PA6317 Dissertation the Death of Pop Music Are We Amid the Silent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

3/30/2021 Tagscanner Extended Playlist File:///E:/Dropbox/Music For

3/30/2021 TagScanner Extended PlayList Total tracks number: 2175 Total tracks length: 132:57:20 Total tracks size: 17.4 GB # Artist Title Length 01 *NSync Bye Bye Bye 03:17 02 *NSync Girlfriend (Album Version) 04:13 03 *NSync It's Gonna Be Me 03:10 04 1 Giant Leap My Culture 03:36 05 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Jucxi So Confused 03:35 06 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Naila Boss It Can't Be Right 03:26 07 2Pac Feat. Elton John Ghetto Gospel 03:55 08 3 Doors Down Be Like That 04:24 09 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:54 10 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:53 11 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 03:52 12 3 Doors Down When Im Gone 04:13 13 3 Of A Kind Baby Cakes 02:32 14 3lw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 04:19 15 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 03:12 16 4 Strings (Take Me Away) Into The Night 03:08 17 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot 03:12 18 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 03:21 19 50 Cent Disco Inferno 03:33 20 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 21 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 03:57 22 50 Cent P.I.M.P. 04:15 23 50 Cent Wanksta 03:37 24 50 Cent Feat. Nate Dogg 21 Questions 03:41 25 50 Cent Ft Olivia Candy Shop 03:26 26 98 Degrees Give Me Just One Night 03:29 27 112 It's Over Now 04:22 28 112 Peaches & Cream 03:12 29 220 KID, Gracey Don’t Need Love 03:14 A R Rahman & The Pussycat Dolls Feat. -

![Power. Sir T. Browne. Attract, Vt] Attracting](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8102/power-sir-t-browne-attract-vt-attracting-848102.webp)

Power. Sir T. Browne. Attract, Vt] Attracting

power. Sir T. Browne. Attract, v. t.] Attracting; drawing; attractive. The motion of the steel to its attrahent. Glanvill. 2. (Med.) A substance which, by irritating the surface, excites action in the part to which it is applied, as a blister, an epispastic, a sinapism. trap. See Trap (for taking game).] To entrap; to insnare. [Obs.] Grafton. trapping; to array. [Obs.] Shall your horse be attrapped . more richly? Holland. page 1 / 540 handle.] Frequent handling or touching. [Obs.] Jer. Taylor. Errors . attributable to carelessness. J.D. Hooker. We attribute nothing to God that hath any repugnancy or contradiction in it. Abp. Tillotson. The merit of service is seldom attributed to the true and exact performer. Shak. But mercy is above this sceptered away; . It is an attribute to God himself. Shak. 2. Reputation. [Poetic] Shak. 3. (Paint. & Sculp.) A conventional symbol of office, character, or identity, added to any particular figure; as, a club is the attribute of Hercules. 4. (Gram.) Quality, etc., denoted by an attributive; an attributive adjunct or adjective. 2. That which is ascribed or attributed. Milton. Effected by attrition of the inward stomach. Arbuthnot. 2. The state of being worn. Johnson. 3. (Theol.) Grief for sin arising only from fear of punishment or feelings of shame. See Contrition. page 2 / 540 Wallis. Chaucer. 1. To tune or put in tune; to make melodious; to adjust, as one sound or musical instrument to another; as, to attune the voice to a harp. 2. To arrange fitly; to make accordant. Wake to energy each social aim, Attuned spontaneous to the will of Jove. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Most Requested Songs of 2009

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on nearly 2 million requests made at weddings & parties through the DJ Intelligence music request system in 2009 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 4 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 5 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 6 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 7 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 8 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 9 B-52's Love Shack 10 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 11 ABBA Dancing Queen 12 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 13 Black Eyed Peas Boom Boom Pow 14 Rihanna Don't Stop The Music 15 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 16 Outkast Hey Ya! 17 Sister Sledge We Are Family 18 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 19 Kool & The Gang Celebration 20 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 21 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 22 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 23 Lady Gaga Poker Face 24 Beatles Twist And Shout 25 James, Etta At Last 26 Black Eyed Peas Let's Get It Started 27 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 28 Jackson, Michael Thriller 29 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 30 Mraz, Jason I'm Yours 31 Commodores Brick House 32 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 33 Temptations My Girl 34 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup 35 Vanilla Ice Ice Ice Baby 36 Bee Gees Stayin' Alive 37 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 38 Village People Y.M.C.A. -

