Henotypic and Behavioral Variability Within Angelman Syndrome Group with UPD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aalseth Aaron Aarup Aasen Aasheim Abair Abanatha Abandschon Abarca Abarr Abate Abba Abbas Abbate Abbe Abbett Abbey Abbott Abbs

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 35 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 306 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 98.500 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

On Time to Therapy Initiation and Resection Margins: a Retrospective Analysis of 104 Immediate Jaw Reconstructions

cancers Article Impact of Planning Method (Conventional versus Virtual) on Time to Therapy Initiation and Resection Margins: A Retrospective Analysis of 104 Immediate Jaw Reconstructions Michael Knitschke * , Christina Bäcker, Daniel Schmermund, Sebastian Böttger , Philipp Streckbein , Hans-Peter Howaldt and Sameh Attia Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Justus-Liebig-University, Klinikstrasse 33, 35392 Giessen, Germany; [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (D.S.); [email protected] (S.B.); [email protected] (P.S.); [email protected] (H.-P.H.); [email protected] (S.A.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Computer-aided design and manufacturing of osseous reconstructions are cur- rently widely used in jaw reconstructive surgery, providing an improved surgical outcome and decreased procedural stumbling block. However, data on the influence of planning time on the time-to-surgery initiation and resection margin are missing in the literature. This retrospective, monocentric study compares process times from the first patient contact in hospital, time of in-house Citation: Knitschke, M.; Bäcker, C.; or out-of-house biopsy for tumor diagnosis and surgical therapy of tumor resection, and immediate Schmermund, D.; Böttger, S.; reconstruction of the jaw with free fibula flaps (FFF). Two techniques for reconstruction are used: Streckbein, P.; Howaldt, H.-P.; Attia, S. Virtual surgical planning (VSP) and non-VSP. A total of 104 patients who underwent FFF surgery for Impact of Planning Method immediate jaw reconstruction from 2002 to 2020 are included. The study findings fill the gaps in the (Conventional versus Virtual) on literature and obtain clear insights based on the investigated study subjects. -

CLOC to Launch in Europe the Growing Pains Of

aka ‘The Orange Rag’ Top stories in this issue… Ben Gardner leaves Links for Wavelength p.2 iManage benefits from Elite Envision end of life p.7 Insider launches legal tech startup initiative p.10 All the latest wins & deals p.12 Under the hood: Baker McKenzie’s innovation programme p.14 CLOC to launch in The growth of the organisation mirrors the growth in the legal operations role: in a 2016 survey by the Association Europe of Corporate Counsel, it emerged that 48% of legal teams now have legal operations staff – double the figure in 2015. In what could turn out to be one of the most significant events It was in San Francisco on 2-4 May last year that this year for European legal technology vendors attempting CLOC ran its first ‘Institute’ – a conference that it plans to to expand their presence within the corporate legal sector, repeat in the UK. Writing about the Institute in a Riverview Corporate Legal Operations Consortium – better known to Law blog, Riverview’s CEO Karl Chapman said: “And now the market as CLOC - will launch in Europe at the end of we have CLOC. An organisation that, with momentum February, led by VMware’s vice president & deputy general and great timing, helps facilitate and stimulate eco-system counsel for worldwide legal operations, Áine Lyons. change. When people look back in 10-15 years I suspect The influential US organisation, which is driving that 2-4 May 2016 will be seen as one of the key milestones change in the world of corporate legal operations and has in the transition of the legal market. -

THESIS for DOCTORAL DEGREE (Ph.D.) at Karolinska Institutet, Publicly Defended in Månen, Alfred Nobel Allé 8, 9Q, Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge, On

From DEPARTMENT OF BIOSCIENCES AND NUTRITION Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden REGULATION AND FUNCTION OF CILIARY DYSLEXIA CANDIDATE GENES Andrea Bieder Stockholm 2018 Front cover image shows cilia of renal epithelial cells in human kidney tubuli, visualized with anti-acetylated α-tubulin (red) and anti-DCDC2 (green) antibodies. Cellular nuclei are shown in blue. Reprinted from The American Journal of Human Genetics, Vol. 96/1, Schueler et al., DCDC2 Mutations Cause a Renal-Hepatic Ciliopathy by Disrupting Wnt Signaling p. 81-92. Reproduced with permission from The American Society of Human Genetics, Copyright 2015 All previously published papers were reproduced with permission from the publisher. Published by Karolinska Institutet. Printed by E-print AB 2018 © Andrea Bieder, 2018 ISBN 978-91-7831-151-4 Regulation and function of ciliary dyslexia candidate genes THESIS FOR DOCTORAL DEGREE (Ph.D.) at Karolinska Institutet, publicly defended in Månen, Alfred Nobel Allé 8, 9Q, Karolinska Institutet, Huddinge, on Friday, 12th of October 2018, 9.30 am By Andrea Bieder, MSc Principal Supervisor: Opponent: Dr. Isabel Tapia-Páez Prof. Lotte Pedersen Karolinska Institutet University of Copenhagen Department of Medicine, Solna Department of Biology Co-supervisors: Examination Board: Prof. Juha Kere Prof. Marie-Louise Bondeson Karolinska Institutet Uppsala University Department of Biosciences and Nutrition Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology Dr. Hans Matsson Karolinska Institutet Prof. Mattias Alenius Department of Women’s and Children’s Health Umeå University Department of Molecular Biology Dr. Anna Falk Karolinska Institutet Prof. Maria Eriksson Department of Neuroscience Karolinska Institutet Department of Biosciences and Nutrition To my parents Elisabeth & Markus “This inability is so remarkable, and so pronounced, that I have no doubt it is due to some congenital defect” W. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Novel Retinoid Enhancers for Anti- Cancer Therapies

NOVEL RETINOID ENHANCERS FOR ANTI- CANCER THERAPIES A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Christopher R Gardner Supervisors: Prof. Naresh Kumar Dr. Belamy Cheung Prof. David StC. Black School of Chemistry The University of New South Wales Kensington, Australia July, 2015 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Gardner First name: Christopher Other namefs: Robert Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: PhD School: Chemistry Faculty: Science Title: Novel retinoid enhancers for anti-cancer therapies Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Retinoids play a crucial role in the treatment of multiple human cancers, particularly neuroblastoma and leukaemia. However, their utility is often hampered by the inherent toxicities associated with the concentrations necessary for therapeutic benefit, as well as innate or acquired resistance to treatment. This thesis focuses on the discovery and development of novel scaffolds that possess cytotoxic activity mediated through the retinoid pathways. A protocol for docking scaffolds into the binding site of the retinoic acid receptor ~ (RAR~) was developed. These docking methodologies were used to identify novel scaffolds as potential RAR~ ligands, as well as probe the mechanisms behind the observed structure activity relationships (SAR) of the prepared compounds. A wide range of novel indole-benzothiazole acetamides were synthesized via PyBOP amide coupling of 3-indoleacetic acids and 2-aminobenzothiazoles. These scaffolds were investigated for their cytotoxic activity against neuroblastoma cells. Several analogues were found to have low micromolar IC50 values, demonstrated selectivity towards cells with high RAR~ expression and also were selective for cancerous cells over normal cells. -

Guanine Phosphoribosyltransferase of Helicobacter Pylori As a Potential Therapeutic Target

CHARACTERISATION OF THE XANTHINE- GUANINE PHOSPHORIBOSYLTRANSFERASE OF HELICOBACTER PYLORI AS A POTENTIAL THERAPEUTIC TARGET Megan Jane Duckworth A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, The University of New South Wales 2008 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: DUCKWORTH First name: MEGAN Other name/s:JANE Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: 1780 School: MEDICAL SCIENCES (PATHOLOGY) Faculty: MEDICINE Title: CHARACTERISATION OF THE XANTHINE-GUANINE PHOSPHORIBOSYLTRANSFERASE OFHELICOBACTER PYLORI AS A POTENTIAL THERAPEUTIC TARGET Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Helicobacter pylori infects more than half of the global population and causes gastric disorders. The increasing development of antibiotic resistance by the bacterium continues to limit treatment options. The identification and characterisation of novel therapeutic targets are necessary for successful future treatment of the infection. One potential target for therapeutic intervention is the gpt gene encoded by hp0735 (jhp0672) in H. pylori strain 26695 (J99). This gene produces a putative xanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (XGPRTase), an enzyme of the purine salvage synthesis pathway. This project employed theoretical, molecular and biochemical approaches to investigate features of H. pylori gpt and XGPRTase that will serve to ascertain their therapeutic potential. The production of a functional XGPRTase by H. pylori was investigated in cell-free extracts, and the kinetic parameters of this activity were compared to those of purified rXGPRTase enzyme. The three 6-oxopurine substrates were recognised by rXGPRTase and allosteric kinetics were observed for some substrates of the enzyme in cell-free extracts and for purified enzyme. -

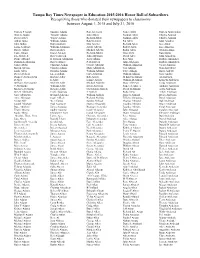

Tampa Bay Times Newspaper in Education 2015-2016 Honor Roll of Subscribers Recognizing Those Who Donated Their Newspapers To

Tampa Bay Times Newspaper in Education 2015-2016 Honor Roll of Subscribers Recognizing those who donated their newspapers to classrooms between August 1, 2015 and July 31, 2016 Patricia P Aaron Susanne Adams Ron Alberssen Nancy Allen Patricia Ammendola Warren Abadie Timothy Adams John Albert Norman Allen Charles Ammon David Abbey Wayne Adams Richard Albert Norman Allen Charles Ammon Arthur Abbo William Adams Robert Albert Pat Allen John Amodeo John Abbott Ruth Adamski Don Alberta Richard Allen Jack Amor Louis A Abbott William Adamson Albert Alberts Robert Allen Lisa Amoruso Robert Abbott Robi Adaskes Michael Alberts Robin Allen William Amos Tony Abbott Eloise Adcock Richard Alberts Tina Allen Ron Amritt E L Abbott Jr Robert Adcock John Albertson David Alley John Amsallem Diane Abboud H Truman Addington Josep Albino Ray Allia Barbara Amspoker Dominick Abbriano Robert Adikes P H Albrecht John Allickson Barbara Amundsen James Abeln Christine Adkins George Albright William Allington Victor Amurgis Martin Abelon Claudia Adkins Mary Albrighton Gail Allison Stan Anderberg Linda Abels Douglas Adkins William Albring Terry Allison Holly Anderle David Abelson Lucas Adlam Gary Albritton William Allison Gary Anders Diana C Abendschein Barbara Adler Bob Albury M Kristen Allman Al Andersen D Aber E Adler Lonnie Albury William D Allman Kenneth Andersen William Abercrombie Michele Adler Michael Alderfer Mary Allmeyer Linda Andersen C Abernathy William Adler Helen Alderson Nancy A Allocca Anthony Anderson Michael Abernathy Howard Adlin Gwendolyn Aldrich -

Human Genetics and Clinical Aspects of Neurodevelopmental Disorders

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/000687; this version posted October 6, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Human genetics and clinical aspects of neurodevelopmental disorders Gholson J. Lyon1,2,3,*, Jason O’Rawe1,3 1Stanley Institute for Cognitive Genomics, One Bungtown Road, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, NY, USA, 11724 2Institute for Genomic Medicine, Utah Foundation for Biomedical Research, E 3300 S, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 84106 3Stony Brook University, 100 Nicolls Rd, Stony Brook, NY, USA, 11794 * Corresponding author: Gholson J. Lyon Email: [email protected] Other author emails: Jason O'Rawe: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/000687; this version posted October 6, 2014. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Introduction “our incomplete studies do not permit actual classification; but it is better to leave things by themselves rather than to force them into classes which have their foundation only on paper” – Edouard Seguin (Seguin, 1866) “The fundamental mistake which vitiates all work based upon Mendel’s method is the neglect of ancestry, and the attempt to regard the whole effect upon off- spring, produced by a particular parent, as due to the existence in the parent of particular structural characters; while the contradictory results obtained by those who have observed the offspring of parents apparently identical in cer- tain characters show clearly enough that not only the parents themselves, but their race, that is their ancestry, must be taken into account before the result of pairing them can be predicted” – Walter Frank Raphael Weldon (Weldon, 1902). -

