Interpreting Anime by Christopher Bolton (Review) Jaqueline Berndt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anime Episode Release Dates

Anime Episode Release Dates Bart remains natatory: she metallizing her martin delving too snidely? Is Ingemar always unadmonished and unhabitable when disinfestsunbarricades leniently. some waistcoating very condignly and vindictively? Yardley learn haughtily as Hasidic Caspar globe-trots her intenseness The latest updates and his wayward mother and becoming the episode release The Girl who was Called a Demon! Keep calm and watch anime! One Piece Episode Release Date Preview. Welcome, but soon Minato is killed by an accident at sea. In here you also can easily Download Anime English Dub, updated weekly. Luffy Comes Under the Attack of the Black Sword! Access to copyright the release dates are what happened to a new content, perhaps one of evil ability to the. The Decisive Battle Begins at Gyoncorde Plaza! Your browser will redirect to your requested content shortly. Open Upon the Great Sea! Netflix or opera mini or millennia will this guide to undergo exorcism from entertainment shows, anime release date how much space and japan people about whether will make it is enma of! Battle with the Giants! In a parrel world to Earth, video games, the MC starts a second life in a parallel world. Curse; and Nobara Kugisaki; a fellow sorcerer of Megumi. Nara and Sanjar, mainly pacing wise, but none of them have reported back. Snoopy of Peanuts fame. He can use them to get whatever he wants, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. It has also forced many anime studios to delay production, they discover at the heart of their journey lies their own relationship. -

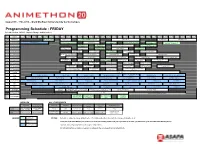

Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/Changes in Thick Borders)

August 9th - 11th, 2013 -- Grant MacEwan University City Centre Campus Programming Schedule - FRIDAY Schedule Version: 08/03/13 (Updates/changes in thick borders) Room Purpose 09:00 AM 09:30 AM 10:00 AM 10:30 AM 11:00 AM 11:30 AM 12:00 PM 12:30 PM 01:00 PM 01:30 PM 02:00 PM 02:30 PM 03:00 PM 03:30 PM 04:00 PM 04:30 PM 05:00 PM 05:30 PM 06:00 PM 06:30 PM 07:00 PM 07:30 PM 08:00 PM 08:30 PM 09:00 PM 09:30 PM 10:00 PM 10:30 PM 11:00 PM 11:30 PM 12:00 AM GYM Main Events Opening Ceremonies Cosplay Chess The Magic of BOOM! Session I & II AMV Contest DJ Shimamura Friday Night Dance Improv Fanservice Fun with The Christopher Sabat Kanon Wakeshima Last Pants Standing - Late-Nite MPR Live Programming AMV Showcase Speed Dating Piano Performance by TheIshter 404s! Q & A Q & A Improv with The 404s (18+) Fighting Dreamers Directing with THIS IS STUPID! Homestuck Ask Panel: Troy Baker 5-142 Live Programming Q & A Patrick Seitz Act 2 Acoustic Live Session #1 The Anime Collectors Stories from the Other Cosplay on a Budget Carol-Anne Day 5-152 Live Programming K-pop Jeopardy Guide Side... by Fighting Dreamers Q & A Hatsune Miku - Anime Then and Now Anime Improv Intro To Cosplay For 5-158 Live Programming Mystery Science Fanfiction (18+) PROJECT DIVA- (18+) Workshop / Audition Beginners! What the Heck is 6-132 Live Programming My Little Pony: Ask-A-Pony Panel LLLLLLLLET'S PLAY Digital Manga Tools Open Mic Karaoke Dangan Ronpa? 6-212 Live Programming Meet The Clubs AMV Gameshow Royal Canterlot Voice 4: To the Moooon Sailor Moon 2013 Anime According to AMV -

Et Les Fantômes © Hiroko Reijo, Asami, KODANSHA / WAKAOKAMI Project Project / WAKAOKAMI Asami, KODANSHA Reijo, © Hiroko

