LAING, John Stuart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministers Quarterly Returns 1 April 2012 to 30 June 2012

DEPARTMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT QUARTERLY INFORMATION 1 APRIL – 30 JUNE 2012 SECRETARY OF STATE ANDREW MITCHELL GIFTS GIVEN OVER £140 Date gift given To Gift Value (over £140) Rt Hon Andrew Mitchell MP, Secretary of State Nil return GIFTS RECEIVED OVER £140 Date gift From Gift Value Outcome received Rt Hon Andrew Mitchell MP, Secretary of State Nil return 1 OVERSEAS TRAVEL1 Rt Hon Andrew Mitchell MP, Secretary of State for International Development Date(s) of Destination Purpose of ‘Scheduled’ Number of Total cost trip trip ‘No 32 (The officials including travel, Royal) accompanying and Squadron’ Minister, where accommodation of or ‘other non-scheduled Minister only RAF’ or travel is used ‘Chartered’ or ‘Eurostar’ 03/04/2012 Belgium, World Bank Eurostar £462 – Brussels presidential 04/04/2012 candidates meeting with European Development Ministers. 10/04/2012 Brazil, To discuss Scheduled £7,837 – Brasilia and Rio +20 with 14/04/2012 Rio De high level Janeiro members of the Brazilian Government and take part in field visits. 19/04/2012 US, Attended the Scheduled £3,096 – Washington Spring 22/04/2012 Meetings of the World Bank and held a number of key bilateral discussions. 13/05/2012 Belgium, Meeting of Eurostar £572 – Brussels the European 14/05/2012 Foreign Affairs Council. 16/05/2012 Liberia, Met the Scheduled £8,355 – Monrovia President of 17/05/2012 Liberia to discuss issues of 1* indicates if accompanied by spouse/partner or other family member or friend. 2 mutual interest. 18/05/2012 US, Attended G8 Scheduled £4,578 – Washington Agriculture 19/05/2012 meetings. -

Web of Power

Media Briefing MAIN HEADING PARAGRAPH STYLE IS main head Web of power SUB TITLE PARAGRAPH STYLE IS main sub head The UK government and the energy- DATE PARAGRAPH STYLE IS date of document finance complex fuelling climate change March 2013 Research by the World Development Movement has Government figures embroiled in the nexus of money and revealed that one third of ministers in the UK government power fuelling climate change include William Hague, are linked to the finance and energy companies driving George Osborne, Michael Gove, Oliver Letwin, Vince Cable climate change. and even David Cameron himself. This energy-finance complex at the heart of government If we are to move away from a high carbon economy, is allowing fossil fuel companies to push the planet to the government must break this nexus and regulate the the brink of climate catastrophe, risking millions of lives, finance sector’s investment in fossil fuel energy. especially in the world’s poorest countries. SUBHEAD PARAGRAPH STYLE IS head A Introduction The world is approaching the point of no return in the Energy-finance complex in figures climate crisis. Unless emissions are massively reduced now, BODY PARAGRAPH STYLE IS body text Value of fossil fuel shares on the London Stock vast areas of the world will see increased drought, whole Exchange: £900 billion1 – higher than the GDP of the countries will be submerged and falling crop yields could whole of sub-Saharan Africa.2 mean millions dying of hunger. But finance is continuing to flow to multinational fossil fuel companies that are Top five UK banks’ underwrote £170 billion in bonds ploughing billions into new oil, gas and coal energy. -

Daily Report Thursday, 13 December 2018 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 13 December 2018 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 13 December 2018 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:34 P.M., 13 December 2018). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 6 Defence Science and ATTORNEY GENERAL 6 Technology Laboratory: Surveys 10 Criminal Proceedings: Disclosure of Information 6 Global Navigation Satellite Systems: Finance 11 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 6 Ministry of Defence: Institute for Statecraft 11 Global Navigation Satellite Systems: Finance 6 Russia: INF Treaty 11 CABINET OFFICE 6 Saudi Arabia: Joint Exercises 12 Brexit: Legal Opinion 6 Type 31 Frigates: Equipment 12 Civil Servants: Surveys 7 DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA AND SPORT 12 Cybercrime 7 Artificial Intelligence 12 Migrant Workers: EU Nationals 7 Charity Commission: Finance 13 Students: Suicide 8 Cultural Relations 13 Suicide 8 Department for Digital, CHURCH COMMISSIONERS 8 Culture, Media and Sport: EU Christians against Poverty 8 Law 13 DEFENCE 9 Gambling 14 Armed Forces: Death 9 Gambling: Advertising 14 Armed Forces: Radiation Gambling: Marketing 15 Exposure 9 Loneliness 16 Australia: Military Alliances 10 Lotteries 16 Christmas Island: Radiation Music: Education 17 Exposure 10 O2 17 Public Libraries: Children 18 Voluntary Work: Young People 18 Nitrogen Oxides: Pollution Writers 19 Control 30 EDUCATION 20 Trees 31 Academies: Finance -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 663 8 July 2019 No. 326 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 8 July 2019 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Penny Mordaunt, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

Middle East Peace: the Principles Behind the Process

Middle East Council MIDDLE EAST PEACE: THE PRINCIPLES BEHIND THE PROCESS Sir Alan Duncan MP A CMEC Palestine Program publication May 2016 FOREWORD The turbulence that has swept through the Middle East over the last five years continues – and in many cases the winds of change have brought only violence and humanitarian tragedy. Huge challenges remain. The region remains wracked by the competing dynamics of political Islam, tyranny and sectarian violence. But despite all this, the plight of the Palestinians remains unresolved as the central injustice of the region. Illegal settlements are, as each day passes, destroying the viability of a Palestine state, and with it all hope of a just and lasting peace for both Palestinians and Israelis. This is a risk that we, the US, Israel, and the Middle East region as a whole simply cannot afford to take. We in Great Britain must reenergise our efforts in pursuit of Palestine statehood and Middle East Peace . This excellent speech makes that point, and more. Sir Alan Duncan MP has a commendable track record of interest in the Palestine issue and I am delighted to see his powerful words published here. The Rt Hon Sir Nicholas Soames MP President Conservative Middle East Council Conservative Middle East Council MIDDLE EAST PEACE: THE PRINCIPLES BEHIND THE PROCESS INTRODUCTION This is a transcript of the speech delivered by The Rt Hon Sir Alan Duncan MP to RUSI on Tuesday 14th October 2014. May I start by expressing my gratitude to RUSI for providing me with a platform from which I can express my considered thoughts on an issue that has concerned – not to say, troubled – me for over thirty years. -

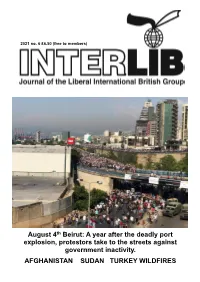

Interlib August 2021

2021 no. 6 £6.50 (free to members) August 4th Beirut: A year after the deadly port explosion, protestors take to the streets against government inactivity. AFGHANISTAN SUDAN TURKEY WILDFIRES EVENTS CONTENTS 17th - 20th September – Liberal Democrats Autumn Afghanistan enters a new phase in its tragedy, Conference. by George Cunningham page 3 8th-9th October – Scottish Liberal Democrats Virtual Afghanistan Refugees – LD4SoS page 4 Autumn Conference. The empire strikes back in Sudan, by Rebecca 9th-10th October – Democratiaid Rhyddfrydol Tinsley pages 5-7 Cymru/Welsh Liberal Democrats Virtual Autumn Conference Erdoğan is under fire, by Ahmet Kurt pages 89 International Abstracts page 9 For bookings & other information please contact the Treasurer below. Liberal Democrats for Seekers of Sanctuary page 10 NLC= National Liberal Club, Whitehall Place, London SW1A 2HE Reviews pages 11-12 Underground: Embankment Photographs: Waleed Ali Adam, Sales from the Crypt. Liberal International (British Group) Treasurer: Wendy Kyrle-Pope, 1 Brook Gardens, Barnes, London SW13 0LY email [email protected] Cover Photograph – Demonstration in Beirut against the government’s ineptitude in dealing with the aftermath of the Port explosion of 4th August 2020, when at least 217 people were killed and 7,000 injured. We hope to cover this in more detail in the next issue. Deadline for interLib 2021-07 - Conference issue We particularly welcome articles on international issues to be debated at the Liberal Democrats Autumn conference. May we have these by 31st August please, to [email protected] InterLib is published by the Liberal International (British Group). Views expressed therein are those of the authors and are not necessarily the views of LI(BG), LI or any of its constituent parties. -

40. Sayı 09.02.30.Indd

Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Pamukkale University Journal of Social Sciences Institute ISSN1308-2922 EISSN2147-6985 Article Info/Makale Bilgisi √Received/Geliş:23.04.2020 √Accepted/Kabul:24.05.2020 DOİ: 10.30794/pausbed.725855 Araştırma Makalesi/ Research Article Altınörs, G. (2020). "Devamlılık mı Kırılma mı? Brexit Sonrası Dönemde Birleşik Krallık-Türkiye İlişkilerinin Karşılaştırmalı Dış Politika Analizi" Pamukkale Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, sayı 40, Denizli, s. 285-302. DEVAMLILIK MI KIRILMA MI? BREXIT SONRASI DÖNEMDE BİRLEŞİK KRALLIK- TÜRKİYE İLİŞKİLERİNİN KARŞILAŞTIRMALI DIŞ POLİTİKA ANALİZİ Görkem ALTINÖRS* Özet Bu çalışmanın amacı Brexit’in Birleşik Krallık-Türkiye ilişkileri üzerindeki etkisini karşılaştırmalı dış politika analizi ile incelemektir. Bu bağlamda ikili ilişkilerin Brexit sonrasında bir devamlılığa mı yoksa kırılmaya mı işaret ettiği sorgulanmaktadır. Analiz için resmi demeçler veri olarak kullanılmıştır. Haziran 2016’da gerçekleşen Brexit referandumunun Birleşik Krallık dış politikası üzerinde çok büyük bir etkiye sahip olduğu ileri sürülebilir. Bu etkinin boyutları ve sınırlarını karşılaştırmalı olarak incelemek sürecin neler getireceğini anlamak açısından son derece önemlidir. Aynı dönemde Türkiye’nin dış politikasının da Suriye’deki iç savaş ve mülteci krizi gibi nedenlerle Amerika Birleşik Devletleri ve Avrupa Birliği ile çalkantılı bir süreç içerisinde olduğu görülmektedir. Bununla birlikte Temmuz 2016’da Türkiye’de başarısız bir darbe girişimi olmuştur. Bu süreç içerisinde gerçekleşen Birleşik Krallık-Türkiye yakınlaşması dikkate değerdir. Bu makalede bu yakınlaşma üç alt-başlık altında incelenmektedir: (1) Terörle mücadele, bölgesel güvenlik ve Suriye iç-savaşı, (2) Avrupa Birliği ve Kıbrıs ve (3) Ticaret ve Ekonomik İş-birliği. Bu çalışmanın ana argümanı ikili ilişkilerin Brexit sonrası dönemde bir kırılma göstermedikleri, aksine güçlenerek devam ettiği üzerine kuruludur. -

Human Rights and the Political Situation in Turkey 3

DEBATE PACK Number CDP 2017-0067 | 6 March 2017 Compiled by: Human rights and the Tim Robinson political situation in Subject specialist: Arabella Lang Turkey Contents 1. Background 2 Westminster Hall 2. Press Articles 4 3. PQs 6 Backbench Business 4. Other Parliamentary material 26 Thursday 9 March 2017 4.1 Urgent Questions and Statements 26 Debate initiated by Joan Ryan, David 4.2 Early Day Motions 29 Lammy, Tommy Sheppard and Sir Peter 5. Press releases 33 5.1 Gov.uk 33 Bottomley 5.2 European Union 38 6. Further reading 40 The proceedings of this debate can be viewed on Parliamentlive.tv The House of Commons Library prepares a briefing in hard copy and/or online for most non-legislative debates in the Chamber and Westminster Hall other than half-hour debates. Debate Packs are produced quickly after the announcement of parliamentary business. They are intended to provide a summary or overview of the issue being debated and identify relevant briefings and useful documents, including press and parliamentary material. More detailed briefing can be prepared for Members on request to the Library. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Number CDP 2017-0067, 6 March 2017 1. Background Turkey’s 16 April referendum is likely to pass, changing the constitution to give President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan significantly greater powers. Erdogan has been in power (first as Prime Minister and then as President) since 2002, and has made no secret of his ambition. The reforms have already been passed by Turkey’s parliament, with the support of the governing AK Party and the smaller nationalist MHP, but amid angry scenes. -

Labour's Last Fling on Constitutional Reform

| THE CONSTITUTION UNIT NEWSLETTER | ISSUE 43 | SEPTEMBER 2009 | MONITOR LABOUR’S LAST FLING ON CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM IN THIS ISSUE Gordon Brown’s bold plans for constitutional constitutional settlement …We will work with the reform continue to be dogged by bad luck and bad British people to deliver a radical programme of PARLIAMENT 2 - 3 judgement. The bad luck came in May, when the democratic and constitutional reform”. MPs’ expenses scandal engulfed Parliament and government and dominated the headlines for a Such rhetoric also defies political reality. There is EXECUTIVE 3 month. The bad judgement came in over-reacting a strict limit on what the government can deliver to the scandal, promising wide ranging reforms before the next election. The 2009-10 legislative which have nothing to do with the original mischief, session will be at most six months long. There PARTIES AND ELECTIONS 3-4 and which have limited hope of being delivered in is a risk that even the modest proposals in the the remainder of this Parliament. Constitutional Reform and Governance Bill will not pass. It was not introduced until 20 July, DEVOLUTION 4-5 The MPs’ expenses scandal broke on 8 May. As the day before the House rose for the summer the Daily Telegraph published fresh disclosures recess. After a year’s delay, the only significant day after day for the next 25 days public anger additions are Part 3 of the bill, with the next small HUMAN RIGHTS 5 mounted. It was not enough that the whole steps on Lords reform (see page 2); and Part 7, to issue of MPs’ allowances was already being strengthen the governance of the National Audit investigated by the Committee on Standards in Office. -

Question Time 8 March 2008

Question Time 8 March 2008 Questions 1. Tony Blair is to teach students at Yale University. On what subject will he teach? ( )Government & politics ( )Faith and globalisation ( )Media studies ( )International diplomacy 2. Former Foreign Secretary Lord Pym has died. To which political party did he belong? ( )Labour ( )Conservative ( )None ‐ he was an independent ( )Liberal Democrats 3. Who has secured the Republican Party's presidential nomination? ( )John McCain ( )Mike Huckarbee ( )Mike McCain ( )John Huckarbee 4. What policy aimed at encouraging healthier diets has been proposed by the LibDems? ( )Tax allowances for gym memberships ( )All able‐bodied adults should be required to undergo a fitness test ( )VAT on fruit juice and smoothies should ( )Free distribution of Jade Goody fitness be cut DVDs 5. The Conservatives have pledged that they will treble the tax on... ( )Saturated fats ( )Alcopops ( )Plastic bags ( )Windfarms 6. Who announced an intention to resign as First Minister and DUP leader? ( )Peter Robinson ( )Ian Paisley ( )Martin McGuinness ( )Bertie Aherne 7. David Cameron has commissioned a popular author to conduct a review into the treatment of the armed forces. Which author? ( )Andy McNab ( )Jeffrey Archer ( )Frederick Forsyth ( )J P Rowling 8. Who is to become the first Conservative MP to enter into a civil partnership? ( )Michael Gove ( )William Hague ( )Alan Duncan ( )Michael Portillo 9. Gordon Brown has urged British soldiers, sailors and airmen to... ( )smile more ( )wear their uniforms in public ( )publish their experiences on duty via ( )apply for postal votes before they are YouTube sent on active duty 10. Jacqui Smith, the Home Secretary, promised that 80 per cent of Britons would have something within nine years. -

Web of Power the UK Government and the Energy- Finance Complex Fuelling Climate Change March 2013

Media briefing Web of power The UK government and the energy- finance complex fuelling climate change March 2013 Research by the World Development Movement has Government figures embroiled in the nexus of money and revealed that one third of ministers in the UK government power fuelling climate change include William Hague, are linked to the finance and energy companies driving George Osborne, Michael Gove, Oliver Letwin, Vince Cable climate change. and even David Cameron himself. This energy-finance complex at the heart of government If we are to move away from a high carbon economy, is allowing fossil fuel companies to push the planet to the government must break this nexus and regulate the the brink of climate catastrophe, risking millions of lives, finance sector’s investment in fossil fuel energy. especially in the world’s poorest countries. Introduction The world is approaching the point of no return in the Energy-finance complex in figures climate crisis. Unless emissions are massively reduced now, Value of fossil fuel shares on the London Stock vast areas of the world will see increased drought, whole Exchange: £900 billion1 – higher than the GDP of the countries will be submerged and falling crop yields could whole of sub-Saharan Africa.2 mean millions dying of hunger. But finance is continuing to flow to multinational fossil fuel companies that are Top five UK banks’ underwrote £170 billion in bonds ploughing billions into new oil, gas and coal energy. and share issues for fossil fuel companies 2010-12 – more than 11 times the amount the UK contributed in The vested interests of big oil, gas and coal mining climate finance for developing countries.3 companies are in favour of the status quo. -

Download the Transcript

1 BRITAIN-2016/09/14 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION SAUL/ZILKHA ROOM GLOBAL BRITAIN: THE UNITED KINGDOM AFTER THE EU REFERENDUM Washington, D.C. Wednesday, September 14, 2016 PARTICIPANTS: Introduction and Moderator: FIONA HILL Senior Fellow and Director, Center on the United States and Europe The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: SIR ALAN DUNCAN MP Minister of State, Foreign and Commonwealth Office United Kingdom * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 2 BRITAIN-2016/09/14 P R O C E E D I N G S MS. HILL: Ladies and gentlemen, I'd just like to welcome you here today to the Brookings Institution. I'm Fiona Hill, Director of the Center on the United States and Europe. And it's a real pleasure to be able to introduce to you Sir Alan Duncan, who has actually literally just got off the plane from Buenos Aires in Argentina. I'm actually amazed that he's looking quite so fresh and put together. I don't know what I would be looking like if I just got off a plane from Argentina. And he's in town for a series of meetings all over the place with members of the administration. And we're just delighted we were able to entice him over to Brookings. Sir Alan is relatively new to his role as the Minister for Europe and he's going to today give us a brief presentation speech of an overview of the United Kingdom's current outlook on everything related to Europe, which of course has been somewhat fraught and contentious -- and I don't really have to stress that in this interjection, as well as the UK's relationship to the United States, which is obviously one of the features of his visit here, and some of the other global issues.