The Linguistic History and the Ideological Inhibitions in Foreign Language Context in the Post-Independence Algeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, ,Mter Mitwirkung Von Theodor \\'1

alter SELECTED WRITINGS VOLUME 1 1913-1926 Edited by Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England , . I Contents Copyright © 1996 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights rese rved Printed in the United States of America y l Second printing, 1997 METAPHYSICS OF "Experience" 3 This work is a transla tion of selec tions from Walter Benjamin, Gesammelte Schriften, ,mter Mitwirkung von Theodor \\'1. Adorno und Gershom Sch olem, heraltSgegeben von Rolf Tiedemann lind Hermann The Metaphysics of You Schweppenhiiuser, copyright © 1972, 1974, 1977, 1982, 1985, 1989 by Suh rkamp Verlag. "The Task of rhe Tra nslator" originally appeared in English in Wal ter Benjamin, Illuminations, ed ited by Hannah Two Poems by Friedrich Are nd t, English translation copyright © 1968 by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. "On Language as Such The Life of Students 3' and the Language of Man," "Fate and Cha racter," "Critique of Violen,?;" " Nap les," and "One-Way Street" originally appeared in English in Walter Benjamin, Reflections, English translation copyright Aphorisms on Imaginati © 1978 by Harcoun Brace Jovanovich, Inc . Published by arrangement with Harc ourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. "One-Way Street" also appeared i.n Walter Benjamin, "One-Way Street " and Other Writings (Lon A Child's View of ColOl don: NLBNerso, 1979, 1985). "Socrates" and "On the Program of the Coming Philosophy" originally appeared in English in The Philosophical Forum 15, nos. 1-2 (1983-1984). Socrates 52 Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from Inter Nationes, Bonn. -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register Summary the Clubs and Membership Figures Reflect Changes As of January 2008

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF JANUARY 2008 CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR OB MEMBERSHI P CHANGES TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR STATUS RPT DATE NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERSH 7365 026956 ORAN MEDITERRANEE 415 4 12-2007 23 0 0 0 0 0 23 7365 026957 ALGER DOYEN 415 4 12-2007 19 0 0 0 0 0 19 7365 026961 ORAN DOYEN 415 4 12-2007 17 0 0 0 0 0 17 7365 049534 ORAN EL BAHYA 415 4 01-2008 27 0 0 0 -2 -2 25 7365 050684 SIDI-BEL ABBES 415 7 12-2007 10 0 0 0 -4 -4 6 7365 056315 SIDI BEL ABBES L'ESPOIR 415 7 12-2007 8 0 0 0 0 0 8 7365 058492 ALGER MEDITERNNEE 415 4 01-2008 16 0 0 0 -1 -1 15 7365 058675 ORAN EL MURDJADJO 415 4 01-2008 21 0 0 0 -4 -4 17 7365 059183 SIDI BEL ABBES SOLEIL 415 7 01-2008 14 0 0 0 0 0 14 7365 059444 ALGER CASBAH 415 7 01-2008 9 1 0 0 0 1 10 7365 059566 ORAN BEL AIR 415 4 11-2007 13 1 0 0 -1 0 12 7365 060841 ALGER LA CITADELLE 415 4 01-2008 16 3 0 0 -1 2 18 7365 061031 ORAN PHOENIX 415 4 12-2007 16 2 0 0 0 2 18 7365 061288 ALGER EL GHALIA 415 4 11-2007 9 1 0 0 0 1 10 7365 062921 ALGER MEZGHENA 415 7 12-2007 13 0 0 0 0 0 13 7365 066380 TIZI OUZOU DJURDJURA 415 7 12-2007 15 0 0 0 0 0 15 7365 066657 TIZI OUZOU L'OLIVIER 415 7 12-2007 11 0 0 0 0 0 11 7365 066658 BLIDA EL MENARA 415 7 12-2007 8 4 0 0 -1 3 11 7365 078091 ALGER LUMIERE 415 4 01-2008 15 0 0 0 -2 -2 13 7365 082253 ALGER ZIRI 415 4 01-2008 35 3 0 1 -7 -3 32 7365 082853 SIDI BEL ABBES YASMINE 415 4 12-2007 12 0 0 0 -3 -3 9 7365 088289 SIDI BEL ABBES RAIHAN 415 7 12-2007 7 0 0 0 0 0 7 -

TITLE Kansas State Capitol Guide for Young People. Curriculum Packet for Teachers of Grades 4-7. INSTITUTION Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka.; Kansas State Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 477 746 SO 034 927 TITLE Kansas State Capitol Guide for Young People. Curriculum Packet for Teachers of Grades 4-7. INSTITUTION Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka.; Kansas State Dept. of Education, Topeka. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 27p.; Prepared by the Education and Outreach Division. Intended to supplement the "Kansas State Capitol Guide for Young People." AVAILABLE FROM Kansas State Historical Society, 6425 S.W. 6th Avenue, Topeka, KS 66615. Tel: 785-272-8681; Fax: 785-272-8682; Web site: http://www.kshs.org/. For full text: http://www.kshs.org/teachers/ classroom/capitolguide.htm. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elementary Education; Guides; *Historic Sites; *Social Studies; *State Government; *State History IDENTIFIERS Indicators; *Kansas; *State Capitals ABSTRACT This curriculum packet is about the Kansas state capitol. The packet contains six graphic organizers for students to complete. The packets are divided into three sections (with their accompanying graphic organizers): (1) "Symbolism of the Kansas Capitol Dome Statue" (Who Are the Kansa?; Finding Your Way; Say It Again); (2) "Topping the Dome: Selecting a Symbol" (What Are They Saying?; What's on Top?); and (3)"Names as Symbols" (Native American Place Names). For each section, the teacher is provided with a main point and background information for the lesson. Answers for the graphic organizers, when necessary, are provided. (BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Guide for Your\g,Dori@ Ad Astra, the statue by Richard Bergen, was placed on the Capitol Cr) dome October 2002 CD Curriculum Packet O For Teachers of Grades 4-7 © 2002 Kansas State Historical Society Prepared in consultation with the KA.NSAS Kansas State Department of Education STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY U.S. -

The Language of Fraud Cases. by Roger Shuy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015

1012 LANGUAGE, VOLUME 92, NUMBER 4 (2016) Jackendoff, Ray. 2002 . Foundations of language: Brain, meaning, grammar, evolution . Oxford: Oxford University Press. Newmeyer, Frederick J. 2005 . Possible and probable languages: A generative perspective on linguistic ty - pology . Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pinker, Steven, and Paul Bloom. 1990 . Natural language and natural selection. Behavioral and Brain Sci - ences 13.4.707–84. DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X00081061 . Progovac, Ljiljana . 1998a. Structure for coordination (part I). GLOT International 3.7.3–6. Progovac, Ljiljana . 1998b. Structure for coordination (part II). GLOT International 3.8.3–9. Department of Linguistics University of Washington–Seattle PO Box 352425 Seattle, WA 98195-2425 [[email protected]] The language of fraud cases. By Roger Shuy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015. Pp. 301. ISBN 9780190270643. $99 (Hb). Reviewed by Lawrence M. Solan, Brooklyn Law School Most of Roger Shuy’s book , The language of fraud cases , describes cases in which S was in - volved as a linguistic expert, called by parties who were accused of some kind of fraud. Written in a journalistic style to engage readers from multiple disciplines, the book is a recent addition to a series of books that S has written over the past decade, describing his experiences as an expert witness. Other books in the series describe murder cases (2014) , bribery cases (2013), sexual mis - conduct cases (2012), perjury cases (2011), and defamation cases (2010). The case narratives most often describe a hypervigilant investigator or cooperating witness in - terpreting the target’s ambiguous or incomplete statements to confirm the suspicion that the target of the investigation has indeed committed a fraud. -

Language As a Marker of Identity in Tiaret Speech Community

Linguistics and Literature Studies 7(4): 121-125, 2019 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2019.070401 Language as a Marker of Identity in Tiaret Speech Community Brahmi Mohamed*, Mahieddine Rachid, Bouhania Bachir Department of English, Faculty of Arts and Languages, University of Adrar, Algeria Copyright©2019 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract This paper explores the linguistic behavior in In his analysis of British English speakers who reside in relation to the identity of speakers who stay in their the USA, Trudgill suggests that how, the extent to which, hometown and speakers who travel from one dialect region and why accommodation to American English occurs to another. Following the methodology of sociolinguistic appears to be due to several factors such as phonological variation studies, combined with qualitative analyses, this contrast and strength of stereotyping. Adopting insights study examines two noticeable linguistic features of Tiaret from these researchers, as well as taking language compared to those acquired by speakers who moved to ideologies into consideration, this study suggests factors other dialect areas. Qualitative analyses of speakers’ social that trigger or fail to trigger accommodation by speakers identities, attitudes and language practices match migrating to a new dialect area. quantitative analyses of patterns of phonological variation. Previous sociolinguistic research has detailed how The study finds that the migrant groups do make changes historical, political and sociolinguistic factors have in their linguistic production due to their continuous influenced issues of language, identity, and conflicts in exposure to a new dialect. -

NAF SHUTTLE NEWSLETTER Week 03|2017

NAF SHUTTLE NEWSLETTER Week 03|2017 Marseilles, January 19th 2017 Newsletter NAF France week 34 NEWSLETTER NAF SHUTTLE WEEK 03 MARSEILLES, JANUARY 19 TH Chers Clients, La Ligne SSL MED est heureuse de vous faire parvenir sa Gazette hebdomadaire de la semaine 03. Vous trouverez ci-après les horaires et rotations de nos services hebdomadaires sur le Maghreb au départ de Marseille sur l’Algérie, la Tunisie et le Maroc. Cordialement, Short Sea Lines MED Dear Customer, SSL MED line is pleased to send you its newsletter, week 03 You’ll find out the schedule and rotations of our weekly services calling Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco from port of loading Marseilles. Best regards, Short Sea Lines MED NEWSLETTER NAF SHUTTLE WEEK 03 MARSEILLES, JANUARY 19TH Dear Customers, Chers Clients, Thanks to note closings as below: Nous vous remercions de bien vouloir respecter les clôtures ci-dessous Clôture VGM : Vendredi 12h VGM : Friday 12h Clôture BAS : Vendredi 14h Customs: Friday 14h Pour les arrivées par train , merci de bien vouloir créer vos AMQ avec For containers arriving by rail, and to limit impact of late arrivals, please do reconnaissance et BAET Implicite afin de limiter l’impact de retards éventuels. your customs formalities by anticipation. Only theses bookings will be Les cases AP+ « arriv tpt » seront cochées pour vous permettre de réaliser ces opérations. Seuls ces dossiers pourront être maintenus sur liste. maintained on loading list. Pour raison opérationnelle , nous ne pourrons pas étendre les clôtures au-delà For operational reasons, -

International Conference on the Black Arts Movement in the United States and Algeria November 18-19, 2019

Session Six: 11.10-12.10 (Room 35) Emily Jane O’Dell (Yale Law School-Yale University- People’s Democratic Republic of USA), Associate Professor at Sichuan University- Algeria Frantz Fanon: Algeria’s Adoptive Son Pittsburgh Institute Excavating Memories of the 1969 Pan-African Festival: Ministry of Higher Education and Moderator: Nadjiba Bouallegue (University of 08 Mai The Impact of Algeria on Theatre Artists§Writers Scientific Research 1945 -Guelma-Algeria) Mohammed Senoussi (University of M’sila-Algeria), Abdelhamid Ibn Badis University Stéphanie Melyon-Reinette (Pointe-à-Pitre-Réunion) Displacement, Identity and the Syndrome of Hybridity in - Mostaganem Faculty of Foreign Languages Algiers, 1969, The Poetic Mecca: Amiri Baraka, Frantz Chimamanda gozi Adichie’s The Thing Around Your Neck Fanon, Sonny Rupaire& The Revolutionary Culture Hana Bougherira, (University of Skikda-Algeria), Department of English Mira Hafsi (Mohamed Lamine Debaghine University- From “Flaneur” to a “Stalker”: Reconstructing Identity Sétif-Algeria), Frantz Fanon and the Black Arts in Toni Morrison’s God Help the Child Movement: Some Reflections through Drama Discussion: 12.10-12.20 Oussama Mahboub (University of Sousse-Tunisia), The 1960's Legacy of Black Acculturation between Adoption 12.20-1.20: Lunch and Resistance: Liberal vs. Conservative Moral 1.20-2: Discussion and Prospects (Amphi G) Implications in a Comparative Perspective 2-2.30: Closing Ceremony Discussion: 12-12.20 2.30: Sightseeing International Conference Session Seven: 11.10-12-10 (Room 33) On African-Americans and the Race Question “The fact that I had never seen the Algerian The Black Arts Movement Moderator: Michael A. Antonucci, (Keene State College- Casbah was of no more relevance before this Keene-New Hampshire) unanswerable panorama than the fact that the Mohamed Ben Ali Chaker (University of Skikda- in the United States Algeria) Algerians had never seen Harlem. -

A Historical and Phonetic Study of Negro Dialect. T

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1937 A Historical and Phonetic Study of Negro Dialect. T. Earl Pardoe Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pardoe, T. Earl, "A Historical and Phonetic Study of Negro Dialect." (1937). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7790. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7790 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Historioal and phonetic Study of Negro Dialect* A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Dootor of Philosophy in Louisiana State University* By T. Earl pardoe 1937 UMI Number: DP69168 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dissertation Publishing UMI DP69168 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProOuest ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. -

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 1 of 6

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 1 of 6 Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Home > Research Program > Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) respond to focused Requests for Information that are submitted to the Research Directorate in the course of the refugee protection determination process. The database contains a seven- year archive of English and French RIRs. Earlier RIRs may be found on the UNHCR's Refworld website. Please note that some RIRs have attachments which are not electronically accessible. To obtain a PDF copy of an RIR attachment, please email the Knowledge and Information Management Unit. 29 November 2013 DZA104676.FE Algeria: Forced marriages, including state protection and resources provided to women who try to avoid a marriage imposed on them; amendments made to the Family Code in 2005 (2011-November 2013) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa 1. Forced Marriages According to Voyage.gc.ca, the Government of Canada site that provides information to Canadians travelling or living abroad (Canada 27 June 2013), [translation] "forced marriages have occurred" in Algeria (ibid. 22 Mar. 2013). According to the French daily newspaper Le Figaro, the prevalence of forced marriages in countries of the Maghreb is difficult to assess (30 Nov. 2012). BALSAM, the national network of call centres for victims of violence against women in Algeria, which was founded in 2009 and had 15 call centres throughout Algeria as of 2012, states in its fourth report, published in May 2012, that since the network was implemented, of the 828 women who have contacted the call centres, 12 were victims of forced marriage and 18 were victims of attempted forced marriage (BALSAM May 2012, 4, 7, 27). -

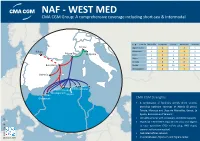

NAF - WEST MED CMA CGM Group: a Comprehensive Coverage Including Short-Sea & Intermodal

NAF - WEST MED CMA CGM Group: A comprehensive coverage including short-sea & Intermodal To From Marseilles La Spezia Genoa Barcelona Valencia Genoa Algiers ODCY 2 4 5 4 5 Bilbao Ghazaouet 2 4 5 4 5 Marseilles La Spezia Oran 2 4 5 4 5 Bejaia 6 8 9 8 9 Annaba 6 8 9 8 9 Barcelona Skikda 7 9 10 9 10 Mostaganem 2 4 5 4 5 Valencia Tunis Skikda Annaba Algiers Rouiba Mostaganem Oran Bejaia Ghazaouet CMA CGM Strengths • A combination of fixed-day weekly direct services providing optimum coverage of Algeria (8 ports), Tunisia, Morocco and Libya via Marseilles, Genoa, La Spezia, Barcelona and Valencia • Versatile services with containers and RORO capacity • Owned ALTERCO ODCY dry port in Rouiba, near Algiers to ease operations (150 reefers plug, IMO depot, scanner, railway connection) • Dedicated offices network www.cma-cgm.com October 2014 • Choice between Algiers dry and Algiers center NAF - WEST MED CMA CGM Group: A comprehensive coverage including short-sea & Intermodal Trieste Venice Genoa Ravenna CMA CGM Contacts Fos sur Mer La Spezia Ancona Livorno General Mailbox Vigo Civitavecchia [email protected] Barcelona Leixoes Naples Salerno Valencia Lisbon Gioia Tauro Bizerte Trapani Skikda Catania Algeciras Algiers Annaba Tunis Bejaia Djen Djen MALTA Oran Sfax TANGIER MED Ghazaouet Casablanca TUNISIA Tripoli Misurata Al Khoms Benghazi Agadir CMA CGM Strengths MOROCCO ALGERIA LIBYA • 9 weekly departures from Marseilles to NAF destinations • Two CMA CGM dedicated hubs: Malta and Tangier Med • Owned and dedicated feeder network from Malta ensuring weekly connections to 18 ports in the whole North Africa • Shuttle services deployed from Tangier Med to Oran, Ghazaouet, Tangier and Casablanca www.cma-cgm.com October 2014. -

On Petri Net Models of Infinite State Supervisors Where L(G) = {Wlw~~*And6*(W,G,)~Q}

274 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON AUTOMATIC CONTROL, VOL. 37, NO. 2, FEBRUARY 1992 On Petri Net Models of Infinite State Supervisors where L(G) = {wlw~~*and6*(w,g,)~Q}. R. S. Sreenivas and B. H. Krogh Given a language L G X* we use the symbol zto denote its prefix Abstract-We consider a class of supervisory control problems that closure. require infinite state supervisors and introduce Petri nets with inhibitor To control a DES we assume the set C is partitioned into two sets arcs (PN's) to model the supervisors. We compare this PN-based ap- C, and X,, where C, is the set of events that can be disabled. We proach to supervisory control to automata-based approaches. The pri- mary advantage of a PN-based supervisory controller is that a PN-based let r denote the set of control patterns, where controller provides a finite representation of an infinite state supervisor. I'={yIy:X+{O,l}andy(a)=l foreachuEC,}. For verification, implementation, and testing reasons, a finite PN-based representation of aninfinite state supervisor is preferred over an au- An event u E C is said to be enabled by y when y( u j = 1, and is tomata-basedsupervisor. We show that thismodeling advantage is disabled otherwise. accompanied by a decision disadvantage, in that in general the controlla- bility of a language that can be generated by the closed-loop system is A supervisor 0 is asystem that changes the controlpattern undecidable. dynamically.An automata-based supervisor 0 is apair (S,+), I. INTRODUCTION where S = (X,C, f , x,) is an automaton with a (possibly infinite) state set X, input alphabet C, partial transition function E: X X C Supervisory control of discrete-event systems (DES'S) was intro- -+ X, initial state x,, and 6:X -+ r. -

Burning the Veil: the Algerian War and the 'Emancipation' of Muslim

3 Unveiling: the ‘revolutionary journées’ of 13 May 1958 Throughout the period from early 1956 to early 1958 putschist forces had been gathering strength both within the army and among right- wing settler organisations and these eventually coalesced on 13 May 1958 when crowds gathered in the Forum and stormed the General Government buildings. The military rapidly used the crisis to effect a bloodless coup and to install a temporary ‘revolutionary’ authority headed by a Committee of Public Safety (Comité de salut public or CSP) under Generals Massu and Salan. There then followed a tense stand- off between the army in Algeria and the new Paris government headed by Pierre Pfl imlin, a three-week period during which civil war was a real possibility, until de Gaulle agreed to assume, once again, the role of ‘saviour of the nation’, and was voted into power by the National Assembly on 1 June.1 ‘13 May’ was one of the great turning points in modern French history, not only because it marked a key stage in the Algerian War, but more signifi cantly the collapse of the Fourth Republic, de Gaulle’s return to power, and the beginnings of the new constitutional regime of the Fifth Republic. The planning of the coup and its implementation was extraordi- narily complex – the Bromberger brothers in Les 13 Complots du 13 mai counted thirteen strands2 – but basically two antagonistic politi- cal formations reached agreement to rally to the call for de Gaulle’s return to power. On the one hand there was a secret plot by Gaullists, most notably Michel Debré (soon to become Prime Minister), Jacques Soustelle, Léon Delbecque and Jacques Chaban-Delmas (acting Minister of Defence), to engineer the return of the General so as to resolve the political crisis of the ‘system’, the dead hand of the party system of the Fourth Republic, which they viewed as destroying the grandeur of France.