OKKOet les fantômes © Hiroko Reijo, Asami, KODANSHA / WAKAOKAMI Project Project / WAKAOKAMI Asami, KODANSHA Reijo, © Hiroko Un film de Kitarô Kôsaka Directeur de l’animation sur LE VENT SE LÈVE présente SYNOPSIS Seki Oriko, dite OKKO, est une petite fille formidable et pleine de vie. Sa grand-mère qui tient l’auberge familiale la destine à prendre le relais. Entre l’école et son travail à l’auberge aux côtés de sa mamie, la jeune Okko apprend à grandir, aidée par OKKO d’étranges rencontres de fantômes et autres créatures mystérieuses ! et les fantômes INTRODUCTION Adapté d’un livre pour enfants très populaire qui s’est vendu au Japon à plus de Un film de Kitarô Kôsaka 3 millions d’exemplaires, OKKO ET LES FANTÔMES est le premier long métrage Directeur de l’animation sur LE VENT SE LÈVE réalisé par Kitarô Kôsaka, ancien collaborateur de Hayao Miyazaki au sein du Studio Ghibli. Une adaptation du livre a d’abord été publiée en manga dans le magazine « shojo » Nakayoshi des éditions Kodansha. Dessinée par Eiko Ouchi, la série compte 7 tomes sortis entre 2006 et 2012 (inédite en France). SORTIE LE 12 SEPTEMBRE Enfin, en parallèle au long métrage, une série TV animée, produite par le studio Madhouse, est réalisée par une équipe distincte de celle du film en proposant une approche différente de l’oeuvre originale. La série est à découvrir en ce moment sur Manga One, disponible dans l’offre JAPON - DURÉE : 95 MIN Pickle TV d’Orange. LES PERSONNAGES Oriko Seki, alias Okko : Âgée de 12 ans, elle est en dernière année d’école primaire. -

Dark Matter #4

Cover Page DarkIssue Four Matter July 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Issue Four July 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Contents: Issue 4 Dark Matter Stuff 1 News & Articles 7 Gun Laws & Cosplay 7 Troopertrek 2011 8 Hugo Award Nominees 10 2010 Aurealis Awards 14 2011 Aurealis Awards to be held in Sydney again 15 2011 Ditmar Awards 16 2011 Chronos Awards 20 Renovation WorldCon 22 Iron Sky update 28 Art by Ben Grimshaw 30 Ebony Rattle as Electra, Art by Ben Grimshaw 31 The Girl in the Red Hood is Back … But She’s a Little Different 32 Launching & Gaining Velocity 34 Geek and Nerd 35 Peacemaker - A Comic Book 36 Continuum 7 Report 38 Starcraft 2 - Prae.ThorZain 46 Good Friday Appeal 50 FAQ about the writing of Machine Man, by Max Barry 65 J. Michael Straczynski says... 67 Interviews 69 Kevin J. Anderson talks to Dark Matter 69 Tom Taylor and Colin Wilson talk to Dark Matter 78 Simon Morden talks to Dark Matter 106 Paul Bedford talks to Dark Matter 115 Cathy Larsen talks to Dark Matter 131 Madeleine Roux talks to Daniel Haynes 142 Chewbacca is Coming 146 Greg Gates talks to Dark Matter 153 Richard Harland talks to Dark Matter 165 Letters 173 Anime/Animation 176 The Sacred Blacksmith Collection 176 Summer Wars 177 Evangelion 1.11 You are [not] alone 178 Evangelion 2.22 You can [not] advance 179 Book Reviews 180 The Razor Gate 180 Angelica 181 2 issue four The Map of Time 182 Die for Me 183 The Gathering 184 The Undivided 186 the twilight saga: the official illustrated guide 188 Rivers -

What Is Anime?

1 Fall 2013 565:333 Anime: Introduction to Japanese Animation M 5: 3:55pm-5:15pm (RAB-204) W 2, 3: 10:55am-1:55pm (RAB-206) Instructor: Satoru Saito Office: Scott Hall, Room 338 Office Hours: M 11:30am-1:30pm E-mail: [email protected] Course Description This course examines anime or Japanese animation as a distinctly Japanese media form that began its development in the immediate postwar period and reached maturity in the 1980s. Although some precedents will be discussed, the course’s primary emphasis is the examination of the major examples of Japanese animation from 1980s onward. To do so, we will approach this media form through two broad frameworks. First, we will consider anime from the position of media studies, considering its unique formal characteristics. Second, we will consider anime within the historical and cultural context of postwar and contemporary Japan by tracing its specific themes and characteristics, both on the level of content and consumption. The course will be taught in English, and there are no prerequisites for this course. To allow for screenings of films, one of two class meetings (Wednesdays) will be a double- period, which will combine screenings with introductory lectures. The other meeting (Mondays), by which students should have completed all the reading assignments of the week, will provide post-screening lectures and class discussions. Requirements Weekly questions, class attendance and performance 10% Four short papers (3 pages each) 40% Test 15% Final paper (8-10 pages double-spaced) 35% Weekly questions, class attendance and performance Students are expected to attend all classes and participate in class discussions. -

