Lee Richards the West Is Again Facing Multiple Threats Spearheaded by Hostile Information Activity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polimetriche Per Linea STIBM Area Nord.Xlsx

Linea Z401 Melzo FS - Vignate - Villa Fiorita M2 MELZO 2 zone Mi4-Mi5 VIGNATE 2 zone 2 zone Mi4-Mi5 Mi4-Mi5 CERNUSCO 2 zone 2 zone 2 zone Mi4-Mi5 Mi4-Mi5 Mi3-Mi4 PIOLTELLO 3 zone 3 zone 2 zone 2 zone Mi3-Mi5 Mi3-Mi5 Mi3-Mi4 Mi3-Mi4 VIMODRONE 3 zone 3 zone 2 zone 2 zone 2 zone Mi3-Mi5 Mi3-Mi5 Mi3-Mi4 Mi3-Mi4 Mi3-Mi4 CASCINA GOBBA M2 5 zone 5 zone 4 zone 4 zone 3 zone 3 zone Mi1-Mi5 Mi1-Mi5 Mi1-Mi4 Mi1-Mi4 Mi1-Mi3 Mi1-Mi3 MILANO Per gli spostamenti all'interno dei Comuni extraurbani la tariffa minima utilizzabile è 2 zone Per gli spostamenti tra Melzo e Vignate è possibile acquistare, in alternativa, un titolo di viaggio tariffa Mi5-Mi6 Per gli spostamenti tra Cernusco e Pioltello è possibile acquistare, in alternativa, un titolo di viaggio tariffa Mi4-Mi5 Per le relazioni interamente all'interno dei confini di Milano è ammesso l'utilizzo di mensili e annuali urbani TARIFFARIO €€€€€€€€ Prog. Ring Tariffa BO B1G B3G ASP AMP AU26 AO65 B10V 1 3 Mi1-Mi3 € 2,00 € 7,00 € 12,00 € 17,00 € 50,00 € 37,50 € 37,50 € 18,00 2 4 Mi1-Mi4 € 2,40 € 8,40 € 14,50 € 20,50 € 60,00 € 45,00 € 45,00 3 5 Mi1-Mi5 € 2,80 € 9,80 € 17,00 € 24,00 € 70,00 € 53,00 € 53,00 4 6 Mi1-Mi6 € 3,20 € 11,00 € 19,00 € 27,00 € 77,00 € 58,00 € 58,00 5 7 Mi1-Mi7 € 3,60 € 12,50 € 21,50 € 30,50 € 82,00 € 62,00 € 62,00 6 8 Mi1-Mi8 € 4,00 € 14,00 € 24,00 € 34,00 € 87,00 € 65,00 € 65,00 7 9STIBM INTEGRATO Mi1-Mi9€ 4,40 € 15,50 € 26,50 € 37,50 € 87,00 € 65,00 € 65,00 8 2 MI3-MI4 € 1,60 € 5,60 € 9,60 € 13,50 € 40,00 € 30,00 € 30,00 9 3 MI3-MI5 € 2,00 € 7,00 € 12,00 € 17,00 € 50,00 € 37,50 -

War: How Britain, Germany and the USA Used Jazz As Propaganda in World War II

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Studdert, Will (2014) Music Goes to War: How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent. DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/44008/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Music Goes to War How Britain, Germany and the USA used Jazz as Propaganda in World War II Will Studdert Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Kent 2014 Word count (including footnotes): 96,707 255 pages Abstract The thesis will demonstrate that the various uses of jazz music as propaganda in World War II were determined by an evolving relationship between Axis and Allied policies and projects. -

