Trade Marks Opposition Decision (O/048/00)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archbishop: “Huge Diversity

July 2015 - Issue 8/15 News The Diocese of St Albans in Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, Luton & Barnet Archbishop: “Huge diversity. Enormous vigour. I’ve enjoyed everywhere.” Archbishop Justin’s three-day visit to St Albans waterways chaplaincy and hearing the accounts of Diocese was widely described as busy, including addicts helped by the Living Room’s care programmes by Archbishop Justin. He visited St Mary’s Church, for them and their families. Luton, the Mall and Luton Town Hall, Waterways In Stevenage, at the Love Herts youth event, Chaplaincy, St Albans Cathedral, St John’s Farley Hill, Archbishop Justin clearly enjoyed himself as well as Manshead Upper School, Bedford Prison, Bunyan giving the evening a serious dimension. “It was just Meeting Church, Shuttleworth College, Stevenage’s fun, yet very Jesus centred. A number of people came Love Herts Youth event, a business breakfast, the to faith in Christ during the course of the evening, Alban Pilgrimage and a discussion on world mission quite a significant number and that’s a wonderful with some of our link dioceses. After 15 engagements thing. That’s the church, doing it’s stuff, with young in three days, he was still smiling. people,” he said. Interviewed for BBC Three Counties Radio, he In his Presidential Address to Diocesan Synod, described his initial impression of the “huge diversity Bishop Alan said: “Taking him to so many places to and enormous vigour,” in the diocese. He was deeply see some of the work that is going on in every part impressed, during his visit to Luton, to see how issues of the diocese was both exciting and humbling. -

BBC Three Counties Radio - Make a Difference Awards 2020 Terms and Conditions

BBC Three Counties Radio - Make a Difference Awards 2020 Terms and Conditions 1. In order to nominate someone, you must be 18 or over (if you’re under 18 please ask your parent or guardian to nominate on your behalf) and a UK resident (including Channel Islands and the Isle of Man) and not be a BBC or BBC Group company employee, employee of any of its affiliates, close relative of any such employees or connected to the awards competition directly or through a close relative. 2. Any person who is a resident in Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire or Hertfordshire is eligible to be nominated, except BBC or BBC Group company employees, employees of any of its affiliates, close relatives of any such employees or connected to the award directly or through a close relative. Proof of age, identity and eligibility may be requested. 3. Nominations will be open at 0800 on Monday 29th June 2020 and close at 2359 on 21st August 2020. Entries received outside of these dates will not be considered. 4. Winners will be announced throughout the week commencing 21st September 2020. The BBC will also broadcast/publish the names (and ages for the Young Achiever Award) of the winners. 5. Nominations can be made via the link on the BBC Three Counties webpage www.bbc.co.uk/threecountiesradio. Listeners will be pointed towards the form through verbal, audio and online means including social media. Nominations can also be made by post to BBC 3 Counties Radio Court Drive Grove Park Dunstable LU5 4GP, using the downloadable form available online. -

BBC Radio Frequency Finder

BBC Radio Frequency Finder For transmitter details see: BBC RADIO 5 LIVE RADIOS 1, 2, 3 AND 4 FM FREQUENCIES Digital Multiplexes (98% stereo coverage, ~100% mono) FM Transmitters by Region Format: News, Sport and Talk; Based Manchester Area R1 R2 R3 R4 AM Transmitters by Region United Kingdom (BBC Mux) DABm 12B SOUTH AND SOUTH EAST ENGLAND FM and AM transmitter details are also included in the London and South East England AM 909 London & South East England 98.8 89.1 91.3 93.5 frequency-order lists. South East Kent AM 693 London area 98.5 88.8 91.0 93.2 East Sussex Coast AM 693 Purley & Coulsdon, London 98.0 88.4 90.6 92.8 National Brighton and Worthing area AM 693 Caterham, Surrey 99.3 89.7 91.9 94.1 South Hampshire and Wight AM 909 Leatherhead area, Surrey 99.3 89.7 91.9 94.1 Radios 1 to 4 are based in London. See tables at end for Bournemouth AM 909 West Surrey & NE Hampshire 97.7 88.1 90.3 92.5 details of BBC FM network. Stations broadcast 24 hours a day Devon, Cornwall and Dorset AM 693 Reading 99.4 89.8 92.0 94.2 except where stated otherwise. Exeter area AM 909 High Wycombe 99.6 90.0 92.2 94.4 West Cornwall AM 909 Newbury & West Berkshire 97.8 88.2 90.4 92.6 South Wales and West England AM 909 West Berkshire & East Wilts 98.4 88.9 91.1 93.3 ADIO BBC R 1 North Dyfed and SW Gwynedd AM 990 Basingstoke 99.7 90.1 92.3 94.5 Format: New Music and Contemporary Hit Music with Talk The Midlands AM 693 East Kent 99.5 90.0 92.4 94.4 United Kingdom (BBC Mux) DABs 12B Norfolk and Suffolk AM 693 Folkestone area 98.3 88.4 90.6 93.1 United Kingdom (see table) FM 97.1, 97.7 - 99.8 Yorkshire, NW England & Wales AM 909 Hastings 97.7 89.6 91.8 94.2 Satellite 0101/700, DTT 700, Cable 901 South Cumbria & N Lancashire AM 693 Bexhill 99.2 88.2 92.2 94.6 Airdate: 30/9/1967. -

