Boys' Voices, Lads' Voices: Benjamin Britten and the “Raggazo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Britten Spring Symphony Welcome Ode • Psalm 150

BRITTEN SPRING SYMPHONY WELCOME ODE • PSALM 150 Elizabeth Gale soprano London Symphony Chorus Alfreda Hodgson contralto Martyn Hill tenor London Symphony Orchestra Southend Boys’ Choir Richard Hickox Greg Barrett Richard Hickox (1948 – 2008) Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) Spring Symphony, Op. 44* 44:44 For Soprano, Alto and Tenor solos, Mixed Chorus, Boys’ Choir and Orchestra Part I 1 Introduction. Lento, senza rigore 10:03 2 The Merry Cuckoo. Vivace 1:57 3 Spring, the Sweet Spring. Allegro con slancio 1:47 4 The Driving Boy. Allegro molto 1:58 5 The Morning Star. Molto moderato ma giocoso 3:07 Part II 6 Welcome Maids of Honour. Allegretto rubato 2:38 7 Waters Above. Molto moderato e tranquillo 2:23 8 Out on the Lawn I lie in Bed. Adagio molto tranquillo 6:37 Part III 9 When will my May come. Allegro impetuoso 2:25 10 Fair and Fair. Allegretto grazioso 2:13 11 Sound the Flute. Allegretto molto mosso 1:24 Part IV 12 Finale. Moderato alla valse – Allegro pesante 7:56 3 Welcome Ode, Op. 95† 8:16 13 1 March. Broad and rhythmic (Maestoso) 1:52 14 2 Jig. Quick 1:20 15 3 Roundel. Slower 2:38 16 4 Modulation 0:39 17 5 Canon. Moving on 1:46 18 Psalm 150, Op. 67‡ 5:31 Kurt-Hans Goedicke, LSO timpani Lively March – Lightly – Very lively TT 58:48 4 Elizabeth Gale soprano* Alfreda Hodgson contralto* Martyn Hill tenor* The Southend Boys’ Choir* Michael Crabb director Senior Choirs of the City of London School for Girls† Maggie Donnelly director Senior Choirs of the City of London School† Anthony Gould director Junior Choirs of the City of London School -

Owen Wingrave

OWEN WINGRAVE Oper in zwei Akten von Benjamin Britten Libretto von Myfanwy Piper nach der gleichnamigen Kurzgeschichte von Henry James Eine Veranstaltung des Departements für Oper und Musiktheater in Kooperation mit dem Departement für Bühnen- und Kostümgestaltung, Film- und Ausstellungsarchitektur Montag, 20. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr Dienstag, 21. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr Mittwoch, 22. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr (Livestream) Donnerstag, 23. Jänner 2020 | 19.00 Uhr Max Schlereth Saal Universität Mozarteum Mirabellplatz 1 BESETZUNG Owen Wingrave Taesung Kim (20.1./22.1.)/Benjamin Sattlecker (21.1./23.1.) Musikalische Einstudierung Julia Antonovitch, Dariusz Burnecki, Stefan Müller, Walewein Witten Spencer Coyle Xiaofei Liu (20.1./22.1.)/Qi Wang (21.1./23.1.) Szenische Assistenz Agnieszka Lis Lechmere Johannes Hubmer Schauspielcoaching Natalie Forester Miss Wingrave Julia Heiler Sprachcoaching Theresa McDougall Mrs. Coyle Veronika Loy (20.1./22.1.)/Sophie Negoïta (21.1./23.1.) Szenischer Kampf Ulf Kirschhofer Mrs. Julian Chelsea Kolic´ (20.1./22.1.)/Bryndís Guðjónsdóttir (21.1./23.1.) Maske Jutta Martens Kate Vera Bitter Übertitel Leopold Eibensteiner General Wingrave Yu Hsuan Cheng Technische Leitung Andreas Greiml/Thomas Hofmüller/Alexander Lährm Narrator Richard Glöckner Werkstättenleitung Thomas Hofmüller Kinderchor Antonella Hohenadler, Felix Knittel, Florian Kritzinger, Lennart Malm, Sophie Münch, Noah Obermair, Niklas Plasse, Lichtgestaltung Michael Becke Leonhard Radauer Tontechnik Susanne Gasselsberger Musikalische Leitung Gernot Sahler -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

The Four Seasons I

27 Season 2013-2014 Friday, November 29, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, November 30, at 8:00 Sunday, December 1, at 2:00 Richard Egarr Conductor and Harpsichord Giuliano Carmignola Violin Vivaldi The Four Seasons I. Spring, Concerto in E major, RV 269 a. Allegro b. Largo c. Allegro II. Summer, Concerto in G minor, RV 315 a. Allegro non molto b. Adagio alternating with Presto c. Presto III. Autumn, Concerto in F major, RV 293 a. Allegro b. Adagio molto c. Allegro IV. Winter, Concerto in F minor, RV 297 a. Allegro non molto b. Largo c. Allegro Intermission 28 Purcell Suite No. 1 from The Fairy Queen I. Prelude II. Rondeau III. Jig IV. Hornpipe V. Dance for the Fairies Haydn Symphony No. 101 in D major (“The Clock”) I. Adagio—Presto II. Andante III. Menuetto (Allegretto)—Trio—Menuetto da capo IV. Vivace This program runs approximately 1 hour, 40 minutes. The November 29 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 3 Story Title 29 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra community itself. His concerts to perform in China, in 1973 is one of the preeminent of diverse repertoire attract at the request of President orchestras in the world, sold-out houses, and he has Nixon, today The Philadelphia renowned for its distinctive established a regular forum Orchestra boasts a new sound, desired for its for connecting with concert- partnership with the National keen ability to capture the goers through Post-Concert Centre for the Performing hearts and imaginations of Conversations. -

Proquest Dissertations

Benjamin Britten's Nocturnal, Op. 70 for guitar: A novel approach to program music and variation structure Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alcaraz, Roberto Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 13:06:08 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/279989 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be f^ any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitlsd. Brolcen or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author dkl not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectk)ning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additkxial charge. -

Missa Brevis

Jacob de Haan Missa Brevis Partiture per coro misto Solo per uso personale 2 Ⓡ Ⓡ Soli Deo Hon Et Gl ia 3 Missa Brevis Indice dei contenuti Kyrie .............................................. .............. 4 Gloria............................................. ............... 6 Credo.............................................. .............. 11 Sanctus ............................................ .............. 18 Benedictus......................................... ................ 20 Agnus Dei .......................................... ............... 24 4 Missa Brevis Kyrie Coro Misto Jacob de Haan ø = 80 Soprano 11 2 2 Ky ri e e lei son, Ky ri e e lei son, f f Alto 11 2 2 11 Tenore 2 8 2 Kyf ri e e lei son, Kyf ri e e lei son, 11 Basso 2 2 19 S 3 Ky ri e e lei son, Ky ri e e lei son, 2 f f A 3 2 T 3 8 2 Kyf ri e e lei son, Kyf ri e e lei son, B 3 2 28 S 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 2 Ky ri e e 2 lei son, 2 Ky ri e e 2 lei son. 2Christe e 2 lei son, 2 ff f p A 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 T 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 8 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 Kyff ri e e lei son, Kyf ri e e lei son. Chrip ste e lei son, B 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 Coro Misto 5 34 S 3 2 3 2 2 Christe e 2 lei son, e lei son, 2 Chri ste Chri ste 2Christe e A ff ff ff 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 T 3 2 3 2 8 2 2 2 2 Christe e lei son, e lei son, Chriff ste Chriff ste Chriff ste e B 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 41 S 2 2 3 2 3 lei son. -

BENJAMIN BRITTEN a Ceremony of Carols IRELAND | BRIDGE | HOLST

BENJAMIN BRITTEN A Ceremony of Carols IRELAND | BRIDGE | HOLST Choir of Clare College, Cambridge Graham Ross FRANZ LISZT A Ceremony of Carols BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913-1976) ANONYMOUS, arr. BENJAMIN BRITTEN 1 | Venite exultemus Domino 4’11 12 | The Holly and the Ivy 3’36 for mixed choir and organ (1961) traditional folksong, arranged for mixed choir a cappella (1957) 2 | Te Deum in C 7’40 for mixed choir and organ (1934) BENJAMIN BRITTEN 3 | Jubilate Deo in C 2’30 13 | Sweet was the song the Virgin sung 2’45 for mixed choir and organ (1961) from Christ’s Nativity for soprano and mixed choir a cappella (1931) 4 | Deus in adjutorium meum intende 4’37 from This Way to the Tomb for mixed choir a cappella (1944-45) A Ceremony of Carols op. 28 (1942, rev. 1943) version for mixed choir and harp arranged by JULIUS HARRISON (1885-1963) 5 | A Hymn to the Virgin 3’23 for solo SATB and mixed choir a cappella (1930, rev. 1934) 14 | 1. Procession 1’18 6 | A Hymn of St Columba 2’01 15 | 2. Wolcum Yole! 1’21 for mixed choir and organ (1962) 16 | 3. There is no rose 2’27 7 | Hymn to St Peter op. 56a 5’57 17 | 4a. That yongë child 1’50 for mixed choir and organ (1955) 18 | 4b. Balulalow 1’18 19 | 5. As dew in Aprille 0’56 JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) 20 | 6. This little babe 1’24 8 | The Holy Boy 2’50 version for mixed choir a cappella (1941) 21 | 7. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1946

TANGLEWOOD— LENOX, MASSACHUSETTS THE Berkshire Music Center SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Director presents " ! cc PETER GRIMES" 11 by BENJAMIN BRITTEN Tuesday Evening, August 6 Wednesday Evening, August 7 Friday Evening, August 9 IP •*• 1946 W' !.«.w,a'i STEINWiV Since the time of Liszt, the Steinway has consistently been, year after year, the medium chosen by an overwhelming number of concert artists to express their art. Eugene List, Mischa El man and William Kroll, soloists of this Berk- shire Festival, use the Steinway. Significantly enough, the younger artists, the Masters of tomorrow, entrust their future to this world-famous piano — they cannot afford otherwise to en- danger their artistic careers. The Stein- way is, and ever has been, the Glory Road of the Immortals. M. STEINERT & SONS CO. : 162 BOYLSTON ST., BOSTON Jerome F. Murphy, President • Also Worcester and Springfield THEATRE-CONCERT HALL TANGLEWOOD (Between Stockbridge and Lenox, Massachusetts) Berkshire Music Center . SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Director Season 1946 Program Bulletin with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1946, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, InC. The trustees of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot President Henry B. Sawyer Vice-President Richard C. Paine Treasurer Philip R. Allen M. A. De Wolfe Howe John Nicholas Brown Jacob J. Kaplan Alvan T. Fuller Roger I. Lee Jerome D. Greene Bentley W. Warren N, Penrose Hallowell Raymond S. Wilkins Francis W. Hatch Oliver Wolcott TANGLEWOOD ADVISORY COMMITTEE Allan J. Blau G. Churchill Francis George P. Clayson Lawrence K. Miller Bruce Crane James T. Owens Henry W. Dwight Lester Roberts George W. Edman Whitney S. -

Britten's Acoustic Miracles in Noye's Fludde and Curlew River

Britten’s Acoustic Miracles in Noye’s Fludde and Curlew River A thesis submitted by Cole D. Swanson In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music TUFTS UNIVERSITY May 2017 Advisor: Alessandra Campana Readers: Joseph Auner Philip Rupprecht ii ABSTRACT Benjamin Britten sought to engage the English musical public through the creation of new theatrical genres that renewed, rather than simply reused, historical frameworks and religious gestures. I argue that Britten’s process in creating these genres and their representative works denotes an operation of theatrical and musical “re-enchantment,” returning spiritual and aesthetic resonance to the cultural relics of a shared British heritage. My study focuses particularly on how this process of renewal further enabled Britten to engage with the state of amateur and communal music participation in post-war England. His new, genre-bending works that I engage with represent conscious attempts to provide greater opportunities for amateur performance, as well cultivating sonically and thematically inclusive sound worlds. As such, Noye’s Fludde (1958) was designed as a means to revive the musical past while immersing the Aldeburgh Festival community in present musical performance through Anglican hymn singing. Curlew River (1964) stages a cultural encounter between the medieval past and the Japanese Nō theatre tradition, creating an atmosphere of sensory ritual that encourages sustained and empathetic listening. To explore these genre-bending works, this thesis considers how these musical and theatrical gestures to the past are reactions to the post-war revivalist environment as well as expressions of Britten’s own musical ethics and frustrations. -

Permian Basin String Quartet

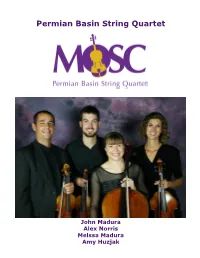

Permian Basin String Quartet John Madura Alex Norris Melssa Madura Amy Huzjak Described by the Odessa American as “a precise and authoritative sound” the Permian Basin String Quartet (PBSQ) is the resident quartet of the Midland-Odessa Symphony & Chorale and is comprised of the principal string players of the orchestra. The quartet members have developed a loyal audience and a reputation as a leading ensemble in the Permian Basin. The PBSQ has made recent appearances in Midland, Odessa, Abilene, Alpine, San Angelo, Big Spring, Lubbock, and Hobbs, NM. In 2015, the PBSQ was the featured guest artist on the Abilene Christian University (ACU) Tour as the soloists on Short Stories by Joel Puckett as well as gave the Texas premiers of several works by ACU visiting composer Hyunjoo Lee. In 2013 the PBSQ appeared in the Abilene Philharmonic Nocturne series as well as the Church of the Heavenly Rest Chamber series. The PBSQ frequently appears with the San Angelo State University Choir, has given masterclasses in Mexico and Lubbock, TX as well as appeared with Chamber Music Amarillo. In addition to performance, the PBSQ is very dedicated to music education. The PBSQ gives educational concerts at elementary schools in the Permian Basin throughout the year. In addition, the PBSQ serves as section coaches for several high school orchestras in the Permian Basin as well as the University of Texas-Permian Basin (UTPB) University Orchestra. The PBSQ has also partnered with UTPB as the faculty for the All-Region Summer Workshop as well as the Hartwick College Summer Festival in Oneonta, NY. -

Billy Budd Composer Biography: Benjamin Britten

Billy Budd Composer Biography: Benjamin Britten Britten was born, by happy coincidence, on St. Cecilia's Day, at the family home in Lowestoft, Suffolk, England. His father was a dentist. He was the youngest of four children, with a brother, Robert (1907), and two sisters, Barbara (1902) and Beth (1909). He was educated locally, and studied, first, piano, and then, later, viola, from private teachers. He began to compose as early as 1919, and after about 1922, composed steadily until his death. At a concert in 1927, conducted by composer Frank Bridge, he met Bridge, later showed him several of his compositions, and ultimately Bridge took him on as a private pupil. After two years at Gresham's School in Holt, Norfolk, he entered the Royal College of Music in London (1930) where he studied composition with John Ireland and piano with Arthur Benjamin. During his stay at the RCM he won several prizes for his compositions. He completed a choral work, A Boy was Born, in 1933; at a rehearsal for a broadcast performance of the work by the BBC Singers, he met tenor Peter Pears, the beginning of a lifelong personal and professional relationship. (Many of Britten's solo songs, choral and operatic works feature the tenor voice, and Pears was the designated soloist at many of their premieres.) From about 1935 until the beginning of World War II, Britten did a great deal of composing for the GPO Film Unit, for BBC Radio, and for small, usually left-wing, theater groups in London. During this period he met and worked frequently with the poet W.