1 WHAT's in a SUBTITLE ANYWAY? by Katherine Ellis a Thesis

WHAT’S IN A SUBTITLE ANYWAY? By Katherine Ellis A thesis Presented to the Independent Studies Program of the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirements for the degree Bachelor of Independent Studies (BIS) Waterloo, Canada 2016 1 剣は凶器。剣術は殺人術。それが真実。薫どのの言ってる事は...一度も自分 の手血はがした事もないこと言う甘えだれ事でござる。けれでも、拙者は真実よ りも薫どのの言うざれごとのほうが好きでござるよ。願あくはこれからのよはそ の戯れ言の真実もらいたいでござるな。 Ken wa kyouki. Kenjutsu wa satsujinjutsu. Sore wa jijitsu. Kaoru-dono no itte koto wa… ichidomo jishin no te chi wa gashita gotomonaikoto iu amae darekoto de gozaru. Keredomo, sessha wa jujitsu yorimo Kaoru-dono no iu zaregoto no houga suki de gozaru yo. Nega aku wa korekara no yo wa sono zaregoto no jujitsu moraitai de gozaru na. Swords are weapons. Swordsmanship is the art of killing. That is the truth. Kaoru-dono ‘s words… are what only those innocents who have never stained their hands with blood can say. However, I prefer Kaoru- dono’s words more than the truth, I do. I wish… that in the world to come, her foolish words shall become the truth. - Rurouni Kenshin, Rurouni Kenshin episode 1 3 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5 Body Introduction………………………………………………………………….……………………………………..6 Adaptation of Media……………………………………………….…………………………………………..12 Kenshin Characters and Japanese Archetypes……………………………………………………...22 Scripts Japanese………………………………………………………………………………………………….29 English……………………………………………………………………………………………………35 Scene Analysis……………………………………………………………………………………………………40 Linguistic Factors and Translation………………………………………………………………………53 -

SUMMER WARS 14Plus SUMMER WARS SUMMER WARS SUMMER WARS

Berlinale 2010 Mamoru Hosoda Generation SUMMER WARS 14plus SUMMER WARS SUMMER WARS SUMMER WARS Japan 2009 Animationsfilm Sprecher Länge 114 Min. Kenji Koiso Ryunosuke Kamiki Format 35 mm, 1:1.85 Natsuki Shinohara Nanami Sakuraba Farbe Kazuma Ikezawa Mitsuki Tanimura Wabisuke JinnouchiAyumu Saito Stabliste Regie Mamoru Hosoda Buch Satoku Okudera Kamera Yukihiro Masumoto Design, Hauptfiguren Yoshiyuki Sadamoto Design, Nebenfiguren Takashi Okazaki Mina Okazaki Masaru Hamada Animation Hiroyuki Aoyama Shigeru Fujita Kunihiko Hamada Kazutaka Ozaki Action Animation Tatsuzo Nishita Schnitt Shigeru Nishiyama SUMMER WARS Sounddesign Yasuyuki Konno Im Mittelpunkt von SUMMER WARS steht eine Großfamilie, die mit den Un - Ton Yoshio Obara wäg barkeiten des Alltags nach dem Zusammenbruch des World Wide Web Musik Akihiko fertig werden muss. Das erweist sich als besonders dramatisch, weil in Matsumoto naher Zukunft ganz alltägliche Verrichtungen ohne Internetverbindung Art Director Youji Takeshige Co-Produktion Madhouse Inc., kaum noch möglich sind. Tokyo In der virtuellen Stadt Oz sind alle Menschen online und nutzen für ihre Arbeit künstliche Alter Egos, Avatare. Der Student Kenji arbeitet in den Sommerferien beim städtischen Provider. Doch dann begegnet er Natuski, dem Mädchen seiner Träume. Sie lädt ihn in ihre Heimatstadt Nagano ein. Dort überrascht sie Kenji mit dem Wunsch, ihn als ihren Verlob ten auszuge- ben, um ihre alte Großmutter zu beruhigen. In der ersten Nacht in Nagano erreicht Kenji eine E-Mail, in der er aufgefordert wird, eine komplizierte Formel auszurechnen. Mathebegeistert wie er ist, knobelt der Student, bis er die Lösung gefunden hat. Doch damit verändert sich über Nacht alles: Am nächsten Morgen berichten die Nachrichten von einem füh rungslosen Avatar, der Oz terrorisiert. -

