Carrot & Parsnip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carrot Butter–Poached Halibut, Anchovy-Roasted Carrots, Fennel

Carrot Butter–Poached Halibut, Anchovy-Roasted Carrots, Fennel 2 pounds (900 g) small carrots, with tops 31⁄2 cups (875 g) unsalted butter 3 anchovy fillets, minced 3 lemons Kosher salt 2 cups (500 ml) fresh carrot juice 3 cloves garlic, crushed, plus 1 whole clove garlic 1 bay leaf Zest of 1 orange 1⁄4 cup (60 ml) extra-virgin olive oil 4 halibut fillets, each about 6 ounces (185 g) Maldon flake salt Fennel Salad 1 fennel bulb, sliced 1⁄8 inch (3 mm) thick using a mandoline 2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil 2 tablespoons chopped chives 1 tablespoon chopped white anchovies (boquerones) Kosher salt and freshly ground black Pepper 1. Preheat the oven to 350°F (180°C). 2. Remove the carrot tops, wash, and set aside. Peel the carrots and halve them lengthwise. In a saute pan over medium heat, melt . cup (125 g) of the butter with the anchovies and the grated zest from two of the lemons. Add the carrots and season with kosher salt. Transfer to a baking sheet, spread in a single layer, and roast in the oven until slightly softened but still a little crunchy, about 12 minutes. Remove from oven and toss with the juice of one lemon. 3. In a shallow saute pan over medium heat, combine the carrot juice, the crushed garlic, bay leaf, and orange zest. Cook until reduced by threequarters, about 10 minutes. Add the remaining 3 cups (750 g) butter and stir until melted, then reduce the heat to very low and keep warm. -

Carrots, Celery, Dehydration & Osmosis

CARROTS, CELERY, DEHYDRATION & OSMOSIS OVERVIEW Students will investigate dehydration by soaking carrots and celery in salt and fresh water and observing the effects of osmosis on living organisms. Animals and plants that live in the ocean usually have a high salt level within them in order to avoid dehydration. CONCEPTS • Water molecules move across a membrane to higher levels of salt concentration through a pro- cess called osmosis. • Animals and plants that live in the ocean usually have a high salt content. On the other hand, animals and plants that are not adapted to salt water may have a low salt content, and thus become dehydrated when placed in salt water. MATERIALS For each group: • Salt water • Fresh water • Carrots • Celery • Containers (bowls, glasses, cups) PREPARATION Salt water can be created by simply putting a large quantity of salt into some water and stirring. Warm water will cause the salt to dissolve easier. If you wish to simulate the salt content of the ocean (optional), put 35 milligrams of salt into 965 milliliters of water. This exercise can be done as a class activity/demonstration, or students can be split into small groups. Each group will need a full set of materials. There should be at least one period where the vegetables are left in water for an extended period to get the desired effect. You may therefore wish to extend this activity throughout the day, or for more dramatic and distinctive results, conduct it over two to three days. Alternatively, you can reduce the time needed for this activity if you begin with both crisp and limp vegetables. -

Integrated Carrots

Integrated management of Pythium diseases of carrots E Davison and A McKay Department of Agriculture, Western Australia Project Number: VG98011 VG98011 This report is published by Horticulture Australia Ltd to pass on information concerning horticultural research and development undertaken for the vegetable industry. The research contained in this report was funded by Horticulture Australia Ltd with the financial support of the vegetable industry. All expressions of opinion are not to be regarded as expressing the opinion of Horticulture Australia Ltd or any authority of the Australian Government. The Company and the Australian Government accept no responsibility for any of the opinions or the accuracy of the information contained in this report and readers should rely upon their own enquiries in making decisions concerning their own interests. ISBN 0 7341 0333 6 Published and distributed by: Horticultural Australia Ltd Level 1 50 Carrington Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone: (02) 8295 2300 Fax: (02) 8295 2399 E-Mail: [email protected] © Copyright 2001 Horticulture Australia FINAL REPORT HORTICULTURE AUSTRALIA PROJECT VG98011 INTEGRATED MANAGEMENT OF PYTHIUM DISEASES OF CARROTS E. M. Davison and A. G. McKay Department of Agriculture, Western Australia DEPARTMENT OF Agriculture Horticulture Australia September 2001 HORTICULTURE AUSTRALIA PROJECT VG 98011 Principal Investigator Elaine Davison Research Officer, Crop Improvement Institute, Department of Agriculture, Locked Bag 4, Bentley Deliver Centre, Western Australia 6983 Australia Email: edavisonfSjagric.wa.gov.au This is the final report of project VG 98011 Integrated management of Pythium diseases of carrots. It covers research into the cause(s) of cavity spot and related diseases in carrot production areas in Australia, together with information on integrated disease control. -

