Building a Foundation for Digital Inclusion a Coordinated Local Content Ecosystem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

En Vogue Ana Popovic Artspower National Touring Theatre “The

An Evening with Jazz Trumpeter Art Davis Ana Popovic En Vogue Photo Credit: Ruben Tomas ArtsPower National Alyssa Photo Credit: Thomas Mohr Touring Theatre “The Allgood Rainbow Fish” Photo Courtesy of ArtsPower welcome to North Central College ometimes good things come in small Ana Popovic first came to us as a support act for packages. There is a song “Bigger Isn’t Better” Jonny Lang for our 2015 homecoming concert. S in the Broadway musical “Barnum” sung by When she started on her guitar, Ana had everyone’s the character of Tom Thumb. He tells of his efforts attention. Wow! I am fond of telling people who to prove just because he may be small in stature, he have not been in the concert hall before that it’s a still can have a great influence on the world. That beautiful room that sounds better than it looks. Ana was his career. Now before you think I have finally Popovic is the performer equivalent of my boasts lost it, there is a connection here. February is the about the hall. The universal comment during the smallest month, of the year, of course. Many people break after she performed was that Jonny had better feel that’s a good thing, given the normal prevailing be on his game. Lucky for us, of course, he was. But weather conditions in the month of February in the when I was offered the opportunity to bring Ana Chicagoland area. But this little month (here comes back as the headliner, I jumped at the chance! Fasten the connection!) will have a great influence on the your seatbelts, you are in for an amazing evening! fine arts here at North Central College with the quantity and quality of artists we’re bringing to you. -

Happiness Is

HAPPINESS IS No 2 Vol 13 June 2011 VITAL Page 2 Editorial Inspriational Seminar Page 3 Parenting Night Success in this Issue Internet Safety WelcoMe To the Summer edition of We feature poetry from Gerry Galvin and Seminar happiness is Vital. Find us on facebook and both ‘Medical Matters’ and ‘dear lorraine’ Page 4 Medical Matters follow us on twitter @aidswest for interesting examine issues and concerns affecting readers and inspirational news, videos and and as always we take a look at the latest Page 5 In the News information. medical advancements and news stories Page 6 Dear Lorraine in this issue we revisit AidS West events over relating to hiV from around the world. the past few months including our highly Please check our website for details of Page 7 Poetry with Gerry Galvin successful seminar on ‘coping With upcoming events. i hope you enjoy this issue Adversity’ with inspirational speakers Joan and those long lazy days of Summer in the Page 8 Excerpt from ‘e Freeman, John lonergan and ophelia West of ireland. Keep well, keep safe and Govenor’ haanyama orum. We look back on our above all, for all of us, happiness, each and Page 9 Interview with Ophelia parenting seminar and announce plans for an every day is indeed vital. Parenting seminar tackles tough topics exciting seminar on ‘Parenting and the Tracey Ferguson Page 10 High Times internet’ with full details to be announced e: [email protected] / Find us on Page 11 Useful Services 120 parents get facts and advice on sensitive issues soon. Facebook: www.facebook.com/aidswest AidS WeST held a very successful public seminar on Monday, 21st transmitted infections, the most common being chlamydia where the of March at e Ardilaun hotel. -

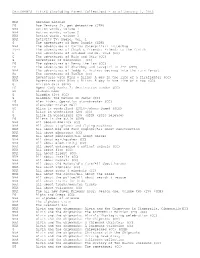

Menlo Park Juvi Dvds Check the Online Catalog for Availability

Menlo Park Juvi DVDs Check the online catalog for availability. List run 09/28/12. J DVD A.LI A. Lincoln and me J DVD ABE Abel's island J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Raggedy Ann & Andy. J DVD ADV The adventures of Curious George J DVD ADV The adventures of Ociee Nash J DVD ADV The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin. J DVD ADV The adventures of Pinocchio J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV The adventures of Tintin J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.1 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.2 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.3 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.4 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.5 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD ADV v.6 The adventures of Swiss family Robinson. J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE Agent Cody Banks J DVD AGE 2 Agent Cody Banks 2 J DVD AIR Air Bud J DVD AIR Air buddies J DVD ALA Aladdin J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALE Alex Rider J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALI Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALICE Alice in Wonderland J DVD ALL All dogs go to heaven J DVD ALL All about fall J DVD ALV Alvin and the chipmunks. -