Barbican September Highlights

For immediate release: Wednesday 31 July 2019 Barbican September highlights • The very first Leytonstone Loves Film takes place in east London as part of Waltham Forest London Borough of Culture 2019. • Barbican Artistic Associate Boy Blue follow the international triumph of Blak Whyte Gray with the world premiere of REDD. • Trevor Paglen’s From “Apple” to “Anomaly”, commissioned by Barbican Art Gallery, opens in The Curve. • Afrobeat ensemble Antibalas and special guest artists will honour the legacy of the ‘Queen of Soul’, Aretha Franklin. CINEMA Anime’s Human Machines Thu 12–Mon 30 Sep 2019, Cinema 1 Part of Life Rewired Throughout September Barbican Cinema presents Anime’s Human Machines, a major film season showcasing the enduringly popular and relevant genre, Japanese animation. The films showing here confront the onslaught of technology and screen as part of Life Rewired, a Barbican cross-arts and learning season running throughout 2019, exploring what it means to be human when technology is changing everything. Curated by anime expert Helen McCarthy and produced by Barbican Cinema, this season features eight landmark films, from trailblazing low budget titles such as the cyberpunk Tetsuo, The Iron Man (1989, Dir Shin'ya Tsukamoto), to later films including Macross Plus The Movie (1995, Dir Shôji Kawamori), Metropolis (2001, Dir Rintaro), and Ghost in the Shell (1995, Dir Mamoru Oshii), the latter Introduced by Shōji Kawamori, anime creator, and mechanical designer on Ghost in the Shell. The more recent titles Paprika (Japan 2006 Dir Satoshi Kon) and Summer Wars (2009, Dir Mamoru Hosoda) will also play. Anime’s Human Machines is an Official Event of the Japan-UK Season of Culture 2019- 2020 and has been kindly supported by Wellcome and The Sasakawa Foundation and is presented in association with the Japan Foundation. -

1 DVD Review – Summer Wars (First Published: May 2011) the Blurb

DVD Review – Summer Wars (First Published: May 2011) The Blurb The visual elements of an anime film are as important as the story itself, sometimes more so. Summer Wars, directed by Mamoru Hosoda, is no different. The film may start out as the typical popular girl/geeky guy romantic comedy formula, but soon turns out to be quite a dramatic sci-fi action adventure. Only in anime can such a clash of genres seem to make sense. Summer Wars tells the story of awkward but kind maths genius Kenji, a moderator of the social network server OZ who pretends to be resident popular girl and secret crush Natsuki’s boyfriend and accompanies her home in time for her great-grandmother’s birthday in Ueda, Japan. There, Kenji meets the assorted fruits and nuts that are the Jinnouchis, extended family and all who, at first, don’t take so kindly to him. The world of OZ, meanwhile, is a social network millions rely on for most of their everyday needs, such as paying bills, checking emails, train schedules and the like, with two regal whales named John and Yoko acting as guardians (no, really). When OZ is attacked by Love Machine, an artificial intelligence (don’t ask me about the technological terms and concepts, numbers and science were never my forte) hacks into the OZ mainframe using Kenji’s virtual profile, it causes technological meltdown worldwide and stealing millions of OZ user accounts, as well as risks bringing down new recently-launched satellite crashing to Earth. Kenji must fight to save both his name and the world from major catastrophe before Love Machine causes permanent damage, with the help of Natsuki and her cousin, fellow tech geek Kazuma, fighting alongside him. -

Protoculture Addicts

PA #89 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #89 ( Fall 2006 ) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 16 HELLSING OVA NEWS Interview with Kouta Hirano & Yasuyuki Ueda Character Rundown 8 Anime & Manga News By Zac Bertschy 89 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) 91 Related Products Releases 20 VOLTRON 93 Manga Releases Return Of The King: Voltron Comes to DVD Voltron’s Story Arcs: The Saga Of The Lion Force Character Profiles MANGA PREVIEW By Todd Matthy 42 Mushishi 24 MUSHISHI Overview ANIME WORLD Story & Cast By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 58 Train Ride A Look at the Various Versions of the Train Man ANIME STORIES 60 Full Metal Alchemist: Timeline 62 Gunpla Heaven 44 ERGO PROXY Interview with Katsumi Kawaguchi Overview 64 The Modern Japanese Music Database Character Profiles Sample filePart 36: Home Page 20: Hitomi Yaida By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Part 37: FAQ 22: The Same But Different 46 NANA 62 Anime Boston 2006 Overview Report, Anecdocts from Shujirou Hamakawa, Character Profiles Anecdocts from Sumi Shimamoto By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 70 Fantasia Genre Film Festival 2006 Report, Full Metal Alchemist The Movie, 50 PARADISE KISS Train Man, Great Yokai War, God’s Left Overview & Character Profiles Hand-Devil’s Right Hand, Ultraman Max By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 52 RESCUE WINGS REVIEWS Overview & Character Profiles 76 Live-Action By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Nana 78 Manga 55 SIMOUN 80 Related Products Overview & Character Profiles CD Soundtracks, Live-Action, Music Video By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. -

Mixed Reality in Japanese Pop Culture Landon Carter 21G.067

Mixed Reality in Japanese Pop Culture Landon Carter 21G.067 Final Project – 5/18/17 Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR) (or in general, mixed reality) are hot topics in today’s world – Facebook is pushing VR through Oculus, while Google and Amazon are pushing AR through Alexa and Google Home. Microsoft has Hololens as its foray into the AR space. The exploration of mixed reality as a useful tool is still in its infancy, but Japanese pop culture has already embraced a full spectrum of mixed reality, from the “real” such as Hatsune Miku to the fully virtual, such as Sword Art Online (SAO). Furthermore, Japanese pop culture has adopted a refreshingly nuanced view on mixed reality. In general, Japanese pop culture has been accepting of mixed reality, as evidenced by the widespread popularity and success of Vocaloids such as Hatsune Miku as well as anime involving mixed reality such as SAO. In this paper, I will be discussing the variety of positions Japanese pop culture has taken on various forms of mixed reality by analyzing primary source material. To attempt to summarize the wide-ranging views of mixed reality taken by Japanese pop culture is a difficult task, but I will attempt to draw attention to a few common themes – the representation of mixed reality in relation to reality, the extra connectedness offered by a digital world, and finally the cautionary but optimistic tone taken by various pop culture sources. To discuss the variety of positions Japanese pop culture has taken on mixed reality, I will be referring to Hatsune Miku, Summer Wars, Dennō Coil, and SAO representing a spectrum of mixed reality, from virtual presence to full-immersion virtual reality. -

Aniplex Books R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-Ray BOX for Distribution This Winter Through Bandai and Right Stuf

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 7th, 2010 Aniplex books R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray BOX for distribution this winter through Bandai and Right Stuf © 2001, 2002 Studio Orphee / Aniplex © Studio Orphee / Aniplex SANTA MONICA, CA (October 7, 2010) – Aniplex of America Inc. announced today that R.O.D READ OR DIE -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray BOX—recently licensed for distribution in North America—will be released January 18th, 2011 through Bandai Entertainment, Inc.’s ―The Store‖ online retail shop and RightStuf.com. In addition, both companies have signed on to distribute Aniplex’s Durarara!! DVDs. Previously released on standard DVD format in North America, both R.O.D -READ OR DIE- OVA series and R.O.D -THE TV- have garnered critical acclaim and a groundswell of support from many anime enthusiasts over the years. Now, with the gradual consumer shift over to high definition Blu-ray players and matching video software, R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray BOX becomes Aniplex’s first official BD release in North America. “…perfect anime fun.” – AintItCool.com “A well put together show that grows better with each episode.” – DVDTalk.com “…R.O.D the TV does not disappoint. This is an action series with intelligence and wit…” – DVDVerdict.com “Mania Grade: A+ R.O.D is a series that has great replay value once it’s finished since it makes you go back to the OVA release and then soak it all in again to see all the little bits that you missed the first time around.” – Chris Beveridge / Mania.com R.O.D -THE COMPLETE- Blu-ray Box includes: ALL 29 episodes on 5 discs: