BIA 2013) Interim Decision #3780

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birthright Citizenship and the Alien Citizen

Fordham Law Review Volume 75 Issue 5 Article 10 2007 Birthright Citizenship and the Alien Citizen Mae M. Ngai Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mae M. Ngai, Birthright Citizenship and the Alien Citizen, 75 Fordham L. Rev. 2521 (2007). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol75/iss5/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Birthright Citizenship and the Alien Citizen Cover Page Footnote Professor of History, Columbia University. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol75/iss5/10 BIRTHRIGHT CITIZENSHIP AND THE ALIEN CITIZEN Mae M. Ngai* The alien citizen is an American citizen by virtue of her birth in the United States but whose citizenship is suspect, if not denied, on account of the racialized identity of her immigrant ancestry. In this construction, the foreignness of non-European peoples is deemed unalterable, making nationality a kind of racial trait. Alienage, then, becomes a permanent condition, passed from generation to generation, adhering even to the native-born citizen. Qualifiers like "accidental" citizen,1 "presumed" citizen,2 or even "terrorist" citizen3 have been used in political and legal arguments to denigrate, compromise, and nullify the U.S. citizenship of "unassimilable" Chinese, "enemy-race" Japanese, Mexican .aA X4 -1,;- otreit." "illegal aliens," 1.1 -U1 .-O-.. -

Alien Removals and Returns: Overview and Trends

Alien Removals and Returns: Overview and Trends Updated February 3, 2015 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R43892 Alien Removals and Returns: Overview and Trends Summary The ability to remove foreign nationals (aliens) who violate U.S. immigration law is central to the immigration enforcement system. Some lawful migrants violate the terms of their admittance, and some aliens enter the United States illegally, despite U.S. immigration laws and enforcement. In 2012, there were an estimated 11.4 million resident unauthorized aliens; estimates of other removable aliens, such as lawful permanent residents who commit crimes, are elusive. With total repatriations of over 600,000 people in FY2013—including about 440,000 formal removals—the removal and return of such aliens have become important policy issues for Congress, and key issues in recent debates about immigration reform. The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) provides broad authority to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) to remove certain foreign nationals from the United States, including unauthorized aliens (i.e., foreign nationals who enter without inspection, aliens who enter with fraudulent documents, and aliens who enter legally but overstay the terms of their temporary visas) and lawfully present foreign nationals who commit certain acts that make them removable. Any foreign national found to be inadmissible or deportable under the grounds specified in the INA may be ordered removed. The INA describes procedures for making and reviewing such a determination, and specifies conditions under which certain grounds of removal may be waived. DHS officials may exercise certain forms of discretion in pursuing removal orders, and certain removable aliens may be eligible for permanent or temporary relief from removal. -

Aliens (Consolidation) Act

K:\Flygtningeministeriet\2002\bekg\510103\510103.fm 31-10-02 10:7 k03 pz Consolidation Act No. 608 of 17 July 2002 of the Danish Ministry of Refugee, Immigration and Integration Affairs Aliens (Consolidation) Act The following is a consolidation of the Aliens Act, cf. Consolidation Act No. 711 of 1 August 2001, with the amendments following from Act No. 134 of 20 March 20021), section 2 of Act No. 193 of 5 April 2002, Act No. 362 of 6 June 2002, section 1 of Act No. 365 of 6 June 2002 and Act No. 367 of 6 June 20022). Parts of the amendments following from Act No. 134 of 20 March 2002 and Act No. 367 of 6 June 2002 have not been incorporated into this Consolidation Act, as the amendments have not yet entered into force. The time of their entering into force will be determined by the Minister, cf. section 2 of the Acts. Part I EC rules only to the extent that these limitations are compatible with those rules. Aliens' entry into and stay in Denmark (4) The Minister for Refugee, Immigration and 1. Nationals of Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Integration Affairs lays down more detailed pro- Sweden may enter and stay in Denmark without visions on the implementation of the rules of the special permission. European Community on visa exemption and on 2. (1) Aliens who are nationals of a country abolition of entry and residence restrictions in which is a member of the European Community connection with the free movement of workers, or comprised by the Agreement on the European freedom of establishment and freedom to pro- Economic Area may enter and stay in Denmark vide and receive services, etc. -