Big Dreams Sparked by a Spirited Girl Muppet

GLOBAL GIRLS’ EDUCATION Big Dreams Sparked by a Spirited Girl Muppet Globally, an estimated 510 million women grow up unable to read and write – nearly twice the rate of adult illiteracy as men.1 To counter this disparity in countries around the world, there’s Sesame Street. Local adaptations of Sesame Street are opening minds and doors for eager young learners, encouraging girls to dream big and gain the skills they need to succeed in school and life. We know these educational efforts yield benefits far beyond girls’ prospects. They produce a ripple effect that advances entire families and communities. Increased economic productivity, reduced poverty, and lowered infant mortality rates are just a few of the powerful outcomes of educating girls. “ Maybe I’ll be a police officer… maybe a journalist… maybe an astronaut!” Our approach is at work in India, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Egypt, South Africa, Afghanistan, and many other developing countries where educational and professional opportunities for women are limited. — Khokha Afghanistan BAGHCH-E-SIMSIM Bangladesh SISIMPUR Brazil VILA SÉSAMO China BIG BIRD LOOKS AT THE WORLD Colombia PLAZA SÉSAMO Egypt ALAM SIMSIM India GALLI GALLI SIM SIM United States Indonesia JALAN SESAMA Israel RECHOV SUMSUM Mexico PLAZA SÉSAMO Nigeria SESAME SQUARE Northern Ireland SESAME TREE West Bank / Gaza SHARA’A SIMSIM South Africa TAKALANI SESAME Tanzania KILIMANI SESAME GLOBAL GIRLS’ EDUCATION loves about school: having lunch with friends, Watched by millions of children across the Our Approach playing sports, and, of course, learning new country, Baghch-e-Simsim shows real-life girls things every day. in situations that have the power to change Around the world, local versions of Sesame gender attitudes. -

West Islip Public Library

CHILDREN'S TITLES (including Parent Collection) - as of January 1, 2013 NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a firefighter (CC) NRA Adventures with Wink & Blink: A day in the life of a zoo (CC) G African cats (SDH) PG Agent Cody Banks 2: destination London (CC) PG Alabama moon G Aladdin (2v) (CC) G Aladdin: the Return of Jafar (CC) PG Alex Rider: Operation stormbreaker (CC) NRA Alexander Graham Bell PG Alice in wonderland (2010-Johnny Depp) (SDH) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (CC) G Alice in wonderland (2v) (SDH) (2010 release) PG Aliens in the attic (SDH) NRA All aboard America (CC) NRA All about airplanes and flying machines NRA All about big red fire engines/All about construction NRA All about dinosaurs (CC) NRA All about dinosaurs/All about horses NRA All about earthquakes (CC) NRA All about electricity (CC) NRA All about endangered & extinct animals (CC) NRA All about fish (CC) NRA All about -

Proceedings of the World Summit on Television for Children. Final Report.(2Nd, London, England, March 9-13, 1998)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 433 083 PS 027 309 AUTHOR Clarke, Genevieve, Ed. TITLE Proceedings of the World Summit on Television for Children. Final Report.(2nd, London, England, March 9-13, 1998). INSTITUTION Children's Film and Television Foundation, Herts (England). PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 127p. AVAILABLE FROM Children's Film and Television Foundation, Elstree Studios, Borehamwood, Herts WD6 1JG, United Kingdom; Tel: 44(0)181-953-0844; e-mail: [email protected] PUB TYPE Collected Works - Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Children; *Childrens Television; Computer Uses in Education; Foreign Countries; Mass Media Role; *Mass Media Use; *Programming (Broadcast); *Television; *Television Viewing ABSTRACT This report summarizes the presentations and events of the Second World Summit on Television for Children, to which over 180 speakers from 50 countries contributed, with additional delegates speaking in conference sessions and social events. The report includes the following sections:(1) production, including presentations on the child audience, family programs, the preschool audience, children's television role in human rights education, teen programs, and television by kids;(2) politics, including sessions on the v-chip in the United States, the political context for children's television, news, schools television, the use of research, boundaries of children's television, and minority-language television; (3) finance, focusing on children's television as a business;(4) new media, including presentations on computers, interactivity, the Internet, globalization, and multimedia bedrooms; and (5) the future, focusing on anticipation of events by the time of the next World Summit in 2001 and summarizing impressions from the current summit. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright Structured Named Entities Nicky Ringland Supervisor: James Curran A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Information Technologies at The University of Sydney School of Information Technologies 2016 i Abstract The names of people, locations, and organisations play a central role in language, and named entity recognition (NER) has been widely studied, and successfully incorporated, into natural language processing (NLP) applications. -