How to Break Your Band on the Internet

Slide 1 How to Break Your Band on the Internet Methods, Tools & Tips By Ian Clifford For Make It In Music Slide 2 About Ian Clifford • Worked in the music business for over 20 years • 4 years as a music lawyer • Managed songwriters & producers / artists • Owned Indie labels – Classic / Illicit • Hit records as a manager and label • Studied ‘music marketing’ at Berklee • Consultant – DTF, marketing, records & publishing • Set up ‘Make It In Music’ in 2009 to advise DIY musicians 2 Started as music lawyer Moved on to become manager of songwriters & producers – managed the team that helmed the careers of the Spice Girls. First client, Happy Clappers signed to WEA and had several European hits, inc ‘I Believe’ going top 10 in the UK. Career as a manager saw number of artists signed to major label deals covering dance music (DJ Rap (Sony) / Freeform Five (Atlantic and Universal)), indie (Chikinki (Island)) and electronica (Deadly Avenger (Sony). Labels – set up with DJ’s – legendary house music label run with Derrick Carter, Chicago. With Deadly Avenger, pioneering big beat label – Illicit. Those labels releasing one record a week and we were involved in every aspect of their recording, manufacturing, promotion, marketing and release. We also promoted gigs for the DJ’s 1 and artists in the UK and abroad as well as learning to promote to press, radio and online – ourselves and with specialist PR companies & pluggers. Biggest hit as a label was Fatman Scoop, ‘Be Faithful’ selling a million copies across Europe. Many hits as managers of writer/producers. Currently, we have returned to managing a core group of writers & producers who between them write for LadyHawke, Little Boots, Robbie Williams, Delphic & Tracey Thorn – to name a few. -

GB BONJOUR1 8/7/09 16:09 Page 1

GB BONJOUR1 8/7/09 16:09 Page 1 Teacher’s Notes September/October 2009 ISSN 0006-7121 ® BONJOUR SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2009 Page Articles Topics Teaching ideas BACKGROUND 2 ZIG ZAG Current events In pairs, get your pupils to share a few Little Boots may have won BBC’s Sound of 2009, but that doesn’t mean silly jokes, like the one on page two. that White Lies and Florence and The Can they translate one into French? Machine should despair. After all, last 4 BOUGE ! Tennis players Please go to page 2. year Adele won, but the runner up, and their injuries See worksheet 1 on illness and injuries. Duffy, went on to achieve an incredible level of success as well. And 6 CULTURE French speaking Please go to page 7. while Adele won both the Sound of DÉTECTIVE parts of the See worksheet 2 on France’s DOM-TOM, 2008 and the BRIT Critics’ Choice world other departments, and regions. award in 2008, Little Boots came in 8 STAR BBC’s Sound of Please go to page 7. second for the Critics’ Choice award, bested by Florence and The Machine. 2009, numbers See worksheet 3 on numbers. The White Lies came in third for that 10 TON MONDE Holidays Take a survey to find out which holiday award, still a strong contender. The your pupils would prefer. Then, put BBC’s Sound of … list is decided each pupils in pairs to interview each other year by just over 100 people in the in French about their holiday activities. -

Pop 2 a Second Packet for Popheads Written by Kevin Kodama Bonuses 1

Pop 2 a second packet for popheads written by Kevin Kodama Bonuses 1. One song from this album says “If they keep telling me where to go / I’ll blow my brains out to the radio”. For ten points each, [10] Name this sophomore album by Lorde. This Grammy-nominated album contains songs like “Perfect Places” and “Green Light”. ANSWER: Melodrama <Easy, 2/2> [10] Melodrama was created with the help of this prolific producer and gated reverb lover. This producer also worked on Norman Fucking Rockwell! with Lana del Rey and folklore with Taylor Swift. ANSWER: Jack Antonoff <Mid, 2/2> [10] This Melodrama track begins with documentary audio that remarks “This is my favorite tape!” and a Phil Collins drum sample. This song draws out the word “generation” after spelling the title phrase. ANSWER: “Loveless” (prompt on “Hard Feelings/Loveless”) <Hard, 2/2> 2. This artist's first solo release was an acid house track called "Dope". For ten points each, [10] Name this Kazakh producer who remixed a certain SAINt JHN song into a 2020 hit. This producer's bass effects are a constant presence in that song, which goes "You know I get too lit when I turn it on". ANSWER: Imanbek <Mid, 1/2> [10] That aforementioned song by SAINt JHN has this title and goes "Never sold a bag but look like Pablo in a photo". This is also the title of the final song in Carly Rae Jepsen's E•MO•TION Side B. ANSWER: "Roses" <Easy, 2/2> [10] After "Roses", Imanbek went on to sign with this producer's label Dharma. -