20190619135814870 18-725 Barton Opp.Pdf

No. 18-725 In the Supreme Court of the United States ANDRE MARTELLO BARTON, PETITIONER v. WILLIAM P. BARR, ATTORNEY GENERAL ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION NOEL J. FRANCISCO Solicitor General Counsel of Record JOSEPH H. HUNT Assistant Attorney General DONALD E. KEENER JOHN W. BLAKELEY TIMOTHY G. HAYES Attorneys Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 [email protected] (202) 514-2217 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the stop-time rule, which governs the cal- culation of an alien’s period of continuous residence in the United States for purposes of eligibility for cancel- lation of removal, may be triggered by an offense that “renders the alien inadmissible,” 8 U.S.C. 1229b(d)(1)(B), when the alien is a lawful permanent resident who is not seeking admission. (I) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Opinions below .............................................................................. 1 Jurisdiction .................................................................................... 1 Statement ...................................................................................... 1 Argument ....................................................................................... 6 Conclusion ................................................................................... 14 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases: Ardon v. Attorney Gen. of U.S., 449 Fed. Appx. 116 (3d Cir. 2011) ...................................................................... -

Immigration Law and the Myth of Comprehensive Registration

Immigration Law and the Myth of Comprehensive Registration Nancy Morawetz†* and Natasha Fernández-Silber** This Article identifies an insidious misconception in immigration law and policy: the myth of comprehensive registration. According to this myth — proponents of which include members of the Supreme Court, federal and state officials, and commentators on both sides of the immigration federalism debate — there exists a comprehensive federal alien registration system; this scheme obligates all non-citizens in the United States to register and carry registration cards at all times, or else face criminal sanction. In truth, no such system exists today, nor has one ever existed in American history. Yet, federal agencies like U.S. Border Patrol refer to such a system to justify arrests and increase enforcement statistics; the Department of Justice points to the same mythic system to argue statutory preemption of state immigration laws (rather than confront the discriminatory purpose and effect of those laws); and, states trot it out in an attempt to turn civil immigration offenses into criminal infractions. Although this legal fiction is convenient for a variety of disparate political institutions, it is far from convenient for those who face wrongful arrest and detention based on nothing more than failure to carry proof of status. Individuals in states with aggressive “show me your papers” immigration laws or under the presence of U.S. Border Patrol are particularly at risk. In an effort to dispel this dangerous misconception, this Article reviews the history of America’s experimentation with registration laws and the † Copyright © 2014 Nancy Morawetz and Natasha Fernández-Silber. -

Alienage Jurisdiction and “Stateless” Persons and Corporations After Traffic Stream

PUTTING THE “ALIEN” BACK INTO ALIENAGE JURISDICTION: ALIENAGE JURISDICTION AND “STATELESS” PERSONS AND CORPORATIONS AFTER TRAFFIC STREAM Robert Bernheim∗ INTRODUCTION In 1994, the representatives for nine Palestinians killed by Israeli dispersion of CS gas (teargas) brought a wrongful death suit against the American manufacturer of the gas in a federal district court.1 However, Judge William L. Standish dismissed the case for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.2 The problem was that the case was based on alienage diversity jurisdiction, but the Palestinian plaintiffs were neither citizens nor subjects of any recognized state.3 This disturbing example is not an isolated jurisdictional fluke. Many companies have not been able to take advantage of U.S. federal courts because they are based out of foreign dependencies of other nations.4 Alternatively, American plaintiffs have occasionally been frustrated in their attempts to hold stateless parties accountable.5 The analysis of the law in this area is limited and unclear, and Abu-Zeineh was perfectly positioned to expose cracks in the system. Resolution of the ambiguities and contradictions in this area would streamline private international law practice, alleviate unfairness to often marginalized groups, and support the welfare and commerce of the United States. ∗ J.D. Candidate, University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of Law, 2006. I want to thank Michael Catlett, Roopali Desai, Joe Lin, Tom Raine, and Lindsay St. John for their valuable suggestions. Special thanks also go to Ann Redd and Emily Gust for understanding the madness. 1. Abu-Zeineh v. Fed. Labs., Inc., 975 F. Supp. 774 (W.D. -

