The Biological Function and Clinical Significance of STIL in Osteosarcoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Diagnosis in First Or Second Trimester Pregnancy Loss Using Exome Sequencing: a Systematic Review of Human Essential Genes

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2019) 36:1539–1548 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-019-01499-6 REVIEW Genetic diagnosis in first or second trimester pregnancy loss using exome sequencing: a systematic review of human essential genes Sarah M. Robbins1,2 & Matthew A. Thimm3 & David Valle1 & Angie C. Jelin4 Received: 18 December 2018 /Accepted: 29 May 2019 /Published online: 4 July 2019 # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Purpose Non-aneuploid recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) affects approximately 100,000 pregnancies worldwide annually. Exome sequencing (ES) may help uncover the genetic etiology of RPL and, more generally, pregnancy loss as a whole. Previous studies have attempted to predict the genes that, when disrupted, may cause human embryonic lethality. However, predictions by these early studies rarely point to the same genes. Case reports of pathogenic variants identified in RPL cases offer another clue. We evaluated known genetic etiologies of RPL identified by ES. Methods We gathered primary research articles from PubMed and Embase involving case reports of RPL reporting variants identified by ES. Two authors independently reviewed all articles for eligibility and extracted data based on predetermined criteria. Preliminary and amended analysis isolated 380 articles; 15 met all inclusion criteria. Results These 15 articles described 74 families with 279 reported RPLs with 34 candidate pathogenic variants in 19 genes (NOP14, FOXP3, APAF1, CASP9, CHRNA1, NLRP5, MMP10, FGA, FLT1, EPAS1, IDO2, STIL, DYNC2H1, IFT122, PA DI6, CAPS, MUSK, NLRP2, NLRP7) and 26 variants of unknown significance in 25 genes. These genes cluster in four essential pathways: (1) gene expression, (2) embryonic development, (3) mitosis and cell cycle progression, and (4) inflammation and immunity. -

Identification of Common Key Genes in Breast, Lung and Prostate Cancer and Exploration of Their Heterogeneous Expression

1680 ONCOLOGY LETTERS 15: 1680-1690, 2018 Identification of common key genes in breast, lung and prostate cancer and exploration of their heterogeneous expression RICHA K. MAKHIJANI1, SHITAL A. RAUT1 and HEMANT J. PUROHIT2 1Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Visvesvaraya National Institute of Technology, Nagpur, Maharashtra 440010; 2Environmental Genomics Division, National Environmental Engineering Research Institute, Nagpur, Maharashtra 440020, India Received March 8, 2017; Accepted October 20, 2017 DOI: 10.3892/ol.2017.7508 Abstract. Cancer is one of the leading causes of mortality cancer and may be used as biomarkers for the development of worldwide, and in particular, breast cancer in women, prostate novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. cancer in men, and lung cancer in both women and men. The present study aimed to identify a common set of genes which Introduction may serve as indicators of important molecular and cellular processes in breast, prostate and lung cancer. Six microarray The highest rates of cancer-related mortality are associated gene expression profile datasets [GSE45827, GSE48984, with breast, prostate and lung cancer, as reported by the World GSE19804, GSE10072, GSE55945 and GSE26910 (two Health Organization (1), the World Cancer Report (2) and datasets for each cancer)] and one RNA-Seq expression dataset Cancer facts and figures (3) A plethora of cancer microarray (GSE62944 including all three cancer types), were downloaded and RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) studies are publicly avail- from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. Differentially able in databases, including the Gene Expression Omnibus expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in each individual (GEO) (4), Array Express (5) and The Cancer Genome Atlas cancer type using the LIMMA statistical package in R, and (TCGA; http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). -

Dissertation

Aus dem Institut für Medizinische Genetik und Humangenetik der Medizinischen Fakultät Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin DISSERTATION Molecular genetic and cytogenetic analyses of autosomal recessive primary microcephaly (MCPH): Mouse model, new locus and novel mutations zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor of Philosophy in Medical Neurosciences (PhD in Medical Neurosciences) vorgelegt der Medizinischen Fakultät Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin Mahdi Ghani-Kakhki aus dem IRAN Gutachter: 1) Prof. Dr. K. Sperling 2) Prof. Dr. med. E. Schröck 3) Prof. Dr. med. E. Schwinger Datum der Promotion: 01.02.2013 Table of Contents Zusammenfassung ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Abstract ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Aims of the PhD thesis .................................................................................................................................. 6 Hypotheses .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Methods...................................................................................................................................................... -

Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly Primary Hereditary: an Overview

brain sciences Review Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly Primary Hereditary: An Overview Nikistratos Siskos † , Electra Stylianopoulou †, Georgios Skavdis and Maria E. Grigoriou * Department of Molecular Biology & Genetics, Democritus University of Thrace, 68100 Alexandroupolis, Greece; [email protected] (N.S.); [email protected] (E.S.); [email protected] (G.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] † Equal contribution. Abstract: MicroCephaly Primary Hereditary (MCPH) is a rare congenital neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by a significant reduction of the occipitofrontal head circumference and mild to moderate mental disability. Patients have small brains, though with overall normal architecture; therefore, studying MCPH can reveal not only the pathological mechanisms leading to this condition, but also the mechanisms operating during normal development. MCPH is genetically heterogeneous, with 27 genes listed so far in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database. In this review, we discuss the role of MCPH proteins and delineate the molecular mechanisms and common pathways in which they participate. Keywords: microcephaly; MCPH; MCPH1–MCPH27; molecular genetics; cell cycle 1. Introduction Citation: Siskos, N.; Stylianopoulou, Microcephaly, from the Greek word µικρoκεϕαλi´α (mikrokephalia), meaning small E.; Skavdis, G.; Grigoriou, M.E. head, is a term used to describe a cranium with reduction of the occipitofrontal head circum- Molecular Genetics of Microcephaly ference equal, or more that teo standard deviations -

Proteomic Expression Profile in Human Temporomandibular Joint

diagnostics Article Proteomic Expression Profile in Human Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction Andrea Duarte Doetzer 1,*, Roberto Hirochi Herai 1 , Marília Afonso Rabelo Buzalaf 2 and Paula Cristina Trevilatto 1 1 Graduate Program in Health Sciences, School of Medicine, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR), Curitiba 80215-901, Brazil; [email protected] (R.H.H.); [email protected] (P.C.T.) 2 Department of Biological Sciences, Bauru School of Dentistry, University of São Paulo, Bauru 17012-901, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-41-991-864-747 Abstract: Temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD) is a multifactorial condition that impairs human’s health and quality of life. Its etiology is still a challenge due to its complex development and the great number of different conditions it comprises. One of the most common forms of TMD is anterior disc displacement without reduction (DDWoR) and other TMDs with distinct origins are condylar hyperplasia (CH) and mandibular dislocation (MD). Thus, the aim of this study is to identify the protein expression profile of synovial fluid and the temporomandibular joint disc of patients diagnosed with DDWoR, CH and MD. Synovial fluid and a fraction of the temporomandibular joint disc were collected from nine patients diagnosed with DDWoR (n = 3), CH (n = 4) and MD (n = 2). Samples were subjected to label-free nLC-MS/MS for proteomic data extraction, and then bioinformatics analysis were conducted for protein identification and functional annotation. The three Citation: Doetzer, A.D.; Herai, R.H.; TMD conditions showed different protein expression profiles, and novel proteins were identified Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Trevilatto, P.C. -

(MCPH1) in Cetaceans Michael R

Wayne State University Wayne State University Associated BioMed Central Scholarship 2011 Phylogeny and adaptive evolution of the brain- development gene microcephalin (MCPH1) in cetaceans Michael R. McGowen University of California, [email protected] Stephen H. Montgomery University of Cambridge, [email protected] Clay Clark University of California, Riverside, [email protected] John Gatesy University of California, Riverside, [email protected] Recommended Citation McGowen et al.: Phylogeny and adaptive evolution of the brain-development gene microcephalin (MCPH1) in cetaceans. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2011 11:98. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/biomedcentral/72 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Associated BioMed Central Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. McGowen et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2011, 11:98 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/11/98 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Phylogeny and adaptive evolution of the brain-development gene microcephalin (MCPH1) in cetaceans Michael R McGowen1,2*, Stephen H Montgomery3, Clay Clark1 and John Gatesy1 Abstract Background: Representatives of Cetacea have the greatest absolute brain size among animals, and the largest relative brain size aside from humans. Despite this, genes implicated in the evolution of large brain size in primates have yet to be surveyed in cetaceans. Results: We sequenced ~1240 basepairs of the brain development gene microcephalin (MCPH1) in 38 cetacean species. Alignments of these data and a published complete sequence from Tursiops truncatus with primate MCPH1 were utilized in phylogenetic analyses and to estimate ω (rate of nonsynonymous substitution/rate of synonymous substitution) using site and branch models of molecular evolution. -

Building the Centriole: Plk4 Phosphorylates Stil To

BUILDING THE CENTRIOLE: PLK4 PHOSPHORYLATES STIL TO DIRECT PROCENTRIOLE ASSEMBLY by Tyler C. Moyer A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Baltimore, Maryland May, 2019 © Tyler C. Moyer 2019 All rights reserved Abstract Centrioles are small microtubule-based cellular structures that form the centrosome, the cell’s major microtubule-organizing center responsible for forming the bipolar spindle in mitosis. Each centriole duplicates exactly once per cell cycle at the onset of S phase by forming one new centriole on the wall of each of the two pre-existing parental centrioles. Polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4) has emerged as an upstream master regulator of centriole biogenesis, but how PLK4’s activity is regulated to control centriole duplication specifically at the G1/S phase transition remains unclear. Here, we used CRISPR genome engineering to create a chemical genetic system in which endogenous PLK4 can be specifically inhibited using a cell-permeable ATP analog. Using this system, we demonstrate that the centriolar localization of the core centriole component STIL requires continued PLK4 activity. Most importantly, we show that direct binding of STIL to PLK4 activates PLK4 by promoting self-phosphorylation of the kinase’s activation loop. PLK4 subsequently phosphorylates STIL at two distant sites to promote centriole assembly. One site allows STIL to bind to and recruit SAS6, the major component of the centriolar cartwheel, the inner framework of the centriole governing its architecture. The other site allows STIL to increase its binding to and promote the stable integration of CPAP, the centriole protein that links the cartwheel to the centriole’s outer microtubule walls. -

Pdf Breuss No 3

© 2016. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Development (2016) 143, 1126-1133 doi:10.1242/dev.131516 RESEARCH ARTICLE Mutations in the murine homologue of TUBB5 cause microcephaly by perturbing cell cycle progression and inducing p53-associated apoptosis Martin Breuss1, Tanja Fritz1, Thomas Gstrein1, Kelvin Chan1,2, Lyubov Ushakova1, Nuo Yu1, Frederick W. Vonberg1,3, Barbara Werner1, Ulrich Elling4 and David A. Keays1,* ABSTRACT abnormalities (Breuss et al., 2012; Ngo et al., 2014). Tubb5 is Microtubules play a crucial role in the generation, migration and widely expressed throughout embryonic development, and is differentiation of nascent neurons in the developing vertebrate brain. enriched in the developing cortex, where it is found in radial glial Mutations in the constituents of microtubules, the tubulins, are known to progenitors, intermediate progenitors and postmitotic neurons. As is cause an array of neurological disorders, including lissencephaly, true for the vast majority of tubulin mutations that cause human TUBB5 de novo polymicrogyria and microcephaly. In this study we explore the disease, those in are heterozygous and . The genetic and cellular mechanisms that cause TUBB5-associated preponderance of such mutations and absence of disease-causing microcephaly by exploiting two new mouse models: a conditional null alleles has led to the assertion that tubulin mutations act by a E401K knock-in, and a conditional knockout animal. These mice gain-of-function mechanism rather than haploinsufficiency (Hu present with profound microcephaly due to a loss of upper-layer et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2010). neurons that correlates with massive apoptosis and upregulation of Here, we investigate this contention by generating an E401K p53. -

STIL Balancing Primary Microcephaly and Cancer Dhruti Patwardhan1,2, Shyamala Mani1,3, Sandrine Passemard1,4, Pierre Gressens1,5 and Vincent El Ghouzzi1

Patwardhan et al. Cell Death and Disease (2018) 9:65 DOI 10.1038/s41419-017-0101-9 Cell Death & Disease REVIEW ARTICLE Open Access STIL balancing primary microcephaly and cancer Dhruti Patwardhan1,2, Shyamala Mani1,3, Sandrine Passemard1,4, Pierre Gressens1,5 and Vincent El Ghouzzi1 Abstract Cell division and differentiation are two fundamental physiological processes that need to be tightly balanced to achieve harmonious development of an organ or a tissue without jeopardizing its homeostasis. The role played by the centriolar protein STIL is highly illustrative of this balance at different stages of life as deregulation of the human STIL gene expression has been associated with either insufficient brain development (primary microcephaly) or cancer, two conditions resulting from perturbations in cell cycle and chromosomal segregation. This review describes the recent advances on STIL functions in the control of centriole duplication and mitotic spindle integrity, and discusses how pathological perturbations of its finely tuned expression result in chromosomal instability in both embryonic and postnatal situations, highlighting the concept that common key factors are involved in developmental steps and tissue homeostasis. Facts Open questions ● STIL is a cell cycle-regulated protein specifically ● Centrosome amplification is seen both in cancer and recruited at the mitotic centrosome to promote the in MCPH phenotype. How is the context important 1234567890 1234567890 duplication of centrioles in dividing cells. in determining the phenotype? ● Complete loss of STIL results in no centrosomes, no ● Is presence of STIL in the centrosome important in cilia, and is not compatible with life. determining cell fate? ● By contrast, residual or increased expression of STIL ● STIL has several binding partners. -

Homozygous STIL Mutation Causes Holoprosencephaly and Microcephaly in Two Siblings

RESEARCH ARTICLE Homozygous STIL Mutation Causes Holoprosencephaly and Microcephaly in Two Siblings Charlotte Mouden1, Marie de Tayrac1,7, Christèle Dubourg1,3, Sophie Rose1, Wilfrid Carré3, Houda Hamdi-Rozé1,3, Marie-Claude Babron4, Linda Akloul5, Bénédicte Héron-Longe6, Sylvie Odent1,5, Valérie Dupé1, Régis Giet2, Véronique David1,3* 1 Institut de Génétique et Développement de Rennes, Equipe Génétique des Pathologies Liées au Développement, Faculté de Médecine, Université de Rennes 1, 35043 Rennes, France, 2 Institut de Génétique et Développement de Rennes, Equipe Cytosquelette et Prolifération Cellulaire, Faculté de Médecine, Université de Rennes 1, 35043 Rennes, France, 3 Laboratoire de Génétique Moléculaire et Génomique, CHU Pontchaillou, 35033 Rennes, France, 4 Inserm U946, Variabilité Génétique et Maladies Humaines, Université Paris-Diderot, 75010 Paris, France, 5 Service de Génétique Clinique, Hôpital Sud, 35200 Rennes, France, 6 Service de Pédiatrie, Hôpital Jean Verdier, APHP, 93140 Bondy, France, 7 Plateforme Génomique Santé, Biosit, Université Rennes 1, 35033 Rennes, France * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Citation: Mouden C, de Tayrac M, Dubourg C, Rose Abstract S, Carré W, Hamdi-Rozé H, et al. (2015) Homozygous STIL Mutation Causes Holoprosencephaly (HPE) is a frequent congenital malformation of the brain characterized Holoprosencephaly and Microcephaly by impaired forebrain cleavage and midline facial anomalies. Heterozygous mutations in in Two Siblings. PLoS ONE 10(2): e0117418. 14 genes have been identified in HPE patients that account for only 30% of HPE cases, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0117418 suggesting the existence of other HPE genes. Data from homozygosity mapping and Academic Editor: Coro Paisan-Ruiz, Icahn School whole-exome sequencing in a consanguineous Turkish family were combined to identify a of Medicine at Mount Sinai, UNITED STATES homozygous missense mutation (c.2150G>A; p.Gly717Glu) in STIL, common to the two af- Received: September 8, 2014 fected children. -

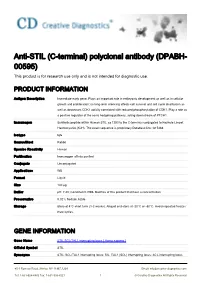

Anti-STIL (C-Terminal) Polyclonal Antibody (DPABH- 00595) This Product Is for Research Use Only and Is Not Intended for Diagnostic Use

Anti-STIL (C-terminal) polyclonal antibody (DPABH- 00595) This product is for research use only and is not intended for diagnostic use. PRODUCT INFORMATION Antigen Description Immediate-early gene. Plays an important role in embryonic development as well as in cellular growth and proliferation; its long-term silencing affects cell survival and cell cycle distribution as well as decreases CDK1 activity correlated with reduced phosphorylation of CDK1. Play a role as a positive regulator of the sonic hedgehog pathway, acting downstream of PTCH1. Immunogen Synthetic peptide within Human STIL aa 1250 to the C-terminus conjugated to Keyhole Limpet Haemocyanin (KLH). The exact sequence is proprietary.Database link: Q15468 Isotype IgG Source/Host Rabbit Species Reactivity Human Purification Immunogen affinity purified Conjugate Unconjugated Applications WB Format Liquid Size 100 μg Buffer pH: 7.40; Constituent: PBS. Batches of this product that have a concentration Preservative 0.02% Sodium Azide Storage Store at 4°C short term (1-2 weeks). Aliquot and store at -20°C or -80°C. Avoid repeated freeze / thaw cycles. GENE INFORMATION Gene Name STIL SCL/TAL1 interrupting locus [ Homo sapiens ] Official Symbol STIL Synonyms STIL; SCL/TAL1 interrupting locus; SIL, TAL1 (SCL) interrupting locus; SCL-interrupting locus 45-1 Ramsey Road, Shirley, NY 11967, USA Email: [email protected] Tel: 1-631-624-4882 Fax: 1-631-938-8221 1 © Creative Diagnostics All Rights Reserved protein; MCPH7; TAL-1-interrupting locus protein; SIL; DKFZp686O09161; Entrez Gene ID 6491 Protein Refseq NP_001041631 UniProt ID Q15468 Chromosome Location 1p32 Pathway Signaling events mediated by the Hedgehog family. -

Cell Cycle Arrest Through Indirect Transcriptional Repression by P53: I Have a DREAM

Cell Death and Differentiation (2018) 25, 114–132 Official journal of the Cell Death Differentiation Association OPEN www.nature.com/cdd Review Cell cycle arrest through indirect transcriptional repression by p53: I have a DREAM Kurt Engeland1 Activation of the p53 tumor suppressor can lead to cell cycle arrest. The key mechanism of p53-mediated arrest is transcriptional downregulation of many cell cycle genes. In recent years it has become evident that p53-dependent repression is controlled by the p53–p21–DREAM–E2F/CHR pathway (p53–DREAM pathway). DREAM is a transcriptional repressor that binds to E2F or CHR promoter sites. Gene regulation and deregulation by DREAM shares many mechanistic characteristics with the retinoblastoma pRB tumor suppressor that acts through E2F elements. However, because of its binding to E2F and CHR elements, DREAM regulates a larger set of target genes leading to regulatory functions distinct from pRB/E2F. The p53–DREAM pathway controls more than 250 mostly cell cycle-associated genes. The functional spectrum of these pathway targets spans from the G1 phase to the end of mitosis. Consequently, through downregulating the expression of gene products which are essential for progression through the cell cycle, the p53–DREAM pathway participates in the control of all checkpoints from DNA synthesis to cytokinesis including G1/S, G2/M and spindle assembly checkpoints. Therefore, defects in the p53–DREAM pathway contribute to a general loss of checkpoint control. Furthermore, deregulation of DREAM target genes promotes chromosomal instability and aneuploidy of cancer cells. Also, DREAM regulation is abrogated by the human papilloma virus HPV E7 protein linking the p53–DREAM pathway to carcinogenesis by HPV.Another feature of the pathway is that it downregulates many genes involved in DNA repair and telomere maintenance as well as Fanconi anemia.