The Vatard Sisters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Death of the City and the Survival of Urban Life Center of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona 2004 Conference Lectured at the Symposium “Urban Traumas

www.urban.cccb.org Richard Ingersoll The Death of the City and the Survival of Urban Life Center of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona 2004 Conference lectured at the symposium “Urban Traumas. The City and Disasters”. CCCB, 7-11 July 2004 Strolling through the cemetery of Montparnasse in Paris, I fantasize a poker game with an ideal community of the defunct that includes Marguerite Duras, Charles Baudelaire, Delphine Seyrig, and Samuel Beckett. Their modest burial markers rest alongside the ornate aedicules of the proud and powerful, belle époque generals and financiers. Looking around at the densely packed lanes lined with tombs, there seems to be no room left. The necropolis is so crowded that for a moment I have the infantile notion that no one else will be allowed to die. The Montparnasse cemetery is right in the midst of one of the busiest parts of the Left Bank, and to enter is to escape from the tedium of daily life, a place to contemplate the life of the past. In the background rises the immense black, glass-clad tower of Montparnasse, a soaring catacomb for modern offices. Life goes on in the city, overlooking the cemetery, but, as I will try to show, it was never the city itself that was alive. In fact I am often convinced while visiting cemeteries that the only reason the city became a place is because someone died there. René Girard in his theory of the scapegoat suggests that architecture began with stones used to lapidate a victim. «In the end», says Girard, «the tomb is the first and only cultural symbol». -

Limonaire Frères Paris, 1839 — 1936*

Carousel Organ , Issue No. 26 — January, 2006 Limonaire Frères Paris, 1839 — 1936* Andrea Stadler “Limonaire” is without any doubt the most famous name in the field of mechanical music. In 1906 it became (accord- ing to “le petit Robert de la langue française,” ed. 1986) a standardized name to be found in French dictionaries, gen- erally as a synonym for a carousel organ. There are several instruments bearing the name Limonaire found in muse- ums or in public or private collections, about which there is technical documentation. On the other hand, we knew almost nothing about “les Frères Limonaire” and the history of the firm, until a German university student, Andrea Stadler, took the time during the preparation of her doctorate, to do extensive research in the archives of the Records Office, commercial and notarial records, and elsewhere. Most of the private documents of the Limonaire family have disappeared. She also had the chance to interview some rare descendants of the family. She has given us the honour to publish in the Carousel Organ , for the first time in English, some parts of the results of her investigation. Philippe Rouillé First part: 1839-1886 The different establishments “Limonaire Frères” When examining the history of the “Limonaire Frères,” one finds that this firm has existed twice under this name in the history of musical instruments. The Bottin , a French commer- cial directory, mentions them from 1839 to 1841 and again from 1887 till 1920. After 1920, the Sociétés succeeding the Limonaire brothers took over a major part of the famous organ builders. -

Syllabus Paris

Institut de Langue et de Culture Française Spring Semester 2017 Paris, World Arts Capital PE Perrier de La Bâthie / [email protected] Paris, World Capital of Arts and Architecture From the 17th through the 20th centuries Since the reign of Louis XIV until the mid-20th century, Paris had held the role of World Capital of Arts. For three centuries, the City of Light was the place of the most audacious and innovative artistic advances, focusing on itself the attention of the whole world. This survey course offers students a wide panorama on the evolution of arts and architecture in France and more particularly in Paris, from the beginning of the 17th century to nowadays. The streets of the French capital still preserve the tracks of its glorious history through its buildings, its town planning and its great collections of painting, sculpture and decorative arts. As an incubator of modernity, Paris saw the rising of a new epoch governed – for better or worse – by faith in progress and reason. As literature and science, art participated in the transformations of society, being surely its more accurate reflection. Since the French Revolution, art have accompanied political and social changes, opened to the contestation of academic practice, and led to an artistic and architectural avant-garde driven to depict contemporary experience and to develop new representational means. Creators, by their plastic experiments and their creativity, give the definitive boost to a modern aesthetics and new references. After the trauma of both World War and the American economic and cultural new hegemony, appeared a new artistic order, where artists confronted with mass-consumer society, challenging an insane post-war modernity. -

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Arrondissement 1: Louvre Built in 1632 As a Masterpiece of Late Gothic Architecture

WHAT Architect WHERE Notes Arrondissement 1: Louvre Built in 1632 as a masterpiece of late Gothic architecture. The church’s reputation was strong enough of the time for it to be chosen as the location for a young Louis XIV to receive communion. Mozart also Church of Saint 2 Impasse Saint- chose the sanctuary as the location for his mother’s funeral. Among ** Unknown Eustace Eustache those baptised here as children were Richelieu, Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, future Madame de Pompadour and Molière, who was also married here in the 17th century. Amazing façade. Mon-Fri (9.30am-7pm), Sat-Sun (9am-7pm) Japanese architect Tadao Ando has revealed his plans to convert Paris' Bourse de Commerce building into a museum that will host one of the world's largest contemporary art collections. Ando was commissioned to create the gallery within the heritage-listed building by French Bourse de Commerce ***** Tadao Ando businessman François Pinault, who will use the space to host his / Collection Pinault collection of contemporary artworks known as the Pinault Collection. A new 300-seat auditorium and foyer will be set beneath the main gallery. The entire cylinder will be encased by nine-metre-tall concrete walls and will span 30 metres in diameter. Opening soon The Jardin du Palais Royal is a perfect spot to sit, contemplate and picnic between boxed hedges, or shop in the trio of beautiful arcades that frame the garden: the Galerie de Valois (east), Galerie de Montpensier (west) and Galerie Beaujolais (north). However, it's the southern end of the complex, polka-dotted with sculptor Daniel Buren's Domaine National du ***** 8 Rue de Montpensier 260 black-and-white striped columns, that has become the garden's Palais-Royal signature feature. -

Brancusi Journey – a Revival of a Paradoxical Modern European Tradition

Horizons for sustainability „Constantin Brâncuşi” University of Târgu-Jiu, Issue /2020 BRANCUSI JOURNEY – A REVIVAL OF A PARADOXICAL MODERN EUROPEAN TRADITION Lavinia TOMESCU1 ABSTRACT. THIS ARTICLE PRESENTS A POSSIBLE EUROPEAN CULTURAL ROUTE AND THE TOURIST CIRCUIT ON BRÂNCUȘI'S TRACKS IN PARIS. CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI REPRESENTS THE COMMON CATALYST, THE FORCE VECTOR FOR THE ENTIRE ROMANIAN SPIRITUALITY, THE EXPONENT OF THE ROMANIAN CULTURE BASED ON THE TRADITIONAL AUTHENTIC. ROMANIANS EVERYWHERE FIND THEIR IDENTITY IN THE WORK OF THE SYMBOL OF THE TRADITIONAL ROMANIAN SPIRITUALITY, CONSTANTIN BRANCUSI, AS A BINDER OF THE RECONNECTION TO THE ORIGINS OF THE TRADITIONAL ROMANIAN CULTURE. CULTURAL ITINERARIES ARE CONSIDERED AN ELEMENT OF INNOVATION IN WHICH THEY SHOULD SUPPORT THE PROMOTION OF THE EUROPEAN IDENTITY AND THE COMMON HERITAGE. CULTURAL ROUTES ARE ITINERARIES THAT GATHER TOGETHER IMPORTANT ELEMENTS OF HERITAGE, WHICH STAND AS TESTIMONY AND ILLUSTRATE SPECIFIC PERIODS AND EVENTS OF EUROPEAN HISTORY. THEY ARE CHARACTERIZED BY MOBILITY AND ALSO IMPLY AN INTANGIBLE AND SPATIAL DYNAMIC THAT THE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE DOES NOT POSSESS, WHICH IS MORE STATIC AND LIMITED IN NATURE. BRÂNCUȘI ROUTE IS THE ITINERARY THAT HE TRAVELED ON FOOT FROM HOBIȚA FROM GORJ TO PARIS. KEYWORDS: ITINERARY, SCULPTOR, BRÂNCUȘI, TOURIST CIRCUIT, CULTURAL ROUTE. INTRODUCTION The European Cultural Route Constantin Brâncuşi - The road to artistic metamorphosis can be a true bridge between Eastern Europe and Western Europe. This route is deeply rooted in the traditions and common European cultural heritage, uniting places with a deep spiritual significance. The greatest sculptor of the 20th century, Constantin Brâncuşi, a central figure in the modern artistic movement is considered the parent of modern sculpture. -

The Invisible “Sculpteuse”: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-Century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels

Marjan Sterckx The Invisible “Sculpteuse”: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 7, no. 2 (Autumn 2008) Citation: Marjan Sterckx, “The Invisible ‘Sculpteuse’: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth- century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 7, no. 2 (Autumn 2008), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/autumn08/90-the-invisible- sculpteuse-sculptures-by-women-in-the-nineteenth-century-urban-public-spacelondon-paris- brussels. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2008 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Sterckx: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-Century Urban Public Space–London, Paris, Brussels Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 7, no. 2 (Autumn 2008) The Invisible “Sculpteuse”: Sculptures by Women in the Nineteenth-century Urban Public Space—London, Paris, Brussels[1] by Marjan Sterckx Introduction The Dictionary of Employment Open to Women, published by the London Women’s Institute in 1898, identified the kinds of commissions that women artists opting for a career as sculptor might expect. They included light fittings, forks and spoons, racing cups, presentation plates, medals and jewelry, as well as “monumental work” and the stone decoration of domestic facades, which was said to be “nice work, but poorly paid,” and “difficult to obtain without -

WALK 3 | Montparnasse

WALK 3 | Montparnasse Start – Metro Station, Sèvres Lecourbe, Line 6 Approximate Length: 4.3 km 11 16 15 12 14 13 N U = Underground Metro Station = Optional Route After exiting the Metro station, walk toward Place Henri Queuille. Cross Rue Lecourbe onto Boulevard Pasteur. At the beginning of the boulevard is a Wallace Fountain. Fountain 11 2 Boulevard Pasteur, 15th Arr. You will find this fountain at the beginning of the grand Boulevard Pasteur under the elevated tracks of a Metro line. Like most Wallace Fountains, very small placards attached to 11 the pedestal base give information about the mineral content and the source of the free water it dispenses. Continue along Boulevard Pasteur. On your right you will pass the Lycée Buffon, a stately academic building used as a secondary school. Walk on this boulevard until it ends. Pass through Place des Martyrs du Lycée Buffon, a square dedicated to five students killed for participating in the Resistance during Nazi occupation. Soon you will reach Place de Catalogne, a large traffic circle. Proceed around the traffic circle and take Rue du Château a short distance until you come to Place de l’Abbé J. Lebeuf. There you will find a Wallace Fountain. Fountain 12 Place de l’Abbé Jean Lebeuf, 14th Arr. This fountain’s location is interesting because, from one angle, the fountain is framed by the large archway of the building behind it. The 12 fountain is very visible in the open area and is surrounded by benches. Unlike ©Barbara Lambesis ©Barbara Lambesis many other locations where the fountains blend into the streetscape, this fountain is a center piece, the main element of the square. -

Peter's Paris: Les Halles 16/05/09 11:12

Peter's Paris: Les Halles 16/05/09 11:12 RECHERCHER LE BLOG SIGNALER LE BLOG Blog suivant» PETER'S PARIS PARIS AS SEEN BY A RETIRED SWEDE. 17.4.09 LINK TO MY PREVIOUS BLOG Les Halles My previous blog, PHO, was in operation for a year as from March 2007. It contains similar posts as this one, basically talking about different well known or more secrete sites in Paris. You can reach it by clicking HERE. You can also see photos - only - on my photo-blogs (previous one, present one). You can also find some of my photos on IPERNITY. ABOUT ME PETER A retired Swede, living in Paris. This is a new blog, started in March 2008. My previous ones This is what until the 70's used to be can be reached on the following called the "belly of Paris", when for addresses: http://peter- hygienic and congestion reasons the olson.blogspot.com/ and http://peter- activities which used to take place here were transferred to new premises in the olson-photos.blogspot.com/ suburbs (Rungis). What usually goes under the name "Les Halles" was from VIEW MY COMPLETE PROFILE the 12th century until around 1970 Paris' central market (including wholesales) for fresh products. During the second half of OTHER BLOGS ABOUT PARIS the 19th century the so famous "Baltard pavilions" were constructed, thus D'HIER A AUJOURD'HUI demolished during the 70's. Several projects were planned and even launched Every Moment and abandoned for new activities on this large area. In the meantime, and for I Prefer Paris years, this was known as "le trou (the hole) des Halles". -

Jewish Cemeteries in France

77 Jewish Cemeteries in France Gérard Nahon The medieval cemeteries of the Jewish communities disap- peared after the expulsions of 1306, 1394 and 1502. Eight- een museums keep steles, slabs, and fragments from these cemeteries: Aix-en-Provence, Antibes, Bourges, Carpentras, Clermont-Ferrand, Dijon, Lyon, Mâcon, Mantes-la-Jolie, Nancy, Narbonne, Nîmes, Orléans, Paris, Saint-Germain-en- Laye, Strasbourg, Toulouse, and Vienne.1 Theses remains, coupled with archival data, may give an idea of the funeral landscape of French medieval Jewry. There is a permanent exhibition of medieval Jewish tombstones at the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme in Paris. On the eve of the French Revolution, 80 Jewish cemeteries existed in the outlying areas of the kingdom: 2 in the French States of the Holy See, i. e. Avignon and Comtat Venaissin (Avignon, Carpentras, Cavaillon, Lisle-sur-la Sorgue); in Alsace and Lorraine which were annexed to the kingdom in 1648; in the south-west of Aquitaine (Bayonne, Bidache, Bordeaux, Labastide-Clairence, Peyrehorade), where since the 16th century Portuguese and Spanish New Christians gradually returned to Judaism. Most of today’s Jewish cemeteries – about 298 – were opened following the decrees or laws of 6 and 15 May 1791, 23 prairial year XII (= 12 June 1804), and 14 November 1881. Today, four historic and legal categories of cemeteries are in existence: 1. old community cemetery, 2. independent cemetery belonging to the municipality, Fig. 1 Cemetery of the Portuguese Jews (1780 –1810), 3. l’enclos israélite in the communal cemetery opened in 46 avenue de Flandre, Paris (Photo: Gérard Nahon) the 19th century, 4. -

Six Feet in All Fairness, in Search of Lost Time Isn’T Easy to Finish, Neither Is His Crypt Easy to Find

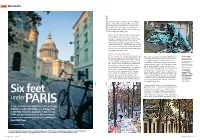

NOSTALGIA t was a good day to go see my heroes. Splinters of the sun were lighting my path, Frenchmen were throwing away come-hither looks, my feet were tapping to an invisible harp. Paris was coming together like a well-directed scene. too bad all my heroes had gone underground. IWriters over the last two centuries have hungered for Paris like loners hunger for love. they came looking for inspiration and freedom; they left with Ulysses and A Moveable Feast. this is the city where they failed and succeeded, lost their hearts and found a few words. And though there’s nothing more I’d like than to bump into them, à la Midnight in Paris, I have to contend myself with walking past their graves, head bent in awe. GHOSTS OF WRITERS PAST My first stop was Père-Lachaise Cemetery, the most Most come here to visit rock god Jim Morrison, but Above: A statue famous resting place in the world with the likes of I was interested in the man who was the life and of a woman with a headscarf placing a Chopin, Modigliani and Édith Piaf within. the site soul of literary parties in the late 19th century— was so sprawling, it could easily be mistaken for a laurel wreath around Oscar Wilde. Hounded by a Victorian government the head of the park. Ivory-coloured headstones were shaded with over his choices in love, Oscar Wilde died poor and deceased inside Père chestnut trees, creating a gorgeous foil of silver bereft. History, though, has been kinder to him. -

Copyrighted Material

19_007478 bindex.qxp 7/27/06 11:08 PM Page 333 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Arrondissements 8th (Champs-Elysées/ 1st (Musée du Louvre/Les Madeleine), 68 Halles), 14, 66, 231–232 accommodations, 98–103 Académie de la Bière, 288 accommodations, 84–89 attractions index, 183 Accommodations, 81–123. See attractions, 183, 229–231 restaurants, 149–157 also Accommodations Index restaurants, 131–139 shopping, 253 bathrooms, 89 shopping, 253 9th (Opéra Garnier/Pigalle), 68 best, 5–7, 82–83 2nd (La Bourse), 66 accommodations, 95–96 Chartres, 304 accommodations, 90 attractions index, 184 Disneyland Paris, 309–311 restaurants, 139 restaurants, 143–145 family-friendly, 82, 93 shopping, 253 shopping, 254 Fontainebleau, 314–315 3rd (Le Marais), 13, 66 10th (Gare du Nord/Gare Giverny, 306 accommodations, 90–92 de l’Est), 68 government ratings, 81 attractions index, 183 restaurants, 145–146 Left Bank, 81–82, 106–123 restaurants, 139–141 11th (Opéra Bastille), 68–69 Right Bank, 81–82, 84–105 shopping, 253 accommodations, 96–97 websites, 44 walking tour, 245–250 attractions index, 184 what’s new in, 1 4th (Ile de la Cité/ cafés, 181 Address, finding an, 65 Ile St-Louis & Beaubourg), restaurants, 146–148 African items, shopping for, 13, 66–67 shopping, 263 260 accommodations, 92–95 12th (Bois de Vincennes/ Afternoon tea, 3, 138, 142 attractions index, 183 Gare de Lyon), 69 Airfares, 44, 52 cafés, 179–180 accommodations, 97–98 Airlines , 47–48 restaurants, 141–143 attractions index, 184 long-haul flights, 38, 49–50 -

Connecting Existing Cemeteries Saving Good Soils (For Livings)

sustainability Concept Paper Connecting Existing Cemeteries Saving Good Soils (for Livings) Riccardo Scalenghe 1 and Ottorino-Luca Pantani 2,* 1 Dipartimento di Scienze Agrarie, Alimentari e Forestali (SAAF), Università degli Studi di Palermo Viale delle Scienze 13, 90128 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 2 Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie Agrarie, Alimentari Ambientali e Forestali (DAGRI), Università degli Studi di Firenze, Piazzale Cascine 28, 50144 Firenze, Italy * Correspondence: olpantani@unifi.it Received: 13 November 2019; Accepted: 19 December 2019; Published: 21 December 2019 Abstract: Background: Urban sprawl consumes and degrades productive soils worldwide. Fast and safe decomposition of corpses requires high-quality functional soils, and land use which competes with both agriculture and buildings. On one hand, cremation does not require much land, but it has a high energy footprint, produces atmospheric pollution, and is unacceptable to some religious communities. On the other hand, as exhumations are not practiced, “green burials” require more surface area than current burial practices, so a new paradigm for managing land use is required. Conclusions: In this paper, we propose a concept for ‘green belt communalities’ (i.e., ecological corridors with multiple, yet flexible, uses and services for future generations). With the expansion of urban centers, ecological corridors gradually disappear. Cemeteries for burial plots preclude alternative uses of the land for a long time. By combining these two aspects (need for connectivity and land take imposed by cemeteries), two positive results can be achieved: protecting memories of the past and connecting ecosystems with multiple-use corridors. This new paradigm works best in flat or hilly terrain where there are already several urban agglomerations that contain traditional cemeteries.