Medical Informatics—The State of the Art in the Hospital Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Scan Data

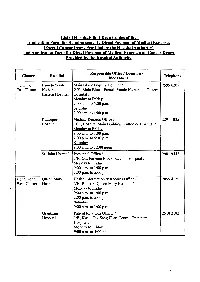

List of Hosoitals that Keep Copies of the Application Form for Reimbursement I Direct Payment of Medical Expenses (Except Cancer Drugs Provided by the Hospital Authority) and Application Form for Direct Payment of Medical Expenses on Cancer Drugs Provided by the Hospital Authority Responsible Office I Location I Cluster Hospital Telephone Office Hours Hong Kong Pamela Youde Main Block Enquiry Counter I 2595 6205 East Cluster Nethersole G/F., Main Block, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Eastern Hospital Hospital I Monday to Friday 9:00a.m. to 5:00p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 1 :00 p.m. Ruttonjee Medical Records Office I 2291 1035 Hospital LG1, Hospital Main Building, Ruttonjee Hospital I Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 1 :00 p.m. 2:00p.m. to 5:30p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 12:00 noon St. John Hospital Personnel Office I 2981 9442 2/F., Out-Patients Block, St. John Hospital I Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 1 :00 p.m. 2:00p.m. to 5:00p.m. Hong Kong Queen Mary Health Information & Records Office I 2855 4175 West Cluster Hospital 2/F., Block S, Queen Mary Hospital I Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 1 :00 p.m. 2:00p.m. to 5:00p.m. Saturday 9:00a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Grantham Patient Relations Officer I 2518 2182 Hospital 1/F., Kwok Tak Seng Heart Centre, Grantham Hospital I Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00p.m. -2- Responsible Office I Location I Cluster Hospital Telephone Office Hours Kowloon Kwong Wah Medical Report Office I 3517 5216 West Cluster Hospital 3B, Administration Building, Kwong Wah Hospital I Monday to Friday 9:00 am. -

Item for Finance Committee

For discussion FCR(2015-16)3 on 17 April 2015 ITEM FOR FINANCE COMMITTEE LOAN FUND NEW HEAD – “Private Hospital Development” New Subhead – “Loan for the CUHK Medical Centre Development Project” Members are invited to approve a commitment of $4,033 million for the provision of a loan to the CUHK Medical Centre Limited, a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, for the purpose of developing a non-profit making private teaching hospital, to be named the CUHK Medical Centre. PROBLEM The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), a statutory body incorporated under the Chinese University of Hong Kong Ordinance (Cap. 1109), requires the Government’s financial support in the form of a loan to implement the CUHK Medical Centre Development Project. PROPOSAL 2. The Secretary for Food and Health recommends the creation of a new commitment of $4,033 million, and the provision by the Government to the CUHK Medical Centre Limited, a wholly-owned subsidiary of CUHK, of a loan of $4,033 million under the Loan Fund. The proposed loan is to finance the development costs of a non-profit making private teaching hospital, to be named the CUHK Medical Centre, by CUHK and is for a period of 15 years with interest-free for the first five years from the first drawdown in 2016-17 and on a floating interest rate equivalent to the interest rate of the Government’s fiscal reserves placed with the Exchange Fund from 2021 onwards. /JUSTIFICATION ….. FCR(2015-16)3 Page 2 JUSTIFICATION The Development Proposal 3. -

