5. Science on Expeditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antarctic Peninsula

Hucke-Gaete, R, Torres, D. & Vallejos, V. 1997c. Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, by marine debris at Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Islets, Livingston Island, Antarctica: 1998-1997. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 47: 123-135. Hucke-Gaete, R., Osman, L.P., Moreno, C.A. & Torres, D. 2004. Examining natural population growth from near extinction: the case of the Antarctic fur seal at the South Shetlands, Antarctica. Polar Biology 27 (5): 304–311 Huckstadt, L., Costa, D. P., McDonald, B. I., Tremblay, Y., Crocker, D. E., Goebel, M. E. & Fedak, M. E. 2006. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behavior of Southern Elephant Seals in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006, abstract #OS33A-1684. INACH (Instituto Antártico Chileno) 2010. Chilean Antarctic Program of Scientific Research 2009-2010. Chilean Antarctic Institute Research Projects Department. Santiago, Chile. Kawaguchi, S., Nicol, S., Taki, K. & Naganobu, M. 2006. Fishing ground selection in the Antarctic krill fishery: Trends in patterns across years, seasons and nations. CCAMLR Science, 13: 117–141. Krause, D. J., Goebel, M. E., Marshall, G. J., & Abernathy, K. (2015). Novel foraging strategies observed in a growing leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) population at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Animal Biotelemetry, 3:24. Krause, D.J., Goebel, M.E., Marshall. G.J. & Abernathy, K. In Press. Summer diving and haul-out behavior of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) near mesopredator breeding colonies at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Mammal Science.Leppe, M., Fernandoy, F., Palma-Heldt, S. & Moisan, P 2004. Flora mesozoica en los depósitos morrénicos de cabo Shirreff, isla Livingston, Shetland del Sur, Península Antártica, in Actas del 10º Congreso Geológico Chileno. -

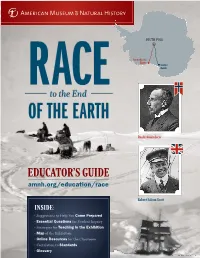

Educator's Guide

SOUTH POLE Amundsen’s Route Scott’s Route Roald Amundsen EDUCATOR’S GUIDE amnh.org/education/race Robert Falcon Scott INSIDE: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Essential Questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Map of the Exhibition • Online Resources for the Classroom • Correlation to Standards • Glossary ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS Who would be fi rst to set foot at the South Pole, Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen or British Naval offi cer Robert Falcon Scott? Tracing their heroic journeys, this exhibition portrays the harsh environment and scientifi c importance of the last continent to be explored. Use the Essential Questions below to connect the exhibition’s themes to your curriculum. What do explorers need to survive during What is Antarctica? Antarctica is Earth’s southernmost continent. About the size of the polar expeditions? United States and Mexico combined, it’s almost entirely covered Exploring Antarc- by a thick ice sheet that gives it the highest average elevation of tica involved great any continent. This ice sheet contains 90% of the world’s land ice, danger and un- which represents 70% of its fresh water. Antarctica is the coldest imaginable physical place on Earth, and an encircling polar ocean current keeps it hardship. Hazards that way. Winds blowing out of the continent’s core can reach included snow over 320 kilometers per hour (200 mph), making it the windiest. blindness, malnu- Since most of Antarctica receives no precipitation at all, it’s also trition, frostbite, the driest place on Earth. Its landforms include high plateaus and crevasses, and active volcanoes. -

The Diaries of Tryggve Gran

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 12 NOVEMBER 2 0 1 8 THE DIAR IES OF TRYGGVE GRAN A SUPREMELY IMPORTANT PIECE OF POLAR HISTORY INCLUDING A FIRST-HAND ACCOUNT OF THE TRAGIC DISCOVERY OF SCOTT’S TENT December – On 12 December, as part of Classic Week, Christie’s auction of Books and Manuscripts will offer two extraordinary sledging journals of the Norwegian polar explorer Tryggve Gran, who accompanied Robert Falcon Scott on the Terra Nova Expedition of 1910 - 1913. The journals have passed by direct descent from Tryggve Gran; their appearance at auction represents a remarkable opportunity to acquire an authentic piece of Polar history, offering an insight into the trials and tribulations of the British Antarctic Expedition here. Featuring two separate journals, one in English and one in Norwegian (estimate: £120,000 - £180,000, illustrated above), these accounts offer additional material, covering his astonishingly prescient dream on the night of 14 December 1911 of Amundsen’s triumph, as well as the search for Scott’s polar party and tragic discovery of the tent. The young Norwegian Tryggve Gran was recruited by Scott as a skiing expert for the Terra Nova Expedition on the recommendation of the explorer and humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen. He would go on to play a valuable role in the second geological expedition (November 1911-February 1912), which collected data in the Granite Harbour region. A particularly emotional entry in his diary takes place on 12 November 1912, when Gran discovered the tent with the frozen bodies of Scott, Wilson and Bowers: ‘It has happened – we have found what we sought – horrible, ugly fate – Only 11 miles from One Ton Depot – The Owner, Wilson & Birdie. -