Choices Child Care Resource and Referral

Categories AT= Assistive Technology IT= Infant and Toddler VAP= Van Active Play VART= Van Art VB= Van Books VB (R)= Van Book Resource VBL= Van Blocks VC= Van Cassette VCD= Van CD VDP=Van Dramatic Play VE= Van Educational VG= Van Game VL= Van Literacy VMTH= Van Math VMUS= Van Music VS= Van Software VSC= Van Science VSEN= Van Sensory VTT= Van Table Toys VV= Van Video AT= Assistive Technology Item # Description Details AT - 1 Voice Pal Max 1 Count AT - 2 Traction Pads Set 0f 5 AT - 3 Free Switch 1 Count AT - 4 Battery Interrupters ½” (AA) AT - 5 Handy Board 1 Count AT - 6 Chipper 1 Count AT - 7 Sequencer 1 Count AT - 8 Magic Arm Knob AT - 9 Mounting Plates for Magic Arm LRMP,LIMP, SRMP,STMP,SCMP AT - 10 Dual Lock (2’ per center) AT- 11 Free Hand Starter Kit 1 Count AT - 12 Overlay Packets 1 Count AT - 13 Battery Interrupters ¾” (C/D) AT - 14 Pal Pads Small, Medium, Large AT - 15 Flexible Switch Large AT - 16 Picture Board 1 Count AT - 17 Sensory Software All Versions AT - 18 Tech Speak 6 x 32 AT - 19 Tech Talk 8 x 8 AT - 20 Stages 1 Count AT - 21 Four Frame Talker 1 Count AT - 22 Qwerty Color Big Keys Plus Keyboard AT - 23 Rag Dolls Set of Eight AT - 24 Adaptive Equipment Complete Set AT - 25 Chirping Easter Egg 1 Count AT - 26 Eye Gaze Board Opticommunicator AT - 27 PCA Checklist 1 Count AT - 28 BIGMack Communication Aid Green AT - 29 Powerlink 3 1 Count AT - 30 Spec Switch Blue AT - 31 Step by Step Communicator w/o Levels Red AT - 32 Easy Ball 6 44.95, 269.70 AT - 33 Old McDonalds Farm Deluxe 1 Count AT - 34 Monkeys Jumping on a Bed 1 -

Nigerian Educators' Appropriation of Sesame Classroom Materials

Global early childhood policies 17 Localizing Play-Based Pedagogy: Nigerian Educators’ Appropriation of Sesame Classroom Materials Naomi A. Moland School of International Service, American University Abstract This article examines how international organizations promote play-based pedagogical approaches in early childhood settings around the world, and how local educators respond. As a case study, I investigated Sesame Workshop’s efforts to introduce play-based approaches in Nigerian classrooms. In addition to producing a Nigerian version of Sesame Street (called Sesame Square), Sesame Workshop trains educators in play-based approaches and has distributed alphabet flashcards, puppet kits, and storytelling games to more than 2,700 early childhood classrooms across Nigeria. These materials were intended to support Sesame Square’s messages, and to foster interactive, child-centered learning experiences. However, teachers often used the materials in ways that reflected more rote-based, teacher- centered approaches. Data was gathered through observations and interviews in 27 educational sites across Nigeria that use Sesame materials. Findings reveal that teachers’ resistance to play-based approaches was sometimes for structural reasons (e.g., large class sizes), and sometimes related to their knowledge and training (e.g., they were accustomed to drilling the alphabet). I argue that ideals about constructivist, play-based learning are being disseminated by international organizations—alongside contrasting formalistic pedagogical approaches—and that all approaches will shift as they are localized. I question if approaches that are considered universally developmentally appropriate are relevant in all settings, and explore how early childhood educators adapt global pedagogical trends to make sense in their classrooms. I call for international organizations to explore context-appropriate play-based approaches that develop educators’ capacities to help all children thrive, while also incorporating local cultural beliefs about childhood and teaching. -

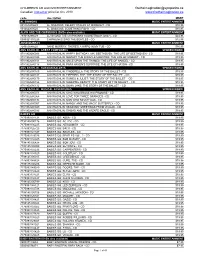

Pompton Lakes DVD Title List

Pompton Lakes DVD Title List Title Call Number MPAA Rating Date Added Release Date 007 A View to A Kill DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 10/2/2012 007 Diamonds are Forever DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 10/2/2012 007 Dr. No BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 For Your Eyes Only BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 9/15/2015 007 From Russia with Love BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2002 007 James Bond: Licence to Kill DVD 007 PG-13 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: On Her Majesty's Secret Service DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Living Daylights DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Pierce Brosnan Collection DVD 007 PG-13 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Roger Moore Collection, vol. 1 DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Roger Moore Collection, vol. 2 DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 James Bond: The Sean Connery Collection, vol. 1 DVD 007 PG 10/6/2015 9/15/2015 007 Live and Let Die BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 Moonraker BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 On Her Majesty's Secret Service DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 5/16/2000 007 The Man with The Golden Gun BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 The Man with the Golden Gun BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 8/17/2012 007 The Spy Who Loved Me DVD 007 PG 8/4/2016 10/2/2012 007 Thunderball BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 12/19/2001 007 You Only Live Twice BLU 007 PG 3/13/2017 9/15/2015 10 Secrets for Success and Inner Peace DVD DYE Not Rated 12/2/2011 3/24/2009 Thursday, June 17, 2021 Page 1 of 231 Title Call Number MPAA Rating Date Added Release Date 10 Things I Hate About You (10th Ann DVD Edition) DVD TEN PG-13 -

