Healing Journey Becoming Authentic Workbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Metaphysical Thought

ISSN 2577-6460 (Print) ISSN 2577-6479 (Online) Journal of Metaphysical Thought Volume I | Issue 1 July 2018 Mindful Services, LLC Emory, VA JOURNAL OF METAPHYSICAL Contents THOUGHT FRONT MATTER ISSN: Page 5 2577-6460 (Print) Editor’s Note 2577-6479 (Online) Chris Anama-Green Call for Articles (Volume I, Issue 2) Page 7 Published by: Editorial staff Mindful Services, LLC P.O. Box 155 Emory, VA ARTICLES Editor-in-Chief: These Perilous Times Page 8 Chris Anama-Green Joanna Neff [email protected] The Power of Forgiveness to Heal Page 16 Relationships Editorial Board: Jenine Marie Howry D. Ann Gordon Scott D. Vaughn The Misunderstanding between Page 24 Colleen D. Fletcher Schizophrenia and Clairaudience William M. Sloane Philippa Sue Richardson Cover: East-meets-west: How the Dhammapada Page 28 Courtesy of Canva Influenced the New Thought Movement Chris Anama-Green Aims and Scope: With an emphasis on practice- PERSPECTIVES based and research-based articles, the Journal peer Does Reincarnation Matter? Page 34 reviews and publishes practice- J. Joy Maestas based articles, case studies, editorials, original research, A Metaphysical Perspective on Prayer Page 36 "brief" articles, and reviews. Cindy Paulos Journal of Metaphysical Thought covers a range of disciplines, including metaphysics, consciousness studies, New Thought principles, spirituality, and metaphysical theology. Journal of Metaphysical Thought is published by twice each year. Unless otherwise stated, all articles in this publication are licensed under a Cre- ative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. We ask that you credit the author and the journal when sharing any article in this issue. www.metaphysicalthought.com The articles in this journal are thoroughly reviewed and edited prior to publica- tion. -

Camphill Correspondence March/April 2005

March/April 2005 CAMPHILL CORRESPONDENCE e Balinese have an essential concept of Wbalance. It’s the Tri Hita Karan, the con- cept of triple harmonious balance. The balance between God and humanity; humanity with itself; and humanity with the environment. This places us all in a universe of common understanding. It is not only nuclear bombs that have fallout. It is our job to minimize this fallout for our people and our guests from around the world. Who did this? This is not such an important question for us to discuss. Why this happened —maybe this is more worthy of thought. What can we do to create beauty from this tragedy and come to an understanding where nobody feels the need to make such a statement again? This is important. That is the basis from which we can embrace everyone as a brother, every- one as a sister. It’s a period of uncertainty, a period of change. It is also an opportunity for us to move together into a better future—a future where we embrace Mt. LeFroy, Lawren Harris all of humanity, in the knowledge that we all look and smell the same when we are burnt. Victims of this tragedy are from all over the world. The past is not signifi cant. It is the future that is important. This is the time to bring our values, our empathy, to society and the world at large. To care; to love. We want to return to our lives. Please help us realize this wish. Why seek retribution from people who are acting as they see fi t? These people are misguided from our point of view. -

St Francis Library for Peace Items by Title - with Multimedia and Call Number INVENTORY

18 Aug 2015 1:24 PM St Francis Library For Peace Items by Title - with Multimedia and Call Number INVENTORY Image Title Author Call Number Jerusalem : Center of the World 12 Angry Men Lumet, Sidney (Director) The 12-Step Buddhist : Enhance Recovery From Littlejohn, Darren 294.3 LIT Any Addiction 0 1491 : New Revelations Of The Americas Before Mann, Charles C. 970.011 Man Columbus 1st ed. 20 Feet from Stardom Neville, Morgan (director) 20 Romantic Instrumentals Various 20-minute Retreats : Revive Your Spirits In Just Harris, Rachel. / Philip Lief 158.12 Har Minutes A Day With Simple, Self-led Exercises Group. 1st ed. 2030 : Confronting Thermageddon In Our Lifetime Hunter, Robert, 1941- 363.7 Hun 21 Grams Inarritu, AlejandroGonzalez (director) 21st Century Sex Slaves 26 Happy Honky Tonk Memories Jasen, Dave ResourceMate® 3.0 Pre-Circulation Start-up Page 1 18 Aug 2015 1:24 PM St Francis Library For Peace Items by Title - with Multimedia and Call Number INVENTORY Image Title Author Call Number 30 Years Of National Geographic Specials DVD Nye, Barry / Nye, Barry / DVD Video Willumsen, Gail 365 Ways To Save the Earth Bourseiller, Philippe 779 Bou The 3rd Alternative : Solving Life's Most Difficult Covey, Stephen R. 158 COV Problems 1 **40-day Journey With Joan Chittister (40-day Chittister, Joan D. / Lanzetta, 248 Chi Journey Series.) Beverly 40-day Journey With Madeleine L' Engle (The 40 L'Engle, Madeleine. / Anders, BOOKS 248 L'E Day Journey Series) Isabel, 1946- 40-day Journey With Maya Angelou (40-day Angelou, Maya. / French, BOOKS 248 Ang Journey Series.) Henry F. -

The Science of Proving God’S Existence

The Science of Proving God’s Existence Yoga, God and Enlightenment. The Path to Inner Happiness. What is God? Newest Findings. Near-death Research. Reincarnation Research. Amma embraces the World. Darshan with Mutter Meera. The Great Atheist Debate 2009. Reform the Church. The Unity of all Religions. Nils Horn Copyright: 2010 Nils Horn, Hamburg, Germany. Many thanks for translation to Megan Leo. Private (non-commercial) distribution is permitted. Proof of God’s Existence? 3 What is God? Threefold Proof of God The Path to Inner Happiness Levels of Happiness Jesus and the Sermon on the Mount The Search for Happiness The Ten Points of Happiness Newest Findings 14 American Physicist Amit Goswami Interview with Amit Goswami What Was There Before the Big Bang? The Three Worlds Model Near-death Research 19 German Television Program on Near-death Research The arguments of the atheists Proof of Life After Death The Death of the 16th Karmapa Discussion of the Death of the Karmapa Reincarnation Research 27 Earlier Life Along the Way of the Yogi Yogi without Eating Parapsychology Are there Such Things as Ghosts? The Other Side 35 The Four Astral Worlds The Three Light Worlds The Eight Heavens Seventh Heaven Meditation Is There a Hell? 41 Is There a Devil? Rage as Hell Depression as Hell Going Through Difficult Times The Astral Journey 45 Two Ways to Paradise The Jellyfish Dream Swami Muktananda Nils’ Life as a Yogi 49 The Five Duties The Spritual Daily Routine The Way of All-Encompassing Love Amma embraces the World Darshan with Mutter Meera The -

Unity Business Directory 2015 COMPLETE BOOK.Indb

ART AND DESIGN | BEAUTY | ENTERTAINMENT & DINING | HEALTH | PROFESSIONAL SERVICES | SHOPPING | SPIRITUAL WELLNESS | YOUTH & COMMUNITY SERVICES The riskiest financial move is doing nothing. Your wealth plan should keep up with the changing circumstances of your life, as well as with the cycles in the financial markets. A new career, a new grandchild, a new business, a significant shift in your portfolio — any of these events could necessitate a fresh look at your strategy. As a Morgan Stanley Financial Advisor, I can work with Gwen Cohen Investment Consultant you to develop a plan and then help you manage your First Vice President investments and assets through life’s changes. Call today Wealth Advisor to arrange an appointment. We’ll work together to plan for what may come. 70 West Madison St., Suite 5450 Chicago, IL 60602 312-443-6527 [email protected] www.morganstanelyfa.com/gwen. cohen © 2013 Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC. Member SIPC. CRC588400 (12/12) CS 7338862 MAR014 04/13 Table of Contents Art and Design .................................................. 5 Beauty .............................................................11 Entertainment & Dining ..................................13 Health ..............................................................17 Professional Services .....................................21 Shopping ......................................................... 27 Spiritual Wellness ...........................................29 Youth & Community Services ........................33 ART AND DESIGN -

Journeys of Purpose : an Ontology of Spirituality Through Work in Memory, Imagination, and Authenticity Therese M

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2008 Journeys of purpose : an ontology of spirituality through work in memory, imagination, and authenticity Therese M. Madden Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Madden, Therese M., "Journeys of purpose : an ontology of spirituality through work in memory, imagination, and authenticity" (2008). Doctoral Dissertations. 189. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/189 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO JOURNEYS OF PURPOSE AN ONTOLOGY OF SPIRITUALITY THROUGH WORK IN MEMORY, IMAGINATION, AND AUTHENTICITY A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Department of Leadership Studies Organization and Leadership Program In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education THERESE M. MADDEN SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA May 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………….1 CHAPTER ONE – INTRODUCTION Introduction……………………………………………………………………. -

Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs Vol.4: S - Z

Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs vol.4: S - Z © Neuss / Germany: Bruno Buike 2017 Buike Music and Science [email protected] BBWV E30 Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs - vol.4: S - Z Neuss: Bruno Buike 2017 CONTENT Vol. 1 A-D 273 p. Vol. 2 E-K 271 p. Vol. 3 L-R 263 p. Vol. 4 S-Z 239 p. Appr. 21.000 title entries - total 1046 p. ---xxx--- 1. Dies ist ein wissenschaftliches Projekt ohne kommerzielle Interessen. 2. Wer finanzielle Forderungen gegen dieses Projekt erhebt, dessen Beitrag und Name werden in der nächsten Auflage gelöscht. 3. Das Projekt wurde gefördert von der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Sozialamt Neuss. 4. Rechtschreibfehler zu unterlassen, konnte ich meinem Computer trotz jahrelanger Versuche nicht beibringen. Im Gegenteil: Das Biest fügt immer wieder neue Fehler ein, wo vorher keine waren! 1. This is a scientific project without commercial interests, that is not in bookstores, but free in Internet. 2. Financial and legal claims against this project, will result in the contribution and the name of contributor in the next edition canceled. 3. This project has been sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany, Department for Social Benefits, city of Neuss. 4. Correct spelling and orthography is subject of a constant fight between me and my computer – AND THE SOFTWARE in use – and normally the other side is the winning party! Editor`s note – Vorwort des Herausgebers preface 1 ENGLISH SHORT PREFACE „Paul Smith“ is a FAKE-IDENTY behind which very probably is a COLLCETIVE of writers and researchers, using a more RATIONAL and SOBER approach towards the complex of Rennes-le-Chateau and to related complex of „Priory of Sion“ (Prieure de Sion of Pierre Plantard, Geradrd de Sede, Phlippe de Cherisey, Jean-Luc Chaumeil and others). -

The Dream Refinery: Psychics, Spirituality and Hollywood in Los Angeles

The Dream Refinery: Psychics, Spirituality and Hollywood in Los Angeles by Spencer Dwight Orey Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Louise Meintjes, Supervisor ___________________________ Engseng Ho ___________________________ Charles Piot ___________________________ Priscilla Wald Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 ABSTRACT The Dream Refinery: Psychics, Spirituality and Hollywood in Los Angeles by Spencer Dwight Orey Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Louise Meintjes, Supervisor ___________________________ Engseng Ho ___________________________ Charles Piot ___________________________ Priscilla Wald An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 Copyright by Spencer Dwight Orey 2016 Abstract This ethnography examines the relationship between mass-mediated aspirations and spiritual practice in Los Angeles. Creative workers like actors, producers, and writers come to L.A. to pursue dreams of stardom, especially in the Hollywood film and television media industries. For most, a “big break” into their chosen field remains perpetually out of reach despite their constant efforts. Expensive workshops like acting classes, networking events, and chance encounters are seen as keys to Hollywood success. Within this world, rumors swirl of big breaks for devotees in the city’s spiritual and religious organizations. For others, it is in consultations with local spiritual advisors like professional psychics that they navigate everyday decisions of how to achieve success in Hollywood. -

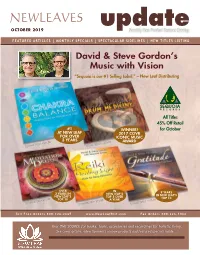

David & Steve Gordon's Music with Vision

OCTOBER 2019 Monthly New Product Feature Catalog FEATURED ARTICLES | MONTHLY SPECIALS | SPECTACULAR SIDELINES | NEW TITLES LISTING David & Steve Gordon’s Music with Vision “Sequoia is our #1 Selling Label.” – New Leaf Distributing All Titles 45% Off Retail #1 WINNER! for October AT NEW LEAF 2017 COVR FOR OVER ICONIC MUSIC 3 YEARS 8 .98 AWARD • $15.9 0 • $15 771221 478362 727044 72704 OVER IN 9 YEARS 3 YEARS IN NEW LEAF’S NEW LEAF’S IN NEW LEAF’S TOP 5 OVER TOP 10 $15.98 TOP 10 8 A YEAR 5.98 0223 • • $15.9 27 • $1 704478 792820 447709 72 727044 7270 Toll Free Orders 800-326-2665 www.NewLeafDist.com Fax Orders 800-326-1066 Your ONE SOURCE for books, tools, accessories and recordings for holistic living. See cover article, advertisements on new products and featured specials inside... ENTRAIN YOUR BRAIN, TUNE YOUR BIO-FIELD, SOOTHE YOUR SOUL with #1 Best-Selling Sound Healer STEVEN HALPERN “ Steven Halpern’s music has uplifted a generation of seekers. He has created a soundtrack for our evolutionary journey.” — Marianne Williamson, “A Return to Love” Sound Healer, Founding Father of New Age music • Access alpha and theta (see article, this issue) brain states for enhanced ECHOES OF A DREAM healing and meditation NEW! • Features Kristin Hoffmann • Promotes mindful (goddess vocals) and awareness… David Darling, cello just by listening • Sure to delight long time and new Halpern fans • Relax and fall asleep… • Tuned to 432 Hz for optimal healing at the speed of sound “Breathtaking sound quality, sensual • Breakthrough support 0-9379181112-2 and evocative melodies. -

New Age Tower of Babel Copyright 2008 by David W

The New Age Tower of Babel Copyright 2008 by David W. Cloud ISBN 978-1-58318-111-9 Published by Way of Life Literature P.O. Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061 866-295-4143 (toll free) • [email protected] (e-mail) http://www.wayoflife.org (web site) Canada: Bethel Baptist Church, 4212 Campbell St. N., London, Ont. N6P 1A6 • 519-652-2619 (voice) • 519-652-0056 (fax) • [email protected] (e-mail) Printed in Canada by Bethel Baptist Print Ministry 2 CONTENTS I. The New Age’s Vain Dream ....................................................5 II. Oprah Winfrey: The New Age High Priestess ......................10 III. My Experience in the New Age ..........................................27 IV. The New Age and the Mystery of Iniquity ..........................32 V. What Is the New Age? ..........................................................36 VI. The Origin of the New Age .................................................47 VII. How the New Age Evolved over the Past 100 Years .........61 The Stage Was Set at the Turn of the 20th Century The Mind Science Cults ................................................62 Christian Science ...........................................................64 Unity School of Christianity .........................................69 Helena Blavatsky and Theosophy .................................72 Alice Bailey ...................................................................80 The New Thought Positive-Confession Movement ......85 Aldous Huxley ..............................................................91 Alan -

False-Religions.Pdf

False Religions False Religions Scientology Founder • Scientology was founded by L. Ron Hubbard • 1950 – Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health • 1953 – Hubbard founded the first Church of Scientology in New Jersey Religion? • Hubbard once described Scientology as “the Western Anglicized continuance of many earlier forms of wisdom.” • Combines Confucianism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Gnosticism, teachings of Jesus, and writings of William James, Sigmund Freud, and Friedrich Nietzsche. God and the World • We are free to interpret God as we wish. • God in described in terms like Nature, Infinity, the Eighth Dynamic, and All Theta. • Basic principle: “The thetan is the source of all creation and life itself.” God and the World • MEST is the material, energy, space, and time of our universe. • Hubbard says that MEST is the projection of a vast number of spirit creatures called thetans who were bored with the non- material existence and decided to emanate a universe to play “The Game of Life.” Human Nature • People return through reincarnation, inhabiting different bodies. • In each new body, their “engrams” (sensory impressions stored in the mind) from past lives stick with them and cause more problems with each new reincarnation. Salvation • Scientology offers us a plan for self improvement. • Through hard work and auditing with an E-meter you can discover the truth and reach a god-like existence. Scientology E-meter Salvation • Through successful auditing, you can become an Operating Thetan and wear an OT bracelet. • This is a sign that you have reached “total spiritual independence and serenity.” History • Seventy five million years ago an evil leader called Xenu decided to wipe out most of the population of a galactic confederacy consisting of 26 stars and 76 planets. -

Welcoming the Stranger: a Youth Study on Migration

Welcoming the Stranger: A Youth Study on Migration by Cindy Klick Table of Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Session 1. ................................................................................................................................................2 Immigration: What Does it Mean and How Does it Affect Me? Session 2. ..............................................................................................................................................12 The Bible: From Forty Years in the Wilderness to the Journeys of Paul Session 3. ..............................................................................................................................................22 My Family Tree: Roots and Wings Welcoming the Stranger: A Youth Study on Migration by Cindy Klick, © 2013 United Methodist Women. All rights reserved. Session 4. ..............................................................................................................................................33 No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, elec- Searching for Home: Historic Perspective on the Migration of the Roma People tronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed