Essays on Benjamin Britten from a Centenary Symposium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Britten Spring Symphony Welcome Ode • Psalm 150

BRITTEN SPRING SYMPHONY WELCOME ODE • PSALM 150 Elizabeth Gale soprano London Symphony Chorus Alfreda Hodgson contralto Martyn Hill tenor London Symphony Orchestra Southend Boys’ Choir Richard Hickox Greg Barrett Richard Hickox (1948 – 2008) Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) Spring Symphony, Op. 44* 44:44 For Soprano, Alto and Tenor solos, Mixed Chorus, Boys’ Choir and Orchestra Part I 1 Introduction. Lento, senza rigore 10:03 2 The Merry Cuckoo. Vivace 1:57 3 Spring, the Sweet Spring. Allegro con slancio 1:47 4 The Driving Boy. Allegro molto 1:58 5 The Morning Star. Molto moderato ma giocoso 3:07 Part II 6 Welcome Maids of Honour. Allegretto rubato 2:38 7 Waters Above. Molto moderato e tranquillo 2:23 8 Out on the Lawn I lie in Bed. Adagio molto tranquillo 6:37 Part III 9 When will my May come. Allegro impetuoso 2:25 10 Fair and Fair. Allegretto grazioso 2:13 11 Sound the Flute. Allegretto molto mosso 1:24 Part IV 12 Finale. Moderato alla valse – Allegro pesante 7:56 3 Welcome Ode, Op. 95† 8:16 13 1 March. Broad and rhythmic (Maestoso) 1:52 14 2 Jig. Quick 1:20 15 3 Roundel. Slower 2:38 16 4 Modulation 0:39 17 5 Canon. Moving on 1:46 18 Psalm 150, Op. 67‡ 5:31 Kurt-Hans Goedicke, LSO timpani Lively March – Lightly – Very lively TT 58:48 4 Elizabeth Gale soprano* Alfreda Hodgson contralto* Martyn Hill tenor* The Southend Boys’ Choir* Michael Crabb director Senior Choirs of the City of London School for Girls† Maggie Donnelly director Senior Choirs of the City of London School† Anthony Gould director Junior Choirs of the City of London School -

LOUISE ALDER | JOSEPH MIDDLETON Serge Rachmaninoff, Ativanovka, Hisfamily’S Country Estate,C

RACHMANINOFF TCHAIKOVSKY BRITTEN GRIEG SIBELIUS MEDTNER LOUISE ALDER | JOSEPH MIDDLETON Serge Rachmaninoff, at Ivanovka, his family’s country estate, c. 1915 estate,c. country hisfamily’s atIvanovka, Serge Rachmaninoff, AKG Images, London / Album / Fine Art Images Lines Written during a Sleepless Night – The Russian Connection Serge Rachmaninoff (1873 – 1943) Six Songs, Op. 38 (1916) 15:28 1 1 At night in my garden (Ночью в саду у меня). Lento 1:52 2 2 To Her (К ней). Andante – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Tempo precedente – Tempo I (Meno mosso) – Meno mosso 2:47 3 3 Daisies (Маргаритки). Lento – Poco più mosso 2:29 4 4 The Rat Catcher (Крысолов). Non allegro. Scherzando – Poco meno mosso – Tempo come prima – Più mosso – Tempo I 2:42 5 5 Dream (Сон). Lento – Meno mosso 3:23 6 6 A-oo (Ау). Andante – Tempo più vivo. Appassionato – Tempo precedente – Più vivo – Meno mosso 2:15 3 Jean Sibelius (1865 – 1957) 7 Våren flyktar hastigt, Op. 13 No. 4 (1891) 1:35 (Spring flees hastily) from Sju sånger (Seven Songs) Vivace – Vivace – Più lento – Vivace – Più lento – Vivace 8 Säv, säv, susa, Op. 36 No. 4 (1900?) 2:32 (Reed, reed, whistle) from Sex sånger (Six Songs) Andantino – Poco con moto – Poco largamente – Molto tranquillo 9 Flickan kom ifrån sin älsklings möte, Op. 37 No. 5 (1901) 2:59 (The girl came from meeting her lover) from Fem sånger (Five Songs) Moderato 10 Var det en dröm?, Op. 37 No. 4 (1902) 2:04 (Was it a dream?) from Fem sånger (Five Songs) Till Fru Ida Ekman Moderato 4 Edvard Grieg (1843 – 1907) Seks Sange, Op. -

