1 Participatory Development and Disaster Risk Reduction And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Government of Albay and the Center for Initiatives And

Strengthening Climate Resilience Provincial Government of Albay and the SCR Center for Initiatives and Research on Climate Adaptation Case Study Summary PHILIPPINES Which of the three pillars does this project or policy intervention best illustrate? Tackling Exposure to Changing Hazards and Disaster Impacts Enhancing Adaptive Capacity Addressing Poverty, Vulnerabil- ity and their Causes In 2008, the Province of Albay in the Philippines was declared a "Global Local Government Unit (LGU) model for Climate Change Adapta- tion" by the UN-ISDR and the World Bank. The province has boldly initiated many innovative approaches to tackling disaster risk reduction (DRR) and climate change adaptation (CCA) in Albay and continues to integrate CCA into its current DRM structure. Albay maintains its position as the first mover in terms of climate smart DRR by imple- menting good practices to ensure zero casualty during calamities, which is why the province is now being recognized throughout the world as a local govern- ment exemplar in Climate Change Adap- tation. It has pioneered in mainstreaming “Think Global Warming. Act Local Adaptation.” CCA in the education sector by devel- oping a curriculum to teach CCA from -- Provincial Government of Albay the primary level up which will be imple- Through the leadership of Gov. Joey S. Salceda, Albay province has become the first province to mented in schools beginning the 2010 proclaim climate change adaptation as a governing policy, and the Provincial Government of Albay schoolyear. Countless information, edu- cation and communication activities have (PGA) was unanimously proclaimed as the first and pioneering prototype for local Climate Change been organized to create climate change Adaptation. -

Philippines and Elsewhere May 20, 2011

INVESTMENT CLIMATE IMPROVEMENT PROJECT NEWSCLIPS Economic Reform News from the Philippines and Elsewhere May 20, 2011 Philippines Competitiveness goal set Business World, May 16, 2011 Emerging markets soon to outstrip rich ones, Eliza J. Diaz says WB Philippine Daily Inquirer, May 18, 2011 COMPETITIVENESS planners have set an Michelle V. Remo ambitious goal of boosting the Philippines’ global ranking in the next five years, highlighting Emerging economies like the Philippines will the need for sustained government interventions play an increasingly important role in the global if the country is to rise up from its perennial economy over the medium to long term, bottom half showings. continually exceeding growth rates of industrialized nations and accounting for bigger shares of the world’s output. Train line to connect Naia 3, Fort, Makati Philippine Daily Inquirer, May 18, 2011 Paolo G. Montecillo Gov’t to ask flight schools to move out of Naia Philippine Daily Inquirer, May 18, 2011 A new commuter train line may soon connect the Paolo G. Montecillo Ninoy Aquino International Airport (Naia) terminal 3 to the Fort Bonifacio and Makati The government has given flight schools six central business districts, according to the Bases months to submit detailed plans to move out of Conversion and Development Authority Manila’s Ninoy Aquino International Airport (BCDA). (Naia) to reduce delays caused by congestion at the country’s premier gateway. Mitsubishi seeks extension of railway bid Business Mirror, May 17, 2011 LTFRB gets tough on bus firms resisting gov’t Lenie Lectura inventory Philippine Daily Inquirer, May 18, 2011 MITSUBISHI Corp., one of the 15 companies Paolo G. -