For Further Information Packs Please Call BBC Three Counties Radio

For further Information packs please call Mid Beds District Council BBC Three Counties Radio Action Desk Debra Jeeves 01582 441111 Sports Development Officer Tel: (01525) 842220 Everyday sport is a campaign highlighting E-mail: [email protected] ways in which you can get active. If you are looking for ideas about activities in your local area the following list, although not South Beds District Council comprehensive, gives a good starting place. Lynda Challis Community Sports Development Officer National Contacts Tel: (01582) 474101 [email protected] Everyday Sport : http://www.everydaysport.com Tel : 0800 587 6000 Walking for Health Sport England : http://www.sportengland.org Active Places: National contact : http://www.whi.org.uk/ http://www.activeplaces.com/ East of England Contact A free to use website that holds the details of Countryside Agency thousands of sports and leisure facilities and 2nd Floor, City House allows people to log on and find local places 126 - 128 Hills Road where they can take part in sport and fitness Cambridge activities. CB2 1PT Tel: 01223 354462 County contact Pete Hardy Leisure Centres Bedfordshire Active Sports Manager Tel: (01234) 316068 Mobile: 07796 990989 Dunstable Leisure Centre E-mail: [email protected] 01582 608107 Website: www.bedsactivesports.com Flitwick Leisure Centre 01525 717744 Local councils Houghton Regis Leisure Centre Bedford Borough Council 01582 866141 Richard Tapley Sports Development Officer Lea Manor Recreation Centre Tel: (01234) 221753 01582 599888 E-mail: [email protected] Putteridge Recreation Centre 01582 731664 Luton Borough Council Mark Southam Tiddenfoot Leisure Centre 01525 375765 Sports Development Manager Tel: (01582) 400272 E-mail: [email protected] . -

BBC Radio Post-1967

1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Operated by BBC Radio 1 BBC Radio 1 Dance BBC Radio 1 relax BBC 1Xtra BBC Radio 1Xtra BBC Radio 2 BBC Radio 3 National BBC Radio 4 BBC Radio BBC 7 BBC Radio 7 BBC Radio 4 Extra BBC Radio 5 BBC Radio 5 Live BBC Radio Five Live BBC Radio 5 Live BBC Radio Five Live Sports Extra BBC Radio 5 Live Sports Extra BBC 6 Music BBC Radio 6 Music BBC Asian Network BBC World Service International BBC Radio Cymru BBC Radio Cymru Mwy BBC Radio Cymru 2 Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Cymru Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Radio Wales BBC Radio Gwent BBC Radio Wales Blaenau Gwent, Caerphilly, Monmouthshire, Newport & Torfaen BBC Radio Deeside BBC Radio Clwyd Denbighshire, Flintshire & Wrexham BBC Radio Ulster BBC Radio Foyle County Derry BBC Northern Ireland BBC Radio Ulster Northern Ireland BBC Radio na Gaidhealtachd BBC Radio nan Gàidheal BBC Radio nan Eilean Scotland BBC Radio Scotland BBC Scotland BBC Radio Orkney Orkney BBC Radio Shetland Shetland BBC Essex Essex BBC Radio Cambridgeshire Cambridgeshire BBC Radio Norfolk Norfolk BBC East BBC Radio Northampton BBC Northampton BBC Radio Northampton Northamptonshire BBC Radio Suffolk Suffolk BBC Radio Bedfordshire BBC Three Counties Radio Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire & North Buckinghamshire BBC Radio Derby Derbyshire (excl. -

