Activities from the Informal Economy: Farmer and Small Trader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICICI Bank Launches 'Social Pay'

VOL-14 ISSUE -6 CONTENTS Editor 2018 Commonwealth Games Ayushman Bharat : National Health Protection Mission N.K. Jain Advisors Neeraj Chabra K.C.Gupta Registered Office Mahendra Publication Pvt. Ltd. 103, Pragatideep Building, Padma Awards 2018 Pulitzer Prize 2018 Plot No. 08, Laxminagar, District Centre, New Delhi - 110092 TIN-09350038898 w.e.f. 12-06-2014 Branch Office Mahendra Publication Pvt. Ltd. E-42,43,44, Sector-7, Noida (U.P.) Interview 5 For queries regarding Current Affairs - One Liner 6-9 promotion, distribution & Spotlight 10 advertisement, contact:- [email protected] The People 11-16 Ph.: 09208037962 News Bites 18-56 Owned, printed & published by World of English - Etymology 57 N.K. Jain Designation : Who's Who 61 103, Pragatideep Building, 2018 Commonwealth Games 63-65 Plot No. 08, Laxminagar, District Centre, New Delhi - 110092 Ayushman Bharat : National Health Protection Mission 66-67 Please send your suggestions and Padma Awards 2018 68-70 grievances to:- Mahendra Publication Pvt. Ltd. Pulitzer Prize 2018 71-72 CP-9, Vijayant Khand, Que Tm - General Awareness 74-84 Gomti Nagar Lucknow - 226010 E-mail:[email protected] RO/ARO 2018 : UPPSC - Solved Paper 2018 85-102 © Copyright Reserved SBI Clerk Pre - Model Paper 2018 103-114 # No part of this issue can be printed in whole or in part without the written permission of the publishers. # All the disputes are subject to Delhi jurisdiction only. Mahendra Publication Pvt. Ltd. Editorial "Courage is what it takes to stand up and speak; courage is also what it takes to sit down and listen." - Winston Churchill Dear Aspirants, Once again we are pleased to present you the 'June 2018' Edition of our very own 'Masters in Current Affairs'. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Global, Regional, and National Age-Sex-Specific Mortality and Life Expectancy, 1950-2017: a Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Civil & Environmental Engineering Faculty Publications Civil & Environmental Engineering 11-10-2018 Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 Ali S. Akanda University of Rhode Island, [email protected] et al Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cve_facpubs Citation/Publisher Attribution Akanda, Ali S., and et al. "Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017." The Lancet 392, 10159 (2018): 1684-1735. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31891-9. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Civil & Environmental Engineering at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Civil & Environmental Engineering Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Global Health Metrics Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 GBD 2017 Mortality Collaborators* Summary Lancet 2018; 392: 1684–735 Background Assessments of age-specific mortality and life expectancy have been done by the UN Population Division, This online publication has been Department of Economics and Social Affairs (UNPOP), the United States Census Bureau, WHO, and as part of corrected. The corrected version previous iterations of the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD). Previous iterations of first appeared at thelancet.com the GBD used population estimates from UNPOP, which were not derived in a way that was internally consistent on June 20, 2019 with the estimates of the numbers of deaths in the GBD. -

10. First Report and Recommendations

Interdisciplinary Committee for integration of Ayurveda and Yoga Interventions in the 'National Clinical Management Protocol: COVID-19' (OM No. A. 17020/1/2020-E.I dated 16th July 2020, Ministry of AYUSH, Govt. of India) FIRST REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS Index S.No. Contents Page Prologue iii Executive Summary 1-5 1 Background 6-14 2 Empirical evidence for Ayurveda and Yoga 14-28 3 Initiatives by Ministry of AYUSH for COVID-19 28-29 4 Interim trends of Ongoing studies on COVID-19 29-34 5 Rationale for positioning Ayurveda and Yoga interventions for 34-40 inclusion in Clinical management protocol: COVID-19 6 Recommendations 40-45 7 References 45-65 8 Annexures 1- 146 8.1 Annexure I - OM No. A. 17020/1/2020-E.I dated 16th July 2020, ` Ministry of AYUSH, Govt. of India 8.2 Annexure II – Minutes of 1st Meeting of Interdisciplinary Committee held on 24th July 2020 at 3.30 PM through Video Conference 8.3 Annexure III – Minutes of 2nd Meeting of Interdisciplinary Committee to be held on 5th August 2020 8.4 Annexure IV: Clinical management protocol: COVID-19, MoHFW, DGHS, GoI, Version 5; 03.07.20 8.5 Annexure V:Published scientific evidence on safety and usage of Ayurveda interventions in prophylaxis and treatment of COVID-19 (Experimental, Clinical studies) (AYUSH 64, Guduchi, Pippali and Ashwagandha) 8.6 Annexure VI: Pharmacopeial Standards and Quality parameters of Ayurveda interventions in prophylaxis and treatment of COVID-19 (AYUSH 64, Guduchi, Pippali and Ashwagandha) 8.7. Annexure VII: Guidelines for Ayurveda Practitioners for COVID-19 (Ministry of AYUSH, Govt. -

20130118104629Small41.Pdf

Crores of Indian households. A number of family members. Multiple needs. One choice. Joint promoters’ statement “A presence in every house, a recall in every mind – ‘ghar ghar mein Emami’ – has been our driving inspiration since inception” Joint promoters Shri R.S. Agarwal and Shri R.S. Goenka, highlight the Company’s direction and potential There are a number of numerical another year of our successful growth. Emami and growth parameters that one can use to Our performance improved While apparently it appears that 2007- demonstrate that we performed significantly as 2007-08 was a good 08 was tilted towards the industry, the creditably during the financial year year with our topline and bottomline fact remains that we confronted the 2007-08, but the one that stands the growing by 13% and 41% respectively. biggest challenges in terms of an test of industry, analysts and company We feel that there was a sustained unprecedented increase in the cost of is our performance compared with the growth in per capita income, riding on raw materials, a strong price- broad industry average. For instance, the ripple effect of India’s economic sensitivity across most product the broad FMCG industry in India grew growth which benefited a bigger categories, a greater need for wider at a CAGR of about 6% in the last concentration of households. As there and deeper distribution to reach three years; Emami grew at a CAGR was a perceptible increase in people’s customers and the ever-lingering of 25%. aspirations and purchasing power, our threat from counterfeit and This stellar performance sends multiple advertising and brand positioning unorganised products. -

Ministry of Home Affairs Telephone List ********

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS TELEPHONE LIST ******** HOME MINISTER’S OFFICE NAME & DESIGNATION Room No. OFFICE I.Com RESIDENCE/EMAIL 104 23092462 - - AMIT SHAH 23094686 HOME MINISTER 23017256 (PH) 23017580 (PH)(F) SAKET KUMAR 105 23092462 414 - PS TO HM 23094686 23094221(FAX) RAJEEV KUMAR 107 23092462 414 - OSD in HM Office 23094686 23092113(FAX) SATISH KUMAR CHHIKARA 23092462 414 - OSD in HM Office 23094686 23092979(FAX) ABHISHEK M. CHAUDHARI 103-A 23092462 414 - APS TO HM VIJAY KUMAR UPADHYAY 10-C 23093038 487 - DS (HMO) Dr. RAM MOHAN SHARMA R. No. 01 23075183 787 - Legal Advisor (HM Office) MDCNS 23072674(FAX) MINISTER OF STATE (N) OFFICE NITYANAND RAI 101 23092870 - - MINISTER OF STATE 23092595 SURESH KUMAR 198 23092595 270 - DIRECTOR 23094896(FAX) PS TO MoS(N) KUMAR KRANTI 196-A 23092870 270 - ADDL.PS TO MOS 23094896(FAX) ALOK KUMAR 117-B 23092595 270 - PPS O/o MoS MINISTER OF STATE(AM) OFFICE AJAY KUMAR MISHRA 127 23092073 - MINISTER OF STATE 23094054 ANANT KISHORE SARAN 127-B 23092073 318 [email protected] DIR O/o MoS (AM) 23094054 YOGESH SHARMA 125-B 23092073 318 [email protected] PSO O/o MoS (AM) 23094054 SHIV KUMAR 125-B 23092073 ̘318 US O/o MoS(AM) 23094495 23093549(FAX) AMIT JAIN 126-C 23092073 318 PS O/o MoS(AM) 23094054 23094495 23093549(FAX) RAJESH P. DALAL 126-C 23092073 318 SO O/o MoS(AM) 23094054 23093549(FAX) MINISTER OF STATE(NP) OFFICE NISITH PRAMANIK 127-A 23092123 - MINISTER OF STATE 23093143 MUKESH KUMAR 126-A 23092123 432 PPS 23093143 SANDEEP AMBASTHA 126-A 23092123 432 PS 23093143 HOME SECRETARY’S OFFICE AJAY KUMAR BHALLA 113 23092989 215 [email protected] HOME SECRETARY 23093031 23093003 (FAX) M JAGANNATHA RAO 113-A 23092989 254 [email protected] Sr. -

List of Officers Who Attended Courses at NCRB

List of officers who attened courses at NCRB Sr.No State/Organisation Name Rank YEAR 2000 SQL & RDBMS (INGRES) From 03/04/2000 to 20/04/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. GOPALAKRISHNAMURTHY SI 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri P. MURALI KRISHNA INSPECTOR 3 Assam Shri AMULYA KUMAR DEKA SI 4 Delhi Shri SANDEEP KUMAR ASI 5 Gujarat Shri KALPESH DHIRAJLAL BHATT PWSI 6 Gujarat Shri SHRIDHAR NATVARRAO THAKARE PWSI 7 Jammu & Kashmir Shri TAHIR AHMED SI 8 Jammu & Kashmir Shri VIJAY KUMAR SI 9 Maharashtra Shri ABHIMAN SARKAR HEAD CONSTABLE 10 Maharashtra Shri MODAK YASHWANT MOHANIRAJ INSPECTOR 11 Mizoram Shri C. LALCHHUANKIMA ASI 12 Mizoram Shri F. RAMNGHAKLIANA ASI 13 Mizoram Shri MS. LALNUNTHARI HMAR ASI 14 Mizoram Shri R. ROTLUANGA ASI 15 Punjab Shri GURDEV SINGH INSPECTOR 16 Punjab Shri SUKHCHAIN SINGH SI 17 Tamil Nadu Shri JERALD ALEXANDER SI 18 Tamil Nadu Shri S. CHARLES SI 19 Tamil Nadu Shri SMT. C. KALAVATHEY INSPECTOR 20 Uttar Pradesh Shri INDU BHUSHAN NAUTIYAL SI 21 Uttar Pradesh Shri OM PRAKASH ARYA INSPECTOR 22 West Bengal Shri PARTHA PRATIM GUHA ASI 23 West Bengal Shri PURNA CHANDRA DUTTA ASI PC OPERATION & OFFICE AUTOMATION From 01/05/2000 to 12/05/2000 1 Andhra Pradesh Shri LALSAHEB BANDANAPUDI DY.SP 2 Andhra Pradesh Shri V. RUDRA KUMAR DY.SP 3 Border Security Force Shri ASHOK ARJUN PATIL DY.COMDT. 4 Border Security Force Shri DANIEL ADHIKARI DY.COMDT. 5 Border Security Force Shri DR. VINAYA BHARATI CMO 6 CISF Shri JISHNU PRASANNA MUKHERJEE ASST.COMDT. 7 CISF Shri K.K. SHARMA ASST.COMDT. -

Alphabetical List of Persons for Whom Recommendations Were Received for Padma Awards - 2015

Alphabetical List of Persons for whom recommendations were received for Padma Awards - 2015 Sl. No. Name 1. Shri Aashish 2. Shri P. Abraham 3. Ms. Sonali Acharjee 4. Ms. Triveni Acharya 5. Guru Shashadhar Acharya 6. Shri Gautam Navnitlal Adhikari 7. Dr. Sunkara Venkata Adinarayana Rao 8. Shri Pankaj Advani 9. Shri Lal Krishna Advani 10. Dr. Devendra Kumar Agarwal 11. Shri Madan Mohan Agarwal 12. Dr. Nand Kishore Agarwal 13. Dr. Vinay Kumar Agarwal 14. Dr. Shekhar Agarwal 15. Dr. Sanjay Agarwala 16. Smt. Raj Kumari Aggarwal 17. Ms. Preety Aggarwal 18. Dr. S.P. Aggarwal 19. Dr. (Miss) Usha Aggarwal 20. Shri Vinod Aggarwal 21. Shri Jaikishan Aggarwal 22. Dr. Pratap Narayan Agrawal 23. Shri Badriprasad Agrawal 24. Dr. Sudhir Agrawal 25. Shri Vishnu Kumar Agrawal 26. Prof. (Dr.) Sujan Agrawal 27. Dr. Piyush C. Agrawal 28. Shri Subhash Chandra Agrawal 29. Dr. Sarojini Agrawal 30. Shri Sushiel Kumar Agrawal 31. Shri Anand Behari Agrawal 32. Dr. Varsha Agrawal 33. Dr. Ram Autar Agrawal 34. Shri Gopal Prahladrai Agrawal 35. Shri Anant Agrawal 36. Prof. Afroz Ahmad 37. Prof. Afzal Ahmad 38. Shri Habib Ahmed 39. Dr. Siddeek Ahmed Haji Panamtharayil 40. Dr. Ranjan Kumar Akhaury 41. Ms. Uzma Akhtar 42. Shri Eshan Akhtar 43. Shri Vishnu Akulwar 44. Shri Bruce Alberts 45. Captain Abbas Ali 46. Dr. Mohammed Ali 47. Dr. Govardhan Aliseri 48. Dr. Umar Alisha 49. Dr. M. Mohan Alva 50. Shri Mohammed Amar 51. Shri Gangai Amaren 52. Smt. Sindhutai Ramchandra Ambike 53. Mata Amritanandamayi 54. Dr. Manjula Anagani 55. Shri Anil Kumar Anand 56. -

University of Hyderabad

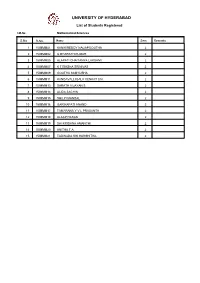

UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 15IMMM01 KANIKIREDDY NAGAPOOJITHA 2 2 15IMMM02 G BHARATH KUMAR 2 3 15IMMM05 ALAPATI CHAITANYA LAKSHMI 2 4 15IMMM07 K TITIKSHA SRINIVAS 2 5 15IMMM09 GOUTHA SAMYUSHA 2 6 15IMMM11 KANDAVALLI BALA VENKAT SAI 2 7 15IMMM13 SARATH VIJAYAN S 2 8 15IMMM14 ALIDA SACHIN 2 9 15IMMM15 SHILPI MANDAL 2 10 15IMMM16 GARIKAPATI ANAND 2 11 15IMMM17 TAMARANA Y V L PRASANTH 2 12 15IMMM18 ALAAP HASAN 2 13 15IMMM19 SAI KRISHNA AMANCHI 2 14 15IMMM20 ANITHA.T.A 2 15 15IMMM21 TADINADA SRI HARSHITHA 2 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 14IMMM01 P R NANDA KUMARI 4 2 14IMMM03 RUDDARRAJU AMRUTHA 4 3 14IMMM04 SAMANAPALLI SRICHANDRA 4 4 14IMMM08 MADISHETTI SAIKIRAN 4 5 14IMMM13 BODA SWAROOPA 4 6 14IMMM14 TAPONITYA SAMANTARAY 4 7 14IMMM16 SAPPIDI SANJAY 4 8 14IMMM17 PINJARI HUSSAIN PEERA 4 9 14IMMM19 KAUSTUB MALLAPRAGADA 4 10 14IMMM20 PUJARI MANISH MADHAV 4 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 12IMMM16 KORUTLA ROHITHKUMAR 6 2 13ICMC20 REBALLI PRIYANKA 6 3 13IMMM01 EESHAN HASAN 6 4 13IMMM05 AKINEPALLY PRATIMA RAO 6 5 13IMMM06 SILADITYA BASU 6 6 13IPMP18 S V SRIHARSHA 6 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. Mathematical Sciences S.No R.No. Name Sem Remarks 1 11IMMM17 DEEPAK PAWAR 8 2 12ILMB24 BASAVANAGA AVINASH KUMAR 8 3 12IMMM06 KODIMYALA SHARANYA 8 4 12IMMM07 NAMRATA ARVIND 8 5 12IMMM08 SUBHAS CHANDRA KOLLI 8 6 12IMMM10 AMEYA PHADKE 8 7 12IMMM11 ATTAL SURYA 8 8 12IMMM13 A RAMADEVI 8 9 12IMMM21 KOPPULA BALARAJU 8 UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD List of Students Registered I.M.Sc. -

List of Total Books T.S.Chanakya

LIST OF BOOKS (T.S.CHANAKYA) Sr. No. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR 1 SOCIAL STUDIES VINCENT G HUTCHINSON 2 2001 A SPACE ODYSSEY ARTHUR CLARKE 3 A HISTORY OF INDIA - VOL -1 ROMILA THAPAR 4 TRANISISTOR AMPLIPHIERS FOR AUDIO FRIQUENCIES THOMAS RUDDEN 5 THE BOOK OF FLAGS 5th REVED CAMPELL & EVANS 6 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -1 PUBLICATION DIVISION 7 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -2 PUBLICATION DIVISION 8 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -3 PUBLICATION DIVISION 9 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -4 PUBLICATION DIVISION 10 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -5 PUBLICATION DIVISION 11 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -6 6 PUBLICATION DIVISION 12 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -7 PUBLICATION DIVISION 13 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -8 PUBLICATION DIVISION 14 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -9 PUBLICATION DIVISION 15 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -10 PUBLICATION DIVISION 16 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -11 PUBLICATION DIVISION 17 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -12 PUBLICATION DIVISION 18 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -13 PUBLICATION DIVISION 19 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -14 PUBLICATION DIVISION 20 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -15 PUBLICATION DIVISION 21 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL - 16 PUBLICATION DIVISION 22 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -17 PUBLICATION DIVISION 23 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - VOL -18 PUBLICATION DIVISION 24 COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATHMA GANDHI - -

List of Names Drawing Central Samman Pension Sl No

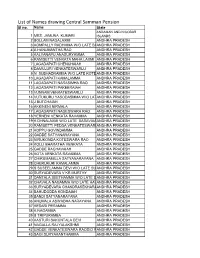

List of Names drawing Central Samman Pension Sl no. Name State ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 MRS. JAMUNA KUMARI ISLANDS 2 BOLLAM NAGALAXMI ANDHRA PRADESH 3 KOMPALLY RADHMMA W/O LATE BAANDHRA PRADESH 4 A HANUMANTHA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 5 KALYANAPU ANASURYAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 6 RAMISETTI VENKATA MAHA LAXMI ANDHRA PRADESH 7 LAGADAPATI CHENCHAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 8 DAMULURI VENKATESWARLU ANDHRA PRADESH 9 N SUBHADRAMMA W/O LATE KOTEANDHRA PRADESH 10 LAGADAPATI KAMALAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 11 LAGADAPATI NARASIMHA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 12 LAGADAPATI PAKEERAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 13 VUNNAM VENKATESWARLU ANDHRA PRADESH 14 VUTUKURU YASODASMMA W/O LATANDHRA PRADESH 15 J BUTCHAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 16 AKKINENI NIRMALA ANDHRA PRADESH 17 LAGADAPATI NAGESWARA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 18 YERNENI VENKATA RAVAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 19 K DHNALAXMI W/O LATE BASAVAIAANDHRA PRADESH 20 RAMISETTI PEDDA VENKATESWARLANDHRA PRADESH 21 KOPPU GOVINDAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 22 GADDE SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 23 NIRUKONDA KOTESWARA RAO ANDHRA PRADESH 24 KOLLI BHARATHA VENKATA ANDHRA PRADESH 25 GADDE RAGHAVAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 26 KOTA VENKATA RAVAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 27 CHIRUMAMILLA SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 28 CHERUKURI KAMALAMMA ANDHRA PRADESH 29 S SUSEELAMMA DEVI W/O LATE SU ANDHRA PRADESH 30 SURYADEVARA V KR MURTHY ANDHRA PRADESH 31 DANTALA SEETHAMMA W/O LATE DANDHRA PRADESH 32 CHAVALA NAGAMMA W/O LATE HAVANDHRA PRADESH 33 SURYADEVARA CHANDRASEKHARAANDHRA PRADESH 34 BAHUDODDA KONDAIAH ANDHRA PRADESH 35 BANDI SATYANARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 36 ANUMALA ASWADHA NARAYANA ANDHRA PRADESH 37 KESARI PERAMMA ANDHRA -

Emami… a Bullish

www.emamiltd.in | VOLUME: XXXIII Making people healthy and beautiful, naturally 2015-2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 Corporate Information Chairman Directors R.S. Agarwal R.S. Goenka K.N. Memani Managing Director Y.P. Trivedi Sushil K. Goenka M.D. Mallya Rama Bijapurkar CEO-Finance, Strategy & P.K. Khaitan Business Development and CFO Sajjan Bhajanka N.H. Bhansali S.B. Ganguly Amit Kiran Deb Company Secretary & VP-Legal Mohan Goenka A.K. Joshi Aditya V. Agarwal Harsha V. Agarwal Auditors Priti A Sureka S.K. Agrawal & Co Prashant Goenka Chartered Accountants BOARD COMMITTEES Audit Committee Finance Committee S.B. Ganguly, Chairman R.S. Goenka, Chairman R.S. Goenka Sushil K. Goenka Mohan Goenka Sajjan Bhajanka Aditya V. Agarwal Amit Kiran Deb Harsha V. Agarwal Nomination and Remuneration Committee Priti A Sureka Amit Kiran Deb, Chairman Risk Management Committee Sajjan Bhajanka R.S. Goenka, Chairman S.B. Ganguly S.B. Ganguly Sushil K. Goenka Share Transfer Committee Mohan Goenka Mohan Goenka, Chairman Harsha V. Agarwal Aditya V. Agarwal Priti A Sureka Harsha V. Agarwal Priti A Sureka Corporate Governance Committee S.B. Ganguly, Chairman Stakeholders’ Relationship Committee R.S. Goenka Sajjan Bhajanka, Chairman Y.P. Trivedi Amit Kiran Deb S.B. Ganguly Mohan Goenka Corporate Social Responsibility Committee Harsha V. Agarwal Sushil K. Goenka, Chairman Amit Kiran Deb Mohan Goenka Harsha V. Agarwal Priti A Sureka OUR PRESENCE 60+ COUNTRIES | 7 FACTORIES | 1 OVERSEAS UNIT | 4 REGIONAL OFFICES | 33 DEPOTS | 8 OVERSEAS SUBSIDIARIES. BANKERS CANARA BANK | ICICI BANK LTD. | CITI BANK N.A. | HDFC BANK LTD | HSBC LTD | DBS BANK LTD.