DUB DATE 69 NOTE 154P. EDRS PRICE FDRS Price M7-$0.75 HC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health British Paediatric Surveillance Unit

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health British Paediatric Surveillance Unit 14th Annual Report 1999/2000 The British Paediatric Surveillance Unit always welcomes invitations to give talks describing the work of the Unit and makes every effort to respond to these positively. Enquiries should be directed to our office. The Unit positively encourages recipients to copy and circulate this report to colleagues, junior staff and medical students. Additional copies are available from our office, to which any enquiries should be addressed. Published September 2000 by the: British Paediatric Surveillance Unit A unit within the Research Division of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health 50 Hallam Street London W1W 6DE Telephone: 44 (0) 20 7307 5680 Facsimile: 44 (0) 20 7307 5690 E-mail: [email protected] Registered Charity No. 1057744 ISBN 1 900954 48 6 © British Paediatric Surveillance Unit British Paediatric Surveillance Unit - 14 Annual Report 1999-2000 Compiled and edited by Richard Lynn, Angus Nicoll, Jugnoo Rahi and Chris Verity Membership of Executive Committee 1999/2000 Dr Christopher Verity Chairman Dr Angus Clarke Co-opted Professor Richard Cooke Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Research Division Dr Patricia Hamilton Co-opted Professor Peter Kearney Faculty of Paediatrics, Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Dr Jugnoo Rahi Medical Adviser Dr Ian Jones Scottish Centre for Infection and Environmental Health Dr Christopher Kelnar Co-opted Dr Gabrielle Laing Co-opted Mr Richard Lynn Scientific Co-ordinator -

Hearing Before the Committee on Government Reform

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 466 915 EC 309 063 TITLE Autism: Present Challenges, Future Needs--Why the Increased Rates? Hearing before the Committee on Government Reform. House of Representatives, One Hundred Sixth Congress, Second Session (April 6,2000). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, DC. House Committee on Government Reform. REPORT NO House-Hrg-106-180 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 483p. AVAILABLE FROM Government Printing Office, Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office, Washington, DC 20402-9328. Tel: 202-512-1800. For full text: http://www.house.gov/reform. PUB TYPE Legal/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF02/PC20 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Autism; *Child Health; Children; *Disease Control; *Etiology; Family Problems; Hearings; *Immunization Programs; Incidence; Influences; Parent Attitudes; *Preventive Medicine; Research Needs; Symptoms (Individual Disorders) IDENTIFIERS Congress 106th; Vaccination ABSTRACT This document contains the proceedings of a hearing on April 6, 2000, before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Government Reform. The hearing addressed the increasing rate of children diagnosed with autism, possible links between autism and childhood vaccinations, and future needs of these children. After opening statements by congressmen on the Committee, the statements and testimony of Kenneth Curtis, James Smythe, Shelley Reynolds, Jeana Smith, Scott Bono, and Dr. Wayne M. Danker, all parents of children with autism, are included. Their statements discuss symptoms of autism, vaccination concerns, family problems, financial concerns, and how parents can be helped. The statements and testimony of the second panel are then provided, including that of Andrew Wakefield, John O'Leary, Vijendra K. Singh, Coleen A. Boyle, Ben Schwartz, Paul A. -

Management for Child Health Services

Management for Child Health Services JOIN US ON THE INTERNET VIA WWW, GOPHER, FTP OR EMAIL: WWW: http://www.thomson.com GOPHER: gopher.thomson.com !T\® A service of 1\.!JP FTP: ftp.thomson.com EMAIL: [email protected] Management for Child Health Services Edited by Michael Rigby Centre for Health Planning and Management Keele University Staffordshire UK Euan M. Ross King's College School of Medicine and Dentistry, London Mary Sheridan Centre for Child Health London UK and Norman T. Begg PHLS Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre London UK ~~nl Springer-Science+Business Media, B.V. Published by Chapman & Hall, 2-6 Boundary Row, London SEI SHN, UK First edition 1998 ©Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 1998 Originally published by Chapman & Hall in 1998. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1998 Typeset in 10/12 Palatino by Keyset Composition, Colchester ISBN 978-0-412-59660-5 ISBN 978-1-4899-3144-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4899-3144-3 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the UK Copyright Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may not be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction only in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency in the UK, or in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the appropriate Reproduction Rights Organization outside the UK. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the terms stated here should be sent to the publishers at the London address printed on this page. -