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS from POLAR and SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W

BOLD ENDEAVORS: BEHAVIORAL LESSONS FROM POLAR AND SPACE EXPLORATION Jack W. Stuster Anacapa Sciences, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA ABSTRACT Material in this article was drawn from several chapters of the author’s book, Bold Endeavors: Lessons from Polar and Space Anecdotal comparisons frequently are made between Exploration. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. 1996). expeditions of the past and space missions of the future. the crew gradually became afflicted with a strange and persistent Spacecraft are far more complex than sailing ships, but melancholy. As the weeks blended one into another, the from a psychological perspective, the differences are few condition deepened into depression and then despair. between confinement in a small wooden ship locked in the Eventually, crew members lost almost all motivation and found polar ice cap and confinement in a small high-technology it difficult to concentrate or even to eat. One man weakened and ship hurtling through interplanetary space. This paper died of a heart ailment that Cook believed was caused, at least in discusses some of the behavioral lessons that can be part, by his terror of the darkness. Another crewman became learned from previous expeditions and applied to facilitate obsessed with the notion that others intended to kill him; when human adjustment and performance during future space he slept, he squeezed himself into a small recess in the ship so expeditions of long duration. that he could not easily be found. Yet another man succumbed to hysteria that rendered him temporarily deaf and unable to speak. Additional members of the crew were disturbed in other ways. -

Scott's Discovery Expedition

New Light on the British National Antarctic Expedition (Scott’s Discovery Expedition) 1901-1904. Andrew Atkin Graduate Certificate in Antarctic Studies (GCAS X), 2007/2008 CONTENTS 1 Preamble 1.1 The Canterbury connection……………...………………….…………4 1.2 Primary sources of note………………………………………..………4 1.3 Intent of this paper…………………………………………………...…5 2 Bernacchi’s road to Discovery 2.1 Maria Island to Melbourne………………………………….…….……6 2.2 “.…that unmitigated fraud ‘Borky’ ……………………….……..….….7 2.3 Legacies of the Southern Cross…………………………….…….…..8 2.4 Fellowship and Authorship………………………………...…..………9 2.5 Appointment to NAE………………………………………….……….10 2.6 From Potsdam to Christchurch…………………………….………...11 2.7 Return to Cape Adare……………………………………….….…….12 2.8 Arrival in Winter Quarters-establishing magnetic observatory…...13 2.9 The importance of status………………………….……………….…14 3 Deeds of “Derring Doe” 3.1 Objectives-conflicting agendas…………………….……………..….15 3.2 Chivalrous deeds…………………………………….……………..…16 3.3 Scientists as Heroes……………………………….…….……………19 3.4 Confused roles……………………………….……..………….…...…21 3.5 Fame or obscurity? ……………………………………..…...….……22 2 4 “Scarcely and Exhibition of Control” 4.1 Experiments……………………………………………………………27 4.2 “The Only Intelligent Transport” …………………………………….28 4.3 “… a blasphemous frame of mind”……………………………….…32 4.4 “… far from a picnic” …………………………………………………34 4.5 “Usual retine Work diggin out Boats”………...………………..……37 4.6 Equipment…………………………………………………….……….38 4.8 Reflections on management…………………………………….…..39 5 “Walking to Christchurch” 5.1 Naval routines………………………………………………………….43 -

Robert F. Scott and the Terra Nova Expedition 1910 – 1913

Robert F. Scott and the Terra Nova Expedition 1910 – 1913 The Fram Museum, June 7 2012 The Fram Museum celebrates the opening of a new exhibition on Robert F. Scott and the Terra Nova Expedition 1910 – 1913 with a seminar and a seated dinner on the deck of the Fram. The exhibition tells the amazing story of the Terra Nova Expedition and contains a large number of the striking photos and original artifacts from the expedition. The artifacts includes expedition and personal equipment, watercolours by Edward A. Wilson, pieces of Amundsen’s tent that was left at the South Pole, and the Norwegian depot flag found by Scott and his team before they arrived at the Pole. The exhibition is made in cooperation with Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge. SPRI has also generously lent us the artifacts for the exhibit. We are honoured to welcome prominent experts on the Terra Nova Expedition for the seminar. The speakers will join us for dinner and their books are available in the museum store. The dinner is a four course meal prepared by the Fram’s chef Tommy Østhagen and Kreativ Catering. Program: 14:00 Welcome and opening remarks Geir O. Kløver, Director of the Fram Museum 14:15 Science and the Pole on Scott’s Terra Nova Expedition Beau Riffenburgh 15:15 ‘Six brave men’ - Scott’s Northern Party Meredith Hooper 16:00 Coffee break 16:30 Bringing Dead Men To Life – How Scott and Amundsen inspire modern literature Richard Pierce 17:15 Antarctica 2012 - a personal experience by Capt. Scott’s grandson Falcon Scott 18:15 Closing remarks 18:30 Opening of the exhibition Robert F. -

The Centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’S Enduring Scientific Legacy and Ongoing Presence There”

Debate on 18 October: Scott Expedition to Antarctica and Scientific Legacy This Library Note provides background reading for the debate to be held on Thursday, 18 October: “the centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’s enduring scientific legacy and ongoing presence there” The Note provides information on Antarctica’s geography and environment; provides a history of its exploration; outlines the international agreements that govern the territory; and summarises international scientific cooperation and the UK’s continuing role and presence. Ian Cruse 15 October 2012 LLN 2012/034 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of the House of Lords and their personal staff, to provide impartial, politically balanced briefing on subjects likely to be of interest to Members of the Lords. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1.1 Geophysics of Antarctica ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Environmental Concerns about the Antarctic ......................................................... 2 2.1 Britain’s Early Interest in the Antarctic .................................................................... 4 2.2 Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration ....................................................................... -

INAUGURAL SEASON 2020-2021 Antarctica | Greenland & Iceland

EXPEDITION CRUISES INAUGURAL SEASON 2020-2021 Antarctica | Svalbard | Greenland & Iceland | Norway & Russia | Northwest Passage | North, Central & South America | Europe new Alaska & Canada Content 2020-21 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– We take you far beyond the ordinary 6-7 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Our Expedition Fleet 8-9 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– The future is green 10-11 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Antarctica 12-15 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Greenland & Iceland 16-19 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Russia 19 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Svalbard 20-23 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Norway 24-25 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Northwest Passage 26-27 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Alaska & Canada 28-29 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– North & Central America 30 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– South America 31 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Europe 32 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Extend your stay 32-33 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Terms and conditions 34-37 ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– 2 “Ever since Hurtigruten started sailing polar waters back in 1893, we have been on a constant look out for new worlds to explore.” © HURTIGRUTEN Hurtigruten is an exploration company in the truest sense of the word; our mission is to bring adventurers to remote natural beauty around the world. Our experience in the feld is unparalleled, and we draw on our unique -

Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2014 Herbert Ponting; Picturing the Great White South Maggie Downing CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/328 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The City College of New York Herbert Ponting: Picturing the Great White South Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York. by Maggie Downing New York, New York May 2014 Dedicated to my Mother Acknowledgments I wish to thank, first and foremost my advisor and mentor, Prof. Ellen Handy. This thesis would never have been possible without her continuing support and guidance throughout my career at City College, and her patience and dedication during the writing process. I would also like to thank the rest of my thesis committee, Prof. Lise Kjaer and Prof. Craig Houser for their ongoing support and advice. This thesis was made possible with the assistance of everyone who was a part of the Connor Study Abroad Fellowship committee, which allowed me to travel abroad to the Scott Polar Research Institute in Cambridge, UK. Special thanks goes to Moe Liu- D'Albero, Director of Budget and Operations for the Division of the Humanities and the Arts, who worked the bureaucratic college award system to get the funds to me in time. -

Scurvy? Is a Certain There Amount of Medical Sure, for Know That Sheds Light on These Questions