Faculty of Dentistry Handbook 1999

The University of Sydney Faculty of Dentistry Handbook 1999 The University's homepage tells you all about courses at Communications should be addressed to: Sydney, some careers they can lead to, and what university life The University of Sydney, NSW 2006. is like. The interactive website, with video and sound clips, Phone (02) 9351 2222 has links to the University's faculties and departments. You can explore the University of Sydney on the web at United Dental Hospital of Sydney http://www.usyd.edu.au/. Phone (02) 9351 8349, fax (02) 9211 5912 The Faculty of Dentistry web site is located at Westmead Centre for Oral Health http://www.dentistry.usyd.edu.au/. Phone (02) 9845 7192, fax (02) 9845 2893 University semester and vacation dates 1999 Last dates for withdrawal or discontinuation 1999 Academic year information (Academic Board policy and Day Date (1999) dates 1998-2002) is available at: http://www.usyd.edu.au/su/planning/policy/acad/3_0aca.html Semester 1,1999 Last day to Add a unit Friday 12 March Day Date (1999) Last day for Withdrawal Tuesday 30 March First Semester lectures begin Monday 1 March (no HECS liability, no academic penalty) Easter recess Last day to Discontinue with Friday 17 April Last day of lectures Thursday 1 April Permission (HECS liability incurred; no academic penalty) Lectures resume Monday 12 April Last day to Discontinue Friday 11 June Study vacation: 1 week beginning Monday 14 June (HECS liability incurred; result of 'Discontinued' recorded) Examinations commence Monday 21 June Semester!, 1999 First Semester -

Research Newsletter Volume 2; Issue 2

Prince of Wales Clinical School Research Newsletter Volume 2; Issue 2. November 2019 Welcome to the second where she was previously the Project Officer for the issue of the Prince of UNSW Medicine Themes. Wales Clinical School Research Newsletter for Warm regards, 2019. Professor Phil Crowe Following the first rounds Head of School of the new NHMRC Prince of Wales Clinical School Funding Scheme this year, the calendar for grants and fellowships commencing in 2021 TOW PRIZE has been updated. Most notably, the Investigator The 47th Annual Tow Coast Association Health & Grants will now open in October and close in Medical Research Early Career Awards will be November 2019. More details are available on the NHMRC website. held on Friday 29th November 2019 at the Edmund Blacket Building, Prince of Wales The affectionately named 'Randwick Sandpit' is Hospital. rapidly changing the landscape of the hospitals campus. Many of you will have been asked to Over $15,000 in prizes are typically awarded, engage with the various working groups and sub- including travel awards for winners to present their working groups being established for the Randwick work at a national or international conference. There Precinct. You may be experiening precint fatigue are six different divisions of prizes to support work however, I urge you to become involved and have by early career investigators on the Randwick your say on the future of the site and to also ask Hospitals Campus, including Ph.D. and other higher- questions, if you are unsure or feel you've been degree students and recent graduates, physicians, missed from the conversation. -

Visit and Study in the Prince of Wales Hospital

Author: Echo Zhang Study in Hong Kong: Page 1/3 Norman Bethune Medical Science Center Jilin University, Jilin Province China Visit and Study in the Prince of Wales Hospital Editor’s note: Ms. Echo Zhang was an exchange student at the Prince of Wales Hospital in 2005. Her essay also appears in Chinese. Being a common medical student in mainland, it is almost a fantastic dream to have a chance to study in hospitals in Hong Kong. But when the dream come true on me, I feel much more responsible than cheery. The responsibility to the communication of medical education, to the contact of medical students and to myself. During the 28 days’ studying life in Prince of Wales Hospital, these responsibilities pushed me everyday to observe, to discover, to experience, to accumulate and to think. The fresh things, the differences and the conflicts I confronted these days also knocked on me continuously to remind me of learning and gaining. To me, the most striking impression of medical education in HK is its completely English teaching system. Both textbooks and teaching methods are internationalized. As long as you can speak English, no matter where you are from, there’s no barrier to accept medical education here. I’ve met some exchange students from Germany and UK during my clinical attachment, and the students of Faculty of Medicine in CUHK are also required to intern for a certain period of time in other hospitals outside Hong Kong. Such internationalization and compatibility provide more chances to communicate with worldwide professionals and to receive the latest, most advanced information in medical field. -

List of Medical Social Services Units Under Social Welfare Department

List of Medical Social Services Units Under Social Welfare Department Hong Kong Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 1. Queen Mary Hospital 2255 3762 [email protected] 2255 3764 2. Wong Chuk Hang Hospital 2873 7201 [email protected] 3. Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern 2595 6262 [email protected] Hospital 4. Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern 2595 6773 [email protected] Hospital (Psychiatric Department) Kowloon Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 5. Tseung Kwan O Hospital 2208 0335 [email protected] 2208 0327 6. United Christian Hospital 3949 5178 [email protected] (Psychiatry) 7. Queen Elizabeth Hospital 3506 7021 [email protected] 3506 7027 3506 5499 3506 4021 8. Hong Kong Eye Hospital 2762 3069 [email protected] 9. Kowloon Hospital Rehabilitation 3129 7857 [email protected] Building 10. Kowloon Hospital 3129 6193 [email protected] 11. Kowloon Hospital 2768 8534 [email protected] (Psychiatric Department) 1 The New Territories Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 12. Prince of Wales Hospital 3505 2400 [email protected] 13. Shatin Hospital 3919 7521 [email protected] 14. Tai Po Hospital 2607 6304 [email protected] Sub-office Tai Po Hospital (Child and Adolescent 2689 2486 [email protected] Mental Health Centre) 15. North District Hospital 2683 7750 [email protected] 16. Tin Shui Wai Hospital 3513 5391 [email protected] 17. Castle Peak Hospital 2456 7401 [email protected] 18. Siu Lam Hospital 2456 7186 [email protected] 19. -

LC Paper No. CB(4)600/20-21(07) for Discussion on 12 March 2021

LC Paper No. CB(4)600/20-21(07) For discussion on 12 March 2021 Legislative Council Panel on Health Services Three Projects under the First Ten-year Hospital Development Plan and An Update on the First Ten-year Hospital Development Plan Purpose This paper invites Members’ comments on the following three projects under the First Ten-year Hospital Development Plan (HDP) and briefs Members on an update on the First Ten-year HDP – (a) main works for the construction of New Acute Hospital at Kai Tak Development Area at an estimated cost of $36,860.0 million in money-of-the-day (MOD) prices; (b) site formation and foundation works for the expansion of North District Hospital at an estimated cost of $2,141.0 million in MOD prices; and (c) site formation and foundation works for the expansion of Lai King Building in Princess Margaret Hospital at an estimated cost of $408.4 million in MOD prices. The total commitment sought is $39,409.4 million. Details of the above three HDP projects and the update on the First Ten-year HDP are at Enclosures 1 to 4 respectively. Background 2. In the 2016 Policy Address, the Government announced that $200 billion would be set aside for the Hospital Authority to implement the First Ten-year HDP. The First Ten-year HDP covers the redevelopment and expansion of 11 hospitals, the construction of a new acute hospital, three community health centres and one supporting services centre. Upon completion of all the projects under the First Ten-year HDP, it will provide more than 6 000 additional bed spaces, 94 additional operating theatres and increased capacity of specialist outpatient clinics and general outpatient clinics. -

Specialist Directory 2020

SPECIALIST DIRECTORY 2020 Prince of Wales Private Hospital is a leading high-level tertiary healthcare facility that specialises in acute surgery and maternity services. The Hospital is independently recognised for clinical safety and service excellence, and is renowned for achieving outstanding patient outcomes. Prince of Wales Private Hospital has a tertiary Level 3 Intensive Care Unit. CARDIOLOGY CARDIOLOGY (Cont.) CARDIOLOGY (Cont.) Dr Roger Allan Dr Simon Eggleton Dr Sean Gomes Diagnostic Procedures | Interventional Clinical and Preventative Cardiology | Diagnostic Procedures | Electrophysiology Procedures | Electrophysiology Studies | Preoperative Assessment | Studies | Implantable Electronic Devices Implantable Electronic Devices Transoesophageal Echocardiography | Eastern Heart Clinic Eastern Heart Clinic Cardiac CT Level 3, Prince of Wales Hospital Level 3, Prince of Wales Hospital Randwick Cardiology Barker Street, Randwick NSW 2031 Barker Street, Randwick NSW 2031 Level 3, 66 High Street P 02 9382 0700 F 02 9382 0799 P 02 9382 0700 F 02 9382 0799 Randwick NSW 2031 E [email protected] E [email protected] P 02 9398 2543 F 02 9399 9027 W ehc.com.au W ehc.com.au E [email protected] W randwickcardiology.com.au Dr Rahn Ilsar Dr Con Arronis Cardiac Electrophysiology Cardiology Dr Anthony Freeman Sydney Heart Rhythm Centre Bondi Cardiology Coronary Disease Assessment and Suite 12, Level 5, 1 South Street Suite 1706, Level 17, Tower 1 Westfield Prevention | Cardiac Imaging | Sports Kogarah NSW 2217 520 Oxford Street Cardiology P -

