Central Stoneroller Campostoma Anomalum Michauxi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES Tables STEPHEN T. ROSS University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London © 2013 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN 978-0-520-24945-5 uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 1 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 2 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 1.1 Families Composing 95% of North American Freshwater Fish Species Ranked by the Number of Native Species Number Cumulative Family of species percent Cyprinidae 297 28 Percidae 186 45 Catostomidae 71 51 Poeciliidae 69 58 Ictaluridae 46 62 Goodeidae 45 66 Atherinopsidae 39 70 Salmonidae 38 74 Cyprinodontidae 35 77 Fundulidae 34 80 Centrarchidae 31 83 Cottidae 30 86 Petromyzontidae 21 88 Cichlidae 16 89 Clupeidae 10 90 Eleotridae 10 91 Acipenseridae 8 92 Osmeridae 6 92 Elassomatidae 6 93 Gobiidae 6 93 Amblyopsidae 6 94 Pimelodidae 6 94 Gasterosteidae 5 95 source: Compiled primarily from Mayden (1992), Nelson et al. (2004), and Miller and Norris (2005). uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 3 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 3.1 Biogeographic Relationships of Species from a Sample of Fishes from the Ouachita River, Arkansas, at the Confl uence with the Little Missouri River (Ross, pers. observ.) Origin/ Pre- Pleistocene Taxa distribution Source Highland Stoneroller, Campostoma spadiceum 2 Mayden 1987a; Blum et al. 2008; Cashner et al. 2010 Blacktail Shiner, Cyprinella venusta 3 Mayden 1987a Steelcolor Shiner, Cyprinella whipplei 1 Mayden 1987a Redfi n Shiner, Lythrurus umbratilis 4 Mayden 1987a Bigeye Shiner, Notropis boops 1 Wiley and Mayden 1985; Mayden 1987a Bullhead Minnow, Pimephales vigilax 4 Mayden 1987a Mountain Madtom, Noturus eleutherus 2a Mayden 1985, 1987a Creole Darter, Etheostoma collettei 2a Mayden 1985 Orangebelly Darter, Etheostoma radiosum 2a Page 1983; Mayden 1985, 1987a Speckled Darter, Etheostoma stigmaeum 3 Page 1983; Simon 1997 Redspot Darter, Etheostoma artesiae 3 Mayden 1985; Piller et al. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Reproductive Timing of the Largescale Stoneroller, Campostoma Oligolepis, in the Flint River, Alabama

REPRODUCTIVE TIMING OF THE LARGESCALE STONEROLLER, CAMPOSTOMA OLIGOLEPIS, IN THE FLINT RIVER, ALABAMA by DANA M. TIMMS A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Biological Sciences to The School of Graduate Studies of The University of Alabama in Huntsville HUNTSVILLE, ALABAMA 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor Dr. Bruce Stallsmith for all his guidance on this project and greater dedication to raising awareness to Alabama’s river ecosystems. I am grateful to my other committee members, Dr. Gordon MacGregor and Dr. Debra Moriarity also from UAH. Thanks to everyone who braved the weather and elements on collecting trips: Tiffany Bell, Austin Riley, Chelsie Smith, and Joshua Mann. I would like to thank Megan McEown, Corinne Peacher, and Bonnie Ferguson for dedicating long hours in the lab. Special thanks to Matthew Moore who assisted in collections, lab work, and data processing. Most of all, I would like to thank my husband, Patrick, for his love and encouragement in all my endeavors. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page • List of Figures viii • List of Tables x • CHAPTER ONE: Introduction 1 o Context 1 o Campostoma oligolepis Taxonomy 3 o History of Campostoma oligolepis 4 ▪ Campostoma oligolepis in the South 6 ▪ Campostoma Hybridization 8 ▪ Campostoma Ranges and Species Differentiation 9 ▪ Life History 12 ▪ Reproduction 12 o Purpose and Hypothesis 15 • CHAPTER TWO: Methodology 17 o Laboratory Analysis 19 o Reproductive Data 21 o Ovary and Oocyte Staging 22 o Statistical Analysis 22 • CHAPTER THREE: Results 27 o Reproductive Data 29 ▪ Ovary and Oocyte Development 32 ▪ Testicular Development 39 vi • CHAPTER FOUR: Discussion 40 o Study Limitations 40 o Lateral Line Scale Count 41 o Reproductive Cues and Environmental Influences 42 o Multiple-spawners 42 o Asymmetry of Ovaries 42 o Bourgeois Males 43 o Campostoma variability 44 o Conclusion 45 • WORKS CITED 46 vii LIST OF FIGURES Page • 1.1 Campostoma oligolepis, Largescale Stoneroller, specimens from the Flint River, Alabama. -

Population Characteristics of Central Stonerollers in Iowa Streams

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The Prairie Naturalist Great Plains Natural Science Society 12-2010 Population Characteristics of Central Stonerollers in Iowa Streams Scott M. Bisping Jesse R. Fischer Michael C. Quist Andrew J. Schaefer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tpn Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Botany Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Systems Biology Commons, and the Weed Science Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Natural Science Society at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Prairie Naturalist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Prairie Naturalist 42(3/4):109-115; 2010 Population Characteristics of Central Stonerollers in Iowa Streams SCOTT M. BISPING, JESSE R. FISCHER!, MICHAEL C. QUIST, AND ANDREW 1. SCHAEFER Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management, Iowa State University, Ames, IA USA, 50011 ABSTRACT The central stoneroller (Campostoma anomalum) is a herbivore that can have substantial effects on algal communities, nutrient dynamics, and energy flow in streams. Despite its importance in lotic ecosystems, little is known about its population dynamics in streams of the Great Plains. Our objective was to describe age structure, age-specific mortality, and growth rates of central stonerollers in three Iowa streams. We sampled fish from 41 reaches during June-August 2007. We sampled 466 central stonerollers, of which we aged 192. Fish varied in length from 32 to 130 mm and in age from age 0 to 4 years. -

![Kyfishid[1].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2624/kyfishid-1-pdf-1462624.webp)

Kyfishid[1].Pdf

Kentucky Fishes Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission To conserve, protect and enhance Kentucky’s fish and wildlife resources and provide outstanding opportunities for hunting, fishing, trapping, boating, shooting sports, wildlife viewing, and related activities. Federal Aid Project funded by your purchase of fishing equipment and motor boat fuels Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources #1 Sportsman’s Lane, Frankfort, KY 40601 1-800-858-1549 • fw.ky.gov Kentucky Fish & Wildlife’s Mission Kentucky Fishes by Matthew R. Thomas Fisheries Program Coordinator 2011 (Third edition, 2021) Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources Division of Fisheries Cover paintings by Rick Hill • Publication design by Adrienne Yancy Preface entucky is home to a total of 245 native fish species with an additional 24 that have been introduced either intentionally (i.e., for sport) or accidentally. Within Kthe United States, Kentucky’s native freshwater fish diversity is exceeded only by Alabama and Tennessee. This high diversity of native fishes corresponds to an abun- dance of water bodies and wide variety of aquatic habitats across the state – from swift upland streams to large sluggish rivers, oxbow lakes, and wetlands. Approximately 25 species are most frequently caught by anglers either for sport or food. Many of these species occur in streams and rivers statewide, while several are routinely stocked in public and private water bodies across the state, especially ponds and reservoirs. The largest proportion of Kentucky’s fish fauna (80%) includes darters, minnows, suckers, madtoms, smaller sunfishes, and other groups (e.g., lam- preys) that are rarely seen by most people. -

ABSTRACT Nutrient Enrichment Effects on Stream Periphyton

ABSTRACT Nutrient Enrichment Effects on Stream Periphyton Stoichiometry, Algal and Fish Assemblage Structure, and Grazing Fish-Periphyton Interactions Jason M. Taylor, Ph.D. Committee Chairperson: Ryan S. King, Ph.D. Anthropogenic inputs of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) create novel environmental conditions that alter biological organization and ecosystem functioning in freshwaters. My research objectives were: 1) identify levels of nutrient enrichment thresholds for stream periphyton nutrient ratios, individual algal and fish species abundances, and overall assemblage composition; 2) experimentally investigate interactions between P enrichment, an important grazing fish, and periphyton biomass and elemental composition; and 3) examine the influence of nitrogen enrichment on fish- mediated nutrient recycling effects on downstream ecosystem structure and function. Analyses of field collected data indicated that sharp declines in periphyton elemental composition, a synchronous decline in several algal species, and sharp declines in at least two benthic specialist fishes (Etheostoma spectabile and Campostoma anomalum) occurred when surface-water TP exceeded approximately 20 µg L-1 and when TN was greater than 550 µg L-1. A stream mesocosm experiment demonstrated that grazing by C. amomalum decreased benthic C:Chlorophyll a ratios, disrupted the continuous deposition of detritus and inorganic sediment, and as a result, increased periphyton P and N content. Variation in grazer effects on periphyton C:P and C:N ratios across the P enrichment treatments resulted in N:P ratios that were greater on grazed substrates in control and low P streams but grazer effects diminished with increasing P enrichment. A second experiment that measured nutrient recycling effects showed that fish-mediated nutrient recycling decreased periphyton C:N and increased C:P and N:P longitudinally in N enriched streams. -

The Blackside Dace (Chrosomus Cumberlandensis) and the Cumberland Arrow Darter (Etheostoma Sagitta) in Northeast Tennessee