Mass in G Minor

MASS IN G MINOR VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: string of works broadly appropriate to worship MASS IN G MINOR appeared in quick succession (more than half Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958) of the music recorded here emerged during this Vaughan Williams wrote of music as a means of period). Some pieces were commissioned for Mass in G Minor ‘stretching out to the ultimate realities through specific events, or were inspired by particular 1 Kyrie [4.42] the medium of beauty’, enabling an experience performers. But the role of the War in prompting the intensified devotional fervour 2 Gloria in excelsis [4.18] of transcendence both for creator and receiver. Yet – even at its most personal and remote, apparent in many of the works he composed 3 Credo [6.53] as often on this disc – his church music also in its wake should not be overlooked. As a 4 Sanctus – Osanna I – Benedictus – Osanna II [5.21] stands as a public testament to his belief wagon orderly, one of Vaughan Williams’s more 5 Agnus Dei [4.41] in the role of art within the earthly harrowing duties was the recovery of bodies realm of a community’s everyday life. He wounded in battle. Ursula Vaughan Williams, 6 Te Deum in G [7.44] embraced the church as a place in which a his second wife and biographer, wrote that 7 O vos omnes [5.59] broad populace might regularly encounter a such work ‘gave Ralph vivid awareness of 8 Antiphon (from Five Mystical Songs) [3.15] shared cultural heritage, participating actively, how men died’. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

16-12 Prog.Pdf

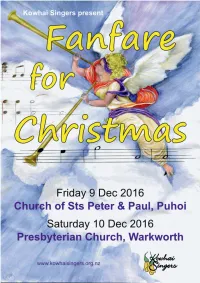

Fanfare for Christmas The title of our concert is taken from our opening song for the full choir - Fanfare for Christmas Day: Gloria in Excelsis Deo, an anthem, by Martin Shaw. Martin Edward Fallas Shaw OBE FRCM (1875 – 1958) was an English composer, conductor and (in his early life) theatre producer. His over 300 published works include songs, hymns, carols, oratorios, several instrumental works, a congregational mass setting (the Anglican Folk Mass) and four operas including a ballad opera With a voice of Singing is another of his anthems in our repertoire, performed several times in the past at Kowhai Singers concerts. Conductor Peter Cammell (BA, Post Grad. Dip. Mus.) studied music at Auckland and Otago Universities and then taught in secondary schools in both Auckland and London. He has sung in the Dorian Choir, Auckland Anglican Cathedral Choir, Cantus Firmus, The Graduate Choir, Musica Sacra, Viva Voce, and is currently with Calico Jam. As director of the Kowhai Singers for 21 years Peter has worked hard to extend the choir's repertoire and singing skills and thereby their musical understanding. Accompanist Riette Ferreira (PhD) has been the choir's pianist for most of the time since August 2003 except when personal commitments such as study towards her PhD degree in Music has taken her away from us. She has wide experience teaching music in both South African and New Zealand schools and is frequently engaged as director and/or keyboard player for musical theatre productions at Centrestage Theatre, Orewa. Introit - Beata Viscera Marie Virginis† (words 12th C) Pontin Fanfare for Christmas Day: Gloria in Excelsis Deo Martin Shaw While shepherds watched their flocks (with the congregation) Welcome, Yule! (Anon. -

Walton - a List of Works & Discography

SIR WILLIAM WALTON - A LIST OF WORKS & DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Martin Rutherford, Penang 2009 See end for sources and legend. Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Catalogue No F'mat St Rel A BIRTHDAY FANFARE Description For Seven Trumpets and Percussion Completion 1981, Ischia Dedication For Karl-Friedrich Still, a neighbour on Ischia, on his 70th birthday First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Recklinghausen First 10-Oct-81 Westphalia SO Karl Rickenbacher Royal Albert Hall L'don 7-Jun-82 Kneller Hall G E Evans A LITANY - ORIGINAL VERSION Description For Unaccompanied Mixed Voices Completion Easter, 1916 Oxford First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.03 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - FIRST REVISION Description First revision by the Composer Completion 1917 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel Hereford Cathedral 3.14 4-Jan-02 Stephen Layton Polyphony 01a HYP CDA 67330 CD S Jun-02 A LITANY - SECOND REVISION Description Second revision by the Composer Completion 1930 First Performances Type Date Orchestra Conductor Performers Unknown Recording Venue Time Date Orchestra Conductor Performers No. Coy Co Cat No F'mat St Rel St Johns, Cambridge ? Jan-62 George Guest St Johns, Cambridge 01a ARG ZRG -