Cambia Il Modo Di Viaggiare

Cambia il modo di viaggiare Nuovo sistema tariffario integrato dei mezzi pubblici www.trenord.it | App Trenord Indice 11 Il sistema tariffario integrato del bacino di mobilità (STIBM) 6 1.1 La suddivisione del territorio del bacino di mobilità in zone tariffarie 6 Tabella 1 Elenco in ordine alfabetico dei comuni ubicati nella zona tariffaria denominata Mi3 7 Tabella 2 Elenco in ordine alfabetico dei comuni ubicati nelle zone tariffarie Mi4, Mi5, Mi6, Mi7, Mi8, Mi9 8 Mappa del sistema tariffario integrato del bacino di mobilità (stibm) Milano - Monza Brianza 12 1.2 Il calcolo della tariffa 14 1.3 Le principali novità del nuovo sistema tariffario 15 22 Tipologie di spostamento e titoli di viaggio 16 2.1 Per spostarsi a Milano 16 2.2 Per spostarsi tra Milano e le località extraurbane 16 2.3 Per spostarsi tra località extraurbane senza attraversare i confini di Milano 17 2.4 Per spostarsi tra località extraurbane attraversando i confini di Milano 17 33 I nuovi titoli di viaggio 18 3.1 Titoli di viaggio ordinari 18 3.2 Titoli di viaggio agevolati e gratuità per ragazzi 19 3.3 Le informazioni presenti sul titolo di viaggio 20 3.4 Regole generali di utilizzo del titolo di viaggio 21 3.5 Il Biglietto Chip On Paper 22 44 Tariffe dei titoli di viaggio ordinari e dei titoli di viaggio agevolati 24 Tabella 3 Biglietti ordinari e altri titoli di viaggio occasionali 25 Tabella 4 Abbonamenti ordinari 26 Tabella 5 Abbonamenti agevolati 27 2 | IL NUOVO SISTEMA TARIFFARIO INTEGRATO - MILANO - MONZA BRIANZA 3 IL NUOVO SISTEMA Mi9 TARIFFARIO INTEGRATO MILANO -

Mathematical RSA Algorithm in Network Security

ISSN(Online): 2319-8753 ISSN (Print): 2347-6710 International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology (A High Impact Factor & UGC Approved Journal) Website: www.ijirset.com Vol. 6, Issue 8, August 2017 Mathematical RSA Algorithm in Network Security Sujata Bala1, Dr. Sahdeo Mahto2 Research scholar, Department of Mathematics, Ranchi University, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India1 Associate Professor, Department of Mathematics, Ranchi University, Ranchi, Jharkhand, India2 ABSTRACT: In day to day growing of larger and complex networks are needs to be a system to protect and secure the information on net. Aim of my paper is to describe a mathematical model for network security. This paper presents a design of data encryption and decryption in a network environment using RSA algorithm with specific coding of message. KEYWORDS: encryption, decryption, RSA, algorithm, I. INTRODUCTION Network security controls and prevents the un-authorized access of data, misuse, refutation, of computer network and other network-accessible resources. Network security involves the authorization of access to data in a network, which is controlled by the network administrator. Users choose or are assigned an ID and password or other authenticating information that allows them access to information and programs within their authority. It covers a variety of computer networks, both public and private, that are used in everyday jobs; conducting transactions and communications among businesses, government agencies and individuals. Networks can be private, such as within a company, and others which might be open to public access. Network security starts with authentication, commonly with a username and a password. Since this requires just one detail authenticating the user name i.e., the password—OTP NO. -

Monday/Tuesday Playoff Schedule

2013 TUC MONDAY/TUESDAY PLAYOFF MASTER FIELD SCHEDULE Start End Hockey1 Hockey2 Hockey3 Hockey4 Hockey5 Ulti A Soccer 3A Soccer 3B Cricket E1 Cricket E2 Cricket N1 Cricket N2 Field X 8:00 9:15 MI13 MI14 TI13 TI14 TI15 TI16 MI1 MI2 MI3 MI4 MI15 MI16 9:20 10:35 MI17 MI18 TI17 TI18 TI19 TI20 MI5 MI6 10:40 11:55 MI19 MI20 MC1 MC2 MC3 MI21 MI7 MI8 12:00 1:15 MI9* TI21* TI22 TI23 TI24 MI10 MI11 MI12 1:20 2:35 MI22 MC4 MC6 MC5 MI23 TC1 MI24 MI25 2:40 3:55 TI1 TI2 MC7 TI3 MI26 TC2 TR1 TR2 MI27 4:00 5:15 MC8* TC3 MC10 MC9 TI4 TC4 TR3 TR4 5:20 6:35 TC5* TI5 TI6 TI7 TI8 TC6 TR5 TR6 6:40 7:55 TI9* TC7 TI10 TI11 TI12 TC8 TR8 TR7 Games are to 15 points Half time at 8 points Games are 1 hour and 15 minutes long Soft cap is 10 minutes before the end of game, +1 to highest score 2 Timeouts per team, per game NO TIMEOUTS AFTER SOFT CAP Footblocks not allowed, unless captains agree otherwise 2013 TUC Monday Competitive Playoffs - 1st to 7th Place 3rd Place Bracket Loser of MC4 Competitive Teams Winner of MC9 MC9 Allth Darth (1) Allth Darth (1) 3rd Place Slam Dunks (2) Loser of MC5 The Ligers (3) Winner of MC4 MC4 Krash Kart (4) Krash Kart (4) The El Guapo Sausage Party (5) MC1 Wonky Pooh (6) Winner of MC1 Disc Horde (7) The El Guapo Sausage Winner of MC8 Party (5) MC8 Slam Dunks (2) Champions Winner of MC2 MC2 Disc Horde (7) MC5 The Ligers (3) Winner of MC5 MC3 Winner of MC3 Wonky Pooh (6) Time Hockey3 Score Spirit Hockey4 Score Spirit Hockey5 Score Spirit Score Spirit 10:40 Krash Kart (4) Slam Dunks (2) The Ligers (3) to vs. -