WATER QUALITY’S INFLUENCE ON THE OCCUPANCY OF TWO JEOPARDIZED FISHES: THE BLACKSIDE DACE (CHROSOMUS CUMBERLANDENSIS) AND THE CUMBERLAND ARROW DARTER (ETHEOSTOMA SAGITTA) IN NORTHEAST TENNESSEE __________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the College of Science Morehead State University _________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science _________________________ by Brandon L. Yates July 5, 2017 ProQuest Number:10605069 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10605069 Published by ProQuest LLC ( 2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 Accepted by the faculty of the College of Science, Morehead State University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree. ______________________________ David J. Eisenhour Director of Thesis Master’s Committee: ________________________________, Chair David J. Eisenhour _________________________________ Brian C. Reeder _________________________________ David P. Smith _________________________________ Michael C. Compton ________________________ Date WATER QUALITY’S INFLUENCE ON THE OCCUPANCY OF TWO JEOPARDIZED FISHES: THE BLACKSIDE DACE (CHROSOMUS CUMBERLANDENSIS) AND THE CUMBERLAND ARROW DARTER (ETHEOSTOMA SAGITTA) IN NORTHEAST TENNESSEE Brandon L. Yates Morehead State University, 2017 Director of Thesis: __________________________________________________ David J. -

Aquatic Species Mapping in North Carolina Using Maxent

Aquatic Species Mapping in North Carolina Using Maxent Mark Endries U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Ecological Services Field Office, Asheville North Carolina INTRODUCTION The mission of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is to work with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, and plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. The Service is the lead governmental agency involved in the recovery of federally endangered and threatened species in freshwater and terrestrial habitats. To meet its recovery and protection goals, the Service: (1) works with other federal agencies to minimize or eliminate impacts to fish, wildlife, and plants from projects they authorize, fund, or carry out; (2) supports the improvement of fish and wildlife habitat on private land through technical and financial assistance; and (3) provides scientific knowledge and analyses to help guide the conservation, development, and management of the Nation’s fish and wildlife resources. Freshwater ecosystems present unique management challenges due to their linear spatial orientation and their association with upland habitat variables. On broad scales, the movement of aquatic species within the stream environment is limited to upstream and downstream migration. The inability of aquatic species to circumnavigate man-made obstacles causes them to be particularly vulnerable to habitat fragmentation. Habitat fragmentation has a major influence on species distribution and complicates distribution mapping. To better understand the spatial distributions of freshwater aquatic species in North Carolina, the Service created predictive habitat maps for 226 different aquatic species using geographic information systems (GIS) and maximum entropy (Maxent) modeling. These maps were derived by comparing known species occurrences with a suite of stream- or land-cover-derived environmental variables. -

Distribution Changes of Small Fishes in Streams of Missouri from The

Distribution Changes of Small Fishes in Streams of Missouri from the 1940s to the 1990s by MATTHEW R. WINSTON Missouri Department of Conservation, Columbia, MO 65201 February 2003 CONTENTS Page Abstract……………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………… 10 Methods……………………………………………………………………………….. 17 The Data Used………………………………………………………………… 17 General Patterns in Species Change…………………………………………... 23 Conservation Status of Species……………………………………………….. 26 Results………………………………………………………………………………… 34 General Patterns in Species Change………………………………………….. 30 Conservation Status of Species……………………………………………….. 46 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………….. 63 General Patterns in Species Change………………………………………….. 53 Conservation Status of Species………………………………………………. 63 Acknowledgments……………………………………………………………………. 66 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………………….. 66 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………… 72 FIGURES 1. Distribution of samples by principal investigator…………………………. 20 2. Areas of greatest average decline…………………………………………. 33 3. Areas of greatest average expansion………………………………………. 34 4. The relationship between number of basins and ……………………….. 39 5. The distribution of for each reproductive group………………………... 40 2 6. The distribution of for each family……………………………………… 41 7. The distribution of for each trophic group……………...………………. 42 8. The distribution of for each faunal region………………………………. 43 9. The distribution of for each stream type………………………………… 44 10. The distribution of for each range edge…………………………………. 45 11. Modified -

