaGallo,Les Immatériaux. -

Bookchin-Curriculum Vitae

Natalie Bookchin -Curriculum Vitae SOLO EXHIBITIONS and INSTALLATIONS 2018 Natalie Bookchin, Retracos de la Multitud, La Virreina, Center for the Image, Barcelona, Spain Natalie Bookchin, Network Effects, Cummings Art Galleries, Connecticut College, New London, CT Natalie Bookchin, Testament, Cinema 3, Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, Australia 2017 Mass Ornament, New Media Gallery, Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA 2012 Now he’s out in public and everyone can see, LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions), Los Angeles, CA 2009 Testament, LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art), Los Angeles, CA 2004 agoraXchange (with Jackie Stevens), Tate Museum online 2002 Metapet Installation, MOCA at the Pacific Design Center, Los Angeles Metapet (metapet.net), Creative Time in association with Hamaca, Barcelona 2003, ARTPORT, Whitney Museum of American Art, online 2000 The Universal Page (with Alexei Shulgin), Walker Art Center online 2001 The Intruder installation, La Compagnie, Marseille, France 1999 Searching for the Truth online The Intruder online 1996 Stolen Goods (with Elizabeth Cohen), Maryland Art Place, Baltimore, MD 1995 Stolen Goods (with Elizabeth Cohen), Southern Exposure Gallery, San Francisco, CA 1993 Work, School 33 Art Space, Baltimore, MD 1991 Playing House, Franklin Furnace, New York, NY SELECT SOLO SCREENINGS 2018 Australian Cinematheque, Queensland Art Gallery, Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis, the Netherlands 2017 Cinema Verite, Tehran, Iran Zimmerli -

Lily Woodruff

Lily Woodruff Participatory Art and Institutional Critique in France, 1958–1981 Dis- ordering the Establish- ment DISORDERING THE ESTABLISHMENT Woodruff_3PP.indd 1 3/24/20 2:36 PM DIS- ORDERING THE ESTABLISH- MENT Participatory Art and Institutional Critique in France, 1958–1981 Lily Woodruff Duke University Press Durham and London 2020 Woodruff_3PP.indd 3 3/24/20 2:36 PM © 2020 Duke University Press This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non- Commercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Designed by Drew Sisk Typeset in Portrait Text and Antique Olive by BW&A Books, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Woodru, Lily, [date] author. Title: Disordering the establishment : participatory art and institutional critique in France, 1958–1981 / Lily Woodru. Other titles: Art history publication initiative. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Series: Art history publication initiative | includes bibliographical references and index. Identiers: 2019041827 (print) | 2019041828 (ebook) ¡¢ 9781478007920 (hardcover) ¡¢ 9781478008446 (paperback) ¡¢ 9781478012085 (ebook) Subjects: ¡¥: Buren, Daniel. | Cadere, André, 1934–1978. | Collectif d’art sociologique. | Groupe de recherche d’art visuel. | Arts and society—France. | Interactive art—France. | Art—Political aspects—France. | Art criticism— France—History—20th century. | Art, French—Government policy—France. | Arts, Modern—20th century. Classication: ®¯°±.¡² ³²² 2020 (print) | ®¯°±.¡² (ebook) | ´´ 709.05/015—dc23 record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041827 ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019041828 Cover art: André Cadere, Avenue des Gobelins, Paris, April 1973.