Hale Village Aspects of Post-Medieval Hale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![11797 Mersey Gateway Regeneration Map Plus[Proof]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5912/11797-mersey-gateway-regeneration-map-plus-proof-245912.webp)

11797 Mersey Gateway Regeneration Map Plus[Proof]

IMPACT AREAS SUMMARY MERSEY GATEWAY 1 West Runcorn Employment Growth Area 6 Southern Widnes 8 Runcorn Old Town Centre plus Gorsey Point LCR Growth Sector Focus: Advanced Manufacturing LCR Growth Sector Focus: Advanced Manufacturing / LCR Growth Sector Focus: Visitor Economy / Financial & Widnes REGENERATION PLAN / Low Carbon Energy Financial & Professional Services Professional Services Waterfront New & Renewed Employment Land: 82 Hectares New & Renewed Employment Land: 12 Hectares New & Renewed Employment Land: 6.3 Hectares Link Key Sites: New Homes: 215 New Homes: 530 • 22 Ha Port Of Runcorn Expansion Land Key Sites: Key Sites: Everite Road Widnes Gorsey Point • 20 Ha Port Of Weston • 5 Ha Moor Lane Roadside Commercial Frontage • Runcorn Station Quarter, 4Ha Mixed Use Retail Employment Gyratory • 30 Ha+ INOVYN World Class Chemical & Energy • 3 Ha Moor Lane / Victoria Road Housing Opportunity Area & Commercial Development Renewal Area Remodelling Hub - Serviced Plots • 4 Ha Ditton Road East Employment Renewal Area • Runcorn Old Town Centre Retail, Leisure & Connectivity Opportunities: Connectivity Opportunities: Commercial Opportunities Widnes Golf Academy 5 • Weston Point Expressway Reconfiguration • Silver Jubilee Bridge Sustainable Transport • Old Town Catchment Residential Opportunities • Rail Freight Connectivity & Sidings Corridor (Victoria Road section) Connectivity Opportunities: 6 • Moor Lane Street Scene Enhancement • Runcorn Station Multi-Modal Passenger 3MG Phase 3 West Widnes Halton Lea Healthy New Town Transport Hub & Improved -

Draft Recommendations on the New Electoral Arrangements for Halton Borough Council

Draft recommendations on the new electoral arrangements for Halton Borough Council Electoral review December 2018 Translations and other formats: To get this report in another language or in a large-print or Braille version, please contact the Local Government Boundary Commission for England at: Tel: 0330 500 1525 Email: [email protected] Licensing: The mapping in this report is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. Licence Number: GD 100049926 2018 Contents Introduction 1 Who we are and what we do 1 What is an electoral review? 1 Why Halton? 2 Our proposals for Halton 2 How will the recommendations affect you? 2 Have your say 3 Review timetable 3 Analysis and draft recommendations 5 Submissions received 5 Electorate figures 5 Number of councillors 6 Ward boundaries consultation 7 Draft recommendations 8 Runcorn central 10 Runcorn east 12 Runcorn west 15 Widnes east 17 Widnes north 19 Widnes west 21 Conclusions 23 Summary of electoral arrangements 23 Have your say 25 Equalities 27 Appendices 28 Appendix A 28 Draft recommendations for Halton Borough Council 28 Appendix B 30 Outline map 30 Appendix C 31 Submissions received 31 Appendix D 32 Glossary and abbreviations 32 Introduction Who we are and what we do 1 The Local Government Boundary Commission for England (LGBCE) is an independent body set up by Parliament.1 We are not part of government or any political party. We are accountable to Parliament through a committee of MPs chaired by the Speaker of the House of Commons. -