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2013; 43:175–81 Paper http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2013.217 © 2013 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh The role of scurvy in Scott’s return from the South Pole AR Butler Honorary Professor of Medical Science, Medical School, University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK ABSTRACT Scurvy, caused by lack of vitamin C, was a major problem for polar Correspondence to AR Butler, explorers. It may have contributed to the general ill-health of the members of Purdie Building, University of St Andrews, Scott’s polar party in 1912 but their deaths are more likely to have been caused by St Andrews KY16 9ST, a combination of frostbite, malnutrition and hypothermia. Some have argued that Scotland, UK Oates’s war wound in particular suffered dehiscence caused by a lack of vitamin C, but there is little evidence to support this. At the time, many doctors in Britain tel. +44 (0)1334 474720 overlooked the results of the experiments by Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich e-mail [email protected] which showed the effects of nutritional deficiencies and continued to accept the view, championed by Sir Almroth Wright, that polar scurvy was due to ptomaine poisoning from tainted pemmican. Because of this, any advice given to Scott during his preparations would probably not have helped him minimise the effect of scurvy on the members of his party. KEYWORDS Polar exploration, scurvy, Robert Falcon Scott, Lawrence Oates DECLaratIONS OF INTERESTS No conflicts of interest declared. INTRODUCTION The year 2012 marked the centenary of Robert -

The Reception and Commemoration of William Speirs Bruce Are, I Suggest, Part

The University of Edinburgh School of Geosciences Institute of Geography A SCOT OF THE ANTARCTIC: THE RECEPTION AND COMMEMORATION OF WILLIAM SPEIRS BRUCE M.Sc. by Research in Geography Innes M. Keighren 12 September 2003 Declaration of originality I hereby declare that this dissertation has been composed by me and is based on my own work. 12 September 2003 ii Abstract 2002–2004 marks the centenary of the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition. Led by the Scots naturalist and oceanographer William Speirs Bruce (1867–1921), the Expedition, a two-year exploration of the Weddell Sea, was an exercise in scientific accumulation, rather than territorial acquisition. Distinct in its focus from that of other expeditions undertaken during the ‘Heroic Age’ of polar exploration, the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, and Bruce in particular, were subject to a distinct press interpretation. From an examination of contemporary newspaper reports, this thesis traces the popular reception of Bruce—revealing how geographies of reporting and of reading engendered locally particular understandings of him. Inspired, too, by recent work in the history of science outlining the constitutive significance of place, this study considers the influence of certain important spaces—venues of collection, analysis, and display—on the conception, communication, and reception of Bruce’s polar knowledge. Finally, from the perspective afforded by the centenary of his Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, this paper illustrates how space and place have conspired, also, to direct Bruce’s ‘commemorative trajectory’—to define the ways in which, and by whom, Bruce has been remembered since his death. iii Acknowledgements For their advice, assistance, and encouragement during the research and writing of this thesis I should like to thank Michael Bolik (University of Dundee); Margaret Deacon (Southampton Oceanography Centre); Graham Durant (Hunterian Museum); Narve Fulsås (University of Tromsø); Stanley K. -

A Century Ago : the Nansen Drift Fridtjof Nansen Wanted to Reach the Pole by Having His Boat Caught in the Ice and Letting Her Drift

www.taraexpeditions.org A century ago : the Nansen drift Fridtjof Nansen wanted to reach the pole by having his boat caught in the ice and letting her drift. He will miss his objective by some 800 km but will bring back all his crew despite three very harsh wintering. In 1895, a Norwegian succeeded in com- pleting the fi rst Arctic drift on the Fram, the boat that is Tara’s ancestor. Prolonged for three long polar winters, the mission, however, was not able to reach the pole. Fridtjof Nansen was 32 years old when he Her rounded shapes should prevent the ice from March 1895, Nansen decides to leave the boat had begun on the journey. During the summer, started on his Arctic drift. His aim was to get crushing her, but it is especially her sturdiness and go with a companion to the North Pole the pack ice becomes more and more impracti- as close to the North pole as possible. It is after that enables her to resist to the pack ice grip : the by sledge. Th e two men are equipped with cable but at the end of August, they accost on having discovered in the south west of Green- hull is more than 80 centimetres thick. light kayaks and take 630 kg of equipment with land on the Franz-Joseph archipelago. Th ey re- land the remains of a vessel crushed by the ice, With a crew of 13 men, Nansen leaves Oslo them. After 23 days on the go, they give up on solve to spend their third Arctic winter.