John Copcot, John Whitgift, and Mark Frank: ‘Right Cause and Faithful Obedience’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hay Any Work for Cooper 1 ______

MARPRELATE TRACTS: HAY ANY WORK FOR COOPER 1 ________________________________________________________________________________ Hay Any Work For Cooper.1 Or a brief pistle directed by way of an hublication2 to the reverend bishops, counselling them if they will needs be barrelled up3 for fear of smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state, that they would use the advice of reverend Martin for the providing of their cooper. Because the reverend T.C.4 (by which mystical5 letters is understood either the bouncing parson of East Meon,6 or Tom Cook's chaplain)7 hath showed himself in his late Admonition To The People Of England to be an unskilful and beceitful8 tub-trimmer.9 Wherein worthy Martin quits himself like a man, I warrant you, in the modest defence of his self and his learned pistles, and makes the Cooper's hoops10 to fly off and the bishops' tubs11 to leak out of all cry.12 Penned and compiled by Martin the metropolitan. Printed in Europe13 not far from some of the bouncing priests. 1 Cooper: A craftsman who makes and repairs wooden vessels formed of staves and hoops, as casks, buckets, tubs. (OED, p.421) The London street cry ‘Hay any work for cooper’ provided Martin with a pun on Thomas Cooper's surname, which Martin expands on in the next two paragraphs with references to hubs’, ‘barrelling up’, ‘tub-trimmer’, ‘hoops’, ‘leaking tubs’, etc. 2 Hub: The central solid part of a wheel; the nave. (OED, p.993) 3 A commodity commonly ‘barrelled-up’ in Elizabethan England was herring, which probably explains Martin's reference to ‘smelling in the nostrils of her Majesty and the state’. -

The Quest for the Historical Hooker by JOHN Booty T Is Questionable to What Degree the Historian Or Biographer Can I Recover and Represent a Person out of the Past

The Quest for the Historical Hooker BY JOHN BooTY T is questionable to what degree the historian or biographer can I recover and represent a person out of the past. The task may be one of great difficulty when there is a wealth of material, as is true with regard to John Henry Newman. But the task may be infinitely more difficult where there is a scarcity of evidence, as is true with regard to William Shakespeare. In the quest for the historical Hooker we encounter a moderate amount of material, but we are also left with gaps and, as we now realize, we are confronted by some conflicting evidence, requiring the use of careful judgment. We begin with certain indisputable facts concerning Richard Hooker's life, facts which can be verified by reference to documents which the historian can examine and rely upon. 1 Hooker was born in 1554 at Heavitree in Devonshire of parents who were prominent in their locality but by no means wealthy. With the assistance of an uncle, the young Hooker was educated first at a grammar school in Exeter and then, under the patronage of John Jewel, Bishop of Salisbury, entered Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Subsequently he became an instructor in the University, was made a fellow of his college and was ordained to the ministry of the Church of England. There he remained, delivering the Hebrew lecture from 1579 until he departed from Oxford in 1584. Three facts concerning his time at the University are worth noting. The first is that he became the tutor of George Cranmer, whose father was a nephew of the famous Archbishop, and of Edwin Sandys, son of the Archbishop of York who became Hooker's patron after the death of Jewel in 1571. -

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Apostolic Succession of the Right Rev. James Michael St. George

The Apostolic Succession of The Right Rev. James Michael St. George © Copyright 2014-2015, The International Old Catholic Churches, Inc. 1 Table of Contents Certificates ....................................................................................................................................................4 ......................................................................................................................................................................5 Photos ...........................................................................................................................................................6 Lines of Succession........................................................................................................................................7 Succession from the Chaldean Catholic Church .......................................................................................7 Succession from the Syrian-Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch..............................................................10 The Coptic Orthodox Succession ............................................................................................................16 Succession from the Russian Orthodox Church......................................................................................20 Succession from the Melkite-Greek Patriarchate of Antioch and all East..............................................27 Duarte Costa Succession – Roman Catholic Succession .........................................................................34 -

Archbishop of Canterbury, and One of the Things This Meant Was That Fruit Orchards Would Be Established for the Monasteries

THE ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY And yet — in fact you need only draw a single thread at any point you choose out of the fabric of life and the run will make a pathway across the whole, and down that wider pathway each of the other threads will become successively visible, one by one. — Heimito von Doderer, DIE DÂIMONEN “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Archbishops of Canterb HDT WHAT? INDEX ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY 597 CE Christianity was established among the Anglo-Saxons in Kent by Augustine (this Roman import to England was of course not the Aurelius Augustinus of Hippo in Africa who had been in the ground already for some seven generations — and therefore he is referred to sometimes as “St. Augustine the Less”), who in this year became the 1st Archbishop of Canterbury, and one of the things this meant was that fruit orchards would be established for the monasteries. Despite repeated Viking attacks many of these survived. The monastery at Ely (Cambridgeshire) would be particularly famous for its orchards and vineyards. DO I HAVE YOUR ATTENTION? GOOD. Archbishops of Canterbury “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY ARCHBISHOPS OF CANTERBURY 604 CE May 26, 604: Augustine died (this Roman import to England was of course not the Aurelius Augustinus of Hippo in Africa who had been in the ground already for some seven generations — and therefore he is referred to sometimes as “St. Augustine the Less”), and Laurentius succeeded him as Archbishop of Canterbury. -

Page Is of an - Unk Nown Type ; It Is a Silver Plated Piece of the Emperor

C O N T E N T S . PAG E INTRODUCTORY P I — G CHA TER . EOLOGY II — C N . PREHISTORI CROYDO — N IN M III . CROYDO THE TI E THE RoMANs IV — S X N N . A O CROYDO V — THE OLD CHURCH . VI — . PARISH REGISTER VIL— D OMESDAY BOOK V — F N U C III . SITE O CROYDO CH R H PALACE 7 1 - 74 IX —THE A C P C P C . R HIE IS O AL PALA E AT CROYDON X — L OF M N . ORDS THE A OR XL— M ANORIAL XII - . ANCIENT DESCRIPTION AND CHRONOLOGY X - T P III . PAST O OGRAPHY XIV — M C N U . IS ELLA EO S XV — M N D . ODER EVELOPMENT INTRODUOTORY. HAVING lived for many years amid the lovely scenery of Cr n and n n n n r oydo , i quired co cer i g the histo y of its a a Old hurch and an a n n an P l ce, C , M ors, besides h vi g bee eye-witness of the n umerous changes that have taken a in r n r r pl ce here ece t times , it has occur ed to me to w ite a short topographical and historical a ccount of this parish , as n a n and such a book , without clashi g with more le r ed a ra r ma n n ra el bo te t eatises , y serve to co vey to the ge e l reader some trustworthy information respecting the locality ; and this I have endeavoured to a ccomplish in n a the followi g p ges . -

The Quest for the Historical Hooker Churchman 80/3 1966

The Quest for the Historical Hooker Churchman 80/3 1966 John Booty It is questionable to what degree the historian or biographer can recover and represent a person out of the past. The task may be one of great difficulty when there is a wealth of material, as is true with regard to John Henry Newman. But the task may be infinitely more difficult where there is a scarcity of evidence, as is true with regard to William Shakespeare. In the quest for the historical Hooker we encounter a moderate amount of material, but we are also left with gaps and, as we now realize, we are confronted by some conflicting evidence, requiring the use of careful judgment. We begin with certain indisputable facts concerning Richard Hooker’s life, facts which can be verified by reference to documents which the historian can examine and rely upon.1 Hooker was born in 1554 at Heavitree in Devonshire of parents who were prominent in their locality but by no means wealthy. With the assistance of an uncle, the young Hooker was educated first at a grammar school in Exeter and then, under the patronage of John Jewel, Bishop of Salisbury, entered Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Subsequently he became an instructor in the University, was made a fellow of his college and was ordained to the ministry of the Church of England. There he remained, delivering the Hebrew lecture from 1579 until he departed from Oxford in 1584. Three facts concerning his time at the University are worth noting. The first is that he became the tutor of George Cranmer, whose father was a nephew of the famous Archbishop, and of Edwin Sandys, son of the Archbishop of York who became Hooker’s patron after the death of Jewel in 1571. -

1052 to the Present Day

Lambeth Palace Library Research Guide Biographical Sources for Archbishops of Canterbury from 1052 to the Present Day 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 2 Abbreviations Used ....................................................................................................... 4 3 Archbishops of Canterbury 1052- .................................................................................. 5 Stigand (1052-70) .............................................................................................................. 5 Lanfranc (1070-89) ............................................................................................................ 5 Anselm (1093-1109) .......................................................................................................... 5 Ralph d’Escures (1114-22) ................................................................................................ 5 William de Corbeil (1123-36) ............................................................................................. 5 Theobold of Bec (1139-61) ................................................................................................ 5 Thomas Becket (1162-70) ................................................................................................. 6 Richard of Dover (1174-84) ............................................................................................... 6 Baldwin (1184-90) ............................................................................................................ -

Apostolic Succession

Apostolic Succession Episcopal Seal of the Most Rev. Richard A. Kalbfleisch, STL, DD, NOSF Through the Catholic Apostolic Church of Brazil (Igreja Catolica Apostolica Brasileira) Old Catholic Church of Utrecht Russian Orthodox Church The Church of England & The Episcopal Church in the USA Catholic Apostolic Church of Brazil Archbishop Carlos Duarte Costa, ordained a priest within The Church of Rome on 1 April 1911, was consecrated to be the Roman Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu, Brazil, on 8 December 1924. His public statements on the treatment of the poor in Brazil (by both the civil government and the Roman Church) resulted in his removal as Diocesan Bishop of Botucatu. Bishop Duarte Costa was subsequently named Titular Bishop of Maura by Pope Pius XII (Eugenio Cardinal Pacelli, Vatican Secretary of State until 1939 under Pope Pius XI). Archbishop Duarte Costa's criticisms of the Vatican, particularly the policy toward Nazi Germany, were not well received. He was formerly separated from the Church of Rome on 6 July 1945 after his strong and repeated public denunciations of the Vatican Secretariat of State for granting Vatican Passports to some very high ranking Nazis. Some of the most notorious Nazi war criminals (e.g., Adolf Eichmann and Dr. Josef Mengele, the "Angel of Death,") escaped trial after World War II using Vatican Passports to flee to South America. The government of Brazil also came under the Bishop's criticism for collaborating with the Vatican on these passports. Bishop Duarte Costa espoused what would be considered today as a rather liberal position on divorce, challenged mandatory celibacy for clergy, and publicly condemned the perceived abuses of papal power (especially the concept of Papal Infallibility, which he considered misguided and false). -

Prominent Elizabethans. P.1: Church; P.2: Law Officers

Prominent Elizabethans. p.1: Church; p.2: Law Officers. p.3: Miscellaneous Officers of State. p.5: Royal Household Officers. p.7: Privy Councillors. p.9: Peerages. p.11: Knights of the Garter and Garter ceremonies. p.18: Knights: chronological list; p.22: alphabetical list. p.26: Knights: miscellaneous references; Knights of St Michael. p.27-162: Prominent Elizabethans. Church: Archbishops, two Bishops, four Deans. Dates of confirmation/consecration. Archbishop of Canterbury. 1556: Reginald Pole, Archbishop and Cardinal; died 1558 Nov 17. Vacant 1558-1559 December. 1559 Dec 17: Matthew Parker; died 1575 May 17. 1576 Feb 15: Edmund Grindal; died 1583 July 6. 1583 Sept 23: John Whitgift; died 1604. Archbishop of York. 1555: Nicholas Heath; deprived 1559 July 5. 1560 Aug 8: William May elected; died the same day. 1561 Feb 25: Thomas Young; died 1568 June 26. 1570 May 22: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1576. 1577 March 8: Edwin Sandys; died 1588 July 10. 1589 Feb 19: John Piers; died 1594 Sept 28. 1595 March 24: Matthew Hutton; died 1606. Bishop of London. 1553: Edmund Bonner; deprived 1559 May 29; died in prison 1569. 1559 Dec 21: Edmund Grindal; became Archbishop of York 1570. 1570 July 13: Edwin Sandys; became Archbishop of York 1577. 1577 March 24: John Aylmer; died 1594 June 5. 1595 Jan 10: Richard Fletcher; died 1596 June 15. 1597 May 8: Richard Bancroft; became Archbishop of Canterbury 1604. Bishop of Durham. 1530: Cuthbert Tunstall; resigned 1559 Sept 28; died Nov 18. 1561 March 2: James Pilkington; died 1576 Jan 23. 1577 May 9: Richard Barnes; died 1587 Aug 24. -

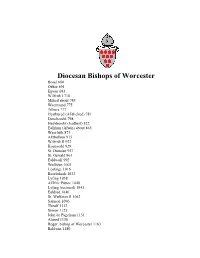

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester

Diocesan Bishops of Worcester Bosel 680 Oftfor 691 Egwin 693 Wilfrith I 718 Milred about 743 Waermund 775 Tilhere 777 Heathured (AEthelred) 781 Denebeorht 798 Heahbeorht (Eadbert) 822 Ealhhun (Alwin) about 845 Waerfrith 873 AEthelhun 915 Wilfrith II 922 Koenwald 929 St. Dunstan 957 St. Oswald 961 Ealdwulf 992 Wulfstan 1003 Leofsige 1016 Beorhtheah 1033 Lyfing 1038 AElfric Puttoc 1040 Lyfing (restored) 1041 Ealdred 1046 St. Wulfstan II 1062 Samson 1096 Theulf 1113 Simon 1125 John de Pageham 1151 Alured 1158 Roger, bishop of Worcester 1163 Baldwin 1180 William de Narhale 1185 Robert Fitz-Ralph 1191 Henry de Soilli 1193 John de Constantiis 1195 Mauger of Worcester 1198 Walter de Grey 1214 Silvester de Evesham 1216 William de Blois 1218 Walter de Cantilupe 1237 Nicholas of Ely 1266 Godfrey de Giffard 1268 William de Gainsborough 1301 Walter Reynolds 1307 Walter de Maydenston 1313 Thomas Cobham 1317 Adam de Orlton 1327 Simon de Montecute 1333 Thomas Hemenhale 1337 Wolstan de Braunsford 1339 John de Thoresby 1349 Reginald Brian 1352 John Barnet 1362 William Wittlesey 1363 William Lynn 1368 Henry Wakefield 1375 Tideman de Winchcomb 1394 Richard Clifford 1401 Thomas Peverell 1407 Philip Morgan 1419 Thomas Poulton 1425 Thomas Bourchier 1434 John Carpenter 1443 John Alcock 1476-1486 Robert Morton 1486-1497 Giovanni De Gigli 1497-1498 Silvestro De Gigli 1498-1521 Geronimo De Ghinucci 1523-1533 Hugh Latimer resigned title 1535-1539 John Bell 1539-1543 Nicholas Heath 1543-1551 John Hooper deprived of title 1552-1554 Nicholas Heath restored to title