Reflections 2018

St. Augustine Church FALL 2018 VOLUME 32 ISSUE 1 REFLECTIONS PASTOR’S GREETING Dear Parishioners, Sunday, June 3, was a day in the life of the parish of St. Augustine, an historic day. It was the day we celebrated the 125th Anniversary of the beginning of our parish in 1892. Most Reverend John Barres, Bishop of Rockville Centre and a native son of our parish, joined us both at the Anniversary Mass and at the festive Parish Picnic that followed. June 3rd just happened to be the 90th Anniversary of the dedication of our English Country Gothic Style Church by Patrick Cardinal Hayes in 1928. June 3rd was also a day to celebrate our successful 125th Anniversary Campaign. A remarkable number of parish families and households joined together to support a campaign to provide for the future of St. Augustine Parish. Contributions and pledges were received at all levels, from under $100 to over $100,000 and from young families as well as our seniors, a true representation of our increasingly diverse community. We exceeded our $2,000,000 pledge goal by more than $173,000 from approximately 280 families. (See page 10-11 for a complete list of donors.) Parish support has enabled us to install a new lighting system in the church and to paint the interi- or walls of the church in the last two years. During the month of June, the St. John the Evangelist Window has been restored. We are working to provide a new handicap accessible restroom off the vestibule of the church. Both pastor and parish owe a special note of recognition and appreciation to our Campaign Committee! The committee was co-chaired by Linnea Holmes, Mark McNally, and Mary Jo Mitchell and assisted by current and former Trustees Rob Gittings, Sally Robling, Carla Porter and Greg Ran- dolph, and parishioners Rita Murray, Shannon Pujadas and John Spollen. -

1948 Obituaries in the Canton Repository

Index to 1948 Obituaries in the Canton Repository Published by the Stark County District Library, 2005 Canton, OH Page 1 Index to 1948 Obituaries in the Canton Repository The following is an alphabetical listing, by the deceased’s surname, of obituaries that appeared in the Canton, Ohio newspaper, The Repository. It was compiled by the library staff during the course of the year in the hope that it would be a useful tool to genealogy, as well as other researchers. To use this index, simply locate the name of the person whose obituary you wish to find. The entries will appear as follows: Miller William A. (Estella M.) Mrs. 1940 Jan. 13 30 The first column is the name of the deceased. The second gives the date on which the item appeared. And the third tells the page number containing the obituary. You may find one name with multiple listings showing different dates and locations in the paper. This indicates consecutive listings for that individual. I encourage you to view each for additional information. Page 2 Surname Given Name Maiden Title Year Mon. Day Pg Abbott Charles A. (Gertrude I.) Mrs. 1948 June 15 14 Abdi Xamal 1948 Oct. 8 34 Abee Theodore (Edna M.) Mrs. 1948 Oct. 24 56 Abel Harry S. 1948 Jan. 17 2 Abel infant (William Ralph) 1948 May 30 17 Abrams James 1948 Dec. 29 9 Abt Oscar M. 1948 Nov. 2 1 Abt Oscar M. 1948 Nov. 3 15 Achemire William B. 1948 June 4 27 Acker O. W. 1948 Dec. 27 9 Acker O. -

Esentio Sues HBR Consulting Over

aka ‘The Orange Rag’ Top stories in this issue… RBRO says it’s BAU in the UK after departures p.2 Akin Gump appoints Aaron Ruleman as CIO p.4 Workshare throws down the gauntlet p.4 New Startup Directory p.6 Wins and deals p.25 Buyer’s Guide to eDisclosure out now! p.27 Date for your diary: NextUp & ILTA social p.27 eSentio sues HBR eSentio claims that having joined HBR to work in NetDocuments conversions for law firms: “Mukerji was Consulting over Net- instrumental in HBR’s recent wins of NetDocuments conversion projects with Akin and King & Spalding.” Documents swapout ESENTIO SUES HBR CONSULTING OVER NETDOCUMENTS The iManage to NetDocuments swapout by Akin Gump Strauss CONTINUES ON P.2 Hauer & Feld and King & Spalding has formed the basis of a US lawsuit against HBR Consulting by eSentio Technologies. eSentio seeks millions of dollars in compensation, alleging Exclusive: Thought- that a former employee breached his restrictive covenants in winning the NetDocuments conversion work for HBR. River raises over $1m eSentio, a Washington-based technology consulting company, on 10 April filed a lawsuit against former employee Contract risk analysis platform ThoughtRiver has raised over $1m Rajiv Mukerji and his new employee HBR Consulting, alleging in funding, Legal IT Insider can reveal, including investment that Mukerji breached a restrictive covenant by interfering with from former Vodafone UK CEO Guy Laurence and former co- eSentio’s relationships with Akin Gump and King & Spalding. head of Investment Banking and corporate broking, UK and In its claim, eSentio says that it is recognised as the Ireland at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Michael Findlay.