The Development of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Music Department Honors Papers Music Department 1-1-2011 The evelopmeD nt of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams Currie Huntington Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/musichp Recommended Citation Huntington, Currie, "The eD velopment of English Choral Style in Two Early Works of Ralph Vaughan Williams" (2011). Music Department Honors Papers. Paper 2. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/musichp/2 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Music Department at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Music Department Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. THE DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH CHORAL STYLE IN TWO EARLY WORKS OF RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS An Honors Thesis presented by Currie Huntington to the Department of Music at Connecticut College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field and for the Concentration in Historical Musicology Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May 5th, 2011 ABSTRACT The late 19th century was a time when England was seen from the outside as musically unoriginal. The music community was active, certainly, but no English composer since Handel had reached the level of esteem granted the leading continental composers. Leading up to the turn of the 20th century, though, the early stages of a musical renaissance could be seen, with the rise to prominence of Charles Stanford and Hubert Parry, followed by Elgar and Delius. -

BENJAMIN BRITTEN a Ceremony of Carols IRELAND | BRIDGE | HOLST

BENJAMIN BRITTEN A Ceremony of Carols IRELAND | BRIDGE | HOLST Choir of Clare College, Cambridge Graham Ross FRANZ LISZT A Ceremony of Carols BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913-1976) ANONYMOUS, arr. BENJAMIN BRITTEN 1 | Venite exultemus Domino 4’11 12 | The Holly and the Ivy 3’36 for mixed choir and organ (1961) traditional folksong, arranged for mixed choir a cappella (1957) 2 | Te Deum in C 7’40 for mixed choir and organ (1934) BENJAMIN BRITTEN 3 | Jubilate Deo in C 2’30 13 | Sweet was the song the Virgin sung 2’45 for mixed choir and organ (1961) from Christ’s Nativity for soprano and mixed choir a cappella (1931) 4 | Deus in adjutorium meum intende 4’37 from This Way to the Tomb for mixed choir a cappella (1944-45) A Ceremony of Carols op. 28 (1942, rev. 1943) version for mixed choir and harp arranged by JULIUS HARRISON (1885-1963) 5 | A Hymn to the Virgin 3’23 for solo SATB and mixed choir a cappella (1930, rev. 1934) 14 | 1. Procession 1’18 6 | A Hymn of St Columba 2’01 15 | 2. Wolcum Yole! 1’21 for mixed choir and organ (1962) 16 | 3. There is no rose 2’27 7 | Hymn to St Peter op. 56a 5’57 17 | 4a. That yongë child 1’50 for mixed choir and organ (1955) 18 | 4b. Balulalow 1’18 19 | 5. As dew in Aprille 0’56 JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) 20 | 6. This little babe 1’24 8 | The Holy Boy 2’50 version for mixed choir a cappella (1941) 21 | 7. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1946

TANGLEWOOD— LENOX, MASSACHUSETTS THE Berkshire Music Center SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Director presents " ! cc PETER GRIMES" 11 by BENJAMIN BRITTEN Tuesday Evening, August 6 Wednesday Evening, August 7 Friday Evening, August 9 IP •*• 1946 W' !.«.w,a'i STEINWiV Since the time of Liszt, the Steinway has consistently been, year after year, the medium chosen by an overwhelming number of concert artists to express their art. Eugene List, Mischa El man and William Kroll, soloists of this Berk- shire Festival, use the Steinway. Significantly enough, the younger artists, the Masters of tomorrow, entrust their future to this world-famous piano — they cannot afford otherwise to en- danger their artistic careers. The Stein- way is, and ever has been, the Glory Road of the Immortals. M. STEINERT & SONS CO. : 162 BOYLSTON ST., BOSTON Jerome F. Murphy, President • Also Worcester and Springfield THEATRE-CONCERT HALL TANGLEWOOD (Between Stockbridge and Lenox, Massachusetts) Berkshire Music Center . SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Director Season 1946 Program Bulletin with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1946, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, InC. The trustees of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Henry B. Sawyer Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Philip R. Allen M. A. De Wolfe Howe John Nicholas Brown Jacob J. Kaplan Alvan T. Fuller Roger I. Lee Jerome D. Greene Bentley W. Warren N, Penrose Hallowell Raymond S. Wilkins Francis W. Hatch Oliver Wolcott TANGLEWOOD ADVISORY COMMITTEE Allan J. Blau G. Churchill Francis George P. Clayson Lawrence K. Miller Bruce Crane James T. Owens Henry W. Dwight Lester Roberts George W. Edman Whitney S. -

Newsletter 32

The W. H. Auden Society Newsletter Number 32 ● July 2009 Memberships and Subscriptions Annual memberships include a subscription to the Newsletter: Contents Individual members £9 $15 Katherine Bucknell: Edward Upward (1903-2009) 5 Students £5 $8 Nicholas Jenkins: Institutions and paper copies £18 $30 Lost and Found . and Offered for Sale 14 Hugh Wright: W. H. Auden and the Grasshopper of 1955 16 New members of the Society and members wishing to renew should David Collard: either ( a) pay online with any currency by following the link at A New DVD in the G.P.O. Film Collection 18 http://audensociety.org/membership.html Recent and Forthcoming Books and Events 24 or ( b) use postal mail to send sterling (not dollar!) cheques payable to “The W. H. Auden Society” to Katherine Bucknell, Memberships and Subscriptions 26 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW, Receipts available on request. A Note to Members The W. H. Auden Society is registered with the Charity Commission for England and Wales as Charity No. 1104496. The Society’s membership fees no longer cover the costs of printing and mailing the Newsletter . The Newsletter will continue to appear, but The Newsletter is edited by Farnoosh Fathi. Submissions this number will be the last to be distributed on paper to all members. may be made by post to: The W. H. Auden Society, Future issues of the Newsletter will be posted in electronic form on the 78 Clarendon Road, London W11 2HW; or by Society’s web site, and a password that gives access to the Newsletter e-mail to: [email protected] will be made available to members. -

Wexford Carol 1

q = 64 Wexford Carol 1. Good peo - ple all, this Christ-mas- time, con - si - der well and 2. The night be - fore that hap - py tide, the no - ble Vir - gin 3. Near Beth- le - hem did shep-herds keep theirflocks of lambs and 4. With thank-ful heart and joy - ful mind, the shep-herds went the 5. There were three wise men from a - far di - rec - ted by a bear in mind what our good God for us has done, in and her guide were long time seek - ing up and down to feed -ing sheep; to whom God's an - gels did ap - pear, which babe to find, and as God's an - gel had fore - told, they glo-rious star, and on they wan - dered night and day un- send-ing his be -lo - ved son. With Ma - ry ho - ly find a lodg - ing in the town. But mark how all things put the shep - herds in great fear. "Pre - pare and go," the did our Sav - ior Christ be - hold. With - in a man - ger til they came where Je - sus lay. And when they came un - WORDS: Traditional English and Irish (Mt. 1:18-2:11; Luke 2:1-20) WEXFORD CAROL MUSIC: Traditional Irish melody, arr. Martin Shaw (1875-1958) LMD Published by The General Board of Discipleship of The United Methodist Church, PO Box 340003, Nashville TN 37203. Website www.gbod.org/worship Source: The Oxford Book of Carols, compiled and edited by Percy Dearmer, R. Vaughan Williams, Martin Shaw. -

Billy Budd Composer Biography: Benjamin Britten

Billy Budd Composer Biography: Benjamin Britten Britten was born, by happy coincidence, on St. Cecilia's Day, at the family home in Lowestoft, Suffolk, England. His father was a dentist. He was the youngest of four children, with a brother, Robert (1907), and two sisters, Barbara (1902) and Beth (1909). He was educated locally, and studied, first, piano, and then, later, viola, from private teachers. He began to compose as early as 1919, and after about 1922, composed steadily until his death. At a concert in 1927, conducted by composer Frank Bridge, he met Bridge, later showed him several of his compositions, and ultimately Bridge took him on as a private pupil. After two years at Gresham's School in Holt, Norfolk, he entered the Royal College of Music in London (1930) where he studied composition with John Ireland and piano with Arthur Benjamin. During his stay at the RCM he won several prizes for his compositions. He completed a choral work, A Boy was Born, in 1933; at a rehearsal for a broadcast performance of the work by the BBC Singers, he met tenor Peter Pears, the beginning of a lifelong personal and professional relationship. (Many of Britten's solo songs, choral and operatic works feature the tenor voice, and Pears was the designated soloist at many of their premieres.) From about 1935 until the beginning of World War II, Britten did a great deal of composing for the GPO Film Unit, for BBC Radio, and for small, usually left-wing, theater groups in London. During this period he met and worked frequently with the poet W.