Proposal for Plot Based Plant Phenology Sampling in Puale Bay, Alaska (Adapted from Long Term Ecological Monitoring Program, Vegetation Sampling Protocols 2006)

Plant Phenology Puale Bay 2010 Proposal for Plot Based Plant Phenology Sampling in Puale Bay, Alaska (Adapted from Long Term Ecological Monitoring Program, Vegetation Sampling Protocols 2006) Stacey E. Pecen U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alaska Peninsula/Becharof NWR, P.O. Box 277, King Salmon, AK 99613 BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES Phenology, the timing of major biological events during a plant or animal’s life, can be monitored to detect changes in climate. Major events are called phenophases: leaf emergence, flowering, fruit ripening, and senescing. According to Menzel and Estrella (2001), plant phenology studies have shown that the average growing season is increasing by 0.2 days/year. It is especially important to monitor changes in higher latitudes, such as Alaska, where global warming is expected to occur earlier and at a greater magnitude (Henry and Molau 1997). The Northern Hemisphere (above 40o N) has experienced an increase in temperature of at least 0.5oC/decade from 1966-1995 (Serreze et al. 2000, Euskirchen et al. 2009). Monitoring species abundance and diversity is also vital. Environmental conditions dictate the composition of plant communities. Changes can occur over time, disrupting the balance of these interactions. In a nine year study at Toolik Lake, AK, Chapin et al. (1995) found that species richness declined 30-50% when the mean temperature was increased by 3.5˚C. Forbs and grasses decreased in abundance while woody species, such as Betula spp., increased. Changes in species abundance in regions of the arctic, as a result of warming, were also noted by Euskirchen et al. (2009). -

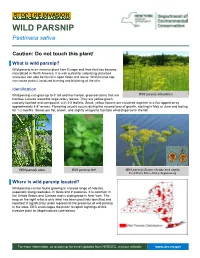

Wild Parsnip Fact Sheet

WILD PARSNIP Pastinaca sativa Caution: Do not touch this plant! ▐ What is wild parsnip? Wild parsnip is an invasive plant from Europe and Asia that has become naturalized in North America. It is well suited for colonizing disturbed areas but can also be found in open fields and lawns. Wild parsnip sap can cause painful, localized burning and blistering of the skin. Identification Wild parsnip can grow up to 5' tall and has hollow, grooved stems that are Wild parsnip infestation hairless. Leaves resemble large celery leaves. They are yellow-green, coarsely toothed and compound, with 3-5 leaflets. Small, yellow flowers are clustered together in a flat-topped array approximately 3-8″ across. Flowering usually occurs during the second year of growth, starting in May or June and lasting for 1-2 months. Seeds are flat, brown, and slightly winged to facilitate wind dispersal in the fall. Wild parsnip stem Wild parsnip leaf Wild parsnip flower cluster and seeds Seed Photo: Bruce Ackley, Bugwood.org ▐ Where is wild parsnip located? Wild parsnip can be found growing in a broad range of habitats, especially along roadsides, in fields and in pastures. It is common in the United States and Canada and is widespread in New York. The map on the right reflects only what has been positively identified and reported; it significantly under represents the presence of wild parsnip in the state. DEC encourages the public to report sightings of this invasive plant to iMapInvasives (see below). For more information, or to sign-up for email updates from NYSDEC, visit our website: www.dec.ny.gov ▐ Why is wild parsnip dangerous? Wild parsnip sap contains chemicals called furanocoumarins which can make skin more vulnerable to ultraviolet radiation. -