Rare Animals Tracking List

Louisiana's Animal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) ‐ Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Animals ‐ 2020 MOLLUSKS Common Name Scientific Name G‐Rank S‐Rank Federal Status State Status Mucket Actinonaias ligamentina G5 S1 Rayed Creekshell Anodontoides radiatus G3 S2 Western Fanshell Cyprogenia aberti G2G3Q SH Butterfly Ellipsaria lineolata G4G5 S1 Elephant‐ear Elliptio crassidens G5 S3 Spike Elliptio dilatata G5 S2S3 Texas Pigtoe Fusconaia askewi G2G3 S3 Ebonyshell Fusconaia ebena G4G5 S3 Round Pearlshell Glebula rotundata G4G5 S4 Pink Mucket Lampsilis abrupta G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Plain Pocketbook Lampsilis cardium G5 S1 Southern Pocketbook Lampsilis ornata G5 S3 Sandbank Pocketbook Lampsilis satura G2 S2 Fatmucket Lampsilis siliquoidea G5 S2 White Heelsplitter Lasmigona complanata G5 S1 Black Sandshell Ligumia recta G4G5 S1 Louisiana Pearlshell Margaritifera hembeli G1 S1 Threatened Threatened Southern Hickorynut Obovaria jacksoniana G2 S1S2 Hickorynut Obovaria olivaria G4 S1 Alabama Hickorynut Obovaria unicolor G3 S1 Mississippi Pigtoe Pleurobema beadleianum G3 S2 Louisiana Pigtoe Pleurobema riddellii G1G2 S1S2 Pyramid Pigtoe Pleurobema rubrum G2G3 S2 Texas Heelsplitter Potamilus amphichaenus G1G2 SH Fat Pocketbook Potamilus capax G2 S1 Endangered Endangered Inflated Heelsplitter Potamilus inflatus G1G2Q S1 Threatened Threatened Ouachita Kidneyshell Ptychobranchus occidentalis G3G4 S1 Rabbitsfoot Quadrula cylindrica G3G4 S1 Threatened Threatened Monkeyface Quadrula metanevra G4 S1 Southern Creekmussel Strophitus subvexus -

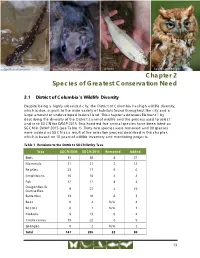

Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need

Spotted salamander Southern flying squirrel Alewife Eastern screech owl Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need 2.1 District of Columbia’s Wildlife Diversity Despite being a highly urbanized city, the District of Columbia has high wildlife diversity, which is due, in part, to the wide variety of habitats found throughout the city and a large amount of undeveloped federal land. This chapter addresses Element 1 by describing the diversity of the District’s animal wildlife and the process used to select and rank SGCN for SWAP 2015. Two hundred five animal species have been listed as SGCN in SWAP 2015 (see Table 1). Thirty-two species were removed and 90 species were added as SGCN as a result of the selection process described in this chapter, which is based on 10 years of wildlife inventory and monitoring projects. Table 1 Revisions to the District’s SGCN list by Taxa Taxa SGCN 2005 SGCN 2015 Removed Added Birds 35 58 4 27 Mammals 11 21 2 12 Reptiles 23 17 6 0 Amphibians 16 18 2 4 Fish 12 12 4 4 Dragonflies & 9 27 2 19 Damselflies Butterflies 13 10 6 3 Bees 0 4 N/A 4 Beetles 0 1 N/A 1 Mollusks 9 13 0 4 Crustaceans 19 22 6 9 Sponges 0 2 N/A 2 Total 147 205 32 90 13 Chapter 2 Species of Greatest Conservation Need 2.1.1 Terrestrial Wildlife Diversity The District has a substantial number of terrestrial animal species, and diverse natural communities provide an extensive variety of habitat settings for wildlife. -

Evaluation of Protected, Threatened, and Endangered Fish Species in Upper Bear Creek Watershed

ORNL/M-6567 ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES DIVISION EVALUATION OF PROTECTED, THREATENED, AND ENDANGERED FISH SPECIES IN UPPER BEAR CREEK WATERSHED M. G. Ryon Environmental Sciences Division Publication No. 4799 July 1998 Prepared for C. W. Hutzler Bechtel Jacobs LLC Prepared by the OAK RIDGE NATIONAL LABORATORY Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831-6285 managed by LOCKHEED MARTIN ENERGY RESEARCH CORP. for the U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY under contract DE-AC05-96OR22464 ABSTRACT The East Bear Creek Site for the proposed centralized waste facility on the U.S. Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge Reservation was evaluated for potential rare, threatened or endangered (T&E) fish species in the six primary tributaries and the main stem of Bear Creek that are within or adjacent to the facility footprint. These tributaries and portion of Bear Creek comprise the upper Bear Creek watershed. One T&E fish species, the Tennessee dace (Phoxinus tennesseensis), was located in these streams. The Tennessee dace is listed by the State of Tennessee as being in need of management, and as such its habitat is afforded some protection. Surveys indicated that Tennessee dace occupy the northern tributaries NT-1, NT-4, and NT-5, as well as Bear Creek. Several specimens of the dace were gravid females, indicating that the streams may function as reproductive habitat for the species. The implications of impacts on the species are discussed and mitigation objectives are included. INTRODUCTION Bear Creek is a third-order tributary of the East Fork Poplar Creek (EFPC), which flows westward from spring sources at the west end of the Oak Ridge Y-12 Plant.