Chinasince1644.Com

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Application to Become a Member of International Safe Community Network

Application to Become a Member of International Safe Community Network Wanlian Subdistrict, Shenhe District, Shenyang, Liaoning, China October, 2010 1 1. Overview of Wanlian Subdistrict Located in the central part of Shenhe District of Shenyang City, Wanlian Subdistrict covers an area of 1.004 square kilometers with four communities. By February 2010, there are 16,921 households and 38,398 residents, among which 8,277 old people account for 21.5% of total residents; 3,126 children 8.1%; 514 disabled people 1.3%; 339 poor people 1.9%. (Community Figure of Wanlian Office ) Population Statistics of Wanlian Community from 2007 to 2009 Population 2007 2008 2009 Statistics vs Age Groups 0-14 4221 4247 4590 15-24 4493 4521 4886 25-64 29545 29724 32120 65-79 5430 5464 5904 80- 943 949 1025 1 Total 44632 44905 48525 The community is abundant in science, technology and education resources. There are such large scientific research units as 606 Institute, Middling Shenyang Design Academy, Photosensitive Academy, Vacuum Academy and so on with the military unit- Shen Kong Headquarters. There are all kinds of schools and 18 kindergartens as well as 363 small medium and large sized enterprises and public institutions. The community health station can provide services for the whole community, which develops the six-in-one hygienic service integrating prevention, medical care, recovery, healthy education and family planning at regular intervals. The citizen fitness ground is the largest one in Shenyang, which covers an area of 10,000 square meters in the community. Almost 5,000 exercisers are attracted by 354 fitness facilities every day. -

Question About Simon Leys/Pierre Ryckmans

H-Asia Question about Simon Leys/Pierre Ryckmans Discussion published by Nicholas Clifford on Friday, September 4, 2015 Sorry if this is going to the wrong place, but it's the sort of relatively simple question that it was possible to ask on H-ASIA in its earlier incarnation. Is this the appropriate place to put it? and if not, where should I try? Many thanks. I'm trying to find out exactly when "Simon Leys" was publically identified as "Pierre Ryckmans," at the time of his arguments with a powerful group of French academic Maoists. His Habits neufs du président Mao (The Chairman’s New Clothes) a chronicle of the Cultural Revolution, written in Hong Kong and based on the Chinese press and other sources) came out in France in 1971. Then, after a stay of six months in Beijing attached to the new Belgian embassy, he wrote Ombres chinoises (Chinese Shadows) which appeared in 1974. In 1975-76 he had a tussle with the French scholar Michelle Loi, whose primary interest lay in Lu Xun (whom Leys admired enormously, as he did George Orwell). In 1976 she published (in Switzerland) a brief pamphlet called Pour Luxun: réponse à Pierre Ryckmans (For Lu Xun: reply to Pierre Ryckmans) attacking him and his views on China and linking him to reactionary circles in American China studies, and those Americans who (she says) actually preferred Zhou Zuoren (Lu Xun’s collaborationist brother) to Lu Xun himself. She herself, though admitting the problems the CCP gave Lu Xun prior to his death in 1936, managed to put the blame not on Mao and the Maoists, but on Liu Shaoqi, Zhou Yang, and some of the others who were disgraced during the Cultural Revolution, and had not yet been rehabilitated at the time of her writing. -

Annual Review 2017–2018

Australia-China Institute for Arts and Culture Annual Review 2017–2018 ANNUAL REVIEW 2017–2018 Vision Statement China’s rapid emergence as a ACIAC positions itself as a hub and global economic and political national resource centre for cultural power is reshaping the world. For exchange between Australia, Australia, this means an urgent China and the Sinosphere, and for need to know about it not just as collaborative action in the arts and its largest trading partner but other cultural fields. It will build on as a centuries old neighboring the strengths of Western Sydney culture, and learn to engage with University and on existing exchange it in a culturally smart way. The programs in the University. It will Australia-China Institute for Arts help enhance existing exchanges and Culture (ACIAC) was founded between the University and partner for the purpose of facilitating this universities overseas, particularly need. ACIAC also offers to help in mainland China, Taiwan, Hong forge bilateral understanding Kong and Singapore. It will launch between the two peoples and significant new research programs enable development of deeper ties of relevance to the Australia-China between the two countries through relationship, and will engage with the an open, intellectual and dynamic local community in Western Sydney engagement. and particularly with ethnic Chinese groups, businesses and individuals and seek support to ensure its long- term future. Artwork by Shen Wednesday westernsydney.edu.au/aciac 3 AUSTRALIA-CHINA INSTITUTE FOR ARTS AND CULTURE Director’s Report The year of 2018 has been a time of steady completed during the year,and they are The Institute has, through its multiple events, growth for the Australia-China Institute for research fellow Dr Xiang Ren’s internationally turned itself into an important base for Arts and Culture. -