Little Boots About

LITTLE BOOTS ABOUT Making headlines and chart topping hits since she first emerged in 2008, Little Boots won the respected BBC Sound Of poll and a Brits Critics Choice nomination just a year later. Fusing massive pop hooks onto otherworldly electronic soundscapes it showed a pop star willing to experiment, and her debut album 'Hands' reached the top 5 in the UK album chart and was quickly certified Gold. Her electrifying live show gained a reputation, pushing boundaries with ground breaking instruments and synthesizers such as the Tenori-on and Laser Harp, culminating in memorable live performances at Glastonbury and Coachella to name a few. Freeing herself of the major label machine she went on to found her own label On Repeat Records and independently released various EPs and two more critically acclaimed albums - 2013’s ‘Nocturnes’ and most recently 'Working Girl’, as well as signing and developing up and coming talent. In 2017 she collaborated with the legendary Jean-Michel Jarre and co-wrote the lead single for his latest record, which received a Grammy nomination for Best Electronic Album. As a DJ her ties with the dance culture are deep and long-running. From her first legendary white label release 'Stuck On Repeat’, produced by Joe Goddard, to gracing Mixmag's cover, it's hard to think of another popstar to have garnered anywhere near as much credibility from the dance world's inner-circle. From collaborating with dance royalty Maya Jane Coles, Hercules and Love Affair and Simian Mobile Disco, to her own decorated DJ career, highlights including her live set for Mixmag Lab which has clocked up over 1.4 million views, curating one of Space’s closing We Love party in Ibiza and spinning everywhere from Glastonbury to Valentino’s latest launch at Milan Fashion Week. -

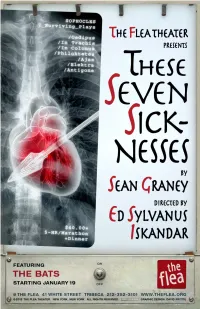

These-Seven-Sicknesses.Pdf

THE FLEA THEATER JIM SIMP S ON ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OS TROW PRODUCING DIRECTOR BETH DEM B ROW MANAGING DIRECTOR PRESENTS THE NEW YORK PREMIERE OF THESE SEVEN SICKNESSES WRITTEN BY SEAN GRANEY DIRECTED BY ED SYLVANU S IS KAN D AR FEATURING THE BAT S JULIA NOULIN -MERAT SET DESIGN CARL WIEMANN LIGHTING DESIGN LOREN SHAW COSTUME DESIGN PATRI C K METZ G ER SOUND DESIGN MI C HAEL WIE S ER FIGHT DIRECTION DAVI D DA bb ON MUSIC DIRECTION GRE G VANHORN DRAMATURG ED WAR D HERMAN , KARA KAUFMAN STAGE MANAGMENT These Seven Sicknesses was originally incubated in New York City during Lab 2 at Exit, Pursued by a Bear (EPBB), March 2011; Ed Sylvanus Iskandar, Artistic Director. THESE SEVEN SICKNESSES CAST (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE ) PROLOGUE Orderly..............................................................................................................Will Turner Nurse 1.........................................................................................................Glenna Grant New Nurse .........................................................................................Tiffany Abercrombie Nurse 2........................................................................................................Eloise Eonnet Nurse 3.............................................................................................Marie Claire Roussel Nurse 4...........................................................................................................Jenelle Chu Nurse 5.........................................................................................................Olivia -

By Song Title

Solar Entertainments Karaoke Song Listing By Song Title 3 Britney Spears 2000s 17 MK 2010s 22 Lily Allen 2000s 39 Queen 1970s 679 Fetty Wap 2010s 711 Beyonce 2010s 1973 James Blunt 2000s 1999 Prince 1980s 2002 Anne Marie 2010s #ThatPower Will.I.Am & Justin Bieber 2010s 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & The Aces 1960s 1 800 273 8255 Logic & Alessia Cara & Khalid 2010s 1 Thing Amerie 2000s 10/10 Paolo Nutini 2010s 10000 Hours Dan & Shay & Justin Bieber 2010s 18 & Life Skid Row 1980s 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 1990s 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue 2000s 20th Century Boy T Rex 1970s 21 Guns Green Day 2000s 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 2000s 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard 2000s 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 2010s 24K Magic Bruno Mars 2010s 2U David Guetta & Justin Bieber 2010s 3 AM Busted 2000s 3 Nights Dominic Fike 2010s 3 Words Cheryl Cole 2000s 30 Days Saturdays 2010s 34+35 Ariana Grande 2020s 4 44 Jay Z 2010s 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 2000s 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 2000s 5 Colours In Her Hair McFly 2000s 5,6,7,8 Steps 1990s 500 Miles (I'm Gonna Be) Proclaimers 1980s 7 Rings Ariana Grande 2010s 7 Things Miley Cyrus 2000s 7 Years Lukas Graham 2010s 74 75 Connells 1990s 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 1980s 90 Days Pink & Wrabel 2010s 99 Red Balloons Nena 1980s A Bad Dream Keane 2000s A Blossom Fell Nat King Cole 1950s A Change Would Do You Good Sheryl Crow 1990s A Cover Is Not The Book Mary Poppins Returns Soundtrack 2010s A Design For Life Manic Street Preachers 1990s A Different Beat Boyzone 1990s A Different Corner George Michael 1980s