Bad Medicine: Parents, the State, and the Charge of “Medical Child Abuse”

Bad Medicine: Parents, the State, and the Charge of “Medical Child Abuse” ∗ Maxine Eichner † Doctors and hospitals have begun to level a new charge — “medical child abuse” (MCA) — against parents who, they say, get unnecessary medical treatment for their kids. The fact that this treatment has been ordered by other doctors does not protect parents from these accusations. Child protection officials have generally supported the accusing doctors in these charges, threatening parents with loss of custody, removing children from their homes, and even sometimes charging parents criminally for this asserted overtreatment. Judges, too, have largely treated such charges as credible claims of child abuse. ∗ Copyright © 2016 Maxine Eichner. Graham Kenan Distinguished Professor of Law, University of North Carolina School of Law; J.D., Ph.D. I am grateful for comments from and conversations with an interdisciplinary group of readers: Alexa Chew, J.D.; Christine Cox, J.D.; Hannah Eichner; Keith Findley, J.D.; Victor Flatt, J.D.; Michael Freeman, M.D., Ph.D., M.P.H.; Steven Gabaeff, M.D.; Mark Graber, M.D.; Heidi Harkins, Ph.D.; Clare Huntington, J.D.; Diana Rugh Johnson, J.D.; Joan Krause, J.D.; Michael Laposata, M.D., Ph.D.; Holning Lau, J.D.; Sue Luttner; Beth Maloney, J.D.; Loren Pankratz, Ph.D.; Maya Manian, J.D.; Rachel Rebouche, J.D.; Diane Redleaf, J.D.; Maria Savasta-Kennedy, J.D.; Richard Saver, J.D.; Jessica Shriver, M.A., M.S.; Adam Stein, J.D.; Eric Stein, J.D.; Beat Steiner, M.D., M.P.H.; Judy Stone, M.D.; Deborah Tuerkheimer, J.D.; Catherine Volponi, J.D; and Deborah Weissman, J.D. -

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health British Paediatric Surveillance Unit

Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health British Paediatric Surveillance Unit 15th Annual14th14Annual Report Report 2000-2001 1998/99 The British Paediatric Surveillance Unit (BPSU) welcomes invitations to give talks on the work of the Unit and takes every effort to respond positively. Enquiries should be made direct to the BPSU office. The BPSU positively encourages recipients to copy and circulate this report to colleagues, junior staff and medical students. Additional copies are available from the BPSU office, alternatively the report can be viewed via the BPSU website. Published September 2001 by the: British Paediatric Surveillance Unit A unit within the Research Division of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health 50 Hallam Street London W1W 6DE Telephone: 44 (0) 020 7307 5680 Facsimile: 44 (0) 020 7307 5690 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://bpsu.rcpch.ac.uk Registered Charity no 1057744 ISBN 1-900954-54-0 © British Paediatric Surveillance Unit British Paediatric Surveillance Unit – Annual Report 2000-2001 Compiled and edited by Richard Lynn, Hilary Kirkbride, Jugnoo Rahi and Chris Verity, September 2001 Membership of Executive Committee 2000/2001 Dr Christopher Verity Chair Dr Angus Clarke Professor Richard Cooke Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Research Division Mrs Linda Haines Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health Research Division Dr Patricia Hamilton Dr Ian Jones Scottish Centre for Infection and Environmental Health Professor Peter Kearney Faculty of Paediatrics, Royal College of Physicians -