Manchu Grammar (Gorelova).Pdf

HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 1 MANCHU GRAMMAR HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 2 HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES HANDBUCH DER ORIENTALISTIK SECTION EIGHT CENTRAL ASIA edited by LILIYA M. GORELOVA VOLUME SEVEN MANCHU GRAMMAR HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 3 MANCHU GRAMMAR EDITED BY LILIYA M. GORELOVA BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2002 HdO.Gorelova.7.vw.L 25-04-2002 15:50 Pagina 4 This book is printed on acid-free paper Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Gorelova, Liliya M.: Manchu Grammar / ed. by Liliya M. Gorelova. – Leiden ; Boston ; Köln : Brill, 2002 (Handbook of oriental studies : Sect.. 8, Central Asia ; 7) ISBN 90–04–12307–5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gorelova, Liliya M. Manchu grammar / Liliya M. Gorelova p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section eight. Central Asia ; vol.7) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9004123075 (alk. paper) 1. Manchu language—Grammar. I. Gorelova, Liliya M. II. Handbuch der Orientalis tik. Achte Abteilung, Handbook of Uralic studies ; vol.7 PL473 .M36 2002 494’.1—dc21 2001022205 ISSN 0169-8524 ISBN 90 04 12307 5 © Copyright 2002 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by E.J. Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA. -

The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE HALL OF USELESSNESS: COLLECTED ESSAYS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Simon Leys | 464 pages | 02 Dec 2012 | Black Inc. | 9781863955850 | English | Melbourne, Australia The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays PDF Book What made Leys most remarkable was his depth, his continuous effort to try to get to the bottom of things, to understand them, and to render them with the great simplicity proper of the people who really worked through them. Maeve Binchy. How Did I Get Here? Simon Leys died just short of two years ago. Simon Leys is one writer who is possessed of intelligence, wide learning, facility for the written word, and a clear minded logic that cuts through to the core of the matter. After his imprisonment on St Helena in , Napoleon manages to escape, having left an imposter, a close double, in his place. We are experiencing technical difficulties. I imagine Simon would have very little patience for the no-sacrifice, lip-service, sentimentality posing as critical thinking and actual involvement that seems to be all the rage today, facilitated as it is by the bully-pulpit-in-every- pot, medium of the internet. Continuity is not ensured by the immobility of inanimate objects, it is achieved through the fluidity of the successive generations. These are matched with his own highly-quotable phrases, sentences and whole paragraphs. If one did not already come to the conclusion from what I have just written, let me point out that Leys was also a Christian. Rarer still that that person would be a translator of Chinese. This collection is a collection of all of Leys' finest es Simon Leys or Pierre Ryckmans was a Belgian-Australian writer, professor of Chinese literature at University of Sydney, translator, sinologist and, frankly, an all round man of the arts. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

1. Introduction

Andy Jarvis:Users:AndysiMac:Public:ANDY'S IMAC JOBS:14446 - EE - VU (EE3 fn):VU PRINT 9780857939630 PRINT 1. Introduction Economic growth has rightly attracted major attention from economists and policy makers. It is vital from the point of view of human welfare, and challenging intellectually, to attempt to answer basic questions related to the past, present, and future performance of nations in economic develop- ment: Why are some countries rich while others are poor? What factors have enabled some poor countries to achieve miraculous success in catch- ing up with rich countries? Is the disparity in per capita income between rich and poor countries decreasing? Addressing these questions requires rigorous theories and robust empirical studies. In these efforts, one needs not only well- established concepts but also in- depth knowledge of promi- nent development stories, not only knowledge of development patterns in the past events but also the current dynamics that are shaping the trends in the world’s future economic growth. Of these questions, none is more important than what has produced remarkable economic growth in Asia. In a single lifetime, countries have been lifted from rural underdevelopment to the living standards of developed econ- omies. According to World Bank (2013), if China can complete this process in the next 20–30 years, the number of people living in high- income econo- mies would more than double.1 If India could achieve the same, then for the first time in modern human history, the majority of the world’s population would enjoy high- income living standards, with all the immense benefits in human welfare that would follow from this. -