Prince of Wales Hospital

急症病人捷運隊 威爾斯親王醫院 PWH Service Accessibility Improvement Team (The Block-buster Team) Prince of Wales Hospital Prince of Wales Hospital Deputy Hospital Chief Executive Chief of Service (Oncology) (Operations) Prof Anthony Chan Tak-cheung Dr Cheung Nai-kwong (Team Leader) Chief of Service (Ophthalmology & Cluster General Manager (Nursing) Visual Sciences) Ms Becky Ho Pui-yee (Team Leader) Dr Wilson Yip Wai-kuen Deputy Hospital Chief Executive Chief of Service (Ear Nose & Throat) (Planning & Community Services) Dr Eddy Wong Wai-yeung Dr So Wing-yee Chief of Service (Department of Cluster General Manager Imaging & Interventional Radiology)) (Administrative Services) Dr Jeffrey Wong Ka-tak Ms Zenobia Shum Man-fong Chief of Service (Family Medicine) Cluster General Manager (Finance) Dr Eric Hui Ming-tung Ms Freda Lo Suk-han Chief of Service (Intensive Care Unit) Cluster General Manager (Human Prof Joynt Gavin-matthew Resources) Chief of Service (Microbiology) Mr Karson Leung Ka-sing Dr Raymond Lai Wai-man Chief of Service (Accident & Chief of Service (Haematology Emergency) Anatomical & Cellular Pathology) Dr Cheng Chi-hung Prof Margaret Ng Heung-ling Chief of Service (Medicine & Chief of Service (Chemical Pathology) Therapeutics) Prof Allen Chan Kwan-chee Dr Chow Kai-ming Cluster Service Coordinator Chief of Service (Surgery) (Pharmacy) Prof Enders Ng Kwok-wai Dr Benjamin Lee Shing-cheung Chief of Service (Obstetrics & Cluster Service Coordinator (Allied Gynaecology) Health) Dr Symphorosa Chan Shing-chee Dr Eddy Siu Hon-kit Chief of Service -

22Nd CUHK-AADO

CUHK-OLC Surgeon Education Program: The 36th AADO-OLC Comprehensive Bioskill Course on Fracture Fixation Theme: Lower Limb Trauma 1-2 December 2018 Orthopaedic Learning Centre 1/F Li Ka Shing Specialist Clinics North Wing, Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong Course Chairmen: Dr Ning Tang Consultant, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Prince of Wales Hospital Dr Kin-bong Lee Consultant, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Invited Speaker: Dr Yu-han Chee Assistant Professor & Consultant, University Orthopaedics, Hand & Reconstructive Microsurgery Cluster, National University Hospital, Singapore Faculty: Dr Esther Ching-san Chow Associate Consultant, Department of Orthopaedics & Traumatology, United Christian Hospital Dr Kwong-yin Chung Associate Consultant, Department of Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Prince of Wales Hospital Dr Ivan Ka-chun Ip Associate Consultant, Department of Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Dr Raymond Wai-kit Ng Specialist, Department of Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Prince of Wales Hospital Dr Iris Sze-ling Ngai Associate Consultant, Department of Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Dr Lung-fung Tse Consultant, Department of Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Union Hospital Dr Chi-yin Tso Associate Consultant, Department of Orthopaedics & Traumatology, Prince of Wales Hospital Dr Wan-yiu Shen Consultant, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Queen Elizabeth Hospital Dr Ronald Man-yeung Wong Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of -

Case Study: Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong in 2018, the Division Of

Case study: Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong In 2018, the Division of Cardiac Surgery at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, at the Prince of Wales Hospital (PWH), Shatin, New Territories, Hong Kong, published its 7th ‘Cardiac Surgery Report’, which reported that cardiac surgery is the safety and effective and that the outcomes are comparable to against international standards. The Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery is part of an acute regional hospital as well as the teaching hospital associated with the Chinese University of Hong Kong. It performs over 700 ultra-major cases per year and provides complete services within the specialty for a population of approximately 2.2 million people excluding paediatric cardiac surgery and transplantation. The Division provides clinical service for both cardiac and thoracic pathologies, and has developed a high quality service for the most complex of cardiac cases including multiple valvular surgeries, complex re-operative surgeries (12% of their workload) as well as routine revascularisation procedures. “Since our first report in 2007, we have moved purposefully from basic outcome analysis to comprehensive ‘international benchmarking’,” said Professor Malcolm Underwood, Chief, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery at the hospital. “We believe that presentation of our outcomes in an open and ‘risk-adjusted’ manner has become a fundamental professional responsibility. Continuous monitoring of outcomes and provision of high Quality patient care in a demonstrable fashion will always have a high priority in our Department.” When Professor Underwood first arrived in Hong Kong in 2006, there was no database collecting outcomes data on cardiac surgery procedures at PWH. Having previously worked at the Bristol Heart Institute (1999-2005) during the aftermath of the Bristol heart scandal, he was fully aware of the importance of professional accountability and responsibility cardiac surgeons, in part by publishing outcomes data on their performance. -

(16 January 2018) List of Hospitals/Clinics Under the Hospital Authority

Social Welfare Department List of Medical Social Services Units (16 January 2018) List of Hospitals/Clinics under the Hospital Authority Hong Kong Name of Hospital/Clinic Address Tel. No. Fax. No. Opening Hours 1. Queen Mary Hospital J122, 1/F, Block J, 2255 3762 2872 8565 Mon – Fri: 8:45 am – 5:15 pm Queen Mary Hospital, 2255 3764 Lunch break: 1:00 pm to 2:00 pm Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong Sat: 9:00 am – 12:00 noon 2. Wong Chuk Hang Hospital G/F, Wong Chuk Hang Hospital, 2873 7201 2554 7318 Mon – Fri: 8:45 am – 5:15 pm 2 Wong Chuk Hang Path, Lunch break: 12:30 pm to 1:30 pm Wong Chuk Hang, Hong Kong Sat: 9:00 am – 12:00 noon 3. Western Psychiatric Centre G/F, South Wing, David Trench 2517 8141 2559 9464 Mon – Fri: 8:30 am – 6:00 pm Rehabilitation Centre, Lunch break: 1:00 pm to 2:00 pm 1F High Street, Hong Kong 4. Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Room 081, 1/F, Main Block, Pamela 2595 6262 2558 6023 Mon – Fri:8:45 am – 5:15 pm Hospital Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Lunch break: 1:00 pm to 2:00 pm 3 Lok Man Road, Chai Wan, Sat: 9:00 am – 1:00 pm Hong Kong 5. Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern 7/F, East Block, Pamela Youde 2595 6773 2557 4231 Mon – Fri: 8:45 am – 5:15 pm Hospital (Psychiatric Department) Nethersole Eastern Hospital, Lunch break: 1:00 pm to 2:00 pm 3 Lok Man Road, Sat: 9:00 am – 1:00 pm Chai Wan, Hong Kong Kowloon Name of Hospital/Clinic Address Tel.