Download Pdf 1012.1 KB APCP Newsletter

ASSOCIATION OF PAEDIATRIC CHARTERED PHYSIOTHERAPISTS In this issue : The GAITRite® mat as a quantitative measure of dynamic walking balance in children with coordination problems. Obese children: causes, consequences, challenges Lycra Garments – A single case study ISSUE MARCH 2006 NO. 118 NATIONAL COMMITTEE OFFICERS AND MEMBERS REGIONAL & SUB-GROUP REPRESENTATIVES CHAIRMAN Lesley Smith Physiotherapy Dept [email protected] EAST ANGLIA LONDON SCOTLAND Royal Hospital for Sick Children York Hill NHS Trust, Dalnair St GLASGOW G3 8 SJ Stephanie Cawker Alison Gilmour VICE-CHAIRMAN Peta Smith Physiotherapy Dept [email protected] The Wolfson Centre Physiotherapy Dept Mary Sheridan Centre Mecklenburgh Square Braidburn School 43 New Dover Rd CANTERBURY CT1 3AT LONDON 107 Oxgangs Rd North WC1N 2AP EDINBURGH EH14 1ED SECRETARY Laura Wiggins 26 Braidpark Drive [email protected] Giffnock [email protected] [email protected] GLASGOW G46 6NB TREASURER Fiona Down 5 Home Farm Close [email protected] Hilton SOUTH WEST SOUTH EAST WALES HUNTINGDON Cambs PE28 9QW PUBLIC RELATIONS Lindsay Rae Physiotherapy Dept. [email protected] Lynda New Ann Martin Diane Rogers OFFICER The Children’s Hospital Physiotherapy Dept Childrens Therapy Centre Head of Children’s Physiotherapy Steelhouse Lane BIRMINGHAM B4 6NH Milestone School Goldie Leigh Room 386 Lonford Lane LODGE HILL Paediatrics North Corridor VICE PUBLIC Chris Sneade Child Development Centre [email protected] RELATIONS OFFICER Alder Hey Children’s -

As Clinics Collapse, a Rift in Trust Trump’S Camp Sunday, with Prospect of a Reprieve

ABCDE Prices may vary in areas outside metropolitan Washington. SU V1 V2 V3 V4 Cloudy, rain 36/33 • Tomorrow: Morning rain, breezy 53/26 B8 Democracy Dies in Darkness MONDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 2021 . $2 Many GOP Acquittal o∞cials see Inside the rise and swift downfall of P hiladelphia’s mass vaccination start-up virus relief widens as a lifeline divide Mayors, governors say in GOP Biden’s proposal i s vital to blunt economic pain FACTIONS SPLIT O N PATH FORWARD BY GRIFF WITTE Graham sees Trump as the ‘most potent force’ The pandemic has not been kind to Fresno, the poorest major city in California. The unemploy- BY AMY B WANG ment rate spiked above 10 per- cent and has stubbornly re- One day after the Senate ac- mained there. Violent crime has quitted former president Donald surged, as has homelessness. Tax Trump in his second impeach- revenue has plummeted as busi- ment trial, Republicans contin- nesses have shuttered. Lines at ued to diverge in what the future food banks are filled with first- of their party should be, with a timers. chasm widening between those But as bad as it’s been, things who want nothing to do with the could soon get worse: Having former president and those who frozen hundreds of jobs last year, openly embrace him. The divi- the city is now being forced to sion is playing out as Trump consider laying off 250 people, promises a return to politics and including police and firefighters, as both factions within the GOP to close a $31 million budget vow they will prevail in the 2022 shortfall. -

Friend and Family Search - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

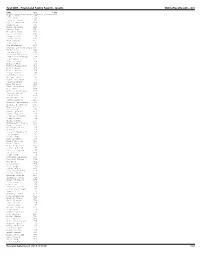

Test 2005 - Friend and Family Search - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Sophie Walker F70 Jill Kohla F46 Diana Bruckner F70 Justin Laughlin M38 Ruifang Li F43 Micah Sterling M26 Gianna Terra F9 Meredith Linde F25 Carter Wilson M9 Karen Vicsik F35 Darin Parks M42 mike webster M37 Jiyu Kim F8 Jed MacArthur M38 Stryder Lafone-Demaroi M8 Ed McDevitt M40 Don McJunkin M68 Kristina Wilcoxson F23 Debbie Eichelberger F35 Jay Tippets M35 Jennifer Hart F39 Angela Upton F31 Autumn Warrington F37 Ashley Henkle F36 Nicole Martin F29 Tracy Hansen F61 Samantha Lucero F44 Whitney Shaw F28 Joanne Sorensen F73 Julia Brabant F32 Lisa Thorson F32 Julia Ostrander F15 Nate Muniz M26 Andreas Muschinski M51 Kathryn Ferrel F19 Jon Collis M39 Marina Griffin F9 Justin Bartsch M13 Kaitlyn Blackburn F14 Charlie Heathwood M9 Wyatt Schroth M12 Helen Wright F73 Ylann goresko M13 Lynne Ferguson F43 Lindsay Fetherman F26 Cindy Worster F49 Sheri Nemeth F57 Maximillian Mosier M13 Jasmine Szabo F15 Christine Nelson F35 Min Kim F18 Misty Hildenbrand F27 Deb Hargens F62 Kristi Wade F45 Alys Brockway F48 Audrey Russell F37 Lula DeMars F11 Roger Lapthorne M58 Denise Ashford F53 Carol Finlayson F56 Keith Elliott M29 Linda Ward F59 Catherine Williams F20 Rachelle Fuller F42 Amy Hood F12 Sarah Mooney F16 Beth Brady F58 Rodney Glenn M52 Jacy Kruckenberg F39 Jeffrey Machell M53 William Kohnert M17 Stephanie Ayers F26 Judith W Warner F66 Katie Gann F19 Ginny Page F70 Jennifer Chavez F28 Catherine Trippett F54 Magali Lutz F42 Chandler -

Final Program

Final Program Quality of Life: Advancing Measurement Science and Transforming Healthcare www.isoqol.org HOTEL FLOOR PLAN HALL II HALL I Poster Hall Plenary Hall Desk Registration Registration ISOQOL 21ST ANNUAL CONFERENCE 15-18 October, 2014 Berlin, Germany Quality of Life: Advancing Measurement Science and Transforming Healthcare Welcome to the 21st Annual Conference of the International Society for Quality of Life Research, 15-18 October, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome from the Program Chairs ..............................................2 Plenary Speakers ...............................................................................16 Schedule at a Glance ...........................................................................3 ............................................................................20 General Conference Information ...................................................6 Wednesday, 15 October .........................................................20 About ISOQOL ........................................................................................8 ScientificThursday, Program 16 October .............................................................23 Programs and Projects ..............................................................8 Friday, 17 October ....................................................................41 ISOQOL Membership .................................................................8 Saturday, 18 October ..............................................................60 ISOQOL Leadership -

Test 2005 - Friend and Family Search - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