Herbert Allen Giles (1845-1935) and Pu Songling’S Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio

Herbert Allen Giles (1845-1935) and Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio John Minford Culture & Translation Series Lecture Three Hang Seng Management College 27 February 2016 It must however always be borne in mind that translators are but traitors at the best, and that translations may be moonlight and water while the originals are sunlight and wine. — Herbert Giles, 16 October 1883 Dear Land of Flowers, forgive me! — that I took These snatches from thy glittering wealth of song, And twisted to the uses of a book Strains that to alien harps can ne’er belong. Thy gems shine purer in their native bed Concealed, beyond the pry of vulgar eyes; Until, through labyrinths of language led, The patient student grasps the glowing prize. Yet many, in their race toward other goals, May joy to feel, albeit at second-hand, Some far faint heart-throb of poetic souls Whose breath makes incense in the Flowery Land. — Herbert Giles, October 1898, Cambridge Chronology Born 1845, son of John Allen Giles (1808-1884), unconventional Anglican priest Educated at Charterhouse School 1867: Entered China Consular Service, stationed in Peking trained as Student Interpreter. Served in numerous posts in the Treaty Ports (Tientsin, Ningpo, Hankow, Swatow, Amoy), including Taiwan — the China Coast In Amoy involved in setting up the Freemasons Lodge 1892-1893: retired to Britain 1897: became Professor of Chinese (successor to Thomas Wade) at Cambridge until 1928 His children: Bertram, Valentine, Lancelot, Edith, Mable, and Lionel Giles. Publications A Chinese-English dictionary (1892); a Biographical Dictionary (1898); a Glossary of Reference (1878); complete translation of Zhuangzi 莊子 — Chuang-Tzu, Mystic, Moralist and Social Reformer (1889) Anthologies of Verse and Prose (1923) Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio 聊齋志異, 1880, revised 1908, 1916, 1925. -

The Interaction Between Ethnic Relations and State Power: a Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Dissertations Department of Sociology 5-27-2008 The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911 Wei Li Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Wei, "The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss/33 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INTERACTION BETWEEN ETHNIC RELATIONS AND STATE POWER: A STRUCTURAL IMPEDIMENT TO THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF CHINA, 1850-1911 by WEI LI Under the Direction of Toshi Kii ABSTRACT The case of late Qing China is of great importance to theories of economic development. This study examines the question of why China’s industrialization was slow between 1865 and 1895 as compared to contemporary Japan’s. Industrialization is measured on four dimensions: sea transport, railway, communications, and the cotton textile industry. I trace the difference between China’s and Japan’s industrialization to government leadership, which includes three aspects: direct governmental investment, government policies at the macro-level, and specific measures and actions to assist selected companies and industries. -

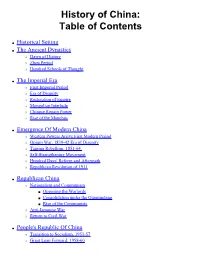

History of China: Table of Contents

History of China: Table of Contents ● Historical Setting ● The Ancient Dynasties ❍ Dawn of History ❍ Zhou Period ❍ Hundred Schools of Thought ● The Imperial Era ❍ First Imperial Period ❍ Era of Disunity ❍ Restoration of Empire ❍ Mongolian Interlude ❍ Chinese Regain Power ❍ Rise of the Manchus ● Emergence Of Modern China ❍ Western Powers Arrive First Modern Period ❍ Opium War, 1839-42 Era of Disunity ❍ Taiping Rebellion, 1851-64 ❍ Self-Strengthening Movement ❍ Hundred Days' Reform and Aftermath ❍ Republican Revolution of 1911 ● Republican China ❍ Nationalism and Communism ■ Opposing the Warlords ■ Consolidation under the Guomindang ■ Rise of the Communists ❍ Anti-Japanese War ❍ Return to Civil War ● People's Republic Of China ❍ Transition to Socialism, 1953-57 ❍ Great Leap Forward, 1958-60 ❍ Readjustment and Recovery, 1961-65 ❍ Cultural Revolution Decade, 1966-76 ■ Militant Phase, 1966-68 ■ Ninth National Party Congress to the Demise of Lin Biao, 1969-71 ■ End of the Era of Mao Zedong, 1972-76 ❍ Post-Mao Period, 1976-78 ❍ China and the Four Modernizations, 1979-82 ❍ Reforms, 1980-88 ● References for History of China [ History of China ] [ Timeline ] Historical Setting The History Of China, as documented in ancient writings, dates back some 3,300 years. Modern archaeological studies provide evidence of still more ancient origins in a culture that flourished between 2500 and 2000 B.C. in what is now central China and the lower Huang He ( orYellow River) Valley of north China. Centuries of migration, amalgamation, and development brought about a distinctive system of writing, philosophy, art, and political organization that came to be recognizable as Chinese civilization. What makes the civilization unique in world history is its continuity through over 4,000 years to the present century. -

Y Chromosome of Aisin Gioro, the Imperial House of Qing Dynasty

Y Chromosome of Aisin Gioro, the Imperial House of Qing Dynasty YAN Shi1*, TACHIBANA Harumasa2, WEI Lan‐Hai1, YU Ge1, WEN Shao‐Qing1, WANG Chuan‐Chao1 1 Ministry of Education Key Laboratory of Contemporary Anthropology and State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering, Collaborative Innovation Center for Genetics and Development, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, Shanghai 200438, China 2 Pen name * Please contact [email protected] Abstract House of Aisin Gioro is the imperial family of the last dynasty in Chinese history – Qing Dynasty (1644 – 1911). Aisin Gioro family originated from Jurchen tribes and developed the Manchu people before they conquered China. By investigating the Y chromosomal short tandem repeats (STRs) of 7 modern male individuals who claim belonging to Aisin Gioro family (in which 3 have full records of pedigree), we found that 3 of them (in which 2 keep full pedigree, whose most recent common ancestor is Nurgaci) shows very close relationship (1 – 2 steps of difference in 17 STR) and the haplotype is rare. We therefore conclude that this haplotype is the Y chromosome of the House of Aisin Gioro. Further tests of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) indicates that they belong to Haplogroup C3b2b1*‐M401(xF5483), although their Y‐STR results are distant to the “star cluster”, which also belongs to the same haplogroup. This study forms the base for the pedigree research of the imperial family of Qing Dynasty by means of genetics. Keywords: Y chromosome, paternal lineage, pedigree, family history, haplogroup, Qing Dynasty This research was supported by the grants from the National Science Foundation of China (31271338), and from Ministry of Education (311016). -

Bridled Tigers: the Military at Korea's Northern Border, 1800–1863

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Bridled Tigers: The Military At Korea’s Northern Border, 1800–1863 Alexander Thomas Martin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Alexander Thomas, "Bridled Tigers: The Military At Korea’s Northern Border, 1800–1863" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3499. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3499 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3499 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bridled Tigers: The Military At Korea’s Northern Border, 1800–1863 Abstract The border, in late Chosŏn rhetoric, was an area of pernicious wickedness; living near the border made the people susceptible to corruption and violence. For Chosŏn ministers in the nineteenth century, despite two hundred years of peace, the threat remained. At the same time, the military institutions created to contain it were failing. For much of the late Chosŏn the site of greatest concern was the northern border in P’yŏngan and Hamgyŏng provinces, as this area was the site of the largest rebellion and most foreign incursions in the first half of the nineteenth century. This study takes the northern border as the most fruitful area for an inquiry into the Chosŏn dynasty’s conceptions of and efforts at border defense. Using government records, reports from local officials, literati writings, and local gazetteers, this study provides a multifaceted image of the border and Chosŏn policies to control it. This study reveals that Chosŏn Korea’s concept of border defense prioritized containment over confrontation, and that their policies were successful in managing the border until the arrival of Western imperial powers whose invasions upended Chosŏn leaders’ notions of national defense.