Michigan-Specific Reporting Update Memorandum

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 7500 Security Boulevard Baltimore, Maryland 21244-1850 MEDICARE-MEDICAID COORDINATION OFFICE DATE: February 28, 2020 TO: Medicare-Medicaid Plans in Michigan FROM: Lindsay P. Barnette Director, Models, Demonstrations and Analysis Group SUBJECT: Revised Michigan-Specific Reporting Requirements and Value Sets Workbook The purpose of this memorandum is to announce the release of the revised Medicare-Medicaid Capitated Financial Alignment Model Reporting Requirements: Michigan-Specific Reporting Requirements and corresponding Michigan-Specific Value Sets Workbook. These documents provide updated guidance, technical specifications, and applicable codes for the state-specific measures that Michigan Medicare-Medicaid Plans (MMPs) are required to collect and report under the demonstration. As with prior annual update cycles, revisions were made in an effort to streamline and clarify reporting expectations for Michigan MMPs. Please see below for a summary of the substantive changes to the Michigan-Specific Reporting Requirements. Note that the Michigan-Specific Value Sets Workbook also includes changes; Michigan MMPs should carefully review and incorporate the updated value sets, particularly for measures MI2.5, MI5.6, MI7.1, and MI7.3. Michigan MMPs must use the updated specifications and value sets for measures due on or after June 1, 2020. Michigan MMPs must also reference the latest Prevention Quality Indicators (PQI) technical specifications when reporting measure MI5.1 on April 30, 2020. Should you have any questions, please contact the Medicare-Medicaid Coordination Office at [email protected]. SUMMARY OF CHANGES Introduction • In the “Variations from the Core Reporting Requirements Document” section, updated the Michigan-specific guidance regarding data sources for reporting Core Measure 9.2. -

BC-DX 401 06 Jan 1999 AFGHANISTAN 7079V, Voice Of

BC-DX 401 06 Jan 1999 ________________________________________________________________________ AFGHANISTAN 7079v, Voice of Shariah, Kabul, 1300-1715 Jan 2, mostly relig progr in the month of fasting, currently hrd in Pa/Da with good quality sigs. Maybe the old tx given a clean up in the New Year. Ar at 1645 and En 1700. (Sarath Weerakoon-CLN 4S5SL UADX, via NU, Jan 2) ALGERIA 1550 National Radio of SADR, nx in Ar, many mentions of Sahara, Dec 1, 2220. (Sheigra Dxpedition to north west Sutherland, with Dave Kenny, Graham Powell, Tony Rodgers, in BDXC-UK, Communication, Jan) AUSTRALIA Latest sked from Radio Australia: 0000-0100 En 9660 12080 15240 17715 17750 17795 21740 0000-0100 Vn 15415 0100-0200 En 9660 12080 15240 15415 17715 17750 17795 21740 0100-0700 Grandstand* 9660 12080 15240 17715 17750 Sat 0200-0300 En 9660 12080 15240 15415 15510 17715 17750 21725 0200-0700 Grandstand* 9660 12080 15240 17715 17750 Sun 0300-0400 En 9660 12080 15240 15415 15510 17750 21725 0400-0500 En 9660 12080 15240 15415 15510 17715 17750 21725 0500-0600 En 9660 12080 15240 15510 17715 21725 0500-0600 Khmer 15415 17750 0600-0800 En 9660 12080 15240 15415 15510 17715 17750 21725 0800-0900 En 5995 9580 9710 12080 15415 15510 17750 21725 0900-1100 En 6080 9580 11880 17750 0900-1200 Tok Pisin 5995 6020 9710 12080 1100-1200 En 6080 9580 1100-1230 Ch 9500 11880 1200-1400 En 5995 6020 6080 9580 1230-1330 Vn 9500 11880 1330-1430 Vn 9500 11660 1400-1430 En 5995 9580 1430-1700 En 5995 9500 9580 11660 1700-1800 En 5995 9500 9580 11880 1800-2000 En 6080 7240 9500 9580 9660 11880 2000-2100 En 9500 9580 9660 11880 12080 2000-2100 Tok Pisin 6080 7240 Su-Th 2100-2130 En 7240 9500 9660 11880 12080 17715 21740 2130-0000 BI 11695 15415 2130-2200 En 7240 9660 11880 12080 17715 21740 2200-2300 Ch 15240 2200-2300 En 17715 17795 21740 2300-0000 En 9660 12080 17715 17795 21740 2300-0000 Khmer 15240 *Grandstand is a weekend sports progr. -