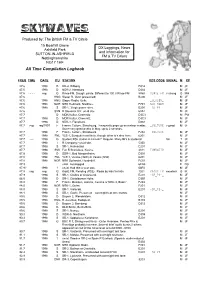

All Time Compilation Logbook by Date/Time

SKYWAVES Produced by: The British FM & TV Circle 15 Boarhill Grove DX Loggings, News Ashfield Park and Information for SUTTON-IN-ASHFIELD FM & TV DXers Nottinghamshire NG17 1HF All Time Compilation Logbook FREQ TIME DATE ITU STATION RDS CODE SIGNAL M RP 87.6 1998 D BR-4, Dillberg. D314 M JF 87.6 1998 D NDR-2, Hamburg. D382 M JF 87.6 - - - - reg G Rinse FM, Slough. pirate. Different to 100.3 Rinse FM 8760 RINSE_FM v strong GMH 87.6 HNG Slager R, Gyor (presumed) B206 M JF 87.6 1998 HNG Slager Radio, Gyšr. _SLAGER_ MJF 87.6 1998 NOR NRK Hedmark, Nordhue. F701 NRK_HEDM MJF 87.6 1998 S SR-1, 3 high power sites. E201 -SR_P1-_ MJF 87.6 SVN R Slovenia 202, un-id site. 63A2 M JF 87.7 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz D3C3 M PW 87.7 1998 D MDR Kultur, Chemnitz. D3C3 M JF 87.7 1998 D NDR-4, Flensburg. D384 M JF 87.7 reg reg/1997 F France Culture, Strasbourg. Frequently pops up on meteor scatter. _CULTURE v good M JF Some very good peaks in May, up to 2 seconds. 87.7 1998 F France Culture, Strasbourg. F202 _CULTURE MJF 87.7 1998 FNL YLE-1, Eurajoki most likely, though other txÕs also here. 6201 M JF 87.7 ---- 1998 G Student RSL station in Lincoln? Regular. Many ID's & students! fair T JF 87.7 1998 I R Company? un-id site. 5350 M JF 87.7 1998 S SR-1, Halmastad. E201 M JF 87.7 1998 SVK Fun R Bratislava, Kosice. -

Picture Courtesy of Megan F Webb Photography St LUKE’S, STOKE HAMMOND

SH NEWS INSIDE THIS EDITION: SEPTEMBER 2018 Issue 9 PARISH COUNCIL NEWS G.O.W. (not a spelling mistake – it’s the turn of the Grumpy Old Woman) MAVIS’S QUIZ EVERYTHING BUT THE MOO SPOTLIGHT ON ‘LOUISA HARRIS’ READERS LETTERS ARCHAEOLOGICAL OPEN DAY BOOK REVIEW & MUCH MORE www.stokehammondpc.com Picture Courtesy of Megan F Webb Photography St LUKE’S, STOKE HAMMOND Rector: Revd John Waller 01525 261062 September 2nd 11.00 United Service at Methodist Church September 9th 09.00 Holy Communion – Revd Norman Thorp September 16th 09.00 Holy Communion – Revd John Waller September 23rd 09.00 Morning Worship – Lay Leader September 30th 11.00 Holy Communion at Great Brickhill Revd John Waller PLEASE ALSO NOTE THE FOLLOWING DATES FOR COMMUNITY BREAKFASTS AT THE COMMUNITY CENTRE, BRAGENHAM SIDE. Saturday 22nd September 08.30 – 10.30 (Last Orders) Saturday 13th October 08.30 – 10.30 (Last Orders) Church Wardens: Diane Webber 01525-270409 and Harry Davies 01234-822780 METHODIST SERVICES Minister: Revd Donna Broadbent-Kelly 01525 240589 September 2nd 11.00 Harvest Festival – Mr John Shaw September 9th Local Arrangement September 16th Local Arrangement September 23rd Local Arrangement September 30th Local Arrangement Coffee Mornings Wednesdays at 10.30 - 11.30 (contact 01525-270287) PARISH COUNCIL NEWS In a similar vain to July and with there being no PC Meeting in August, Parish News for the last month is again rather short on supply. The Bypass resurfacing works are now well underway with the Northbound route closed for its entire length, and whilst the traffic through the village has increased, a lot of people are pleasantly surprised that it is not as heavy as they had feared it might be. -

Cycling for the Common Good the Friend Independent Quaker Journalism Since 1843

10 August 2018 £2.00 theDISCOVER THE CONTEMPORARYFriend QUAKER WAY Cycling for the common good the Friend INDEPENDENT QUAKER JOURNALISM SINCE 1843 Contents VOL 176 NO 32 3 Thought for the Week: Cyclists arrrive Beauty and the predator Derek Guiton 4-5 News 6 Peace Hub Peter Doubtfire 7 Something to celebrate: Berkhamsted Marjorie Lazaro 8-9 Letters Photo: Isaac Peat. 10-11 Quakers, crime and the United Nations THE QUAKER CYCLIsts giving Marian Liebmann witness to their concern about ‘the 12 What is a friend? dismantling of the welfare state’ arrived at 10 Downing Street on 3 Margaret Roy August. 13 The heartbeat of time Those taking part in the ‘Ride Bernard Coote for Equality and the Common Good’ successfully completed the 14-15 Moscow diary: Marjorie Farquarson 360-mile journey, carrying their Alastair Hulbert Declaration, together with the stories on postcards of some of 16 Poem: those affected by welfare cuts. In Quaker Meeting The Ride for the Common Lesley Morris Good began at Swarthmoor Hall in Cumbria on 22 July. 17 Friends & Meetings Cover image: Photo: Jenny Tyldesley. See page 2 The Friend Subscriptions Advertising Editorial UK £88 per year by all payment Advertisement manager: Editor: types including annual direct debit; George Penaluna Ian Kirk-Smith monthly payment by direct debit [email protected] £7.40; online only £71 per year. Articles, images, correspondence For details of other rates, Tel 01535 630230 should be emailed to contact Penny Dunn on 54a Main Street, Cononley [email protected] 020 7663 1178 or [email protected] Keighley BD20 8LL or sent to the address below. -

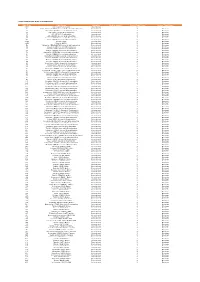

Codes Used in D&M

CODES USED IN D&M - MCPS A DISTRIBUTIONS D&M Code D&M Name Category Further details Source Type Code Source Type Name Z98 UK/Ireland Commercial International 2 20 South African (SAMRO) General & Broadcasting (TV only) International 3 Overseas 21 Australian (APRA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 36 USA (BMI) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 38 USA (SESAC) Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 39 USA (ASCAP) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 47 Japanese (JASRAC) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 48 Israeli (ACUM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 048M Norway (NCB) International 3 Overseas 049M Algeria (ONDA) International 3 Overseas 58 Bulgarian (MUSICAUTOR) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 62 Russian (RAO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 74 Austrian (AKM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 75 Belgian (SABAM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 79 Hungarian (ARTISJUS) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 80 Danish (KODA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 81 Netherlands (BUMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 83 Finnish (TEOSTO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 84 French (SACEM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 85 German (GEMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 86 Hong Kong (CASH) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 87 Italian (SIAE) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 88 Mexican (SACM) General & Broadcasting -

Business Wire Catalog

UK/Ireland Media Distribution to key consumer and general media with coverage of newspapers, television, radio, news agencies, news portals and Web sites via PA Media, the national news agency of the UK and Ireland. UK/Ireland Media Asian Leader Barrow Advertiser Black Country Bugle UK/Ireland Media Asian Voice Barry and District News Blackburn Citizen Newspapers Associated Newspapers Basildon Recorder Blackpool and Fylde Citizen A & N Media Associated Newspapers Limited Basildon Yellow Advertiser Blackpool Reporter Aberdeen Citizen Atherstone Herald Basingstoke Extra Blairgowrie Advertiser Aberdeen Evening Express Athlone Voice Basingstoke Gazette Blythe and Forsbrook Times Abergavenny Chronicle Australian Times Basingstoke Observer Bo'ness Journal Abingdon Herald Avon Advertiser - Ringwood, Bath Chronicle Bognor Regis Guardian Accrington Observer Verwood & Fordingbridge Batley & Birstall News Bognor Regis Observer Addlestone and Byfleet Review Avon Advertiser - Salisbury & Battle Observer Bolsover Advertiser Aintree & Maghull Champion Amesbury Beaconsfield Advertiser Bolton Journal Airdrie and Coatbridge Avon Advertiser - Wimborne & Bearsden, Milngavie & Glasgow Bootle Times Advertiser Ferndown West Extra Border Telegraph Alcester Chronicle Ayr Advertiser Bebington and Bromborough Bordon Herald Aldershot News & Mail Ayrshire Post News Bordon Post Alfreton Chad Bala - Y Cyfnod Beccles and Bungay Journal Borehamwood and Elstree Times Alloa and Hillfoots Advertiser Ballycastle Chronicle Bedford Times and Citizen Boston Standard Alsager -

Aylesbury Vale District Council Emergency Plan

Aylesbury Vale District Council Emergency Plan Version Date 2.1 November 2011 2.2 18/06/12 Author: People and Payroll Division, The Gateway, Gatehouse Road, Aylesbury, 01296 585158; [email protected] Uncontrolled Version – no personal data 1 Version 2.2 June 2012 AYLESBURY VALE DISTRICT EMERGENCY PLAN Aylesbury Vale District 2 Version 2.2 June 2012 AYLESBURY VALE DISTRICT EMERGENCY PLAN INITIAL INCIDENT NOTIFICATION Date Time Who has rung you Their mobile and landline numbers About the Incident (Information to be passed on to Response Managers and LALOs) Where is it? Grid reference and Page No of A-Z What has Happened Details of any hazards arising out of the incident and precautions? What Action is Required by AVDC ? Time of Incident How long is the emergency How many people have been expected to last? displaced? Details of Displaced people? (age/disability etc.) loss of life etc. Where is the Rendezvous Point for LALOS? Safe Route Access to Location Who is the Incident Controller? Who have I contacted? Time Alerted: others Name (block capitals): Time called out to incident (if applicable): Date: Time spent on response (hours/minutes): District Co-ordinating Officer’s signature: 3 Version 2.2 June 2012 AYLESBURY VALE DISTRICT EMERGENCY PLAN Simplified Call Out Process List of key Contacts For full list see Section 2 of the Emergency Plan Role Work Mobile Home Resilience Officer 585158 David Thomas Substitute/Support 585005 RO –Kay Aitken Teresa Lane 585006 Andrew Grant 585002 Jon McGinty 585252 Matt Partridge 585181 -

Three Counties Radio Every Weekday Afternoon from 2 to 4.30Pm for Big Name Guests, Expert Advice and Stories from Where You Live in Beds, Herts and Bucks

Listen to Lorna Milton on BBC Three Counties Radio every weekday afternoon from 2 to 4.30pm for big name guests, expert advice and stories from where you live in Beds, Herts and Bucks. For comprehensive information and advice on all aspects of living with Parkinson's, the support available from the Parkinson’s Disease Society and how you can get involved, please visit our website at - www.parkinsons.org.uk For advice and information on local medical and support services and benefits, for people with Parkinson's and their families in the Three Counties area, please contact your local Parkinson's Disease Society Information and Support Worker: Area Contact Tel. & Email address Bedfordshire Jackie Kennedy 0844 225 3795 [email protected] South and Mid- Anita Browne 0844 225 3675 Buckinghamshire [email protected] Milton Keynes & North Denise Wilcox 0844 225 3773 Buckinghamshire [email protected] West Hertfordshire Tracey Tucker 0844 225 3779 [email protected] North East Vicky Symonds 0844 225 3775 Hertfordshire [email protected] Northamptonshire Kathy Carmichael 0844 225 3741 [email protected] Details of Information and Support Workers outside of these areas are available from the Society’s website: www.parkinsons.org.uk Local Parkinson's Disease Society Branches and Groups: Bedford – meet at Goldington Social Centre, 10 Barkers Lane, Bedford on the first Friday of the month at 7.30pm (except in January). Contact Bill Brady on [email protected] Leighton Buzzard - meet on the third Monday of the month at St George's Court from 2.30pm to 4.30pm.