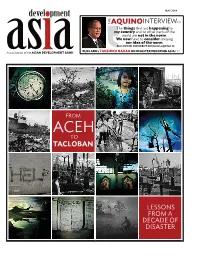

From Aceh to Tacloban: Lessons from A

MAY 2014 P.18 THE AQUINOINTERVIEW The things that are happening to my country and to other parts of the world are not in the norm. We now have to consider revising our idea of the norm. PHILIPPINES PRESIDENT BENIGNO AQUINO III A publication of the ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK PLUS ADB’s TAKEHIKO NAKAO ON DISASTER PROOFING ASIA P.34 FROM ACEH TO TACLOBAN LESSONS FROM A DECADE OF DISASTER Work for Asia and the Pacifi c. Work for ADB. The only development bank dedicated to Asia and the Pacifi c is hiring people dedicated to development. ADB seeks highly qualifi ed individuals for the following vacancies: ƷɆ*!.#5ɆƷɆ%**%(Ɇ*#!)!*0ɆƷɆ%**%(Ɇ!0+.ɆƷɆ.%20!Ɇ!0+.Ɇ%**!Ɇ ƷɆ"!#1. /ɆƷɆ.*/,+.0ɆƷɆ0!.Ɇ1,,(5Ɇ* Ɇ*%00%+* +)!*Ɇ.!Ɇ!*+1.#! Ɇ0+Ɇ,,(5Ɓ +.Ɇ)+.!Ɇ !0%(/ƂɆ2%/%0Ɇ333Ɓ Ɓ+.#Ɲ.!!./ ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Inside MAY 2014 P.18 SPECIAL REPORT THE AQUINOINTERVIEW The things that are happening to my country and to other parts of the world are not in the norm. We now have to consider revising our idea of the norm. PHILIPPINES PRESIDENT BENIGNO AQUINO III PLUS ADB’s TAKEHIKO NAKAO ON DISASTER PROOFING ASIA P.32 A publication of the ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK From Aceh to Tacloban 31 Aid Watch A rising tide of disasters has 8 What have we learned from a spurred a sharper focus on FROM decade of disaster? how aid is used ACEH TO TACLOBAN 17 Taking Cover 34 Opinion: Asia needs more protection against Takehiko Nakao the financial cost of disaster ADB President LESSONS says disaster FROM A DECADE OF DISASTER Cover Photos : Gerhard Joren (Tacloban; color); Veejay Villafranca risk will check (Tacloban; black and white); Getty Images (Aquino) Asia’s growth 32 We cannot allow the cycle of destruction and reconstruction to continue by rebuilding communities in the exact same manner. -

Philippine Political Circus

3/18/2010 THE SILLY SEASON IS UPON US 53 DAYS TO GO AND THE SUPREME COURT IS ALREADY IN THE GAME WITH US TODAY G1BO TEODORO HE’S NOT SO SILLY QRT POL / CHART 1 MARCH 2010 Philippine Political Circus The Greatest Show on Earth 53 DAYS TO GO QRT POL / CHART 2 MARCH 2010 1 3/18/2010 ELECTION QUICKFACTS POSITIONS AT STAKE 1 PRES, 1 VP, 12 SENATORS, 250 REPS, 17,600+ LOCAL GOV’T POSTS NUMBER OF CANDIDATES 90,000+ NUMBER OF REGISTERED VOTERS 50.7 MILLION (SAME NUMBER OF BALLOTS TO BE PRINTED) WINNING BIDDER FOR THE 2010 SMARTMATIC-TIM AUTOMATION ELECTION PROJECT FORWARDERS TASKED TO DEPLOY GERMALIN ENTERPRISES (NCR), ARGO FORWARDERS ELECTION MATERIALS (VISAYAS & MINDANAO), ACE LOGISTICS (SOUTHERN & NORTHERN LUZON) NUMBER OF UNIQUE BALLOTS 1,631 (CORRESPONDS TO PRECINCT -SPECIFIC BALLOTS PER CITY/MUNICIPALITY) BALLOT SIZE 26 INCHES LONG AND 8.5 INCHES WIDE TOTAL NUMBER OF CLUSTERED 75,471 PRECINCTS (COMBINED 5-7 PRECINCTS) NUMBER OF VOTERS PER PRECINCT 1, 000 MAXIMUM OFFICIAL CITIZEN’S ARM ÆPARISH PASTORAL COUNCIL FOR RESPONSIBLE VOTING (PPCRV) ÆNAMFREL NOT ACCREDITED BUT FIGHTING FOR IT SYSTEM OF VALIDATION RANDOM MANUAL PRECINCT AUDIT TO ENSURE THAT THERE WILL BE NO DISCREPANCY IN THE PCOS COUNT (1 PRECINCT PER CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT) ELECTION-RELATED KILLINGS 69 AS OF MARCH 2010, 141 IN ‘07, 189 IN ’04, 132 IN ‘01, 82 IN ’98, 89 IN ‘92 QRT POL / CHART 3 MARCH 2010 PHILIPPINE ELECTION HISTORY IN BRIEF ELECTION YEAR MAJOR FEATURES 1986 h SNAP ELECTION, IRREGULAR ELECTION h CORY WON IN THE VOTING – BUT LOST IN THE OFFICIAL COUNTING h REVOLUTION FOLLOWED 2 WEEKS LATER h GOOD VS. -

Pnoy Inaugurates BUCM Building, Calls BU a World Class University

ISSN 2094-3991 VOLUME 6, ISSUE 5 SUMMER 2014 Pres. Benigno S Aquino III leads the inauguration of the BU Heath Sciences Building and the launching of the MD-MPA Program of the BU College of Medicine held on May 19, 2014 Earl Recamunda THE PRESIDENT’S OUTBOX Even the PNoy inaugurates BUCM building, exceptional heat we have all endured this summer calls BU a world class university President Benigno education that Bicol University Governor Salceda. of 2014 has not withered S. Aquino III inaugurated on is now known for. BUCM will offer a Bicol University’s garden, May 19 the newly completed “Talaga naman pong double-course program, to which has remained BU Health Sciences Building world-class ang kahusayan ng produce graduates of Doctor to be abundant with which will house the first Bicol University,” he stated. of Medicine and Master in state-run medical school Her dream since Public Administration major in achievements, topped in the Bicol region, the the start of her term, BUCM Health Emergency and Disaster by the inauguration Bicol University College of has become one of BU Management (MD-MPA). Its and launch of the Bicol Medicine (BUCM). President Lauraya’s greatest In his speech during achievements in her 8-year, start this June, to hold classes University College of the event, he expressed his 2-term administration which firstat the batch newly ofinaugurated students andwill Medicine! admiration for the progress ends in March 2015. The blessed BU Health Sciences Having His he has seen in the Province realization of this dream, she of Albay under the leadership said, was made possible because applicants is on-going, with a Excellency Benigno S. -

Asamblea General Distr

NACIONES UNIDAS A Asamblea General Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/8/3/Add.2 16 de abril de 2008 ESPAÑOL Original: INGLÉS CONSEJO DE DERECHOS HUMANOS Octavo período de sesiones Tema 3 de la agenda PROMOCIÓN Y PROTECCIÓN DE TODOS LOS DERECHOS HUMANOS, CIVILES, POLÍTICOS, ECONÓMICOS, SOCIALES Y CULTURALES, INCLUIDO EL DERECHO AL DESARROLLO Informe del Relator Especial sobre las ejecuciones extrajudiciales, sumarias o arbitrarias, Philip Alston Adición* MISIÓN A FILIPINAS * Sólo el resumen del presente informe se somete a los servicios de edición y se distribuye en todos los idiomas oficiales. El informe propiamente dicho, que figura en el anexo al resumen, y los apéndices se distribuyen tal como se recibieron. GE. 08-13004 (S) 300408 050508 A/HRC/8/3/Add.2 página 2 Resumen En los últimos seis años se han producido numerosas ejecuciones extrajudiciales de activistas de izquierda en Filipinas. Con esas muertes se ha eliminado a dirigentes de la sociedad civil, incluidos defensores de los derechos humanos, sindicalistas y partidarios de la reforma agraria, se ha intimidado a un gran número de agentes de la sociedad civil y se ha restringido el discurso político en el país. Dependiendo de quién cuenta y cómo lo hace, el número total de ejecuciones se sitúa entre 100 y más de 800. La estrategia de contrainsurgencia y los recientes cambios en las prioridades del sistema de justicia penal revisten especial importancia para entender por qué se siguen produciendo esas muertes. En el Gobierno, muchos han llegado a la conclusión de que varias organizaciones de la sociedad civil son "frentes" del Partido Comunista de Filipinas y su grupo armado, el Nuevo Ejército del Pueblo. -

ISSN 2094-9383 a Quarterly Magazine of the City Government of Naga Bikol, Philippines New ISSN 2094-9383 JOHN G

ISSN 2094-9383 A Quarterly Magazine of the City Government of Naga Bikol, Philippines New ISSN 2094-9383 JOHN G. BONGAT Advocacy Mayor GABRIEL H. BORDADO, JR. of a Vice Mayor Jose B. Perez Editor (on leave) Strong Alec Francis A. Santos Leadership Executive Editor Jason B. Neola Managing Editor NAGA IS DEFINED by an empowered and a more liveable community. A City we can truly Reuel M. Oliver Florencio T. Mongoso, Jr. responsible citizenry in action. call Maogmang Naga. A happy place inhabited by a happy people. Allen L. Reondanga Editorial Consultants This is the essence behind KKDK, the new advocacy of a strong leadership under Mayor These ideals are summed up in his first State of Jan Rev L. Davila John G. Bongat that inspires Nagueños to develop the City Report delivered on January 25. His main Stephen V. Prestado Layout Artists in their heart and mind a culture of cleanliness message is everyone, young or old, rich or poor, is (Kalinigan), peace (Katoninongan), and order part and parcel of the City’s life and future with the Ray John B. Ubaldo 2 (Disiplina). These, he believes, are the essential bounden duty to “H ELP your CiTy”, as everyone Graphic Artist takes part in defining Naga’s future today. ingredients (Kaipuhan) towards the attainment of Contents Randy Villaflor Jose B. Collera Photographers Albert F. Cecilio Highlights Alnor Roger Alcala Editorial Assistants STATE OF THE CITY REPORT (Jul - Dec 2010) Mayor JB delivers first SOCR This magazine is published by the City Government of Naga thru the 7 City Publications and External SALOG KAN BUHAY Relations Office (CPERO), with Broadbased support for Editorial Office at 1st floor, DOLE Naga River Project affirmed Bldg., City Hall Complex, J. -

Welcome Remarks by Executive Secretary, Office of the President, the Philippines

___________________________________________________________________________ 2014/ISOM/SYM/002 Session: Opening Welcome Remarks by Executive Secretary, Office of the President, the Philippines Submitted by: The Philippines Symposium on APEC 2015 Priorities Manila, Philippines 8 December 2014 Welcome Remarks of Executive Secretary Paquito N. Ochoa Jr. at the APEC [Delivered at the Grand Ballroom, Makati Shangri-La Hotel, Makati City, on December 8, 2014] His and Her Excellencies, the members of the Diplomatic Corps, the Senior Officials and delegates of the APEC member economies; fellow officials and workers in government; representatives from the APEC Business Advisory Council and the private sector; and the APEC Regional Secretariat, a good morning to all of you, and welcome to the Philippines and the first leg of our country’s hosting of the 2015 APEC. Please allow me to begin by enjoining everyone to join our people in prayer, as our countrymen in the Visayas, parts of Mindanao, and the Bicol Region are now feeling the effects of Typhoon Ruby. Our thoughts and prayers go to them, and to the men and women who have been mobilized to ensure their safety. It was with this typhoon in mind that we decided last week to move the venue of this Informal Senior Officials’ Meeting from the province of Albay to Metro Manila. We would have preferred to hold this meeting in the shadows one of the country’s most majestic sights, Mayon Volcano, but we believed it was more prudent for the local government of Albay––internationally recognized for its accomplishments in disaster risk reduction and management––to focus on the preventive actions they needed to undertake in the wake of the typhoon. -

May 23, 2015 Hawaii Filipino Chronicle 1

may 23, 2015 haWaII fILIpIno chronIcLe 1 ♦ MAY 23, 2015 ♦ CANDID PERSPECTIVES IMMIGRATION GUIDE MAINLAND NEWS Do fILIpIno In ImmIgratIon, Who hIrono IntroDuces LIves reaLLy has the greatest BILLs to Improve matter? Love of aLL? veterans' heaLth care PRESORTED HAWAII FILIPINO CHRONICLE STANDARD 94-356 WAIPAHU DEPOT RD., 2ND FLR. U.S. POSTAGE WAIPAHU, HI 96797 PAID HONOLULU, HI PERMIT NO. 9661 2 haWaII fILIpIno chronIcLe may 23, 2015 EDITORIALS FROM THE PUBLISHER Publisher & Executive Editor eather forecasters are pre- Charlie Y. Sonido, M.D. dicting a busier than normal QMC-West Marks Publisher & Managing Editor hurricane season for Hawaii. Chona A. Montesines-Sonido 1st Anniversary With five to eight storms ex- pected this June through No- Associate Editors he first year of any endeavor in life—be it a rela- W Dennis Galolo vember 2015, we urge you to tionship, business venture or even a child’s first Edwin Quinabo refrain from waiting until the very last birthday—is usually fraught with difficult chal- Contributing Editor minute to prepare. If you hate spending your lenges that threaten its very survival. The new Belinda Aquino, Ph.D. hard earned money on expensive bottled water, consider pur- Queen’s Medical Center-West Oahu quietly Creative Designer T chasing the waterBOB—a water containment system that holds Junggoi Peralta marked its first anniversary, managing to not only up to 100 gallons of fresh drinking water in a standard bathtub survive the initial growing pains but to also thrive. in the event of an emergency. Curious? Google “waterBOB” and Photography The success of Queen’s Health System’s new satellite cam- Tim Llena read more. -

![Contents [Edit] Term](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7280/contents-edit-term-4267280.webp)

Contents [Edit] Term

Economic development is a term that generally refers to the sustained, concerted effort of policymakers and community to promote the standard of living and economic health in a specific area. Such effort can involve multiple areas including development of human capital, critical infrastructure, regional competitiveness, environmental sustainability, social inclusion, health, safety, literacy, and other initiatives. Economic development differs from economic growth. Whereas economic development is a policy intervention endeavor with aims of economic and social well-being of people, economic growth is a phenomenon of market productivity and rise in GDP. Consequently, as economist Amartya Sen points out: ―economic growth is one aspect of the process of economic development.‖ [1] Contents [hide] 1 Term 2 Social Science Research 3 Goals 4 Regional policy o 4.1 Organization o 4.2 International Economic Development Council 5 Community Competition 6 See also 7 References [edit] Term The scope of economic development includes the process and policies by which a nation improves the economic, political, and social well-being of its people.[2] The University of Iowa's Center for International Finance and Development states that: 'Economic development' is a term that economists, politicians, and others have used frequently in the 20th century. The concept, however, has been in existence in the West for centuries. Modernization, Westernization, and especially Industrialization are other terms people have used when discussing economic development. -

ALBAY HEALTH STRATEGY Albay MDG Achievements

Story Line ALBAY HEALTH STRATEGY . Albay MDG Achievements towards SAFE AND SHARED . Albay Health Strategies DEVELOPMENT MDG – make it a MDG is all about goal, the rest follows dignity. Engaging dignity, Empoweri Governor Joey Sarte Salceda ng dignity Province of Albay Ennobling dignity MDGs are achieved ahead of 2015 exc. MDG 2 and 7 Goal Indicator Bicol Region Albay Achievements on MDG, 2009 1 Poverty Incidence MH Proportion of 0 - 5 years old who are malnourished Subsistence Incidence HH 25 24% Underweight (IRS) HH 2 Participation - Elementary LM 22 Cohort survival - elementary ML 20 3 Gender parity - elementary HH 4 Under-five mortality HH 16 Infant mortality H H 15 Proportion of fully-immunized children MH 5 Maternal mortality rate LH Contraceptive prevalence rate LM 10 Condom use rate LM 6 Deaths due to TB LH Malaria positive cases HH 5 7 Household with access to sanitary toilets HL Household with access to safe drinking water HH 0 Legend: 1992 2009 L low probability H high probability M medium probability no data Achievements on MDG, 2009 Achievements on MDG, 2009 Maternal Mortality Ratio Infant Mortality Rate 35 140 133 33 120 30 100 25 90/ 100,000 LB 80 20 60 59 15 17/1,000 LB 12 40 10 20 5 0 1998 2009 0 1998 2009 1 Achievements on MDG, 2009 Achievements on MDG, 2009 Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel Proportion of facility-based deliveries 100 100 90 90 90 88 80% 80 80% 80 70 70 60 60 50 50 40 40 30 29 30 20 20 10 10 11 0 1998 2009 0 1998 2009 Achievements on MDG, 2009 Achievements on MDG, 2009 Contraceptive -

The Daily Dispatch

The Daily Dispatch October 21, 2019 Feb. 2, 2017 Philippine Stock Market Update TODAY’S TOP NEWS DOTr chief says no to further review of MM subway Transportation Secretary Arthur Tugade said the P350- billion Metro Manila subway project would proceed as planned despite cost issues raised by Sen. Grace Poe, chair of the powerful Committee on Public Services. Bananas in trade deadlock between PH, South Korea Previous Close: 1 Yr Return: The Philippines is no longer confident it would finish a free 7,885.23 11.72% trade deal with South Korea by the deadline in Nov, as challenges remain unresolved on both sides. Trade and Open: YTD Return: Industry Secretary Ramon Lopez said they would still try to 7,874.80 5.24% get the free trade agreement signed next month. He said they 52-Week Range: Source: would continue pursuing the talks even past the deadline. 6,820.22 - 8,419.59 Bloomberg Dominguez open to wealth tax on mining revenues Foreign Exchange The head of the Duterte administration’s economic team is As of Oct. 18, 2019 open to Albay Rep. Joey Salceda’s proposal to slap a US Dollar Philippine Peso sovereign wealth tax on mining revenues. “The idea of a sovereign fund is actually a good idea…Funding something 1 51.255 like this from taxes on irreplaceable resources, I think it’s a good idea,” Finance Sec. Dominguez told reporters recently. PDST-R2 Rates As of Oct. 18, 2019 Alveo Land unveils 120-ha mixed-use estate Ayala-owned property developer Alveo Land has unveiled a Tenor Rate new commercial district in Biñan, Laguna, as part of its 1Y 3.6370 mixed-use estate called “Broadfield,” bringing to the 3Y 4.0500 property market P18 billion worth of fresh commercial lot 5Y 4.3130 inventory.