Court to Resolve Senate Case Today

nmvAil library ananas QVarietyj Micronesia’s Leading Newspaper Since 1972 Vol. 21 . No. 121 „ ' ■' Saipan, MP 9695Ö ©1992 Marianas Variety Friday ■ September 4,* 1992 Serving CNMI for 20 Years C ourt to resolve Senate case today By Gaynor L. Dumat-ol presiding judge. nity might not apply in this case. “It is our position that the ses He said immunity applies only to THE SUPERIOR Court yester sion is in violation of the court possible slander charges arising day reaffirmed its declaration that order,” Bellas told reporters after from statements made during a Joseph S. Inos was still the the hearing. legislative session or hearing. president of the Senate, despite a Atalig is expected to finally A person found guilty of session called by six senators decide during the continuation of criminal contempt may be im inos Demapan Wednesday afternoon which “re the hearing this afternoon who prisoned for a maximum of six elected” Juan S. Demapan to the between Inos and Demapan is months and/or fined $100. Pierce asked Atalig to declare as merely two-thirds of the mem hotly contested seat legally entitled to occupy the At the Senate yesterday, “moot” Inos’ motion against bership. “The court order still remains,” Senate presidency. Demapan called another session Demapan. .Seven senators originally Presiding Judge Pedro Atalig said If Demapan loses, he and the attended by the same six senators Atalig said he would “solve” signed the memorandum calling during yesterday )s hearing where five other senators who joined who re-elected him Wednesday. today whether the issue raised by fa· Wednesday’s session but Juan only counsels of the two «con the session and voted for him last They passed several resolu Inos has become moot (with the S. -

FTI 2010 CD DVD Consumer Price List

CHILDREN'S CD and DVD ENTERTAINMENT [email protected] Canadian Consumer price list Oct. 2010 www.firetheimagination.ca code description MSRP AL SIMMONS MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 801464200629 AL SIMMONS: CELERY STALKS AT MIDNIGHT - CD $10.95 801464200520 AL SIMMONS: SOMETHING FISHY - CD $10.95 ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS (DVDs also available) MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 793018298629 ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS SOUNDTRACK (2007) - CD $24.95 5099921310225 CHIPMUNKS SING THE BEATLES - CD $12.95 ANNE MURRAY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 724353548520 ANNE MURRAY: THERE'S A HIPPO IN MY TUB - CD $16.95 ANN RACHLIN - GREAT COMPOSERS SPOKEN WORD 9781902680088 ANN RACHLIN: HAPPY BIRTHDAY, MR. BEETHOVEN: THE LIFE OF BEETHOVEN - CD $19.95 9781902680095 ANN RACHLIN: MOZART THE MIRACLE MAESTRO: THE LIFE OF MOZART - CD $19.95 9781902680101 ANN RACHLIN: ONCE UPON THE THAMES: THE LIFE OF HANDEL - CD $19.95 9781902680118 ANN RACHLIN: PAPA HAYDN'S SURPRISE: THE LIFE OF HAYDN - CD $19.95 ANN RACHLIN - RUSSIAN BALLETS SPOKEN WORD 9781902680163 ANN RACHLIN: CINDERELLA: THE STORY OF THE BALLET - CD $19.95 9781902680187 ANN RACHLIN: FIREBIRD, THE: THE STORY OF THE BALLET - CD $19.95 9781902680170 ANN RACHLIN: ROMEO & JULIET: THE STORY OF THE BALLET - CD $19.95 9781902680156 ANN RACHLIN: SLEEPING BEAUTY: THE STORY OF THE BALLET - CD $19.95 9781902680132 ANN RACHLIN: SWAN LAKE: THE STORY OF THE BALLET - CD $19.95 ANN RACHLIN - MUSICAL ADVENTURES SPOKEN WORD 9781902680071 ANN RACHLIN: KING WHO BROKE HIS PROMISE - CD $19.95 9781902680064 ANN RACHLIN: LOVE FOR THREE ORANGES - CD $19.95