Companion Plants for Better Yields

Companion Plants for Better Yields PLANT COMPATIBLE INCOMPATIBLE Angelica Dill Anise Coriander Carrot Black Walnut Tree, Apple Hawthorn Basil, Carrot, Parsley, Asparagus Tomato Azalea Black Walnut Tree Barberry Rye Barley Lettuce Beans, Broccoli, Brussels Sprouts, Cabbage, Basil Cauliflower, Collard, Kale, Rue Marigold, Pepper, Tomato Borage, Broccoli, Cabbage, Carrot, Celery, Chinese Cabbage, Corn, Collard, Cucumber, Eggplant, Irish Potato, Beet, Chive, Garlic, Onion, Beans, Bush Larkspur, Lettuce, Pepper Marigold, Mint, Pea, Radish, Rosemary, Savory, Strawberry, Sunflower, Tansy Basil, Borage, Broccoli, Carrot, Chinese Cabbage, Corn, Collard, Cucumber, Eggplant, Beet, Garlic, Onion, Beans, Pole Lettuce, Marigold, Mint, Kohlrabi Pea, Radish, Rosemary, Savory, Strawberry, Sunflower, Tansy Bush Beans, Cabbage, Beets Delphinium, Onion, Pole Beans Larkspur, Lettuce, Sage PLANT COMPATIBLE INCOMPATIBLE Beans, Squash, Borage Strawberry, Tomato Blackberry Tansy Basil, Beans, Cucumber, Dill, Garlic, Hyssop, Lettuce, Marigold, Mint, Broccoli Nasturtium, Onion, Grapes, Lettuce, Rue Potato, Radish, Rosemary, Sage, Thyme, Tomato Basil, Beans, Dill, Garlic, Hyssop, Lettuce, Mint, Brussels Sprouts Grapes, Rue Onion, Rosemary, Sage, Thyme Basil, Beets, Bush Beans, Chamomile, Celery, Chard, Dill, Garlic, Grapes, Hyssop, Larkspur, Lettuce, Cabbage Grapes, Rue Marigold, Mint, Nasturtium, Onion, Rosemary, Rue, Sage, Southernwood, Spinach, Thyme, Tomato Plant throughout garden Caraway Carrot, Dill to loosen soil Beans, Chive, Delphinium, Pea, Larkspur, Lettuce, -

Powdery Mildew – a New Disease of Carrots

SEPTEMBER 2009 PRIMEFACT 616 SECOND EDITION Powdery mildew – a new disease of carrots Andrew Watson management strategies for carrot powdery mildew”. The project is due to finish in 2011. Plant Pathologist, Plant Health Sciences, Yanco Agricultural Institute The project is based in the three states that have recorded the disease i.e.. New South Wales, Powdery mildew has been found on a carrot crops Tasmania and South Australia. The collaborators in in three states of Australia. The first finding of the Tasmania include Hoong Pung (Peracto Pty Ltd.) disease was in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area and in South Australia , Barbara Hall (Sardi). (MIA) of New South Wales in 2007. It has This project is looking at the spread of powdery subsequently been found in Tasmania and South mildew on carrots and best methods of managing Australia in 2008. While the organism causing the the disease using fungicides, varietal resistance disease is commonly found in parsnip crops, (where available) and softer alternatives. powdery mildew has not previously been recorded on carrots in Australia. Fungicide options. Cause Fungicide trials in New South Wales and Tasmania have shown that applications of sulphur The causal agent is Erysiphe heraclei, the same successfully controls the disease as do Amistar and fungus that affects parsnips and other members of Folicur. The latter products have a permit for the Apiaceae family. Preliminary information has powdery mildew control. Sulphur has a general indicated that this form of E. heraclei does not infect vegetable registration. However alternative products parsnip or parsley, indicating that it may be specific need to be investigated as resistance to fungicides to carrots. -

Elicitation of Grapevine Defense Responses Against Plasmopara Viticola , the Causal Agent of Downy Mildew