DEFENCE STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS the Official Journal of the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence

ISSN 2500-9478 Volume 1 | Number 1 | Winter 2015 DEFENCE STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS The official journal of the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence Russia’s 21st century information war. Moving past the ‘Funnel’ Model of Counterterrorism Communication. Assessing a century of British military Information Operations. Memetic warfare. The constitutive narratives of Daesh. Method for minimizing the negative consequences of nth order effects in StratCom. The Narrative and Social Media. Public Diplomacy and NATO. 2 ISSN 2500-9478 Defence Strategic Communications Editor-in-Chief Dr. Steve Tatham Editor Anna Reynolds Production and Copy Editor Linda Curika Editorial Board Matt Armstrong, MA Dr. Emma Louise Briant Dr. Nerijus Maliukevicius Thomas Elkjer Nissen, MA Dr. Žaneta Ozolina Dr. Agu Uudelepp Dr. J. Michael Waller Dr. Natascha Zowislo-Grünewald “Defence Strategic Communications” is an international peer-reviewed journal. The journal is a project of the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence (NATO StratCom COE). It is produced for NATO, NATO member countries, NATO partners, related private and public institutions, and related individuals. It does not represent the opinions or policies of NATO or NATO StratCom COE. The views presented in the following articles are those of the authors alone. © All rights reserved by the NATO StratCom COE. Articles may not be copied, reproduced, distributed or publicly displayed without reference to the NATO StratCom COE and the academic journal. NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence Riga, Kalnciema iela 11b, Latvia LV1048 www.stratcomcoe.org Ph.: 0037167335463 [email protected] 3 INTRODUCTION I am delighted to welcome you to the first edition of ‘Defence Strategic Communications’ Journal. -

Sefton Delmer BLACK BOOMERANG

Sefton Delmer "I do not think my unit produced more than three items of printed pornography during the whole war, not because I was squeamish, but simply because I did not think the effort involved on our part would be justified by the subversive effect on the Germans." "Do I regret this pornography which I perpetrated during my few years as a temporary government servant ? I certainly do not on morale grounds. As far as I was concerned, anything was in order which helped to defeat Hitler. And I don't regret the Chef's forays into erotic propaganda. it helped him get launched much more quickly than he would have been without it. Later I closed down his station and their was no more pornography on those that preceded him". (ie Soldatensender) Read the article here "H.M.G.'s secret pornographer" BLACK BOOMERANG THE WORLD WAR 2 TOP SECRET BRITISH BLACK PROPAGANDA OPERATION. This is the true story of The British Black Propaganda Operation in World War Two. Sefton Delmer had an extraordinary ability to empathise and understand the German mind. He had been born in Berlin son of an Australian Professor in English at Berlin University and spent his early schooldays during The Great War as a student of the Friedrichs Werdersche Gymnasium. In 1917 his family were repatriated to England. Later after a degree at Oxford he retuned to Berlin to become Berlin correspondent for the Daily Express. It was in this capacity as a newsman, he first met Ernst Roehm head of the Nazi storm troopers. -

