Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies Teaching English Language and Literature for Secondary Schools Petr Husseini Nick Cave’s Lyrics in Official and Amateur Czech Translations Master‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Renata Kamenická, Ph.D. 2009 Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. .................................................. Author‟s signature 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Mgr. Renata Kamenická, Ph.D., for her kind help, support and valuable advice. 3 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 5 1. Translation of Lyrics and Poetry .............................................................................. 9 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................... 9 1.2 General Nature of Lyrics and Poetry ........................................................ 11 1.3 Tradition of Lyrics Translated into Czech ............................................... 17 1.4 Conclusion ................................................................................................... 20 2. Nick Cave’s Lyrics in King Ink and King Ink II ................................................... 22 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 22 -

Bollettino Novità

Bollettino Novità Biblioteca del Centro Culturale Polifunzionale "Gino Baratta" di Mantova 4' trimestre 2019 Biblioteca del Centro Culturale Polifunzionale "Gino Baratta" Bollettino novità 4' trimestre 2019 1 Le *100 bandiere che raccontano il mondo / DVD 3 Tim Marshall ; traduzione di Roberto Merlini. - Milano : Garzanti, 2019. - 298 p., [8] carte 3 The *100. La seconda stagione completa / di tav. : ill. ; 23 cm [creato da Jason Rothenberg]. - Milano : inv. 178447 Warner Bros. Entertainment Italia, 2016. - 4 DVD-Video (ca. 674 min. compless.) -.929.9209.MAR.TIM color., sonoro ; in contenitore, 19 cm. 1 v ((Caratteristiche tecniche: regione 2; 16:9 FF, adatto a ogni tipo di televisore; audio 2 The *100. La prima stagione completa / Dolby digital 5.1. - Titolo del contenitore. [creato da Jason Rothenberg]. - Milano : - Produzione televisiva USA 2014-2015. - Warner Bros. Entertainment Italia, 2014. Interpreti: Eliza Taylor, Bob Morley, Marie - 3 DVD-Video (circa 522 min) : Avgeropoulos. - Lingue: italiano, inglese; color., sonoro ; in contenitore, 19 cm. sottotitoli: italiano, inglese per non udenti ((Caratteristiche tecniche: regione 2; video + 1: The *100. 2. : episodi 1-4 / [creato 16:9, 1.85:1 adatto a ogni tipo di tv; da Jason Rothenberg]. - Milano : Warner audio Dolby digital 5.1, 2.0. - Titolo Bros. entertainment Italia, 2016. - 1 DVD- del contenitore. - Prima stagione in Video (ca. 172 min.) ; in contenitore, 13 episodi del 2014 della serie TV, 19 cm. ((Contiene: I 48 ; Una scoperta produzione USA. - Interpreti: Eliza Taylor, agghiacciante ; Oltre lapaura ; Verso la città Isaiah Washington, Thomas McDonell. - della luce. Lingue: italiano, inglese, francese, tedesco; inv. 180041 sottotitoli: italiano, inglese, tedesco per non udenti, inglese per non udenti, tedesco, DVFIC.HUNDR.1 francese, olandese, greco DVD 1 + 1: The *100'. -

Nightshiftmag.Co.Uk @Nightshiftmag Nightshiftmag Nightshiftmag.Co.Uk Free Every Month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 299 September Oxford’S Music Magazine 2021

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 299 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2021 Gig, Interrupted Meet the the artists born in lockdown finally coming to a venue near you! Also in this comeback issue: Gigs are back - what now for Oxford music? THE AUGUST LIST return Introducing JODY & THE JERMS What’s my line? - jobs in local music NEWS HELLO EVERYONE, Festival, The O2 Academy, The and welcome to back to the world Bullingdon, Truck Store and Fyrefly of Nightshift. photography. The amount raised You all know what’s been from thousands of people means the happening in the world, so there’s magazine is back and secure for at not much point going over it all least the next couple of years. again but fair to say live music, and So we can get to what we love grassroots live music in particular, most: championing new Oxford has been hit particularly hard by the artists, challenging them to be the Covid pandemic. Gigs were among best they can be, encouraging more the first things to be shut down people to support live music in the back in March 2020 and they’ve city and beyond and making sure been among the very last things to you know exactly what’s going be allowed back, while the festival on where and when with the most WHILE THE COVID PANDEMIC had a widespread impact on circuit has been decimated over the comprehensive local gig guide Oxford’s live music scene, it’s biggest casualty is The Wheatsheaf, last two summers. -