HBC Field, Halebank, Widnes PROPOSAL

APPLICATION NO: 11/00269/FULEIA LOCATION: HBC Field, Halebank, Widnes PROPOSAL: Proposed construction of a single rail-served building for storage and distribution purposes (total gross internal area 109,660sqm/use class B8) together with associated infrastructure, parking, open space, landscaping and ancillary development WARD: Ditton PARISH: Halebank Parish Council CASE OFFICER: Glen Henry AGENT(S) / Prologis UK Ltd APPLICANT(S): DEVELOPMENT PLAN ALLOCATION: Employment Land Allocations (E1), New Industrial and Commercial Development (E5), Halton Unitary Development Green Belt (GE1), Plan (2005) Proposed Green Space (GE7), Core Strategy (2013) Core Strategy Policy CS8 DEPARTURE No REPRESENTATIONS: 14 by letter and petition of 546 by way of individually signed standard letter in objection. On-going Correspondence with Halebank Parish Council (detailed in the body of the report). Confirmation has been received from Owners of Linner Farm that “as regards the noise inconvenience we have no objections to any of the work being carried out adjacent to Linner Farm”. RECOMMENDATION: Approve subject to conditions. SITE MAP 1.0 BACKGROUND 1.1 The Site and Surroundings The site is approximately 32 Ha known as HBC Field and identified as site 253 with surrounding land previously defined by the Halton UDP as within the Potential Extent of the Ditton Strategic Rail Freight Park now known as Mersey MultiModal Gateway (3MG). The site is in the western area of the designated 3MG area with the A562 Speke Road and West Coast Main Line to the north, Halebank Road to the south, Halebank residential areas to the east and wider agricultural land and Green Belt to the west. -

Full Consultation Report for IRMP 13

Making Cheshire Safer Integrated Risk Management Plan for 2016/17 Report on public, staff and partner consultation January 2016 IRMP 13 (2016/17) Consultation Report Page 1 of 79 Contents Page 1. Introduction 3 2. Executive summary 4 3. The consultation programme 6 4. Consulting with the public 8 5. Consulting with staff and internal stakeholders 13 6. Consulting with stakeholders 16 7. Feedback, evaluation and communicating outcomes 19 8. Detailed results 21 9. Profile of respondents 30 10. Media relations, press coverage and use of social media 42 Appendices Appendix 1: Annual Report, IRMP Summary, IRMP Survey and Stakeholder Newsletter 44 Appendix 2: Partners and stakeholders communicated with 48 Appendix 3: Public comments 51 Appendix 4: Staff comments 67 Appendix 5: Responses from partners and stakeholders 75 IRMP 13 (2016/17) Consultation Report Page 2 of 79 1. Introduction This report sets out the results of the programme of public, staff and partner consultation on Cheshire Fire Authority’s draft Integrated Risk Management Plan (IRMP) for 2016/17, entitled Making Cheshire Safer. The formal consultation period lasted for 12 weeks between September 28th 2015 and December 28th 2015. The purpose of this report is to enable the Authority to understand levels of support among all groups to the proposals set out in the draft IRMP. This feedback will be among the issues considered by the Fire Authority prior to approval of the final version of the IRMP. This report comprises eleven sections, as follows: An executive summary, which briefly describes the consultation programme, the level of response and the key conclusions which can be drawn from the feedback received An overview of the consultation programme An outline of the methods used when consulting with the public Outlining how the Service consulted with staff and internal stakeholders An overview of the approach taken to consult with partners and external stakeholders A description of the work undertaken to assess and evaluate the consultation against previous consultations. -

Notices and Proceedings

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (NORTH WEST OF ENGLAND) NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2716 PUBLICATION DATE: 25 March 2016 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 15 April 2016 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North West of England) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 08/04/2016 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (North West of England) Suite 4 Stone Cross Place Stone Cross Lane North Golborne Warrington WA3 2SH General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications and requests reflect information provided by applicants. The Traffic Commissioner cannot be held responsible for applications that contain incorrect information. -