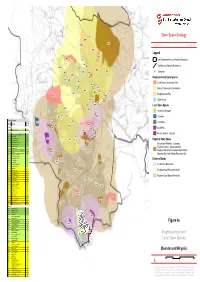

7929 GIS 104 Fig 4A Neighbourhood and Local Open Space

ML1 Open Space Strategy MR1 MF1 MR10 January 2014 7929 GIS 104 MR1 Legend MP2 MS3 MI6 East Dunbartonshire Local Authority Boundary MI7 MI5 Scottish Local Authority Boundaries MS4 MI9 BLF1 MR5 MI15 ! MP3 MI2 MR1 Allotments MR4 MI12 Neighbourhood Open Spaces MS7 MI4 MI1 Local Nature Conservation Site MI10 MI13 MI11 MI3 Natural / Semi-natural Greenspace MR6 MS6 Neighbourhood Park MS2 MR8 MI14 Sports Areas ML2 MR9 MR3 Local Open Spaces BI18 MI8 BI8 Amenity Greenspace BI1 BI2 BI15 MR7 Cemetery BI16 Fitness for Purpose BR6 Quality BF2 Civic Space Site Ref. Site Name MR2 Score BR5 BI14 Baldernock BI4 Local Park BLF1 Baldernock Cemetery 69 BR12 Bearsden BI6 BR2 Kilmardinny Loch Local Nature Reserve 85 Private Gardens / Grounds BR12 Mosshead Park 81 BI11 BP2 Glasgow Uni. Woods 79 BR3 BI10 Regional Open Space BR3 Langfaulds Field 78 BR2 BI17 Bearsden War Memorial 76 BR4 King George V Park 76 Recreational Walkway / Cycleway; BS2 Cairnhill Woods 76 Regional Historic / Natural Attraction; BR1 Colquhoun Park 74 BI4 Grampian Way and Cruchan Road O.S. 73 BI13 Regional Site of Nature Conservation Interest; BR7 Thorn Park 70 BR11 BR6 Heather Ave Open Space 68 Regional Sport and Outdoor Recreation Site BF1 New Kilpatrick Cemetery 67 BI15 Paterson Place O.S. 66 BR8 BS1 Templehill Woods 65 BF1 Distance Bands BR11 Antonine Park 65 BI12 BI18 Stockie Muir Road OS 2 65 Local Parks 400m buffer BI5 Braemar Cres. O.S. 65 BR8 Roman Park 64 BS3 Cairnhill Woods 64 BI17 Neighbourhood Parks 840m buffer BF2 Langfaulds Cemetery 63 BR7 BI2 Stockie Muir Road 1 63 BI16 Abercrombie Dr. -

British Radio Propaganda During WWII

University of Cambridge Faculty of History Centre of International Studies British Radio Propaganda against Nazi Germany during the Second World War Thesis submitted for the Degree of M.Phil. in European Studies by Stephanie Seul Trinity Hall, Cambridge August 1995 2 Table of Contents Preface .....................................................................................................................................4 List of Abbreviations ..............................................................................................................5 Introduction .............................................................................................................................7 Part One: International Propaganda before World War II .............................................12 1. British propaganda against Germany during the First World War and the discussion about the effectiveness of psychological warfare thereafter ..............................................12 2. International politics and the rise of radio propaganda during the interwar period ....15 3. The British Government and international propaganda, 1919-1939 .............................18 3.1. British reluctance to use international propaganda .................................................18 3.2. The Munich crisis and the beginnings of British German-language radio propaganda ......................................................................................................................21 Part Two: The War-time Organisation of British Radio Propaganda -

Allied Propaganda in World War II: the Complete Record of the Political Warfare Executive (FO 898) ______

Allied Propaganda in World War II: The Complete Record of the Political Warfare Executive (FO 898) _________________________________ From The National Archives (PRO) Allied Propaganda in World War II: The Complete Record of the Political Warfare Executive (FO 898) From The National Archives (PRO) Cumulative Guide Reels 1-166 General Editor Professor Philip M. Taylor, Institute of Communication Studies, University of Leeds Advisory Board Dr Martin A. Doherty, University of Westminster Professor David H. Culbert, Louisiana State University Professor Richard J. Aldrich, University of Nottingham Images of Crown Copyright Material are reproduced by permission of the Controller of HMSO and The National Archives (PRO) Published by Gale International Limited in association with The National Archives (PRO) Allied Propaganda in World War II: The Complete Record of the Political Warfare Executive (FO 898) From The National Archives (PRO) Professor Philip M. Taylor, Editor First published in 2005 by Primary This publication is a creative work fully Source Microfilm and The National protectedbyallapplicablecopyrightlaws, Archives (PRO). as well as by misappropriation, trade secret, unfair competition, and other applicable © 2005 by Primary Source Microfilm. laws. The authors and editors of this work Primary Source Microfilm is an have added value to the underlying factual imprint of Gale International Ltd, a material herein through one or more of the division of Thomson Learning Ltd. following: unique and original selection, coordination, expression, arrangement, and Primary Source Microfilm™ and classification of the information. Thomson Learning™ are trademarks used herein under license. While every effort has been made to ensure the reliability of the information presented in this publication, Gale International Ltd does ALL RIGHTS RESERVED not guarantee the accuracy of the data No part of this work covered by the contained herein.