19 GEO V 1928 No 58 British Nationality and Status Of

19 GEO. V.] British Nationality and Status of [1928, No. 58. 703 Aliens (in New Zealand). New Zealalltl ANALYSIS. Title. M i8cellaneous. 1. Short Title and commencement. 9. Oath of allegiance. 2. Interpretation. 10. Saving the powers of the Gem'ral Assembly to differentiate between different classeR of BRITISH NATIONALITY IN NEW ZEALAND. subjects. Adoption of Part Il of Imperial Act. 11. Records of naturalization. 3. Adoption of Part 11 of Imperial Act. 12. Penalty for false representation or statement. 4. Exercisc in New Zealand of powers conferred by Part 11 of Imperial Act. 5. Persons previously naturalized may receive STATUS OF ALIENS IN NEW ZEALAND. certificates of naturalization under this Act. Capacity to acquire Land. Derlnratory Statement as to olhe?· Provisions of l:l. Capacity of aliens to acquire Jam] in New Imperial Act8. Zealand. 6. Certain provisions of Imperial Acts declared part of law of New Zealand. REGULATIONR. Application of Act to Cook Islands and Western 14. Governor·General may mn.ke regulations for Samoa. purposes of this Act. 7. Naturalization of aliens in Cook Islands and, Western Samoa. ' R. Restricted operation of certain certificates of REPEALS. naturalization granted to residents of I 15. Repeals. Saving of existing certificates. Western Samoa. I Schedules. 1928, No. 58. AN ACT to adopt Part II of the British Nationality and Status of Title. Aliens Act, 1914 (Imperial), to make certain Provisions relating to British Nationality and the Status of Aliens in New Zealand, and also to make Special Provisions with respect to the N aturaliza tion of Persons resident in Western Samoa. -

U.S. Naturalization Policy

U.S. Naturalization Policy Updated May 3, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R43366 U.S. Naturalization Policy Summary Naturalization is the process that grants U.S. citizenship to lawful permanent residents (LPRs) who fulfill requirements established by Congress and enumerated in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). In general, U.S. immigration policy gives all LPRs the opportunity to naturalize, and doing so is voluntary. To qualify for citizenship, LPRs in most cases must have resided continuously in the United States for five years, show they possess good moral character, demonstrate English language ability, and pass a U.S. government and history examination, which is part of their naturalization interview. The INA waives some of these requirements for applicants over age 50 with 20 years of U.S. residency, those with mental or physical disabilities, and those who have served in the U.S. military. Naturalization is often viewed as a milestone for immigrants and a measure of their civic and socioeconomic integration to the United States. Naturalized immigrants gain important benefits, including the right to vote, security from deportation in most cases, access to certain public-sector jobs, and the ability to travel with a U.S. passport. U.S. citizens are also advantaged over LPRs for sponsoring relatives to immigrate to the United States. During the past three decades, the number of LPRs who submitted naturalization applications has varied over time, ranging from a low of about 207,000 applications in FY1991 to a high of 1.4 million in FY1997. In FY2020, 967,755 LPRs submitted naturalization applications. -

The California Alien Land Law and the Fourteenth Amendment

19471 The California Alien Land Law and the Fourteenth Amendment Edwin E. Ferguson* T HEPAST few years have seen a surge of, activity by California law-enforcement officers, aided by new state legislation and aug- mented appropriations, in the investigation of possible violations of the alien land law and the institution of escheat proceedings. By the summer of 1945 approximately thirty escheat actions had been begun, judgments in favor of the state had been entered in four of them, and out-of-court settlements of $100,000 and $25,000, respectively, had been effected in two others.' By the spring of 1946 some fifty actions were pending. All of these suits involved agricultural lands and were directed against persons of Japanese ancestry.2 Additional suits have since been filed.' The alien land law, first enacted in 1913, denies to aliens ineligi- ble for citizenship the right to own, lease, or otherwise enjoy land, except to the extent provided by treaty.4 Despite the manifest dis- crimination against one class of aliens and the deprivation of prop- erty rights involved, the United States Supreme Court in 1923 upheld the law, concluding that it did not violate the equal protection and due process guaranties of the Fourteenth Amendment. 5 The new wave of escheat actions has resulted in a new test of the law. Late in 1946, in an appeal from a judgment of escheat which again raised the equal protection and due process issues, the California supreme court re- affirmed the constitutionality of the law in People v. Oyama,6 relying upon the rationale provided by the 1923 decisions. -

Diversity Jurisdiction in Cases Involving Foreign Citizens and Businesses

When Is a Foreigner Diverse? Diversity Jurisdiction in Cases Involving Foreign Citizens and Businesses 66 •• THETHE FEDERALFEDERAL LAWYERLAWYER • • J JANUARYANUARY/F/EBRUARYFEBRUARY 2015 2015 BY HON. GERALDINE SOAT BROWN People, businesses, and transactions increasingly cross borders. When a dispute arises, lawyers need to know whether a federal court will have diversity jurisdiction over the ensuing lawsuit. he globalization of the American ing these jurisdictional issues by discussing the jurisdictional economy and the expansion of basis for cases filed before and after the recent change to 28 U.S.C. § 1332. The article stresses points often overlooked in Tinternational trade mean that law- determining jurisdiction over cases involving foreign citizens suits in American courts will increasingly and businesses. Finally, the article provides charts and hypo- theticals to help in determining jurisdiction. involve foreign citizens and businesses. Because practitioners as well as courts Constitutional Authority and the Diversity Statute have a duty to police the jurisdictional Article III, § 2 of the U.S. Constitution allows federal courts to adjudicate cases and controversies “between a State, or the grounding of their cases, it is important Citizens thereof, and foreign States, Citizens or Subjects.”3 To to understand the jurisdiction of federal that constitutional bedrock, Congress added a statutory layer with the Judiciary Act of 1789, narrowing federal jurisdiction to courts over disputes involving foreigners. civil actions in which a minimum sum was disputed (then only The Federal Courts Jurisdiction and Venue Clarification Act $500) and “an alien is a party, or the suit is between a citizen of 2011 (Clarification Act) amended the long-standing diversity of the State where the suit is brought, and a citizen of another jurisdiction statute, 28 U.S.C. -

Let's Get Rid of the Alien Land Law!

APABA's Mission: How Can You Help? THE FLORIDA CONSTITUTION Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Spread the word! Download the toolkit at ARTICLE 1 SECTION 2 represent 2.6% percent of the South www.apabasfla.org. Florida population, and we are proud to Basic rights.—All natural persons, female call South Florida our home. As Do the Right and male alike, are equal before the law attorneys, we recognize our special Sign up to volunteer at www.apabasfla.org. responsibility to help under-represented and have inalienable rights, among which are segments of the community; to improve Contact your elected officials: Thing – Let’s the right to enjoy and defend life and liberty, legal access to the courts; and to serve as a legal bridge between our ethnic Florida Capitol Office to pursue happiness, to be rewarded for communities and the South Florida Get Rid of the industry, and to acquire, possess and protect 404 S. Monroe Street Tallahassee, FL 32399-1100 region. Florida Senate property; except that the ownership, The mission of the Asian Pacific Sen. Lauren Book, Dist 32 Sen. Bobby Powell, Dist. 30 Alien Land Law! inheritance, disposition and possession of American Bar Association of South 202 Senate Office Bldg. 214 Senate Office Bldg Florida (APABA) is to: (850) 487-5032 (850) 487-5030 real property by aliens ineligible for • Represent and advocate the interests Sen. Oscar Braynon II, Dist 35 Sen. Kevin Rader, Dist. 29 citizenship may be regulated or prohibited by 200 Senate Office Bldg. 222 Senate Office Building of the Asian community of the South (850) 487-5035 (850) 487-5029 law. -

AILA Doc. No. 08121069. (Posted 12/10/08) Table Ofcontents

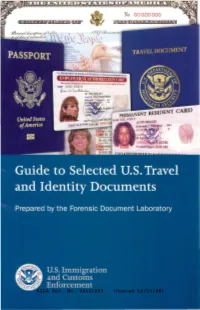

• No. 00 000 000 Sex F AILA Doc. No. 08121069. (Posted 12/10/08) Table ofContents General Information on Alien Status 3 U.S. Passports 4 Certificates of Naturalization...... ........................... ......... .............. ... 6 Residence Cards 8 Employment Authorization Cards 13 Travel Documents.......................................................................... 15 Non-ImmigrantVisas 17 I-94s 19 Immigrant Documentation 2 1 Social Security Cards 23 Ordering Information 24 AILA Doc. No. 08121069. (Posted 12/10/08) This guide is intended to assist those tasked with examining travel and employment authorization documents. It contains color photographs of the most commonly used documents, but it is not comprehensive. There are earlier valid revisions of some illustrated documents and other less common documents that are not illustrated here. Because the attachments are reproductions, the exact size and color may deviate from the original. Do not make identifications based on size and/or color alone. For any questions regarding the authenticity of the documents shown in this guide, please contact the nearest office ofu.s. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). AILA Doc. No. 08121069. (Posted 12/10/08) General Information On Alien Status In accordance with the 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, any person born in and subject to the jurisdiction of the United States is a citize~:h of the United States at birth. U.S. citizenship may also be acquired through DERIVATION from a U.S. citizen parent when children are born abroad or through NATURALIZATION after meeting the necessary residency requirements. All persons not citizens or nationals of the U.S. are aliens, who are generally classified as PERMANENT RESIDENTS (immigrants), NON IMMIGRANTS or UNDOCUMENTED ALIENS.