Test 2005 - Friend and Family Search - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Fred Buehler M48 Brina Larson F44 Mark Buckner M61 Ryan Falor M33 Tom Reardon M14 Ricardo Sigala M29 christy bohnstengel F46 Blythe Truhe F9 Taylor Tancik F26 Alex Duymelinck M10 Amanda kuzbiel F10 Munib Far M17 Louise Sternberg F49 Lauren Lumley F22 Brandon Pitzer M34 Travis Wall M27 katelyn kinson F16 Mike Jarvis M48 Megan Page F31 David Groover M23 James VInall M36 Doug Wright M28 Alex Kapetanovic M34 Kellen Cooper-Sansone M24 Matt Finnigan M45 Meg Daker F34 Katie Collins F14 Ellie Wells F19 Alison Hamilton F20 Benjamin Hays M14 Kasey Grohe F42 Mark Soderberg M53 Jared Semkoff M26 Mark Wade M37 Matt Mroz M42 Bob Nelson M73 Nancy Perez-Vasquez F11 Patrick Walker M39 Scott Miller M45 Patti Lee F55 Dennis MIller M64 Narinton McKinley F46 Koleby Potter F29 Maggie Stephens F16 Jon Saints M34 Daniel Jenkins M46 keeli finan F12 criselda sanchez F32 Brandy Unruh F33 Kirankumar Madiraju M44 Tyler Gazzam M11 Abigail Humphreys F35 jon mcdaniel M68 Stephanie McKay F66 Max Mandelstam M21 brynn macinnis F22 Nick Boggess M13 Ben Jansen M46 Rebecca Kottenstette F33 Allanah Poindexter F8 Alexandra Sieh F26 Steven Engleman M64 Elizabeth Knispel F31 McEwen Johnson-Hernan M7 Carl Campbell M11 Jim Sawtelle M48 Kris Thomsen M21 Tara Wilson F30 Erica Stetson F48 Evan Horowitz M12 David Meaders M37 Sheridan Wright M29 Vikki Connor F46 Andrew Nong M15 Kyle Power M27 Michelle Heim F36 Lilian Sosa F25 Daniel Hahn M30 Carmel Ulbrick F29 -

The Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies ANNUAL REPORT Cornell University

The Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies ANNUAL REPORT 1991 Cornell University ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS All complex reports require a collective effort. Our first thanks go to the many professors, program directors, administrators, and staff members whose time, expertise, and creativity give the Einaudi Center so much to report about. The idea to produce a full-scale report on the Einaudi Center for broad distribution came from Executive Director, John M. Kubiak. He has followed it through with characteristic thoroughness and efficiency. Hannah Messerli was responsible for much of the gathering and collating of data, the collection of written materials from the programs, and for drafting many sections. Her energy, competence, and good spirits made this project move ahead smoothly. Kenna March has handled the complex desktop publishing tasks associated with this report with characteristic aplomb and goodwill, contributing both to the printed form and the substance of the report in many ways. Donna Eschenbrenner did an excellent job of copy editing. Anyone interested in additional information about international programs or opportunities at Cornell University is invited to contact the Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies: Mario Einaudi Center for International Studies 170 Uris Hall Cornell University Ithaca, NY 14853-7601 Telephone: (607) 255-6370 Fax: (607) 254-5000 CONTENTS Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................................... -

International Directory March 2016

International Directory March 2016 Moore Stephens International Limited Contact Names: Chairman Richard Moore [email protected] Chief Operating Officer Michael Hathorn [email protected] Director of Sales Charlie Newby [email protected] International Liaison Manager Sarah Skeels-Smith [email protected] Senior International Administrator Heather Deacon [email protected] Marketing Manager Victoria Littler [email protected] Marketing Executive Janice Moreland [email protected] 150 Aldersgate Street London EC1A 4AB England, U.K. Telephone: +44 (0) 20 7334 9191 Facsimile: +44 (0) 20 7651 1637 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.moorestephens.com Business Development Leon Hou [email protected] 20F Yueda Plaza 889 Wanhangdu Road Jing’an District Shanghai 200042 The People’s Republic of China Telephone: +86 (21) 6290 5855 Facsimile: +86 (21) 6290 5899 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.moorestephens.com CONTENTS Introduction 2 Committees 5 Regional Executive Offices 7 Index 11 International Direct Dialling Codes 18 World Time Zones 19 2016/2017 Calendar 20 Member Firms 21 Correspondent/Associated Firms 218 E-mail Country Codes 226 Personal Contact Details 227 WORLDWIDE STATISTICS Fee Members and Principals income correspondents Countries Firms Offices and staff US$m Africa 6 20 25 852 26.5 Asia Pacific region 15 25 56 3,434 88.5 Australasia region 2 15 22 791 98.2 China region 1 4 48 4,922 304.0 Europe region