DIALOGUE DIALOGUE PO Box 381209 Cambridge, MA 02238 Electronic Service Requested

DIALOGUE DIALOGUE PO Box 381209 Cambridge, MA 02238 electronic service requested DIALOGUE a journal of mormon thought 49.4 winter 2016 49.4 EDITORS EDITOR Boyd Jay Petersen, Provo, UT ASSOCIATE EDITOR David W. Scott, Lehi, UT WEB EDITOR Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT DIALOGUE FICTION Julie Nichols, Orem, UT POETRY Darlene Young, South Jordan, UT a journal of mormon thought REVIEWS (non-fiction) John Hatch, Salt Lake City, UT REVIEWS (literature) Andrew Hall, Fukuoka, Japan INTERNATIONAL Gina Colvin, Christchurch, New Zealand Carter Charles, Bordeaux, France POLITICAL Russell Arben Fox, Wichita, KS HISTORY Sheree Maxwell Bench, Pleasant Grove, UT SCIENCE Steven Peck, Provo, UT FILM & THEATRE Eric Samuelson, Provo, UT PHILOSOPHY/THEOLOGY Brian Birch, Draper, UT ART Andrea Davis, Orem, UT IN THE NEXT ISSUE Brad Kramer, Murray, UT Brad Cook, “Pre-Mortality in Mystical Islam” BUSINESS & PRODUCTION STAFF BUSINESS MANAGER Mariya Manzhos, Cambridge, MA PRODUCTION MANAGER Jenny Webb, Huntsville, AL Allen Hansen & Walker Wright, “Worship through COPY EDITORS Sarah Moore, Madison, AL Corporeality in Hasidism and Mormonism” Richelle Wilson, Madison, WI INTERNS Stocktcon Carter, Provo, UT Nathan Tucker, Provo, UT Fiction from William Morris Geoff Griffin, Provo, UT Christian D. Van Dyke, Provo, UT Fiction from R. A. Christmas Ellen Draper, Provo, UT EDITORIAL BOARD Lavina Fielding Anderson, Salt Lake City, UT William Morris, Minneapolis, MN Mary L. Bradford, Landsdowne, VA Michael Nielsen, Statesboro, GA Claudia Bushman, New York, NY Nathan B. Oman, Williamsburg, VA Daniel Dwyer, Albany, NY Thomas F. Rogers, Bountiful, UT Ignacio M. Garcia, Provo, UT Mathew Schmalz, Worcester, MA Join our DIALOGUE! Brian M. Hauglid, Spanish Fork, UT David W. -

Nick Cave, Un Concerto a Pagamento in Streaming E Senza Repliche LINK

22/07/2020 14:40 Sito Web rep.repubblica.it La proprietà intellettuale è riconducibile alla fonte specificata in testa pagina. Il ritaglio stampa da intendersi per uso privato Nick Cave, un concerto a pagamento in streaming e senza repliche LINK: https://rep.repubblica.it/ws/detail/generale/2020/07/22/news/nick_cave-262623517/ Nick Cave, un concerto a singolare, nel senso pieno altri l'artista australiano non pagamento in streaming e del termine, perché sarà in ha fatto live streaming da senza repliche 22 Luglio scena da solo, casa nelle settimane 2020 L'artista australiano accompagnato dal passate, fino a quando, in protagonista di uno show pianoforte, senza i giugno, non ha registrato registrato senza band e a fedelissimi Bad Seeds, per questa ora e mezza di porte chiuse a Londra che interpretare molte canzoni musica dal vivo. Più che un andrà in onda una sola del suo straordinario concerto è una performance volta: la fruizione sarà repertorio, brani vecchi e artistica, perché non c'è identica a quello di un live nuovi, alcuni eseguiti per la pubblico, perché sembra vero e proprio di ERNESTO prima volta dal vivo, tutto fuori dal tempo e dallo ASSANTE {{MediaVoti}} / compresi brani tratti dai i spazio, come si vede nella 5 Salva Il 23 luglio, alle 21, primi lavori con Bad Seeds clip che ha presentato si potrà assistere on line e Grinderman fino all'ultimo l'evento, perché Cave è sulla app del sito Dice.Fm a album con la band, il completamente solo "Idiot Prayer: Nick Cave bellissimo e drammatico nell'esecuzione di ventidue Alone at Alexandra Palace", Ghosteen. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Interview with Asa Taccone from Electric Guest

Interview with Asa Taccone from Electric Guest By artistically fusing both vintage and contemporary aesthetics, Los Angeles indie soul act Electric Guest brings a unique groove. Frontman Asa Taccone has a velvety and soulful voice that reaches different levels of vocal range while Matthew “Cornbread” Compton creates electronically fueled beats and rhythms. It’s a melding of Motown swagger with modern pop and an abundance of substance. While a lot of their contemporaries seem to lack something, Taccone and Compton convey sounds that come complete in full force. It’s what makes this duo one of the top up-and-coming music groups of the 2010s. With Brooklyn indie pop wonders Chaos Chaos opening things up, Electric Guest will take the upstairs stage at the Columbus Theatre in Providence’s west end on March 4. Before the show I had a chat with Taccone about the band’s latest album, Plural, the songwriting partnership he has with Compton, growing tired of hip-hop, being a former writer for “Saturday Night Live” and what we can expect from Electric Guest for the rest of the year. Rob Duguay: Electric Guest are Plural on February 17. It’s the follow-up to the band’s critically acclaimed debut, Mondo, that came out in 2012. Did you feel any pressure while making the new album in the studio and what did you do differently with Plural versus what you did with Mondo? Asa Taccone: There was definitely pressure. It was part of the reason why it took so damn long for Plural to come out. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

NO RISK DISC Greentea Peng What’S New

4 juni 2021 - nr. 378 Het blad van/voor muziekliefhebbers NO RISK DISC Greentea Peng What’s New Billie Marten Flora Fauna ‘Flora Fauna’ is het derde album van singer/songwriter Billie Marten. Na twee akoestische folk albums, heeft ze haar kenmerkende sound uitgebreid met een sterke ruggengraat van bas en ritme. De liedjes markeren een periode van persoonlijke onafhankelijkheid voor Marten, terwijl ze leerde om goed voor zichzelf te zorgen en zich los te maken uit giftige relaties. Release: 21 mei James All the Colours of You ‘All the Colours of You’ is het zestiende studioalbum van de Britse rockband James. Het album is geproduceerd door de met een Grammy bekroonde Jacknife Lee (U2, REM, Taylor Swift, Snow Patrol, The Killers). Hij zorgde voor een frisse blik en een andere benadering, waardoor ‘All the Colours of You’ een fris en festivalklaar geluid heeft. Release: 4 juni Rise Against Nowhere Generation NO ‘Nowhere Generation’ is het negende studioalbum van de Amerikaanse rockband Rise Against. De muziek van de band is gevormd door het activisme en het gevoel van sociale RISK rechtvaardigheid van de bandleden. Dit zijn dan ook elementen die centraal staan in ‘Nowhere Generation’. DISC GREENTEA PENG Release: 4 juni Man Made (Universal) jeugd die niets wil voelen, maar tegelijkertijd LP, CD alles voelt en waarbij Peng zichzelf verliest in Gaspard Augé Greentea Peng is de artiestennaam van de in Zuid- antidepressiva. Die eerlijkheid fascineert. Pengs Escapades Londen geboren zangeres Aria Wells. De 26-jarige teksten zijn donker en persoonlijk en gaan over ‘Escapades’ is het debuutalbum van Gaspard Augé, vooral bekend Peng is met haar vele tatoeages een opvallende haar hoopvolle verlangen naar eenheid in een als de helft van Justice: het duo dat rock en rave verenigde in verschijning, maar meer nog imponeert ze door wereld vol patriarchale structuren, marginalisatie het midden van de jaren 2000. -

Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave

Student ID: XXXXXX ENGL3372: Dissertation Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the Lyrics of Nick Cave Table of Contents Introduction 2 Chapter One – ‘I went on down the road’: Cave and the holy blues 4 Chapter Two – ‘I got the abattoir blues’: Cave and the contemporary 15 Chapter Three – ‘Can you feel my heart beat?’: Cave and redemptive feeling 25 Conclusion 38 Bibliography 39 Appendix 44 Student ID: ENGL3372: Dissertation 12 May 2014 Faith, Selfhood and the Blues in the lyrics of Nick Cave Supervisor: Dr. Richard Brown INTRODUCTION And I only am escaped to tell thee. So runs the epigraph, taken from the Biblical book of Job, to the Australian songwriter Nick Cave’s collected lyrics.1 Using such a quotation invites anyone who listens to Cave’s songs to see them as instructive addresses, a feeling compounded by an on-record intensity matched by few in the history of popular music. From his earliest work in the late 1970s with his bands The Boys Next Door and The Birthday Party up to his most recent releases with long- time collaborators The Bad Seeds, it appears that he is intent on spreading some sort of message. This essay charts how Cave’s songs, which as Robert Eaglestone notes take religion as ‘a primary discourse that structures and shapes others’,2 consistently use the blues as a platform from which to deliver his dispatches. The first chapter draws particularly on recent writing by Andrew Warnes and Adam Gussow to elucidate why Cave’s earlier songs have the blues and his Christian faith dovetailing so frequently. -

Laura Harker & Paul Sullivan on Nick Cave and the 80S East

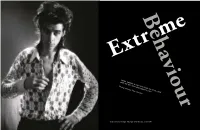

Behaviour 11 Extr me LaurA HArKer & PAul SullIvAn On Nick CAve AnD THe 80S East KreuzBerg SCene Photography by Peter gruchot 10 ecords), 24 April 1986 Studio session for the single ‘The Singer’ (Mute r Cutting a discreet diagonal between Kottbusser Tor and Oranienplatz, Dresdener Straße is one of the streets that provides blissful respite from east Kreuzberg’s constant hustle and bustle. Here, the noise of the traffic recedes and the street’s charms surge subtly into focus: fashion boutiques and indie cafés tucked into the ground floors of 19th Century Altbauten, the elegantly run-down Kino Babylon and the dark and seductive cocktail bar Würgeengel, the “exterminating angel”, a name borrowed from a surrealist film by luis Buñuel. It all looked very different in the 80s of course, when the Berlin Wall stood just under a kilometre away and the façades of these houses – now expensively renovated and worth a pretty penny – were still pockmarked by World War Two bulletholes. Mostly devoid of baths, the interiors heated by coal, their inhabitants – mostly Turkish immigrants – shivered and shuffled their way through the Berlin winter. 12 13 It was during this pre-Wende milieu that a tall, skinny and largely unknown Australian musician named Nicholas Edward Cave moved into no. 11. Aside from brief spells in apartments on naumannstraße (Schöneberg), yorckstraße, and nearby Oranienstraße, Cave spent the bulk of his seven on-and-off years in Berlin living in a tiny apartment alongside filmmaker and musician Christoph Dreher, founder of local outfit Die Haut. It was in this house that Cave wrote the lyrics and music for several Birthday Party and Bad Seeds albums, penned his debut novel (And The Ass Saw The Angel) and wielded a sizeable influence over Kreuzberg’s burgeoning post-punk scene. -

Pokémon GO Saad Ahmed Gives the Dirt on Why Pokémon GO Isn’T Fun and Was Doomed to Fail

ISSUE 1654 ...the issue that wasn’t meant to but became an anti-Trump issue FRIDAY 27 JANUARY 2017 THE STUDENT NEWSPAPER OF IMPERIAL COLLEGE LONDON elix Students f demand better Careers Service RESIST PAGE 3 News Imperial students march against Trump PAGE 6 News To protest or not to protest? PAGE 8 Comment Trident | They lied to us PAGE 10 Comment Barry! Grab the boys some poppers will you? The state’s fight against legal highs PAGE 27 Millennials 2 felixonline.co.uk [email protected] Friday 27 January 2017 felix EDITORIAL Resistance is not futile. We think. ell we honestly tried – you Also jumping on the bandwagon, every know, taking a break from the >>insert descriptive term of choice<< in the US is doom and gloom. With the end proposing backwards bills such as bills “to repeal of 2016, we were eager to turn the Environmental Protection Agency’s most over a new leaf, start anew with recent rule for new residential wood heaters” starry eyes full of hope for the or bills proclaiming “each human life begins Wfuture. But since Trump’s inauguration last Friday, it’s with fertilization” or bills requiring “pipelines just been an onslaught of bad news, dumb news and regulated by the Secretary of Transportation to outright ridiculous news. Since Friday, the Donald be made of steel that is produced in the United has broken Obamacare, has withdrawn from the States” or God knows what. Transpacific Partnership, has reintroduced the Mexico Meanwhile the Brexit saga is dragging on City Policy which effectively strips federal financial and on.