Elicitation of grapevine defense responses against Plasmopara viticola , the causal agent of downy mildew Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Naturwissenschaftlichen Fachbereiche der Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen Durchgeführt am Institut für Phytopathologie und Angewandte Zoologie Vorgelegt von M.Sc. Moustafa Selim aus Kairo, Ägypten Dekan: Prof. Dr. Peter Kämpfer 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Karl-Heinz Kogel 2. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Tina Trenczek Dedication / Widmung I. DEDICATION / WIDMUNG: Für alle, die nach Wissen streben Und ihren Horizont erweitern möchten bereit sind, alles zu geben Und das Unbekannte nicht fürchten Für alle, die bereit sind, sich zu schlagen In der Wissenschaftsschlacht keine Angst haben Wissen ist Macht **************** For all who seek knowledge And want to expand their horizon Who are ready to give everything And do not fear the unknown For all who are willing to fight In the science battle Who have no fear Because Knowledge is power I Declaration / Erklärung II. DECLARATION I hereby declare that the submitted work was made by myself. I also declare that I did not use any other auxiliary material than that indicated in this work and that work of others has been always cited. This work was not either as such or similarly submitted to any other academic authority. ERKLÄRUNG Hiermit erklare ich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbststandig angefertigt und nur die angegebenen Quellen and Hilfsmittel verwendet habe und die Arbeit der anderen wurde immer zitiert. Die Arbeit lag in gleicher oder ahnlicher Form noch keiner anderen Prufungsbehorde vor. II Contents III. CONTENTS I. DEDICATION / WIDMUNG……………...............................................................I II. ERKLÄRUNG / DECLARATION .…………………….........................................II III. -

Culturing and Direct DNA Extraction Find Different Fungi From

Research CulturingBlackwell Publishing Ltd. and direct DNA extraction find different fungi from the same ericoid mycorrhizal roots Tamara R. Allen1, Tony Millar1, Shannon M. Berch2 and Mary L. Berbee1 1Department of Botany, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver BC, V6T 1Z4, Canada; 2Ministry of Forestry, Research Branch Laboratory, 4300 North Road, Victoria, BC V8Z 5J3, Canada Summary Author for correspondence: • This study compares DNA and culture-based detection of fungi from 15 ericoid Mary L. Berbee mycorrhizal roots of salal (Gaultheria shallon), from Vancouver Island, BC Canada. Tel: (604) 822 2019 •From the 15 roots, we PCR amplified fungal DNAs and analyzed 156 clones that Fax: (604) 822 6809 Email: [email protected] included the internal transcribed spacer two (ITS2). From 150 different subsections of the same roots, we cultured fungi and analyzed their ITS2 DNAs by RFLP patterns Received: 28 March 2003 or sequencing. We mapped the original position of each root section and recorded Accepted: 3 June 2003 fungi detected in each. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00885.x • Phylogenetically, most cloned DNAs clustered among Sebacina spp. (Sebaci- naceae, Basidiomycota). Capronia sp. and Hymenoscyphus erica (Ascomycota) pre- dominated among the cultured fungi and formed intracellular hyphal coils in resynthesis experiments with salal. •We illustrate patterns of fungal diversity at the scale of individual roots and com- pare cloned and cultured fungi from each root. Indicating a systematic culturing detection bias, Sebacina DNAs predominated in 10 of the 15 roots yet Sebacina spp. never grew from cultures from the same roots or from among the > 200 ericoid mycorrhizal fungi previously cultured from different roots from the same site. -

Economic Cost of Invasive Non-Native Species on Great Britain F

The Economic Cost of Invasive Non-Native Species on Great Britain F. Williams, R. Eschen, A. Harris, D. Djeddour, C. Pratt, R.S. Shaw, S. Varia, J. Lamontagne-Godwin, S.E. Thomas, S.T. Murphy CAB/001/09 November 2010 www.cabi.org 1 KNOWLEDGE FOR LIFE The Economic Cost of Invasive Non-Native Species on Great Britain Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the input of many people from Great Britain and abroad. We thank all the people who have taken the time to respond to the questionnaire or to provide information over the phone or otherwise. Front Cover Photo – Courtesy of T. Renals Sponsors The Scottish Government Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, UK Government Department for the Economy and Transport, Welsh Assembly Government FE Williams, R Eschen, A Harris, DH Djeddour, CF Pratt, RS Shaw, S Varia, JD Lamontagne-Godwin, SE Thomas, ST Murphy CABI Head Office Nosworthy Way Wallingford OX10 8DE UK and CABI Europe - UK Bakeham Lane Egham Surrey TW20 9TY UK CABI Project No. VM10066 2 The Economic Cost of Invasive Non-Native Species on Great Britain Executive Summary The impact of Invasive Non-Native Species (INNS) can be manifold, ranging from loss of crops, damaged buildings, and additional production costs to the loss of livelihoods and ecosystem services. INNS are increasingly abundant in Great Britain and in Europe generally and their impact is rising. Hence, INNS are the subject of considerable concern in Great Britain, prompting the development of a Non-Native Species Strategy and the formation of the GB Non-Native Species Programme Board and Secretariat. -

The Parsnip That at One Time It Was Used As a Source of Sugar

Parsnip: Pastinaca sativa HISTORY “Parsnips have had their admirers for over 2,000 years. The emperor Tiberius accepted part of Germany's annual tribute in the form of a shipment of parsnips. So sweet is the parsnip that at one time it was used as a source of sugar. Parsnip wine has long been made in England, its high sugar levels contributing to a beverage somewhat like sherry.” (Botanica's Pocket Organic Gardening) CHARACTERISTICS The parsnip is a root crop very closely related to THE PARSNIP the carrot. They share the same basic shape, although parsnips are generally paler in color HERE are the main uses for the parsnip... and have a more distinct taste to them. They are planted in April or May, but must be left in the ground until the late fall or early winter in order 1 As mentioned above, the parsnip can be to expose them to consecutive below freezing made to have a very high sugar content by temperatures. This allows the starches to convert exposing it to frost, making it a perfect into sugar, giving the parsnip it unique, sweet candidate for not only wine, but also beer, syrup, nutty flavor. and marmalade's. 2 The roots can be baked, boiled, pureed, steamed, and fried. It can also be eaten raw in a salad. The parsnip is also described as an excellent additional to any soup, ragout, or stew. IN A PARSNIP In selecting the highest quality turnip, you first and foremost want to choose one that has been - Rich in calories exposed to frost. -

Journal of Agricultural Research Department of Agriculture

JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE VOL. V WASHINGTON, D. C, OCTOBER II, 1915 No. 2 PERENNIAL MYCELIUM IN SPECIES OF PERONOSPO- RACEAE RELATED TO PHYTOPHTHORA INFES- TANS By I. E. MELHUS, Pathologist, Cotton and Truck Disease Investigations, Bureau of Plant Industry INTRODUCTION Phytophthora infestans having been found to be perennial in the. Irish potato (Solanum tvherosum), the question naturally arose as to whether other species of Peronosporaceae survive the winter in the northern part of the United States in the mycelial stage. As shown in another paper (13),1 the mycelium in the mother tuber grows up the stem to the surface of the soil and causes an infection of the foliage which may result in an epidemic of late-blight. Very little is known about the perennial nature of the mycelium of Peronosporaceae. Only two species have been reported in America: Plasmopara pygmaea on Hepática acutiloba by Stewart (15) and Phytoph- thora cactorum on Panax quinquefolium by Rosenbaum (14). Six have been shown to be perennial in Europe: Peronospora schachtii on Beta vtUgaris and Peronospora dipsaci on Dipsacus follonum by Kühn (7, 8) ; Peronospora alsinearum on Stellaria media, Peronospora grisea on Veronica heder aefolia, Peronospora effusa on S pinada olerácea, and A triplex hor- tensis by Magnus (9); and Peronospora viiicola on Vitis vinifera by Istvanffi (5). Many of the hosts of this family are annuals, but some are biennials, or, like the Irish potato, are perennials. Where the host lives over the winter, it is interesting to know whether the mycelium of the fungus may also live over, especially where the infection has become systemic and the mycelium is present in the crown of the host plant.