Planning Application - Part 1

Planning Application - part 1 A1. Applicant Details Organisation Halton Borough Council . Title Forename Surname Name Mr . Philip . Esseen . A1.1 Address Details Name or flat number Landscape Services . Property number or name Picow Farm Depot . Street Picow Farm Road . Locality . Town Runcorn . County Cheshire . Postal Town . Postcode WA7 4UB . A1.2 Communication Details Nat Code Extn No. Telephone No. 01928583916 . Daytime Telephone No. Fax No. Email Address [email protected] . DX Number . Portal Proposal Ref. No:PP-00218308 Page 1 Planning Portal Planning Application Halton Borough Council A2. Agent Details Organisation TEP . Title Forename Surname Name Ms . Tracy . Pursell . A2.1 Address Details Name or flat number . Property number or name Genesis Centre . Street Birchwood Science Park . Locality . Town Warrrington . County Cheshire . Postal Town . Postcode WA3 7BH . A2.2 Communication Details Nat Code Extn No. Telephone No. 01925844004 . Daytime Telephone No. Fax No. 01925844002 . Email Address [email protected] . DX Number . Portal Proposal Ref. No:PP-00218308 Page 2 Planning Portal Planning Application Halton Borough Council 1. Site Address Details 1.1 Address Details Name or flat number . Property number or name HBC Fields . Street Hale Bank Road . Locality Hale Bank . Town . County Cheshire . Postal Town . Postcode WA8 8NW . UPRN 0 . Location The location is illsutrated on drawing D1058.08.025. The site comprises a number of fields to the north west of Hale Bank. The post code for the site is aaumed based on postcodes for adjacent properties, Eastings and northings are as follows: 348100,384400 . 2. Description of the Proposed Development Development Description Creation of a landscaped open space corridor containing new drawinage waterbodies, footpath cycleways and native planting. -

Cheshire Ancestor Registered Charity: 515168 Society Website

Cheshire AnCestor Registered Charity: 515168 Society website: www.fhsc.org.uk Contents Editorial 2 How to Find New Relatives and get Chairman’s Jottings 3 Hooked on Genealogy in a Year 31 Mobberley Research Centre 5 Spotlight on Parish Chest Membership Issues 10 Settlements and Removals 36 Family History Events 11 Stockport BMDs 38 Family History News 15 DNA and the Grandmother Family History Website News 16 Conundrum 40 Books Worth Reading 19 Certificate Exchange 43 Letters to the Editor 22 Net That Serf (grey pages) 46 Help Wanted or Offered 25 Group Events and Activities 56 Aspects of a Registrar’s Professional New Members (green pages) 66 Life 27 Members’ Interests 71 Cover picture: Over (Winsford), St. Chad. The church is late fifteenth century with a tower added in the early sixteenth century. The chancel was lengthened in 1926. There is a monument to Hugh Starkey who rebuilt the church in 1543. Cheshire AnCestor is published in March, June, September and December (see last page). The opinions expressed in this journal are those of individual authors and do not necessarily represent the views of either the editor or the Society. All advertisements are commercial and not indicative of any endorsement by the Society. No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form whatsoever without the prior written permission of the editor and, where applicable, named authors. The Society accepts no responsibility for any loss suffered directly or indirectly by any reader or purchaser as a result of any advertisement or notice published in this Journal. Please send items for possible publication to the editor: by post or email. -

Halebank a Secure Future 2008-13

APPENDIX 2 Halebank A Secure Future 2008-13 A Business Plan for a Business Improvement District on Halebank Industrial Estate, Widnes, Halton. Draft Version : HALEBANK BUSINESS PLAN V3 Produced by: Halebank Business Steering Group, The Halebank Industrial Business Group is supported by: Halebank – Safe and Secure 2008-13 A Proposal for a Business Improvement District on Halebank Industrial Estate Contents 1.0 Open letter from Chair of the..........................................................4 2.0 Introduction.....................................................................................5 2.1 Halebank ............................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 “Delivering Results on Halebank Industrial Estate” - Our Successes 2004 - 2007 ..... 6 3.0 Business Consultation .......................................................................................................... 8 3.1 1st Stage of Consultation – BID Feasibility Study .......................................................8 3.2 2nd Stage of Consultation - Consultation on the Draft Business Plan.........................8 4.0 The Proposed Business Improvement District.................................9 4.1 Theme One – Safe and Secure ............................................................................................ 11 4.2 Theme Two –Image Enhancement ...................................................................................... 13 4.3 Theme Three – Co-ordinated Industrial Estate.................................................................. -

AREA PANEL for BROADHEATH, DITTON & HOUGH GREEN at A

AREA PANEL FOR BROADHEATH, DITTON & HOUGH GREEN th At a meeting of the Area Panel for Broadheath, Ditton and Hough Green held on 7 November 2002 at Halebank School, Widnes Present: Councillors Osborne (in the Chair), Harris, Wright, K. Morley, Nolan, and Gilligan. Apologies for absence: Councillor McDermott. Also in attendance: A. Hill – Executive Director, Resources and Corporate Services A. McCormick – Housing Manager (Widnes West) A. Grant – Committee Services Manager D. Sutton – Operational Director, Regeneration J. Salt – Divisional Commander – Cheshire Fire Brigade J. Westwood – Neighbourhood Travel Team T. Ward-Dutton – Pride of Place Team 56 Members of the public Action 000. MINUTES The Divisional Commander (Cheshire Fire Brigade) addressed the meeting to reassure the public regarding contingency plans if a fire strike occurred and the services that were offered by Cheshire Fire Service. RESOLVED: That the Minutes of the meeting held on 9 th July 2002 be approved. 000. NEIGHBOURHOOD TRAVEL TEAM At the last meeting, it was reported that funding had been secured for the provision of a Neighbourhood Travel Team. The purpose of the team is to identify, and remove travel barriers for those residents seeking employment or personal development. The leader of the Travel Team, Dr. Julian Westwood gave a presentation relating to the team’s key activities. His presentation outlined: (i) why public transport matters, the effects of poor transport on employment and education; (ii) Halton’s research and what was found; (iii) statistics about the state of the Borough; (iv) the purpose and social aims of the Neighbourhood Travel Team; (v) the way forward; (vi) prospective partners; and (vii) early indicators for success. -

Halebank Industrial Estate

MODERN ON THE INSTRUCTIONS OF WAREHOUSE / STORAGE UNIT TO LET 49,189 SQ FT (4,569.70 SQ M) ENTER HALEBANK INDUSTRIAL ESTATE FOUNDRY LANE WIDNES CHESHIRE WA8 8TZ MODERN WAREHOUSE / STORAGE UNIT HALEBANK INDUSTRIAL ESTATE TO LET 49,189 SQ FT (4,569.70 SQ M) FOUNDRY LANE WIDNES CHESHIRE WA8 8TZ DESCRIPTION SPECIFICATION ACCOMMODATION LOCATION EPC & LEGALS CONTACTS BACK FORWARD DESCRIPTION The premises comprise a modern, steel portal frame warehouse facility with a profile sheet metal clad Externally, the unit benefits from a concrete surfaced loading area to the rear and has a separate roof and profile sheet metal clad walls to an eaves height of 7.61m (25 ft). Loading is provided via tarmacadam surfaced staff car parking area to the front and side of the building. 2no., electrically operated, level access loading doors. To the front of the unit there is two storey office The site is fully fenced and gated, with separate vehicular access points for the car park and yard and welfare accommodation providing offices with male and female WCs at both ground and first areas. floor levels. MODERN WAREHOUSE / STORAGE UNIT HALEBANK INDUSTRIAL ESTATE TO LET 49,189 SQ FT (4,569.70 SQ M) FOUNDRY LANE WIDNES CHESHIRE WA8 8TZ DESCRIPTION SPECIFICATION ACCOMMODATION LOCATION EPC & LEGALS CONTACTS BACK FORWARD SPECIFICATION • 49,189 sq ft (4,569.70 sq m). • Modern warehouse / storage facility with good quality yard space. • Eaves height of 7.61m (25 ft). • Good quality office accommodation. • Fully secure and self-contained site. MODERN WAREHOUSE / STORAGE -

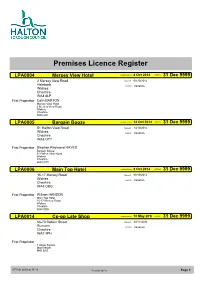

Premises Licence Register

Premises Licence Register LPA0004 Mersey View Hotel commences 8 Oct 2014 expires 31 Dec 9999 2 Mersey View Road issued 08/10/2014 Halebank reason Variation Widnes Cheshire WA8 8LP First Proprietor Colin BARTON Mersey View Hotel 2 Mersey View Road Widnes Cheshire WA8 8LP LPA0005 Bargain Booze commences 14 Oct 2014 expires 31 Dec 9999 51 Halton View Road issued 14/10/2014 Widnes reason Variation Cheshire WA8 OTT First Proprietor Stephen Raymond HAYES Bargain Booze 51 Halton View Road Widnes Cheshire WA8 OTT LPA0006 Main Top Hotel commences 8 Oct 2014 expires 31 Dec 9999 15-17 Mersey Road issued 08/10/2014 Widnes reason Variation Cheshire WA8 OBG First Proprietor William HANSON Main Top Hotel 15-17 Mersey Road Widnes Cheshire WA8 0DG LPA0014 Co-op Late Shop commences 10 May 2018 expires 31 Dec 9999 66-70 Balfour Street issued 24/11/2005 Runcorn reason Variation Cheshire WA7 4PH First Proprietor 1 Angel Square Manchester M60 0AG 07 Feb 2019 at 11:10 Printed by LalPac Page 1 Premises Licence Register LPA0015 Co-op Late Shop commences 12 Jul 2007 expires 31 Dec 9999 7 Grangeway issued 24/11/2005 Town Hall Estate reason Cancel/Surrender Runcorn Cheshire WA7 5LY First Proprietor 1 Angel Square Manchester M60 0AG LPA0016 Co-op Late Shop commences 14 Mar 2018 expires 31 Dec 9999 Windmill Hill Avenue West issued 14/03/2018 Runcorn reason Cheshire WA7 6QZ First Proprietor 1 Angel Square Manchester M60 0AG LPA0017 McColls commences 6 Jun 2017 expires 31 Dec 9999 442 Liverpool Road issued 24/11/2005 Widnes reason Variation Cheshire WA8 7XP First Proprietor -

Local Patient Participation Report ( LPPR )

Hough Green Health Park Local Patient Participation Report ( LPPR ) The Practice, Hough Green Health Park (formerly Upton Medical centre), has been on the Upton Estate since 1976 and Dr Kumar moved the practice to purpose made premises in 1985. Dr Koya joined the practice in 2006 as full time GP. After Dr Kumar retired in April 2011, Dr Chalasani has joined the practice as full time partner. The practice later relocated to a purpose designed new premises in September 2011 with name changed to Hough Green Health Park. The new modern and much larger premises provided much needed space which helped to improve the service provision of primary medical services and enhanced the overall patient experience. This also enabled us to provide several additional in-house services to our patients. We consider a personal service to be not only more efficient but also more effective. The staff at Hough Green Health Park is here to work for and look after our patients when they are ill but we also think it is important to give clear guidance and advice on how they can live a long and healthy life. We work closely with Bridgewater NHS Trust staff who are based here and compliment the services provided by the practice team. We are also one of the first `Community Wellbeing practices’ in Widnes which is an initiative commissioned by Halton CCG to improve overall wellbeing of patients and promote health and social care of people living in Halton. Practice facilities Excellent access to the Premises, fully DDA compliant with wheelchair access throughout and